Culture Wars

The Limitations of Black Conservative Thought

Perhaps if black conservatives offered a more nuanced “vision” of the respective roles of individuals and governments in addressing racial inequality, the black community would be less receptive to the anti-racist narrative that conservatives so vehemently denounce.

I.

Can we choose to be optimistic or pessimistic about our future prospects? Can we choose our appetite for risk or our attitude toward conformity? Can we choose to bolster our self-esteem if we know that low self-esteem is causing us grief?

Few of us believe we are entirely free to conduct a sober, sophisticated cost-benefit analysis every time we face an important decision in life, whether it’s how much to study for a final exam, when to end a long-term relationship, or if we should order one last drink before the bar closes. Similarly, few of us believe we live in an entirely deterministic world in which we are free only to rationalize our behavior after the fact.

So, how free are we? Science provides us with plenty of empirical evidence to suggest we are not as free as our most exuberant defenders of human freedom assume, but it will likely be a few more decades, if not longer, before neuroscientists, endocrinologists, evolutionary biologists, sociologists, psychologists, and scientists of as-yet-unnamed disciplines identify precisely where we belong on the spectrum between perfect self-mastery and complete subordination to forces outside of our control.

The existence of this gray zone—a vast and largely uncharted terrain—goes a long way toward explaining why partisans of all persuasions are convinced that the facts in any particular political debate are overwhelmingly on their side, and that their opponents are confused or self-interested ideologues. It is into this zone of uncertainty that black conservatives and progressives deployed their conceptual armies in the 1960s, and it is where they have been engaging in a form of trench warfare ever since. Black conservatives insist on the power and importance of self-mastery. Black progressives argue that social and economic forces are oppressive and often insurmountable. Artillery shells—sometimes loaded with empirical evidence, but more often packed with anecdotal evidence, strawmen, false dichotomies, and personal insults—are lobbed back and forth.

Why do racial disparities persist in our country? This is the key question that divides black intellectuals. Why do racial disparities in income, wealth, education, incarceration, healthcare, and homeownership persist, despite the fact that legal discrimination ended in the mid-1960s? Candidates for explanatory pre-eminence abound: current racism, past racism (the legacy of slavery and segregation), structural racism, institutional racism, implicit bias, excessive government intervention, insufficient government intervention, structural changes to our economy (deindustrialization, globalization, digitization, etc.), individual psychology, and black culture.

Rather than attempt to clarify these contested terms, I want to explore why black conservatives and progressives rank these explanatory factors so differently. Blacks of all political persuasions would agree that we are not yet free to alter our genetic inheritance, and that genetic differences do not explain current racial inequalities. Where conservatives and progressives disagree—without always recognizing the fundamental point of departure—is on the extent to which we can choose to alter, embrace, reform, or disown our cultural inheritance.

I intend to explore these differences by focusing on the two main strands of contemporary black conservative thought—the victimhood hypothesis and the cultural hypothesis, represented here by conservative writers Shelby Steele and Thomas Sowell, respectively. Most conservatives today would probably object to such a neat division. Nevertheless, this narrowing of the scope of this essay is justified, I believe. Not all simplifications are over-simplifications, and my hope is that this device will clarify more than it obscures.

To the great frustration of black conservatives, progressive black thought has dominated the intellectual and cultural landscape over the last few years (decades, many would complain). As a result, conservatives have spent a great deal of energy criticizing progressive intellectuals such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ibram X. Kendi, and Isabel Wilkerson, rather than engaging in the kind of self-criticism that would help them develop their own arguments. Like most black conservatives, I am not convinced that racism/anti-racism is the best framework for advancing racial equality, that “caste” is the best metaphor for describing race relations in our country, or that movements to “defund” the police will decrease crime in majority black neighborhoods. But what do black conservatives offer other than criticism of progressive ideas?

II.

Do we choose the level of parental investment we receive as young children? Do we choose the rate of violent crime in our neighborhoods as adolescents? Do we choose how prestige and status is distributed in our communities as adults?

Let us assume for the moment that adult members of our species can in fact exercise their wills freely. The question we must now ask ourselves is the age at which we expect this admirable self-mastery to kick in. Developmental psychologists have taught us that children develop in stages. At two months old, most infants can smile and make gurgling sounds. By two years of age, most toddlers can speak in three-and-four-word sentences and have developed a knack for acting defiantly. By five, most kids can distinguish between what is real and what belongs to the world of make-believe, and they can follow the rules of a complicated game right up until the point when they decide a different set of rules would suit them better. Empathy, we know, takes quite a bit longer to develop, and being able to consistently see things from another person’s point of view is a cognitive skill that few of us ever perfect. Now, in this rough sketch of human development, where would we place the emergence of self-mastery, which is what we would need to possess to exercise our wills freely?

Most people would probably pinpoint the age of self-mastery—the age of choice and individual responsibility—somewhere between 18, when we can vote and serve in the military, and 21, when we can legally purchase alcohol and buy a handgun. Irrespective of where we draw the line between the impulsiveness of adolescence and the wisdom of adulthood, few of us would argue that a child of six, eight, 10, or 12 has sufficient command of his mind and emotions to make morally astute decisions. Which raises the following slightly troublesome question: what influence do our early years have on our ability as adults to make wise and responsible choices?

Whether we are black or white, millionaires or welfare recipients, university professors or high school dropouts, a “margin of choice” is always open to us, Shelby Steele writes in The Content of Our Character, his celebrated 1990 book on the origins and persistence of racial inequality. Despite our particular circumstances, “choice lives in even the most blighted circumstances.” The claim that a “margin of choice” is open to us all, irrespective of the challenges we face, is, viewed in isolation, a harmless assertion. Perhaps even a beneficial one, if the popularity of self-help books is an indication of their efficacy. Certainly, the idea that choice lives even in blighted circumstances—that choice does not die, simply because our personal circumstances are unfriendly or oppressive—is more compelling than its opposite, which is that adverse circumstances at any stage in our lives are always and inevitably soul crushing. But Steele is not a disinterested observer trying to chart the subtle boundaries of individual choice. He arrives at his key foundational principle—“choice lives in even the most blighted circumstances”—because he needs a way to explain the persistence of racial inequality despite the changes brought about by the Civil Rights Movement. “Race does not determine our fates as powerfully as it once did,” he states confidently. Even under slavery and Jim Crow, black people exercised a margin of choice. Even during the worst periods of physical and emotional violence, black people were individuals who responded to their circumstances with resilience and creativity. And with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he argues, the margin of choice open to black people widened dramatically.

That race is less influential in determining the fates of black people than it once was is a statement with which even the most dogmatic anti-racists and defund-the-police activists can agree. What makes the “margin of choice” claim the pillar of a distinctly conservative worldview are the arguments that follow. The individual is the “seat of all energy, creativity, motivation and power,” Steele writes. It is individual actors, not families, communities, or governments, who possess the power to change their lives. We are each largely, if not entirely, he insists, responsible for our successes and failures.

It is important to point out that Steele does not focus on personal responsibility in order to chastise people who he believes do not exercise their responsibility wisely. He emphasizes personal responsibility because he is convinced that once we understand the source of our individual power, we can “choose and act, and choose and act again, without illusions.” Why do racial gaps persist? “Personal responsibility is the brick and mortar of power,” Steele writes. “The responsible person knows that the quality of his life will pretty much reflect the quality of his efforts.” Racial gaps persist because too many African Americans have failed to exercise their personal responsibility. And why have they failed to do so? Do black people have a unique aversion to exercising their freedom? At this point in his argument, Steele makes two apparently contradictory claims. On the one hand, he argues that black people have been mistakenly led to believe that their efforts to improve the quality of their lives depend on the actions of others (government and the white majority). On the other hand, he claims that black people have exercised their “margin of choice” by choosing to believe in their own racial inferiority.

Before we investigate these two seemingly incompatible claims, I want to spend a moment discussing a German philosopher whose view of human freedom has a great deal in common with that of modern black conservatives. Immanuel Kant understood that our passions, inclinations, and desires buffet us in our daily lives. He recognized that we have many cravings and impulses, and that these undeniably shape our behavior. Nevertheless, he insisted that we could deliberate internally about our duties and obligations, and choose to align our behavior with these values when they came into conflict with our baser instincts. This ability to reflect and act intentionally is what separates us from other animals, and what gives our lives meaning and dignity. We are not, Kant insisted, at the mercy of causal laws over which we have only a vague understanding and little if any control. We can choose between right and wrong. We praise and blame, reward and punish, precisely because we can deliberate on the ends we seek and have the power to align our actions with our chosen ethical principles.

And if this is not quite such a clear-cut choice? If external forces often compromise or derail our independence? Kant feared that if our actions were determined by some mysterious combination of our biology, environment, history, and culture, we would lose our status as fully moral beings. He rejected insights from the nascent social sciences that suggested our freedom might be mildly or seriously compromised because he desperately wanted to believe that we could free ourselves from tyrannical leaders, tyrannical ideas, and the tyranny of our ignorance, both about the larger world and about ourselves.

Preserving human dignity was Kant’s great philosophical project. Without free will—without a high degree of self-mastery, without a wide “margin of choice”—we would not be moral agents worthy of praise or blame. If our choices were pre-determined by some combination of our genetic and cultural inheritances, then morality—the foundation of human dignity—would be an illusion. Now, whether we agree or disagree with Kant’s basic argument, there is a key point at which Kant and contemporary black conservatives are sharply at odds.

Kant did not believe that we are free to make bad choices. If we choose poorly, this is evidence that we are not in fact free. If we are truly autonomous creatures, which means not being pushed and pulled by external forces, this means we also cannot be pushed and pulled by other people’s ideas about what we should value and respect. We can be too ignorant or too immature to exercise our freedom, but it is inconsistent to argue we can freely choose to be ignorant or immature. Rich or poor, under- or over-educated, we can reflect on our goals, duties, and obligations, and act in accordance with what we value. We cannot freely choose a set of duties and obligations that undermine our freedom. Black conservatives, in contrast—at least those who belong to Steele’s school of individual responsibility—argue that we can freely choose to believe things about ourselves and the broader world that are patently false.

III.

As elementary school students, do we choose whether our teachers take a particular interest in our success? As high school students, do we choose how many neurons light up in our brains when we do our math homework or write a research paper? As husbands and wives, do we choose to be faithful to our spouses—or is it the case that the men and women who take pride in their self-restraint have never been seriously tested?

Although Steele freely admits he is not a professional psychologist, the theory he assembles to explain the persistence of racial gaps rests almost entirely on psychological assumptions of a speculative nature. These assumptions are not wildly implausible, but they are at least as likely to one day be proven false by a well-designed psychology experiment as confirmed. These kinds of speculative gambits can lead to powerful insights, but they are generally inadequate to carry the weight of an entire political program, as they do in Steele’s case. “Black anger always, in a way, flatters white power,” Steele writes. Both races “have a hidden investment in racism and racial disharmony despite their good intentions to the contrary,” because power defines their relations, and “power requires innocence, which, in turn, requires racism and racial division.” The power a self-identifying victim of a past injustice finds in his victimization “may lead him to collective action against his society, but it also encourages passivity within the sphere of his personal life.”

These claims are not outlandish, but they are certainly contestable, and stringing together a set of highly contestable assumptions generally arouses suspicion in an attentive reader. Lower-class blacks who struggle with poverty—as well as middle-class blacks who fail to reach the heights of their professions—cling to their identity as victims because doing so is easier than accepting responsibility for their less-than-ideal circumstances? Now, students of human nature have certainly written a great deal over the years about our fraught relationship with freedom. And history, both ancient and modern, is replete with examples of how human beings exercise their freedom by choosing to support political leaders who promise tribal supremacy or international prestige in exchange for their once-precious liberties. Exercising our freedom has certainly proven to be a consistent challenge for almost all members of our species. But is it reasonable to conclude that contemporary barriers to black progress are “clearly as much psychological as they are social or economic,” as Steele confidently asserts? Is it reasonable to claim that black people are “victimized as much by our own buried fears as by racism” past or present?

How exactly people can choose to be victimized by buried fears, I’m not quite sure. I also find it a bit disingenuous to argue that barriers to progress for black people are as much psychological as social or economic when we know that social and economic barriers have powerful psychological effects. But let us set aside such quibbles for the moment, so we can focus on the heavy lifting Steele asks his psychological assumptions to do. Steele needs his buried-fears, innocence-as-power, and burden-of-freedom theses in order to explain the persistence of racial inequalities without recourse to the kind of explanatory variables that liberal social scientists tend to emphasize, such as job losses in the manufacturing sector or the depletion of the urban tax base as white families (and later black middle-class families) moved to the suburbs. “If conditions have worsened for most of us as racism had receded, then much of the problem must be of our own making,” Steele declares. And black people can’t fully admit this to themselves, he argues, not because they might find other explanations more convincing, but because it would “cause us to lose the innocence we derive from our victimization.”

Why have so many black people, over multiple generations, joined the “cult of victimhood”? Steele points to two primary mechanisms to explain this mass conversion. The first is power-hungry, self-interested political leaders. After the Civil Rights Movement, black leaders, competing with each other for power and influence, rejected Martin Luther King’s integrationism in favor of a militant, confrontational posture toward white America (that this change may have had something to do with the fact that the victories of the Civil Rights Movement did not have a discernible impact on the lives of many black people is left unconsidered). This argument is not actually as controversial as it may at first appear. Most politicians, black and white, tell their constituents what they want to hear, and often have a hard time reflecting on the influence their personal ambition has on their political positions (this is precisely why James Madison argued that one of the primary tasks of institutional designers is to ensure that ambition counteracts ambition). Black leaders need not be more self-interested than leaders of any other race or ethnicity for his criticism to be valid. But even if we assign significant blame to a failure of leadership, we still have to explain why self-serving public figures found such a receptive audience for their message.

Steele never downplays the brutality and suffering that has defined most of African American history. “No one can deny that blacks were horribly victimized in the past,” he writes. Slavery and segregation were terrible evils that did unimaginable damage to black people. But these gross injustices ended with the triumph of the Civil Rights Movement, he argues. Racism may not have ended with these legislative victories—blacks certainly did not go from unequal to equal citizens overnight—but securing equal rights meant that the greatest external barriers to black advancement had been lifted. Although challenges remained, progress in the black community now reflected primarily the actions of black people.

Life for black people obviously changed for the better with the passage of civil rights legislation. Liberals and progressives would happily concur, though they would of course debate how much better, and what still needs to change to create a truly equal-opportunity society. But Steele has no interest in this kind of nuanced debate. For Steele, we can draw a stark line between Before the Civil Rights Acts (BC), when black people were victims of a racial caste system, and After Discrimination (AD), when the most significant obstacles to black progress were lifted and the primary challenge for black people became psychological. Steele’s near-biblical argument is that securing equal rights was necessary and sufficient. Subtle forms of racism may linger, but demanding preferential treatment from the nation that once persecuted them is not only unproductive, but counterproductive, since it shifts agency from the only actors—black people themselves—who are actually equipped to improve their circumstances. The legacy of slavery and segregation is not an economic, social, and cultural inheritance that puts African Americans at a disadvantage relative to other groups but a semi-conscious embrace of victimhood that provides psychological ballast for black people unnerved by a sense of racial inferiority.

And this is the great challenge black people face today. When we think of ourselves as victims, Steele argues, “we are released from the responsibility for some difficulty, spared some guilt and accountability.” Relinquish our responsibility, and we relinquish the only power we have to positively impact our own lives. “Injustice is what gives the claim of victimization its magic, its power to spray the onus of responsibility on others,” and this is the trap into which black people have fallen. Victimhood (looking backward) and individual agency (looking forward) are at odds. People who see themselves as victims of a historical injustice unwittingly surrender their freedom and power to people and institutions that are largely indifferent to their fates.

The problem is not that the civil rights laws were not as impactful as many had hoped, or that there was bitter resistance to integration all over our country, including in the supposedly less racist northern states. According to Steele, the problem is a vision of the world that short-circuits our innate desire to succeed in life to the best of our ability. Steele makes this claim despite the fact that black women have closed the income gap with white women at all education levels, and young black men with college degrees have reached near-parity with their white counterparts. Are we really supposed to interpret these positive developments as evidence that black women, and black men with college degrees, have embraced their margin of choice, while black men without college degrees have yet to muster the courage and confidence to seize the opportunities available to them?

Steele’s race-doubt/inferiority-complex narrative fails perhaps the most basic test of a theory that tries to explain a complicated social phenomenon: it treats one of many contributing factors as the only one that matters. After centuries of being judged intellectually inferior by white people, might some contemporary black people harbor doubts about their intellectual capacities that are more debilitating than those that periodically shatter the confidence of any human being who is not pathologically incapable of a modest degree of introspection? I would not be surprised if some do. At the same time, I have never encountered a study of any kind that attempted to measure the consequences of “race-doubt.”

I grew up in the middle-class suburbs of New York City and Washington, DC. Both of my parents were academics. The percentage of men in my birth, race, and socioeconomic cohort who will spend time in prison is miniscule (I was born in 1970). The percentage of black men of my generation and socioeconomic background who will spend a chunk of their adult lives behind bars? The exact numbers are hard to find, but I suspect the percentage is similarly small (I’ve certainly never read a study claiming black men were overrepresented among white-collar criminals). But among all black men, the percentage is astonishingly high. Over 30 percent of black men from my generation will spend time in prison. So, what should we conclude from this disparity? Not, I would suggest, that poverty or a broken home or other kinds of childhood trauma completely obliterates our margin of choice, but that it would be rather foolish for those of us with numerous advantages to conclude that the primary obstacle facing less-advantaged black men is an unwillingness or inability to take responsibility for their lives.

IV.

Do we choose to maintain our composure when we find ourselves in new and stressful situations? Do we choose to swallow our pride and walk away when someone insults us in public? Do we choose to blush—or, in rare cases, cringe—when authority figures praise us?

Thomas Sowell has a reputation among progressives as a bit of an ideologue and intellectual bully, but he can be quite charming as a thinker and stylist. It is hard for a fellow social scientist not to smile when Sowell chastises academics for thinking their niche expertise qualifies them to opine on a broad range of subjects. His wit and combativeness are similarly on display when, in response to a critical book review, he writes, “If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, straw men must be a close second.” He is unquestionably a scholar who revels in intellectual combat, but he is also a skeptic and contrarian who enjoys poking holes in the conventional wisdom of the day as much as the liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith.

What makes Sowell a challenge for some non-conservative readers is that he does not interrogate his own arguments and assumptions with the same intensity and rigor he applies to his progressive foils. He has the wisdom and objectivity to declare that the “feelings and intuitions on which we build theories of how the world works are indispensable—but dangerous, precisely to the extent we confuse them with reality itself,” but the pronoun he uses in this sentence applies exclusively to liberal intellectuals. Despite the uneven (and very human, I should add) application of his analytical skills, the data-driven arguments he makes in his many articles and books do present a serious challenge to the conventional progressive narrative about the persistence of racial inequality. The empirical evidence, he likes to point out—sometimes soberly, sometimes angrily, sometimes mockingly—does not always fit with what a progressive’s ideological leanings would predict.

Sowell’s work on race revolves around two fundamental questions. The first: what are the causes of racial inequality? The second: do welfare programs alleviate poverty, as they were intended to do, or exacerbate it? Sowell answers both questions with a degree of confidence that the evidence does not support. Throughout recorded human history, “grossly uneven distributions of racial, ethnic and other groups in numerous fields of endeavor” has been the norm. This is a point Sowell makes over and over again in his work, drawing on the experience of minorities here and abroad. We have different histories, religions, parenting styles, attitudes toward education, work traditions, and definitions of success, among other things, and these cultural differences, Sowell argues, lead to precisely the kind of inequalities that progressives attribute to racism.

It’s important to point out that Sowell is not dismissive of the impact of racism. The history of race is a story of “hostility and hatred,” he writes in Intellectuals and Race, and “racial issues show no sign of going away.” At the same time, no subject is more in need of dispassionate analysis: race needs to be studied in an international, comparative context so that we do not misunderstand the nature of our own racial challenges. Two examples of the kind of comparative analysis he supports will make his argument more concrete.

In a 1979 essay for Commentary, Sowell presents data on the percentage of various ethnic and racial groups that were practicing lawyers, doctors, or teachers in our country. Most progressives would assume that white people would dominate these high-status jobs. Sowell reports that 15 percent of black West Indians fit into this employment category. The figures for Japanese- and Chinese-Americans were 18 and 25 percent, respectively. The percent of white Americans with the same impressive credentials? A mere 14 percent. Counterintuitive statistics like these do not prove that there was no racism in America in the early 1980s, but they should give progressives pause. Skin color certainly does not map as neatly onto socioeconomic status as many progressives assume.

A second example. The majority of Chinese immigrants who arrived in the United States before World War II came from a specific province in southern China. As a group they prospered, despite legal discrimination and widespread anti-Chinese sentiment. The majority of Chinese immigrants who arrived after World War II came largely from other parts of the country. They generally lacked the education and work experience of first-wave Chinese immigrants, and a dearth of marketable skills forced them to take low-paying jobs and live in poor urban neighborhoods. The difference between these two groups of Chinese immigrants was clearly something other than race.

At a minimum, data like these complicate the anti-racist narrative. How are we to explain the success of some black and other non-white groups in our society, if various forms of white supremacy have always reigned supreme? The answer, Sowell insists, is as obvious as it is unpopular. We no longer live in a society in which racism is a significant hurdle for black people. The primary reason some groups succeed in our country while other groups, unfortunately, struggle, sometimes for generations, is cultural. A group’s norms and values—not its race or ethnicity—determines its relative success. The progressive assumption that black people are the victims of subtle or not-so-subtle forms of racism is simply mistaken. The success of black and other non-white immigrant groups proves that racism cannot explain the persistence of racial inequality.

The purpose of Sowell’s comparative economics is not only to demonstrate that inequality is the norm throughout the world, rather than the exception that only government policy can fix, but to get his readers to focus on what successful minority groups have in common. Fixating on white and black differences in educational attainment or rates of homeownership, he argues, are distractions. Instead of asking why white people perform better than black people on some measure of success, and assuming it must be a consequence of some combination of past and present racism, we should ask why Japanese-Americans have higher incomes than Pakistani-Americans, why Nigerian-Americans have higher rates of entrepreneurship than Sudanese-Americans, and why immigrants from northern Italy have fared better socioeconomically than immigrants from the south of the same country. The answer, yet again: cultural differences. The disparities between groups in education, crime, income, and many other metrics are real and worthy of study. But attributing them uncritically to racism is as misguided as attributing them to differences in IQ, which was also once fashionable among progressive intellectuals.

Sowell has assembled a great deal of evidence over the course of his career in support of the claim that inequality among different racial and ethnic groups is natural and widespread. And yet, this evidence doesn’t tell us anything about the cause of inequality in any particular case. Sowell and many other conservatives are convinced that a comparative analysis largely settles the debate over the cause of racial inequality here in the United States. But if ever there is a case in which the particulars matter, I would think it would be the case of African Americans. Is it really that methodologically sound to compare immigrants to our country—people who generally make great efforts to come here, and who arrive with the expectation of making substantial personal sacrifices to ensure their children have better lives than they did—with a native population that endured centuries of slavery, and then a hundred years of a state-supported racial discrimination? The majority of African Americans, after all, were deprived of the very education and work experience that Sowell rightly argues enabled past immigrant groups to flourish. Can conservatives who lean heavily on cultural differences to explain racial inequality really afford to ignore the culture-shaping legacy of slavery and segregation?

If the legacy of slavery and segregation at least partly explains the persistence of racial inequality, some kind of reparations or affirmative action program would be justified in the short- and medium-term. If, on the other hand, the cultural differences that Sowell claims largely explain racial inequality are not a product of centuries of terror and violence, but of natural forces and processes—which is what he argues, as we will soon see—then the solution to racial inequality would be very different.

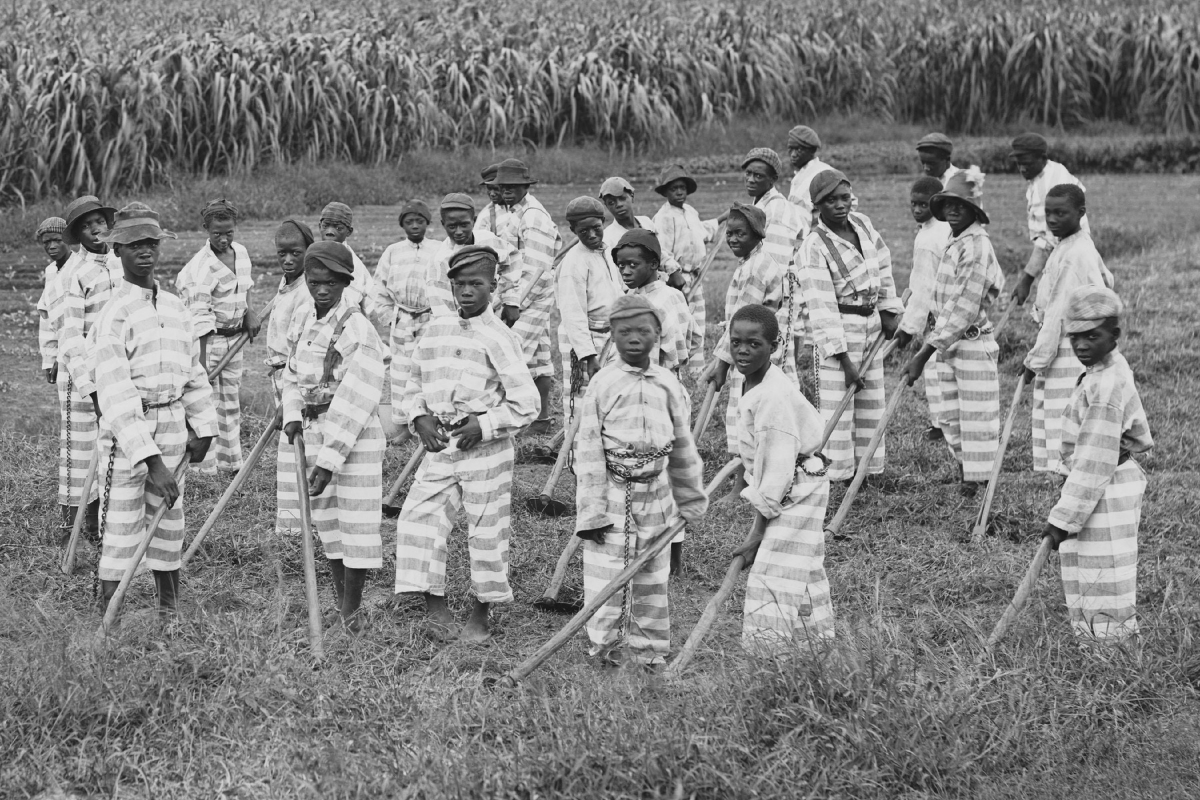

What, then, is the origin of the culture that Sowell blames for the statistical underperformance of black people? Sowell sees a causal arrow running straight from the lawless borderlands of the Scottish Highlands, northern England, and Ulster County, Ireland, to the antebellum South, where immigrants from these parts of the world arrived in the early years of our nation’s history, and on to the self-destructive behavior of many of the black residents of our urban ghettos. What these immigrants brought with them was a unique culture—a whole “constellation of attitudes, values, and behavior patterns that might have made sense in the world in which they had lived for centuries, but which would prove to be counterproductive in the world to which they were going,” Sowell writes in Black Rednecks and White Liberals. And what were the attitudes, values, and behavior patterns that would prove so counterproductive to immigrants, enslaved people, and formerly-enslaved people alike? An aversion to work, a propensity for violence, anti-intellectualism, sexual promiscuity, impulsiveness, a fondness for raucous song and dance, and an oratorical style marked by “strident rhetoric, unbridled emotions, and flamboyant imagery,” delivered by politicians, preachers, and activists with an excess of “pride, vanity, and boastful self-dramatization.”

Let me share my first (mildly censored) impression of this claim. What the hell is going on here? What in the world happened to the fiercely data-driven, methodologically rigorous social scientist? I took a deep breath and flipped back to the beginning of the chapter. My second impression (also after a little editorial oversight): Are we really supposed to believe that a black teenager from south-east DC who pulls a gun out at a gas station because he is enraged by what he perceives to be a look of disrespect from the driver of a nearby parked car is a direct cultural descendant of violent, impulsive, honor-obsessed, kilt-wearing Scottish Highlanders? Are we really supposed to believe that the best way to understand why a disproportionate number of black elementary school students are behind grade level in reading and math is the anti-intellectualism of their one-time oppressors?

It may appear to some conservative readers that I am mocking a serious scholar. But as anyone familiar with Sowell’s work would know, I am not being at all selective with my quotations or misrepresenting his claims. So, what’s going on here? Why would a scholar interested in understanding the persistence of racial inequality in contemporary America insist for his mother-of-all explanatory variables on a clan-based honor culture that emerged on another continent in the late Middle Ages? This is not a trivial question. Why would a methodologically sophisticated social scientist invest so heavily in such a speculative (and unfalsifiable) theory of interracial cultural transmission? Why would an otherwise data-driven social scientist promote such an implausible theory when common sense would suggest that the “ghetto” culture that emerged in the second half of the 20th century was at least partly a byproduct of a long history of state-sanctioned discrimination in education, housing, and employment?

A southern honor culture may have infected some unskilled black farmworkers who migrated north in the early and middle years of the last century in search of greater freedom and economic opportunity. It could very well be that common sense in this case—that the legacy of slavery and segregation has a key role to play here—is mistaken. But it is an enormous stretch to go from proposing that there might have been some degree of cultural syncretism to arguing that current black residents of Baltimore, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis have more in common with Medieval Scottish herders than, say, a person of any race or ethnicity who grows up in a high-crime, high-poverty neighborhood in our post-industrial world. So, why would a conservative scholar promote the idea of cultural osmosis over the more sociologically plausible and empirically defensive claim that groups that share similar socioeconomic profiles during periods of economic and cultural upheaval adopt similar norms, values, and behavioral patterns?

Sowell has backed himself into a corner. If the best explanation for the persistence of racial inequality is not a combination of personal and systemic racism, as progressives claim—and not the legacy of slavery and segregation, compounded by structural changes in our economy that hit unskilled black workers particularly hard, as liberals generally argue—then what causal mechanism, other than black culture, is left? By default, black culture ends up as the all-powerful explanatory factor. Racial inequality persists in our country because too many black people are beholden to a culture that promotes values antithetical to human flourishing. Poor and working-class black people do not put a sufficient emphasis on doing well in school, taking proper care of their families, or acquiring the skills they need to advance at work because, well, not because of any animus directed toward them from the external world, but because they had the great misfortune of absorbing from their poor white southern neighbors a culture that was terribly unsuited to meeting the challenges and opportunities of the modern world.

This brings us to the second major question Sowell addresses in his research on racial inequality. Why did this supposedly maladaptive “redneck” culture survive largely unchanged in a portion of the black population, despite profound differences between the rural South and urban North, and despite the passage of multiple generations? Why, in other words, did black culture stagnate?

V.

Can those of us who have always excelled in school suddenly choose to let our grades slip? Can teenagers who grow up in a middle-class family choose to join a street gang instead of a chess club or debate team? Can those of us who have effectively navigated our meritocratic system choose to turn down a job with higher status and pay even if we suspect it will have a negative impact on our family lives?

Perhaps the greatest debate of the last century in economics was between John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich von Hayek. At its most basic, it was about the extent to which governments should intervene in the free market. Keynes did not think markets were always efficient and self-corrective, and saw a productive role for government. Hayek was convinced that government interventions in the free market, however well-intentioned, would exacerbate the crises they were intended to mitigate, and create new crises that would inspire additional rounds of failed interventions, in a never-ending feedback loop.

I mention these two economic theorists because Sowell is a self-described libertarian and proud student of Hayek. The free market, he argues—not racisms of any kind or combination—best explains the persistence of racial inequality. We do not need vague and abstract concepts like systemic racism to explain racial inequality if we recognize the simple fact that, in our post-civil-rights world, employers generally hire applicants with superior educational backgrounds and work experience over candidates with inferior educational backgrounds and work experience. Once we look at the basic data, racial inequality is perfectly understandable. Progressives insist that disparities in outcomes are evidence of racism. Sowell argues that racial inequalities simply reflect two populations with different attitudes toward education and self-development.

If you want to end business cycles and economic crises, Hayek argued, end government interference in the economy. No group of government officials, no matter how smart, and no matter how honorable their intentions, can ever know what is in the minds of all consumers and producers. The “genius” of the market is that it can incorporate more information in its decision-making than even the most enlightened group of public officials, and this is why any and all attempts to control or manage the market are doomed to be counterproductive. Sowell largely echoes this absolutist argument in his discussions of race. If you want to end racial inequality, end government interference in the labor market. In other words, end affirmative action programs and the government’s attempt to alleviate poverty through misguided social welfare programs.

Welfare programs are a textbook example of how good intentions do not always produce the outcomes desired. We have a black underclass, Sowell argues, because progressive policies sap individual initiative and encourage people to slip into a state of dependency on the government. Instead of getting a good education and learning the value of hard work, members of the underclass receive a dumbed-down education and are discouraged from developing the kinds of basic skills that would allow them to lift themselves out of poverty. It is a conservative’s worst nightmare: thanks to the “benevolent” welfare state, poor people are left with no sense of personal responsibility for their predicament, and hence no internal drive to improve their circumstances. Welfare programs, not systemic or structural racism, have prevented black culture from shedding its “redneck” past.

Progressives have the whole social-welfare issue backward, Sowell argues. It is not at all compassionate or just to provide healthy adults with subsidized food and shelter because securing these necessities for ourselves and our families is a prerequisite for building self-esteem and creating meaning in our lives. In an essay titled “Human Livestock,” Sowell writes that overcoming adversity is “one of our great desires and one of our great sources of pride.” The right to housing and food translates, in practice, to the right to be dependent on government handouts. “This is a vision of human beings as livestock, to be fed by the government and herded and tended by the anointed. All things that make us human beings are to be removed from our lives and we are to live as denatured creatures controlled and directed by our betters.”

Is this attack on our social safety net a bit extreme? In his newspaper columns, and sometimes even in his books and academic essays, Sowell can be guilty of writing with the spleen and fury of a proto-Internet troll. In Intellectuals and Society, he argues that progressive policies “give people who have the handicap of poverty the further handicap of a sense of victimhood.” This is an example of an academic taking a little too much pride in his rhetorical skills. He surely knows that there are some kinds of adversity we can triumphantly overcome, and other kinds that simply grind us down and make life exceptionally difficult for the people who depend on us. Sowell’s combative rhetoric aside, it is nevertheless true, and hardly controversial, to argue that political elites often struggle to bring their policy goals to fruition. The free market, however flawed and unjust it may appear to be in the eyes of its critics, may still be better at responding to the real-world needs of consumers and producers—as well as employers and employees—than politicians and government bureaucrats. Just as self-driving cars need not be perfect to be safer than automobiles driven by humans, the free market may produce more just and desirable outcomes than politicians who believe they have the knowledge and foresight to steer the economy safely.

Is Sowell right about the organizational genius of the free market, not only in producing the right amount of bicycles and laptop computers but being more effective than governments in lifting people out of poverty? Is he right that the welfare state is to blame for “prolonging the life of a chaotic, counterproductive, dangerous and self-destructive subculture in many urban ghettos”? History provides a wealth of evidence to suggest a mostly free market is better than a clique of unelected government bureaucrats at synthesizing the vast amount of information needed to produce the optimum amount of consumer goods. But when it comes to lifting people out of poverty, the story is more complex. Not merely because there is ample evidence to suggest that government programs have a better track record than conservatives are inclined to admit, but because when supporters of the free market criticize government programs, they flash the equivalent of a get-out-of-jail free card. No politician will ever win office, or remain in office, with a stump speech that insists upon the need for patience, no matter how long it takes, in the midst of a sustained economic downturn. We will never know how long it would have taken our economy to return to pre-depression levels in the 1930s, or pre-recession levels in the 2010s, if we had let the free market work its anti-poverty magic because politicians are not economic theorists who can lecture their constituents on the value of patience.

Voters have a degree of political agency—a margin of choice, we could say—and, when economic conditions take a turn for the worse, they generally expect a forceful response from their political representatives. Just as no society has built a socialist heaven in which each gets according to his needs, and gives according to his ability, no society has erected a libertarian heaven in which politicians and constituents alike stand patiently by while the free market solves our social and economic problems. We will never know how effectively a truly free market would deal with inter-generational poverty because no democratic society will ever conduct such an experiment. The practical question, as in most realms of public policy, is how to navigate the ship of state into the elusive sweet spot between two flawed and sometimes contradictory visions of how to create and preserve a just society. Not all anti-poverty programs are successful. Not all have failed miserably. It should be the job of students of poverty to identify which programs have been successful, and then to determine the likelihood that they will continue to be successful in the future, as social and economic circumstances change.

VI.

If a series of psychological studies convinces us that believing in free will correlates strongly with greater success and happiness in life, can we choose to ratchet up our faith?

I would like to propose a brief thought experiment. A hypothetical that is as fanciful as it is simple and straightforward. If interpersonal racism magically disappeared, and, in addition, our institutions were suddenly as colorblind as our citizens, would racial gaps that have proven intractable over the last few decades begin to narrow? Absent a few extreme contrarians on the Left and Right, most students of race would answer in the affirmative. Of course they would begin to narrow. But a bitter debate would quickly follow this rare moment of consensus.

Although racial gaps would begin to narrow, progressives would argue, they would do so at an excruciatingly slow pace. This is because the most pertinent racial gap in our country is the wealth gap, and the wealth gap is a reflection not only of the history of slavery but a century of legal discrimination against blacks that directly impacted their ability to generate wealth. Even if racism disappeared, the wealth gap would, in the absence of bold federal interventions, persist for the foreseeable future. The education gap would also narrow at an intolerably slow pace because the performance of children and young adults on standardized tests track with demoralizing precision to the socioeconomic status of their parents. Equally worrisome is the fact that accumulated wealth largely determines the neighborhoods in which we live and raise our children, and this means that the intergenerational consequences of living in high-poverty, high-crime neighborhoods would persist. In other words, ending racism is a necessary but insufficient condition for creating the kind of equal-opportunity, character-driven society that conservatives and progressives both claim to want.

Conservatives would be as enthusiastic as progressives about the emergence of a society in which we were all judged by the content of our character, rather than the color of our skin, and perhaps even more so, since they are generally more skeptical of human nature, and it would therefore come as a greater shock. But they would argue that the gaps in education, health, income, and wealth can only be marginally attributed to racism. Civil rights legislation in the 1960s obviously did not end racism, and it did not compensate black people for any of the violence, brutality, and economic loss inflicted upon them over the course of our nation’s history. What it did do, however, and the data on this is unambiguous, is dramatically expand the opportunities open to black people. The primary challenge facing African Americans since the end of legal segregation is not the hostility of white people or white-dominated institutions and processes that reinforce white supremacy. It is certainly not the absence of sufficiently aggressive affirmative action programs or a lack of diversity training in the corporate world. What has held black people back over the last 50 years is a combination of black leaders who selfishly put their own interests above those of their constituents, an inferiority complex that leads black people to shy away from direct competition with white people, a culture that promotes a set of norms and values that are antithetical to black progress, and welfare programs that create a mindset among recipients that is incompatible with being successful in the modern world. As much as progressives insist that racism is the source of all racial inequalities in our country, the simple, indisputable fact of the matter is that many black people, native and immigrant alike, have flourished in our country since the great legislative successes of the 1960s, and past persecution, both here and abroad, has proven to be a very unreliable indicator of current socioeconomic status.

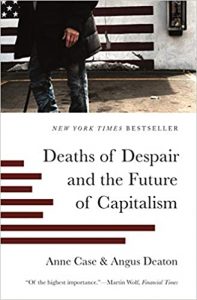

Have we learned anything new over the last two decades about the relationship between the state of our economy and the suite of behaviors that most black conservatives argue are responsible for perpetuating racial inequality? I would argue that we now know a great deal more, and that conservatives have yet to incorporate this new evidence into their thinking. Back in the early 1980s, William Julius Wilson, in The Declining Significance of Race, argued that poor blacks and whites would both suffer from a labor market that would continue to be transformed by “labor-saving innovations, relocation of industry, labor-market segmentation, and the shift from goods-producing to service-producing industries.” This is why he was convinced that “recent developments associated with our modern industrial society are largely responsible for the creation of a semi-permanent underclass in the ghettos, and that the predicament of the underclass cannot be satisfactorily addressed by the mere passage of civil rights laws or the introduction of special racial programs such as affirmative action” (he was skeptical of affirmative action programs because he believed they would only benefit black people who already possessed the education and skills needed to take advantage of them). Forty years later, Anne Case and Angus Deaton published Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, a study of the dramatic rise over the last two decades in America of deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholism. The people dying from these causes, and in much greater numbers than ever before? Members of the white working class.

The first wave of globalization and automation in the 1970s and 1980s hit unskilled black workers in our inner cities particularly hard. This is what Wilson argued was primarily responsible for the rise in black unemployment, crime, violence, drug use, and out-of-wedlock births. The current wave of globalization and automation, supercharged by the digital revolution, has had a disproportionate impact on white people without college degrees. Unsurprisingly, there has been a steep rise among the white working class in many of the same “pathological” behaviors that have long afflicted the low-income African American communities. Is this an example of the “culture of poverty” crossing racial lines once again, independent of structural changes in the economy—or does this parallel experience suggest that the inhabitants of most communities in our country will struggle in similar ways when good working-class jobs disappear?

What has eroded the foundations of working-class life? Case and Deaton attribute this development primarily to changes in the labor market that have disproportionately affected people without a college education. This has produced what they describe as a “convergence across the races.” As an example, they point out that out-of-wedlock births among black women have been declining since 1990. Meanwhile, among white working-class women without a college degree, they have doubled from 20 to 40 percent. Is this evidence of a previously unidentified white racial inferiority complex? Is this another example of politicians using a victimization narrative to undermine individual agency? Is this a southern honor culture resurfacing after a century-long dormancy? It is certainly possible for conservatives to argue that working-class whites in the 2020s share with working-class blacks in 1970s the great misfortune of living in a country with a welfare system that infantilizes its “beneficiaries” and perverts their culture, but doing so requires an almost willful disregard for the evidence.

Progressives have indeed struggled to design and implement policies that help low-income black people in the long-term, rather than merely in the short-term (anyone who has studied the mixed record of anti-poverty programs would have to agree, even if progressives would point to a range of notable successes). Black conservatives, in contrast, will never offer short- or long-term help until they recognize the weaknesses in their own intellectual tradition. We need a vibrant, big-tent black conservatism as much as we need a vibrant, big-tent Republican party, but at present it offers little more than self-help for the middle-class. Perhaps if black conservatives offered a more nuanced “vision” of the respective roles of individuals and governments in addressing racial inequality, the black community would be less receptive to the anti-racist narrative that conservatives so vehemently denounce.