Activism

Standing up to the Social-Justice Mobs Within the Jewish Community

The white Jewish leaders who attended were told in advance that they were expected to come and listen—to be seen and not heard.

A black and Jewish diversity officer, April Powers, recently resigned from her post at the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), after a mob descended on her for not mentioning Islamophobia in a statement she’d issued about the rise in anti-Semitism. “I neglected to address the rise in Islamophobia, and deeply regret that omission,” Powers said. “As someone who is vehemently against Islamophobia and hate speech of any kind, I understand that intention is not impact and I am sorry.”

Even just a few years ago, such a cancellation would have seemed bizarre and outrageous—especially the suggestion that the morality of one’s actions may be judged according to their “impact,” as subjectively assessed by third-party activists. Neither would we have understood why decrying one form of bigotry without mentioning another is problematic. We have just witnessed a series of news cycles in which we have all been invited to decry bigotry against blacks, Asians, members of the LGBT community, and other groups. Was each of these population-specific calls to action also problematic?

— scbwi (@scbwi) June 27, 2021

The first time I remember hearing the term “woke” was at a gathering of black and Jewish activists in New York City in the fall of 2016. I was then leading a Jewish organization that builds bridges to other communities and advocates for values that would now fall under the label of “social justice.”

The term Black Lives Matter was then relatively new, having become nationally popularized following the 2014 killing of Michael Brown at the hands of a local police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. In early 2016, an offshoot of this loosely-knit movement, calling itself the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), issued a platform that, among other things, denounced Israel for “the genocide committed against the Palestinian people,” and labeled Israel “an apartheid state.” Jewish leaders accused the authors of anti-Semitism, while M4BL activists accused Jewish leaders of using the issue to “decenter” the black experience—a charge I would hear over and over again. The goal of my organization was to make common cause. But this kind of extreme rhetoric made that task more difficult.

When a group of black Jews organized that fall 2016 meeting with Black Lives Matter activists in New York, in an effort to repair the black-Jewish rift, I jumped at the opportunity. I was initially denied entry because of an article I’d written that was critical of intersectionality (the theory that requires all social-justice dialogue to begin from the premise that the worth of a person’s perspective may be evaluated through a mechanical analysis of their intersecting markers of identity). But after lengthy discussions with a proxy for one of the organizers (in which I was told I needed to “do the work”) and my issuing a mea culpa for my published article, I was allowed in.

This was the first of several compromises I made, through which I betrayed my liberal values in a bid to appease people or groups with anti-liberal agendas. As I learned, it was never enough. And I now regret going down this path.

The white Jewish leaders who attended were told in advance that they were expected to come and listen—to be seen and not heard. There would be a time to ask questions in small groups, but we were not allowed to challenge anything we heard during the main discussion. The speakers were presented as authentic voices of marginalized communities. What we were hearing was revealed truth.

There were many firsts that evening. It was the first time I heard black Jews say white Jews had benefited from white supremacy, and so needed to “shed” their “whiteness.” I came to later understand that, like other privileged groups, such as Asian Americans, we were guilty of “white adjacency.” The path to forgiveness could only begin (though of course would not end) with an acknowledgement of our complicity in white supremacy, a confession that also would serve to indicate our acceptance of intersectionality and related doctrines.

Needless to say, I have no tolerance for actual white supremacists—who typically have no less contempt for Jews than for other minority groups. For the speakers lecturing us, however, white supremacy had a far broader meaning. The term described the entire fundamental organizing principle of America itself, and indeed all Western countries. This meaning of the term is now commonly at play in social-justice parlance, but at the time, it was new and confusing to many of us.

But I didn’t dare ask questions, let alone challenge the dubious claims I was hearing. I knew, on some level, that this was part of a power play within the Jewish community, an exercise meant to make people like me feel silent, humiliated, and powerless. The generous interpretation of this spectacle is that it was an educational interlude: We were being made to feel like blacks often feel in the midst of whites. But it was also made clear that this meeting wasn’t a one-off consciousness-raising session: Our role moving forward, we were told, was to acknowledge our own guilt, “make space” for non-whites, and “lift up” black voices. This was not civil rights as I knew it, or any other social justice movement predicated on a spirit of cooperation and equality. The room was divided between those being shamed and those doing the shaming.

At the end of the meeting, one of the organizers drew the black participants into a circle. She preached—that is the right word, I think—“I was blind, but now I am woke.” The participants repeated the chant, and proclaimed “Amen.” I have always been moved by the unique style of gospels, hymns, and professions of faith that are associated with the black church-going tradition, as these give beautiful expression to congregants’ deep and authentic connection to the divine spirit. But what was on display here was something different. The event organizers were using the language of religion, and exhibiting great fervor in their devotion. But this was plainly political. And the aim wasn’t to glorify God or the human spirit, but to denigrate a portion of the human population.

The dogma I was being asked to internalize has its own internal logic, as with established religion. It has created its own vocabulary, its own historical myths, and conception of morality. Its acolytes do not see themselves as pursuing a mere social movement aimed at ending a particular problem (racism), but rather vanguard elements espousing a totalizing worldview—a replacement theology—that explains the problem of evil in the world while aiming to topple the demonic (white supremacist) power structure that stands in their way.

As a Jew, I already have a religion. And if I were to choose another, this one wouldn’t be it.

I grew up in Columbus, Ohio to an Iraqi Jewish mother, who came to the United States in 1963, and a US-born, third-generation father of European Jewish descent. When I was three, my grandmother immigrated from Baghdad and moved in with us. Three years later, my grandmother’s sister and her 14-year-old son moved in with us from Iraq and took my brother’s bedroom for three years. The house was bustling with high-pitched laughter and arguments laced in colorful Arabic swear words and a screeching parrot named Bibi. My father, who spoke no Arabic, often took refuge in the bedroom, while I spoke to my grandmother and great aunt in a Jewish dialect of Arabic. (It always struck me as odd and not a little exclusionary that American Jews acted as if all Judaism were European—or Ashkanazic—in origin. Why was corned beef a “Jewish food,” I wondered, but not kubbah, the dumplings eaten by Iraqi Jews?) Every Sunday morning, the smell of searing cumin woke me up as my grandmother made kitchry, the Jewish rice and red lentil delicacy. I appreciate the dish now more than I did then.

When I first heard that American Jews were supposed to divide themselves between white Jews and “Jews of color” (including Mizrahi Jews—once called “Oriental Jews”—like me), I was puzzled: It never occurred to me that I should see myself as a Jew “of color,” in part because I had never experienced racism.

Raised by an immigrant parent who practically worshipped the United States, I embraced the narrative of an America that is constantly striving to live up to its ideals. The America I grew up in was not racist, but certainly had racism in it. I still hold by that narrative today. And the woke claim that America is white supremacist strikes me as both wrong and dangerous: For all its faults, America is the most successful experiment in pluralism in world history. Immigrants with black and brown skin still flock here, and my eccentric family was proof of the opportunity that lies within.

Five years after that 2016 meeting in New York, it is remarkable to see how the woke faith has spread into mainstream discourse and institutions. Its appeal grows out of the profound collective guilt of privileged white people. And it is based on a grain of truth: It is absolutely true that the color-blind promise of America truly has gone unfulfilled for many Americans, blacks especially. The Jewish community, in particular, has not been nearly as inclusive of Jews of color as we should be. We have our own cheshbon hanefesh—an accounting of the soul—to make. One black Jew told me, much to my horror, about her experience in synagogue when an older lady presumed she was “the help.” Sadly, this isn’t uncommon.

But it is one thing to goad people into doing better, and another thing to base a political movement on their sinfulness. What’s more, those who’ve pushed back on this toxic political trend are now routinely branded as racist, while those who seek to ingratiate themselves with activists will make every imaginable rhetorical concession as a means to earn approval and forgiveness. Neither is helpful.

There is a tendency in progressive circles to roll one’s eyes at complaints about “cancel culture” or radicalized wokeness, on the suspicion that these are just FOX News talking points or veiled manifestations of “white fragility.” I remember a very liberal colleague of mine saying sometime in the early 2000s, “let’s not give the white-privilege crowd” any attention, on the assumption that the movement would run its course if we just ignored it. But the campus activists of that era are now managers, CEOs, and elected politicians. Even if they still comprise the minority in most organizations, no one wants to open themselves up to ideological accusations if they dissent from their puritanical social-justice agenda.

Much of the US Jewish establishment has now been swept up in this movement. In many cases, Jewish organizations are short-circuiting their usual deliberations (a hallmark of Jewish civic life) so they can go all in on whatever message happens to be trending on woke social media. They also have adapted the whole hyperbolic lexicon of wokedom—by which disagreement becomes “harm” or even “violence.” All three non-orthodox denominations—Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist—have enunciated their support for the idea of critical race theory. No one bothered to ask rank and file members if they believe America today is a white supremacist state. Perhaps the leaders of these movements are scared that, if they did ask, the answers would be off-message.

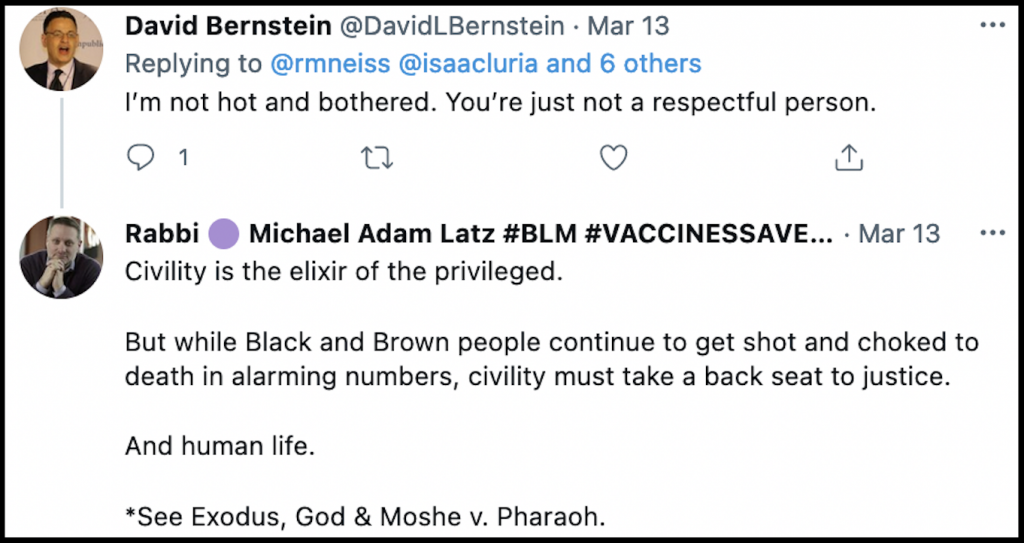

In the name of racial justice and “Jewish values,” Jews, even rabbis, now see fit to bully other Jews on social media. These “kindly inquisitors” (as Jonathan Rauch once called them) shame and ostracize others for daring to think differently, denouncing supposed wrongthink as an impediment to unity. The activist Rabbi Michael Adam Latz informs me that “Civility is the elixir of the privileged,” and that “while Black and Brown people continue to get shot and choked to death in alarming numbers, civility must take a back seat to justice” (adding, by way of citation, “See Exodus, God & Moshe v. Pharaoh”).

Before I stepped away from my job in the Jewish world, I was present in a meeting with a former colleague—let’s call him Jeremy—who’d unknowingly stepped on a landmine while inquiring about the number of Jews of color in the United States. Ira Sheskin and Arnold Dashefsky, demographers with decades of experience studying Jewish populations, had written an article for eJewish Philanthropy stating that the numbers of Jews of Color reported in a recent survey was likely exaggerated. Their research indicated that the actual figure is about six percent to seven percent, instead of the 12 percent to 15 percent estimate elsewhere cited. There was an immediate outcry over what was perceived as a political attack on non-white Jews. The head of the Reform movement, Rabbi Rick Jacobs, co-wrote a piece accusing the authors of “white intellectualism” and erasure.

I was stunned that any respected Jewish leader would use “intellectualism” as a pejorative, and certainly never knew intellectualism had a color. And yet Jacobs explicitly argued that the dictates of social justice are such that off-message facts must take a back seat to on-message feelings. “Such arguments seek to separate scholarship from the lived experiences and accompanying emotions of Jews of Color,” he argued. “By focusing solely on statistics, detractors neither examine nor even consider why, exactly, Jews of Color are not visible in our communities”

When Jeremy asked about the actual data, one of the higher-status Jewish leaders in his group angrily called him out. “We are not discussing this,” he insisted. No one—including me, I am ashamed to say—came to his defense.

Later that week, I heard from another meeting participant that several people accused Jeremy of making “inappropriate” and “racist” remarks—by which they meant his reference to the numbers of black Jews. I continued to stay mute, fearing that speaking up would compromise my positioning in the group. I called up Jeremy later that day. “Sorry you had to go through that,” I said. But we both knew that being “sorry” doesn’t mean much if you don’t say anything publicly. This was just one of numerous failures on my part, most of which I cannot speak about, to stand up for friends and uphold the liberal values that I hold dear.

Several months ago, I left my position heading a national Jewish advocacy organization. And I have some cheshbon hanefesh of my own to do—not over my supposed complicity in our supposed white supremacist state, but over my silence in the face of bullying, and for my personal cowardice. When I left the job, I decided to write a piece arguing that Jewish organizations should carefully think through tough questions on race and racism before signing on to cultish dogmas. The movement, I feared, “can have a corrupting influence on Jewish organizational values.”

The responses on progressive Jewish Twitter, many of which came from former friends, was fast and furious. You would have thought I’d denounced Judaism itself. But rather than shut me down, the experience only confirmed that I’d made the right decision, as this mob was acting out the very phenomenon I’d described. I spoke to several funders, and secured support to create the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values, dedicated to fighting for liberalism and against cancel culture in the Jewish world. Our efforts have included the creation of a “Jewish Harper’s Letter,” signed by leading thinkers such as Steven Pinker, Jonathan Haidt, Lee Jussim, James Kirchik, Bethany Mandel, Pamela Paresky, Abigail Shrier, Christina Hoff Sommers, Bret Stephens, Cathy Young, Bari Weiss, and Nadine Strossen. Our goal is to amplify the voices of independent-minded liberal Jews who are willing to stand up for liberalism.

In May, the Pew Research Center issued a new Jewish demographic study, in which 92 percent of US Jewish respondents described themselves as white. The eight percent non-white figure—up two points in the past eight years—is, according to aforementioned demographer Ira Sheskin, “about what we would expect given the 6% [figure observed] seven years ago.” But to this day, not one of his detractors has apologized for the unhinged attacks he and his co-author endured last year merely for reporting objective facts.

My apologies to Ira, Jeremy, and all the other Jews who’ve been attacked for not reciting the canned lines placed in front of them by ideological enforcers in our community. You deserved better from your fellow Jews, including from me. And in the years to come, I’ll be doing my best to—as the expression goes—“do the work” required to undo, or at least oppose, the damage I have witnessed.

David Bernstein is founder of the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values. You can find him on Twitter at @DavidLBernstein. Parts of this article were adapted from an earlier piece published in the Jewish Journal.

More from the author.