Activism

Accommodating Trans Athletes Without Rejecting the Reality of Human Biology

As recent studies have shown, these advantages generally don’t go away simply because an athlete has changed their pronouns and hormone chemistry. At the highest levels, the difference between male and female world records typically hovers around 10 percent.

“As a social psychologist, I understand why using women’s sports to argue against transgender rights works,” tweeted behavioral scientist Matt Wallaert this week. “But it is tough to imagine a more morally bankrupt position: ‘I’m going to make you sit in a gender that doesn’t fit you so my daughter can win her soccer game.’”

And when that tweet predictably attracted scathing criticism, he doubled down on his claim that women need to do their part in accommodating trans rights by becoming more graceful losers: “This really is it: I’d rather teach my kid how to lose well than how to win through oppression.”

Walleart, best known for a Malcolm-Gladwellian 2019 business book called Start at the End: How to Build Products That Create Change, describes his approach as “a science-based process to create behavior change.” And so he offers a fitting stand-in for all the many other grandiloquent progressives who posture as rigorous scientists, even as they demand that sports leagues cast aside the plain biological reality of sexual dimorphism. The condescending, more-disappointed-than-angry tone of Wallaert’s rhetoric also is representative of a certain kind of commentator on this issue: One can almost hear him sigh wearily as he seeks to edify the hordes of soccer moms and dads who remain blinded by grubby parental vanities.

If the world’s sporting bodies were forced to choose between (a) the traditional differentiation of sports competitions along male-female lines, and (b) a system of unfettered gender self-identification, the choice would not be difficult: The idea that half the planet should focus on being a good loser while male bodies dominate the medal podium is preposterous and sexist.

From puberty onwards, male physiological advantages express themselves as increased muscle mass, higher lung capacity and blood flow, and increased bone strength. As recent studies have shown, these advantages generally don’t go away simply because an athlete has changed their pronouns and hormone chemistry. At the highest levels, the difference between male and female world records typically hovers around 10 percent. The men’s world record in the 100m dash, for instance, is 9.58 seconds. The record among women, by contrast, is 10.49 seconds—a time that is routinely bested by teenaged male athletes at high-school track meets. And so while the number of transgender women competing may still be small, their likelihood of out-competing biological females is high. And in sports that involve physical contact, such as rugby and boxing, ignoring the biological differences between men and women isn’t just unfair, but also dangerous.

Thankfully, lawmakers and sports officials aren’t confined to this (as the expression goes) false policy binary, because there are ways to protect the integrity of female athletics while also treating transgender individuals with dignity and respect. One promising option, for instance, would be to preserve the traditionally defined female category while also rebranding the male category as an “open” category that’s available to anyone. This would allow a biologically male trans woman, or someone who is intersex, to test their speed, skill, and strength in a fair competition, while also not forcing them to submit to a designation they may find inaccurate or demeaning. Once overwrought ideological claims about the nature of gender identity are stripped away, in fact, open athletic categories may even provide a forum for real diversity and universal inclusivity, which is the ostensible goal of those demanding that women compete against male bodies.

The two main impediments to implementing such an approach manifest at opposite ends of the ideological spectrum: conservatives who refuse to offer any nod to the reality of transgender individuals, and doctrinaire progressives who insist that all debate begins and ends with simple slogans or clever-seeming non sequiturs about hermaphroditism in clownfish and bog onions.

Sexual dimorphism is obviously a crucial aspect of human reproductive biology, and serves as a driver for countless important differences in the bodies of men and women. Anyone who seeks to engage productively in this debate should understand this principle, and be able to identify the various rhetorical techniques that some activists use to gaslight those who uphold it.

In this regard, it’s useful to examine the advocacy of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a venerable American non-profit organization that was founded a century ago “to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States.” While the organization still does valuable work that’s consistent with this mandate, it has, in recent years, committed itself to an extremist formulation of transgender rights that has now blurred into anti-scientific obscurantism—a campaign led by the ACLU’s Deputy Director for Transgender Justice, Chase Strangio, who has repeatedly set out his arguments in widely disseminated essays and Twitter threads that purport to “debunk” popular “myths” about trans athletes. Let us examine some of his recent claims one by one.

The first of the ACLU’s alleged “myths” is actually a series of three linked ideas—that “sex is binary,” that it’s “apparent at birth,” and that it’s “identifiable through singular biological characteristics.” This is a subject that Quillette managing editor (and PhD evolutionary biologist) Colin Wright has addressed in detail.

To summarize: As a matter of biology, the sex of an individual human refers to one of two—and only two—functional roles that an individual may play in sexual reproduction. Males are defined as the sex that produces small, motile gametes (sperm), and females produce large, sessile gametes (ova). There is no third gamete between sperm and ova, and therefore there is no third biological sex apart from male and female. Yes, there is a small portion of the population born with intersex conditions—whereby they exhibit external sex ambiguity, or a mismatch between internal sexual anatomy and external phenotype—but they do not produce unique forms of gametes, or have primary sex organs that would normally produce them, and so they do not constitute a third sex, even if, in some extremely rare cases, they can’t be definitively classified as male or female.

Nor is the sex binary at odds with the reality that many transgender individuals defy gender stereotypes through their appearance and behaviour. Sexist stereotypes are social constructs, and we are happy to see trans people smash them as they please. But they have nothing to do with determining one’s biological sex.

Because the prevalence of intersex conditions is so low, those seeking to challenge the reality of sexual dimorphism often will conflate true intersex conditions (which denote sex ambiguity or an internal-external phenotypic mismatch) with disorders/differences of sexual development (known as DSDs), a more comprehensive term that includes “any problem noted at birth in which the genitalia are atypical in relation to the chromosomes or gonads.” In fact, some even go so far as to broadly define an intersex person as “an individual who deviates from the Platonic ideal of physical dimorphism at the chromosomal, genital, gonadal, or hormonal levels,” which encompasses many individuals who are not sexually ambiguous at all, such as men with Klinefelter syndrome and women with Turner syndrome. This extreme definition is what gives us the frequently cited but grossly inflated figure of 1.7 percent for people born with intersex conditions.

But in truth, the correct figure is about 100 times smaller: only about 0.018 percent of the human population is believed to be intersex in a clinically relevant sense. And while it is true that newborns sometimes really do present doctors with classification challenges, a misclassification rate of only one in 5,500 likely places sexual development among the most reliably consistent phenomena in the life sciences.

A second “myth” that the ACLU targets is the claim that “trans athletes’ physiological characteristics provide an unfair advantage over cis [i.e., non-trans] athletes.” On this claim, the ACLU offers two related arguments: (1) All athletes, including trans athletes, vary in athletic ability, and (2) trans athletes don’t always win when they compete.

It’s absolutely true that most female athletic competitions are not won by trans athletes. But it’s hard to see how this proves anything, except the uncontroversial fact that there are still relatively few biologically male trans athletes who seek to compete against women—possibly because many of them choose to respect the boundaries of female sport on their own initiative, even when policymakers give them license to do otherwise.

In many infamous cases, unfortunately, male-bodied competitors have completely crushed their female rivals once they have switched over to female athletics—as with the case of transgender hurdler CeCe Telfer, who ran as an unknown men’s track and field hurdler for three years in college before utterly destroying the field in a 2019 NCAA competition. In one case, a middle-aged trans woman beat out biological women half her age. In another case, a 52-year old trans woman played on her college basketball team. If biology were immaterial, then where are the middle-aged biological women dominating male weightlifting competitions, winning tip-offs in male basketball leagues, and crushing men’s skulls in the boxing ring?

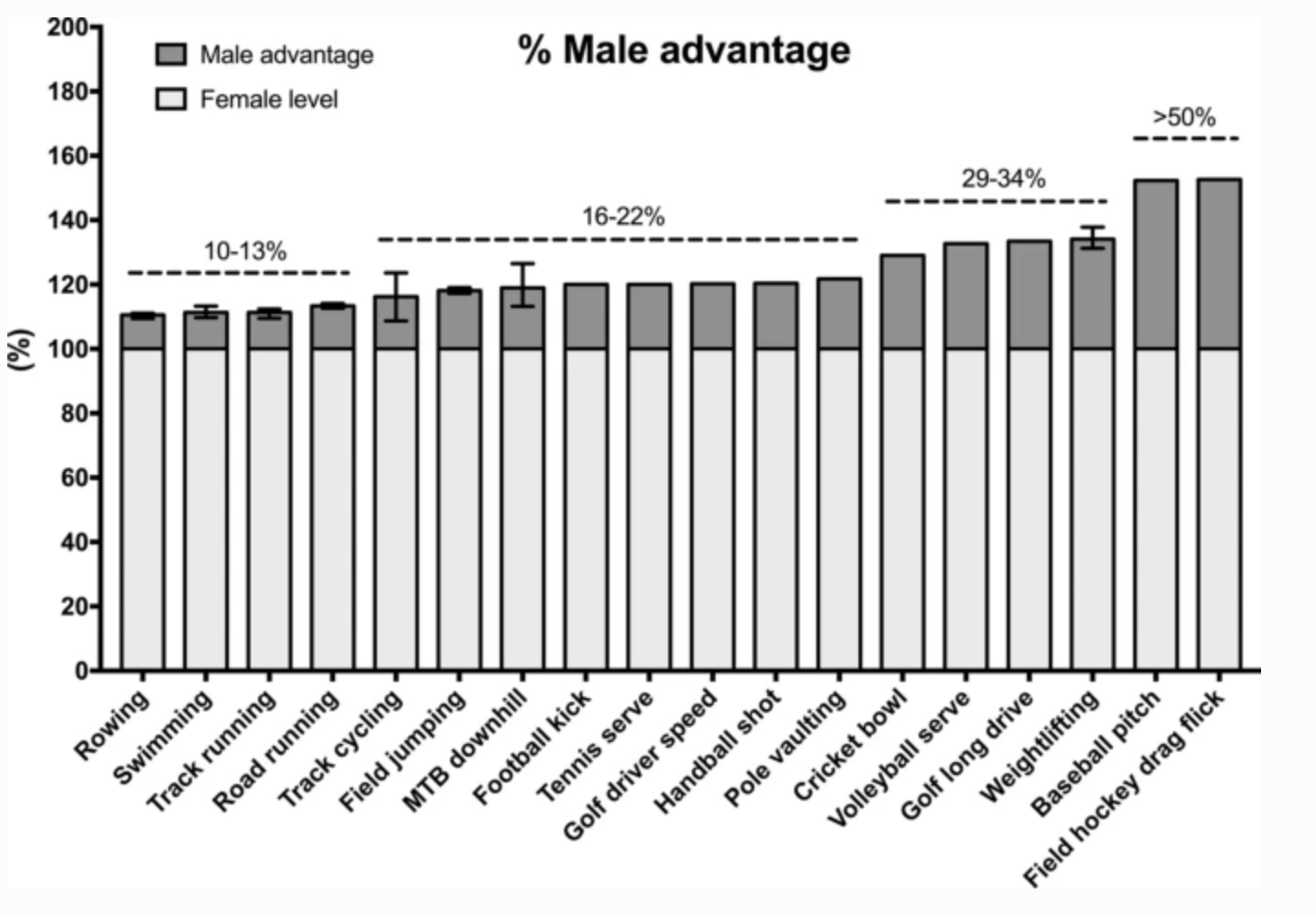

Those seeking the answer may refer to the 2020 Sports Medicine article ‘Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage,’ in which Drs. Emma N. Hilton and Tommy R. Lundberg examined the performance gaps between men and women in 18 different sports. They found that:

the smallest performance gaps were seen in rowing, swimming and running (11–13%) [relative to female baseline], with low variation across individual events within each of those categories. The performance gap increases to an average of 16% in track cycling, with higher variation across events (from 9% in the 4000m team pursuit to 24% in the flying 500m time trial). The average performance gap is 18% in jumping events (long jump, high jump, and triple jump). Performance differences larger than 20% are generally present when considering sports and activities that involve extensive upper body contributions. The gap between fastest recorded tennis serve is 20%, while the gaps between fastest recorded baseball pitches and field hockey drag flicks exceed 50%.

Of course, the distribution curves between males and females for athletically-relevant traits such as size, speed, and strength do overlap‚ as every person of ordinary common sense knows. Unless we happen to have a disproportionately large number of professional male athletes among our Quillette readership, for instance, we’re guessing there isn’t a man reading this who could take a point off Serena Williams on a tennis court. In the same way, there are many teenagers who can outclass most full-grown adults in all the sports we’ve mentioned, yet no one is proposing to eliminate age distinctions in sports.

Moreover, as Drs. Hilton and Lundberg concluded,

even after testosterone suppression, the performance gap between males and females is only minimally reduced. The data presented here demonstrate that superior anthropometric, muscle mass and strength parameters achieved by males at puberty, and underpinning a considerable portion of the male performance advantage over females, are not removed by the current regimen of testosterone suppression permitting participation of transgender women in female sports categories. Rather, it appears that the male performance advantage remains substantial.

The third “myth” that the ACLU purports to have debunked is the claim that “the participation of trans athletes hurts cis [i.e., biological] women.” Unlike the first two entries, which relate to scientific ideas, this one advances a moral claim about harm.

There is a grain of truth to the ACLU’s claim that some sex-determination procedures for intersex athletes are invasive, and require reform. But it is difficult to consider the ACLU a good-faith actor on the issue of harm more broadly, given that the organization’s own staff have argued that legislation aimed at protecting the integrity of girls’ athletics cannot be motivated by anything except “fear mongering intended to push transgender and non-binary people out of public spaces.” It’s easy to win an argument about “harm” if you falsely claim that your opponents are malevolent bigots seeking to increase harm rather than alleviate it.

The soft version of the ACLU’s argument, provided by Wallaert, is that women will actually benefit from the inclusion of more male bodies in their sports because the experience of consistently losing will build character. One also hears vaguer versions of this idea put forward, to the effect that sports shouldn’t really be about winning and losing at all, but rather about inclusion and participation—a sunny-sounding proposition that, while workable at the level of amateur participation sports, has little relevance to the factors that push competitive, high-level athletes to pursue excellence. And the same people who insist that women should make room for male bodies, even at the expense of destroying their own chances of victory, would likely be horrified if professional male sports leagues stopped keeping score, or if the Olympics stopped awarding medals but rather ended every competition with a group hug.

The final “myth,” that “trans students need separate teams,” seems to be really just a pretext for Strangio to argue that paying heed to the biological differences between men and women may cause trans people to “experience detrimental effects to their physical and emotional well-being,” and so deprive them of “caring environments where teammates are supported.”

It’s absolutely true that trans people often suffer when they experience dissonance between their internally felt gender identity and sex in certain contexts in the world around them, including in the realm of sports. But in the long run, it won’t do them much good to put that dissonance on display in front of thousands of sports spectators, even as part of a well-intentioned policy of inclusion.

Times being what they are, most journalists do feel compelled to sing from the ACLU hymn book when it comes to celebrating the accomplishments of trans athletes. (Outsports magazine even made the ludicrous claim that Fallon Fox—a male-bodied MMA fighter who’s cracked the skulls of two female opponents—is the “bravest athlete in history.”) But ordinary sports fans aren’t so easily duped, and trans athletes have complained that crowds sometimes fall silent, or even express disapproval when they achieve their victories. In many cases, the backlash has been intense. The ACLU can debunk all the “myths” it pleases, but sports fans know what’s fair and what isn’t. Nothing Strangio writes will change that.

The most humane way to help and support transgender people isn’t to pretend that slogans and hashtags will magically transform them into something they’re not. It’s fine to say that “trans women are women,” full stop, as a matter of certain legal entitlements. But biology doesn’t care about what pronouns we use. And trans athletes shouldn’t be encouraged to inhabit a state of denial. There are creative strategies we can implement to invite, and even celebrate, the participation of trans athletes in all sports. But they can be implemented only once we admit the real differences that exist between the two—and only two—sexes.

Featured image: Trans athlete Laurel Hubbard at the 2019 World Weightlifting Championships.