Apocalypse

Bunker Boy: Preparing for Apocalypse Since 1979

The film gave me nightmares and panic attacks. I did what I could with such difficult information.

When I was 11 years old, back in 1979, my mother helped me build a nuclear bunker. It was kitted out with about 50 cans of beans and pulses, tuna, and peaches; every shelf was stuffed with bags of rice, crisps, and chocolate bars; I lined the walls with tin foil (to protect us from gamma radiation from the impending nuclear blasts), and we had three torches, a huge supply of batteries, a home doctor manual, a first aid kit, iodine, a ton of toilet roll, and a bucket for human waste.

Although it wouldn’t have been particularly effective in a nuclear war and was little more than the closet under the stairs with all the shoes and mops thrown out to make space, this was my first serious attempt at “prepping” for the end of the world. I spent a lot of time in that little bunker reading up on what to do when the bombs fell and the end began. I recall being worried that I might have to choose between my dog and my grandmother because there wasn’t enough space to fit us all. And there was the terrifying question of the weapons we’d need to protect our survivalist stash from starving marauders. My father offered me his Sgian Dubh (a traditional Scottish knife) but my mother was dead against it because, as hippies, we were pacifists.

This was all a little extreme, perhaps, but my family was an odd bunch of social misfits, and we lived very close to the thing we feared the most, nuclear power. Dounreay Nuclear Power Station, on the remote north coast of Scotland, was only 24 miles away and my uncle worked there. Red Sammy (a fierce union man) often terrified us with tales of nuclear processing accidents at the power station that had been hushed up. Like the “missing mass” of uranium—the size of a football—that had just vanished and that the staff liked to joke was being kicked around on a local football pitch. Or there was that time that a “process worker” came all the way home from Dounreay in his white rubber radiation protection boots, and the street, the bus and his house had to be completely gutted by men in hazmat suits, then the whole thing hushed up.

My father, a highly emotional political extremist at the best of times, was vehemently anti-nuclear, and a month before I built my bunker, he took my seven-year-old sister and I to a screening of the film The War Game. It was a pseudo-documentary about international nuclear war that had been banned by the BBC and was being shown illicitly by CND (The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament) on a 16mm print in our local community hall. We were being anti-government, which was something my father loved more than anything.

Perhaps it wasn’t the wisest thing to subject two, already emotionally vulnerable children to. The images in that film of innocent civilians blinded by nuclear flash, of homes incinerated, of radiation sickness and peeling skin, of nuclear fallout and survivors scavenging in ruins, had an immense impact on my 11-year-old mind. A mind that was already rather troubled by being the weird hippie punch-bag at school. Also disturbing was the fact that this film had been banned. As my father instructed me, “the government are lying bastards and don’t care if we all die.” So, this was my introduction to conspiracy theory mentality—the sibling of Bunker Mindset.

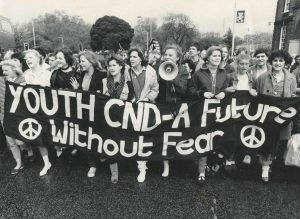

The film gave me nightmares and panic attacks. I did what I could with such difficult information. I tried to be practical: I joined Youth CND and built my bunker under the stairs, following instructions that were taken from Protect and Survive. This was a series of government information videos made to be screened on all channels 72 hours before a supposed nuclear strike on the UK. The footage was leaked from government archives and shown on Panorama on March 10th, 1980. It was also shown around community centres by CND, which was where I saw these exercises in propaganda, intended to instill in the public a sense that they could “do something” to save their families in the event of all out nuclear war. The terrifying videos showed you how to build a bunker out of tables, doors, and bags of earth and how to create a bunker under your stairs. I took all this very seriously, all the way to building the bunker at age 11. I was convinced not only that the end of the world was coming very soon, but that humanity deserved it.

Decades later, therapists and friends would comment that I suffered from “persecution paranoia” and was drawn to totalising fantasies of doom, succumbing to periods of morbid depression. I don’t blame the Cold War as such (or the leaked Protect and Survive videos), although many studies now show that it left its mark on the mental health of my generations who grew up “in the shadow of the mushroom cloud.”

My Bunker Boy mentality probably came from the way in which my counter-cultural family relished our us-against-them status. A good example of this would be the heroic task that my little sister and I undertook to shut down Dounreay Nuclear Power station so as to avert nuclear war one Saturday morning in 1980.

As Youth CND members, we knew even at that tender age that Dounreay was actually creating weapons grade plutonium for bombs and was not really a power plant at all; we also knew that it was blast zone number two for the Soviets, after London, so we were bound to get nuked. Precocious children that we were, we went round the town, door by door, asking locals to give us their signatures on a CND petition to shut down the nuclear plant. A naïve enterprise, given that almost half of the town had family members who worked in the power station and another quarter had work dependent on it. I have a vivid memory of being chased out of our favourite sweetie shop by a furious shopkeeper wielding a broom and yelling that we were “banned for life.” My sister and I found this very hard to take, given that CND had told us that radioactive particles had been found on the beach near the power station (Sandside beach) and the local town of Thurso had Leukaemia clusters.

What came from the failed petition and our bunker was the sense that my family were very much alone; that everyone around us was blind, ideologically brainwashed, and on top of that, these ignorant locals were all doomed to die when the nuclear war started. Not only them but the ignorant masses all over the UK. My family would be the only survivors! Secretly, we felt rather proud of ourselves, as my parents helped me line the bunker walls with tin foil and Sellotape.

So, that was where it began at the age of 11—bunker mentality, survivalist mindset. And with it was a darker undertow of something like vengeance against the world for chasing us out with a broom stick and sneering at us for being hippies. In the many teenage nightmares I had of Armageddon, I saw myself walking unscathed through snowdrifts of nuclear fallout in the streets that were killing everyone else. Give a bullied, maladjusted outsider kid an apocalypse to play with and this is what you get. A revenge fantasy masked as “saving the world.”

Catastrophizing, neuroscience tells us, is a way to give yourself an addictive adrenaline high. You can get hooked on that sense of perpetual panic. I’d spent a good deal of my adult life trying to shake off the survivalist mindset and the dissociation that came with it, but when in 2012, at the age of 45, my wife and I were commissioned to work on an American TV movie—American Blackout for National Geographic—I was thrown back into it again.

Like The War Game, the TV movie was a pseudo-documentary about a near apocalyptic disaster. The subject was a terrorist strike on the American power grid that brings society to and then beyond the brink of collapse.

Advertised during the Superbowl, and used to introduce the second season of Doomsday Preppers, American Blackout went on to strike a nerve in American culture. With an estimated 30 million viewers, it was debated in US congress and became part of the canon of apocalypse survival movies and a hotly debated subject of prepper and survivalist chatrooms, blogs, and vlogs. The preppers in the US and the UK thought my wife and I had got our facts pretty much right about the step by the step-by-step processes of civilisational collapse. We were pleased, yes, but also terrified by what we’d discovered in writing the film.

It wasn’t so much the film itself but the dossiers of research material.

We’d had the full support of National Geographic researchers and they gave us incredible access to information from FEMA, the US Energy Dept, and professors and researchers of collapse studies at Columbia and Delaware universities; professors of national security strategy at the National War College; Washington, grid engineers; the SANS institute; experts on homeland security and cyber security; scientists at the RAND institute; the director of CSIS; and the US Cyber Consequences Unit. We were only able to use about two percent of all that we discovered about the house of cards that is modern society, and the other 98 percent haunted us.

What the models, histories, data, and calculations showed was that Western nations with their global “just in time” supply chains of food and fuel were highly precarious, if not downright foolish to operate in the ways they did.

The net of economic interconnectedness meant that no developed countries could survive without the others, none were self-sufficient; and all would spread their crisis to others. Although the research back in 2013 was about a terrorist cyber-attack that shuts down the US power grid, my wife and I learned that the tipping point we were so close to in developed nations could be brought about by other crises—eco-disaster, economic collapse, shortages such as “peak oil,” political unrest, civil war, or an unexpected pandemic.

It was then that we actually became like the subjects of the programme we were working on. Secretly, we started “prepping” to survive a global catastrophe and I was back in bunker mindset again.

Peak oil theory of collapse was pretty big at that time (there was in fact a very disturbing and moving documentary called “Collapse,” made about the top peak oil (conspiracy) theorist who later went on to commit suicide). I became convinced that all of the oil in the world was about to run out, and that there was going to be an international resource war as societies built on oil went into violent collapse. I was deeply moved by the peak oil theorist (Michael Ruppert) bursting into tears on the video when he said that when the peak oil crisis struck, society would regress to pre-industrialised living and hence pre-industrial era population levels. “Two thirds of the population will be surplus to the carrying capacity of the planet,” he said. In other words, when the oil runs out five billion people will die.

He seemed convincing, or at least his fear seemed genuine.

My wife joined me in my panic and we scouted, found, and bought a tiny rural cottage an hour and a half from the city by the side of a Scottish loch. If peak oil was coming we had to be ready and prepped: As the old doomsday prepper phrase goes “I’d rather prep 10 years too early than be 10 minutes too late.” We bought four prepper manuals and two home doctor manuals; we started trying to grow our own organic food from heritage and heirloom seeds, and watched endless prepper self-subsistence tutorials on YouTube. I filled shelves with canned tuna, beans, and pulses and created a stash of medicine, toilet roll, and diesel.

I wasn’t really aware at the time that I was subconsciously repeating myself, enacting a childhood trauma, or that I’d dragged my wife into what might be considered a folie à deux (madness for two). Our intense prepping period lasted about a year and a half. Our first crop was pathetic; after a year of nurturing our root vegetables we had barely enough edible veg for a week of roasting. Our rocket plants were the only thing that worked, so we had great bourgeois salads but no staples. We abandoned our plans to excavate under the floor to create a hidden food bunker and we ended up using up the supplies that I’d stashed. We became rather depressed and then despondent that we were overwhelmingly dependent upon shops, products “Made in China” and Amazon Prime deliveries. The deeper we got into storing and stashing, the more we’d read in the manuals that our next priority was “security” and that meant weapons. There is no point in having a stash of 300 cans of Heinz beans if you can’t safeguard them from starving looters, rioters, and neighbours. The horrible idea that we might have to fend off our rural neighbours with make-shift kitchen knives, seemed to us, one step too far. We didn’t want to hurt anyone. We were pacifists after all. We’d failed the American-style prepper lifestyle test.

There was also mounting evidence too, by 2016, that the peak oil apocalypse was not coming anytime soon. Beyond that, stepping outside our hideaway cottage the evidence was all around us that I was reliving some paranoid childhood fantasy.

Our remote location wasn’t so remote at all. In fact, it was only four miles from RNAD Coulport (Royal National Armaments Depot) and 10 miles from RNAD Faslane. Our little cottage was actually right between the two of the largest caches of nuclear weapons in Europe. Weekly a nuclear sub would sail past our window with nine missiles each with 12 warheads, each more powerful than the bomb that fell on Hiroshima. After the initial shock, I even came to find the subs quite beautiful. “They look like whales” my wife once said. If we had intended to get away from the end of the world, we couldn’t really have picked a worse place. It was as if I’d subconsciously selected a place to reinforce or finally put to rest my childhood nuclear Armageddon phobia. Bunker Boy was back.

By 2017, we’d given up on prepping and my therapist had convinced me that “catastrophising” was a problem I had to work on, to finally get over my “persecution complex.” I instead turned it all into a fiction, a novel called How to Survive Everything; it’s a story about some very paranoid preppers.

I came to see that, yes, some part of me had been secretly taking solace in end of the world fantasies for too long. By 2018, I told myself that I was done with civilisation collapses, conspiracy theories, bunkers, and lockdowns for good. Then 2020 happened.

The rest, as they say, is history. And history likes to have a little laugh at us.

When COVID-19 struck, I had this strange sense that the Western world was now being inducted into the same apocalypse mindset that I’d tried so hard to shake off. The New York Times announced “Now everyone’s a prepper” and my formerly marginal behaviour became very much mainstream. All the world wanted to be Bunker Boy, all of a sudden.

My wife and I secreted ourselves away in our failed prepper retreat, but I remained cautiously sceptical of the panic, boring everyone who knew me with my daily tally of infections and deaths, calculating degrees of safety, most of all not panicking.

As we slowly come out of what might be the final COVID-19 lockdown, it looks like we’ve somehow managed to survive yet another event that only a year ago we feared would be an apocalypse. I now look back over the decades and consider the six predicted apocalypses I’ve lived through beginning with that first nuclear Armageddon; there was global cooling, the population explosion time bomb, the AIDS pandemic, Y2K, and even the Mayan Calendar end of the world in 2012. I can only conclude that we seem to have an uncanny knack for surviving doomsdays that we’ve wrongly predicted.

All this makes me wonder if it is psychologically healthy for our societies to keep on framing events as the imminent end of the world. If everyone is now a prepper, as the NYT claims, then we are in danger of breeding a generation of paranoid, terrified bunker children who are trapped, for decades, as I was, in the apocalypse mindset.