Top Stories

When Men Behave Badly—A Review

A review of When Men Behave Badly: The Hidden Roots of Sexual Deception, Harassment, and Assault by David M. Buss, Little, Brown Spark, 336 pages (April 2021)

Professor David M. Buss, a leading evolutionary psychologist, states in the introduction of his fascinating new book that it “uncovers the hidden roots of sexual conflict.” Though the book focuses on male misbehavior, it also contains a broad and fascinating overview of mating psychology.

Sex, as defined by biologists, is indicated by the size of our gametes. Males have smaller gametes (sperm) and females have larger gametes (eggs). Broadly speaking, women and men had conflicting interests in the ancestral environment. Women were more vulnerable than men. And women took on far more risk when having sex, including pregnancy, which was perilous in an environment without modern technology. In addition to the physical costs, in the final stages of pregnancy, women must also obtain extra calories. According to Britain’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, pregnant women in their final trimester require an additional 200 calories per day, or 18,000 calories more in total than they otherwise would have required. This surplus was not easy to obtain for our ancestors. Men, in contrast, did not face the same level of sexual risk.

These differences in reproductive biology have given rise to differences in sexual psychology that are comparable to sex differences in height, weight, and upper-body muscle mass. However, Buss is careful to note, such differences always carry the qualifier “on average.” Some women are taller than some men—but on average men are taller. Likewise, some women prefer to have more sex partners than some men—but on average men prefer more. These evolved differences are a key source of conflict.

One goal of the book is to highlight situations in which sexual conflict is diminished or amplified to prevent victimization and reduce harm.

Because of the increased risk women carry, they tend to be choosier about their partners. In contrast, men are less discerning. Studies of online dating, for example, find that most men find most women to be at least somewhat attractive. In contrast, women, on average, view 80 percent of men as below average in attractiveness. Another study found that on the dating app Tinder, men “liked” more than 60 percent of the female profiles they viewed, while women “liked” only 4.5 percent of male profiles.

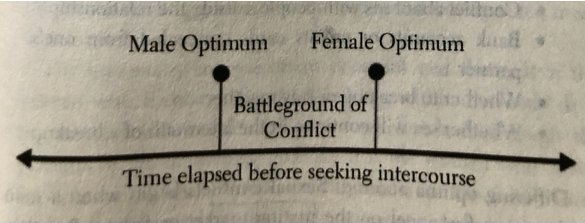

The book provides a simple figure to understand the ongoing conflict between men and women.

Men are constantly trying to manipulate women into moving closer to their preferred optimum, and women are likewise relentlessly influencing men to inch closer toward theirs. Buss writes, “If women and men could agree in advance on a compromised middle-ground solution that was perfect for neither but acceptable for both … they could avoid many of these costs.”

Because sexual risks are higher and sexual mistakes are more dangerous for women, they prefer to wait longer to evaluate a potential partner for suitability. For men, sexual mistakes are viewed differently. Research indicates that when asked to reflect on their sexual history, women are more likely to regret having had sex with someone, while men are more likely to regret having missed out on sexual opportunities.

Even in the most egalitarian countries, men prefer more sexual partners compared to women. In Norway, researchers asked people how many sex partners they would prefer over the next 30 years. On average, women preferred five, men preferred 25. Even the desire to kiss before intercourse differs between the sexes. About 53 percent of men report that they would have sex without kissing, while only 14.6 percent of women would have sex without kissing. These different preferences can give rise to sexual conflict.

I once watched an episode of Mad Men where the handsome protagonist Don Draper is unfaithful to his beautiful wife, Betty. The young woman watching with me asked, “Why would he cheat on her? She’s so pretty.”

Buss explains why: “Many men are burdened by lust for a variety of different women, constant cravings that cannot ever be fully satisfied … It explains why a handsome movie star such as Hugh Grant would have sex with a prostitute, despite having Elizabeth Hurley, a gorgeous model and actress, as his then steady girlfriend.”

* * *

The book reports chilling research about predatory males. Researchers videotaped individuals walking down the same block in New York City. The tapes were shown to 53 prison inmates convicted of violent crimes. Inmates showed strong consensus on who they would victimize. They chose individuals who moved in an uncoordinated manner, with a stride that was too short or too long for their height. In another set of studies, researchers found an association between men’s chosen targets and women’s self-reported frequency of having been sexually victimized in the past. This suggests that women suffering from unwanted sexual encounters inadvertently emit cues that predatory males can detect.

Who is most prone to inflicting costs on members of the opposite sex? Buss relays research on Dark Triad personality traits which encompass narcissism (entitled self-importance), Machiavellianism (strategic exploitation and duplicity) and psychopathy (callousness and cynicism). Men high on these traits are more likely to harass, stalk, and abuse women.

For women high on Dark Triad traits, research indicates that they are more likely to lure attached men away from their partners for sexual encounters and are more likely to use sex to get ahead in the workplace. They are also more likely than other women to say they’ve had fewer sexual partners than they really have had. Deception is often prevalent in the mating market. And deception involves an understanding of what the opposite sex desires. For instance, on dating websites, men exaggerate their income by roughly 20 percent on average and round up their height by about two inches. Similarly, women on dating websites round their weight down by about 15 pounds.

The book discusses a key source of sexual conflict stems from two biases: Sexual over-perception and under-perception. On average, men have an over-perception bias—mistakenly inferring sexual interest from women that is not present. In contrast, women have an under-perception bias—mistakenly overlooking existing sexual interest from men. Relatedly, research led by psychology professor April Bleske-Rechek found that men are more likely to be attracted to their female friends than vice versa and were more likely to believe their female friends were attracted to them. In contrast, women were typically not attracted to their male friends, and assumed this absence of attraction was mutual. Still, there are individual differences. Men who score high on narcissism are especially prone to incorrectly picking up on nonexistent interest from women.

Another situational factor giving rise to sexual conflict is a shift in living conditions. Buss observes that in our evolutionary past, young women were typically surrounded by kin and other social allies. Their mere presence deterred would-be predators. In contrast, many young women in the modern West graduate high school and go straight to college. They are then in a new environment without such familial allies, surrounded by evolutionarily novel drugs, hookup culture, and immature young men.

* * *

In addition to presenting research on the variables that predict sexual aggression and conflict, Buss relays research on mating strategies. For instance, the book shares findings indicating that people in committed relationships often cultivate “backup mates” in case their current relationships flounder. Even people happy in their relationships will seek this form of mate insurance, often creating and maintaining friendships with members of the opposite sex.

One line of research from Buss and his colleagues found that heterosexual people seek different qualities in same-sex versus opposite-sex friends. For same-sex friends, men and women prioritized personality and social intelligence. For opposite-sex friends, though, men assigned greater value on attractiveness, whereas women placed greater value on economic resources and physical prowess. This implies that men and women prioritize the same features for opposite-sex friends as they do for romantic partners.

Why do people cheat on their romantic partners? For men, it appears that the main reason they stray is the desire for sexual variety. In fact, men who cheat are just as happy in their marriages as men who are faithful. In contrast, women who stray are often unhappy. Women who have affairs often want to detach themselves from relationships in which they are unsatisfied and seek a better partner. In fact, only 30 percent of men report falling in love with their affair partners, while for women it is 79 percent.

Intriguingly, people tend to hold double standards about what counts as cheating. For example, 41 percent of men report that oral contact with the genitals of someone other than their partner counts as “sex.” But what if their partner had oral contact with someone else’s genitals? For this question, 65 percent of men said that would count as sex.

What about for women? 36 percent of women said if they had oral contact with the genitals of someone other than their partner, that would count as sex. But 62 percent said if their partner had oral contact with someone else, that would count as sex.

It seems people believe they can engage in oral sex and it would be just fine. In contrast, they would view it as a betrayal if their partners engaged in the same behavior.

Beyond romantic infidelity, Buss reports data on resource infidelity. One survey in New York City found that about four out of 10 married women and men revealed that they had a secret bank account. Another study found that 80 percent of married people admitted to hiding money from their spouses. This doesn’t exactly reflect well on people. But as Buss stresses throughout the book, “adaptive” does not mean “morally good.” Often, cultures create moral norms to suppress certain behaviors that might be beneficial for the individual but bad for the community (e.g., stealing).

Because of the possibility of cheating, people engage in “mate guarding”—vigilant behaviors that are enacted to deter others from seeking a sexual encounter with their partner. This is more common than many think—87 percent of men and 75 percent of women report that they have attempted to lure someone out of their existing relationship for a short-term sexual encounter.

Men are more likely to engage in mate guarding if their wives are particularly attractive. Interestingly, women are slightly less likely to engage in mate guarding if their husbands are physically attractive. In contrast, women are more likely to engage in mate guarding if their husbands are wealthy.

Yet another source of relationship conflict is when there is an attractiveness mismatch between a romantic pair. People with partners who were equally or more desirable to themselves reported greater satisfaction in their relationships. However, the higher-value partner is more likely to cheat and more likely to leave the relationship, because they simply have more options.

Still, if the more attractive person believes that their own partner is more desirable than their alternatives, they tend to be content. But this is difficult to sustain in the modern world. Dating apps have opened up vast pools of potential mates. In a small town, a 10 can be happily married to an eight. But if they can pull out their phone and find nines and 10s, they may be more likely to stray.

In fact, Buss suggests that the modern world has created a form of runaway sexual competition. Some see celebrities, pseudocelebrities, and influencers on social media and believe that such idealized images represent their competitors. Furthermore, the proliferation of “sexy selfies” may be due in part to economic inequality, as women compete to earn the attention of a shrinking pool of economically successful men.

Relatedly, those lower in mate value show more controlling and aggressive behavior toward their partners. For instance, taller men report less jealousy in their relationships than shorter men. Shorter men are more likely to engage in mate guarding to prevent their partners from straying. Similarly, women and men with lower mate value are more likely to engage in physical aggression against their partners and inflict injuries on them.

* * *

The book shares alarming findings on intimate partner violence. For example, studies conclusively indicate that young wives are more likely to be victims than older wives. Some have suggested that this is because young women are more likely to have young male partners, who are particularly prone to aggression. However, young women married to much older men—five to 25 years older—are especially likely to be abused. Buss suggests that because young women are more likely to be mate guarded because they are more likely to get pregnant. Thus, their partners are more controlling to deter the possibility of mate poaching.

Disturbingly, men are twice as likely to perpetrate violence against their partners when their partners are pregnant. A possible explanation is that such men suspect that their partner is pregnant with someone else’s child. Indeed, Buss reports research that women abused while pregnant were in fact more likely to be carrying the child of a man other than their current partner.

Furthermore, having stepchildren predicts intimate partner violence. A Canadian study found that women with children from a previous partnership sought protection from shelters for battered women at five times the rate of same-aged women whose children were all related to their current partner. “From the perspective of the stepparent,” Buss writes, “a stepchild is typically viewed as a cost, not a benefit, of the mating relationship.” Relative to related children, men, on average, are more reluctant to give their time and resources to unrelated children. In fact, being a stepchild is the single largest risk factor for being killed as an infant or young child, even controlling for poverty and socioeconomic status. Relatedly, studies on infants show that they have a unique fear of unfamiliar males.

Throughout the book, Buss is careful to note that just because a behavior is adaptive or “natural” does not mean it is morally good or desirable. Diseases are “natural,” yet modern science has developed vaccines and medical procedures to eliminate these ailments. Likewise, people can implement personal, social, and legal instruments to curtail the darker facets of male psychology.

And as the title indicates, the book explores the topic of sexual coercion. Perpetrators of sexual harassment tend to target young, single women. Indeed, one study found that although women between the ages of 20 and 35 comprised only 43 percent of the workforce, they filed 72 percent of the harassment complaints. Another study found that women are far more fearful of rape than other crimes, such as being beaten up or being threatened with a knife or a gun. Buss suggests that this key fear drives women’s fear of other crimes. Indeed, although men are more likely to be physically assaulted and murdered than women, women still report more fear of such crimes. But once women’s fear of rape is statistically controlled, they are no longer more fearful than men of other violent crimes. This fear, too, appears to be related to age. Women aged 19 to 35 showed the greatest fear of sexual assault, and this fear drops with age. Women in their 60s report more fear of home break-ins than rape. Overall, the evidence suggests that women’s fears track with their actual age-related vulnerability, indicating a powerful psychological wisdom.

Unsurprisingly, men and women react to sexual harassment in ways that accord with evolutionary psychology. When men were asked how they would feel if their co-worker of the opposite sex asked them to have sex, 67 percent of men said they would be flattered and only 15 percent said they would be insulted. In contrast, 63 percent of women said they would be insulted and only 17 percent said they would be flattered.

Intriguingly, men and women converge in their answers when asked what percentage of men would be willing to commit rape. Women estimate that about one-third of men would commit rape if there were no consequences, and about one-third of men report that they would commit rape if they believed they could get away with it.

* * *

What kind of men? As mentioned above, Dark Triad traits predict sexual aggression. Perhaps more surprisingly, research indicates that high-status men are particularly likely to commit sexual assault. Buss writes, “men with money, status, popularity, and power are more likely to be sexual predators.” These results parallel the disconcerting finding that men who use sexual coercion have more partners than men who do not. A popular idea is that men who are desperate or deprived of chances for sex will be more likely to use coercion. This is known as the “mate deprivation hypothesis.” However, studies suggest the opposite is the case. Men who have more partners report higher levels of sexual aggression compared to men with fewer partners. Furthermore, men who predict that their future earnings will be high also report greater levels of sexual aggression relative to men who predict that their future earnings will be low.

One contributing factor may be an empathy deficit—the book reports that high status is linked to lower levels of empathy. Men high on Dark Triad traits are viewed as more attractive by women, are more likely to have consensual sexual partners, and are more likely to engage in sexual coercion.

This book is an enthralling exploration into sexual conflicts, mating psychology, sex differences, and more. Buss closes with comments on how to mitigate reprehensible male behavior. Though evolution has given rise to darker aspects of male psychology, evolution has also instilled tendencies that can suppress it. “We are a rule-following species,” Buss notes. We have evolved to care deeply about social status, reputation, group opinion, and moral norms. We can use some facets of our evolved psychology to dampen others.