History

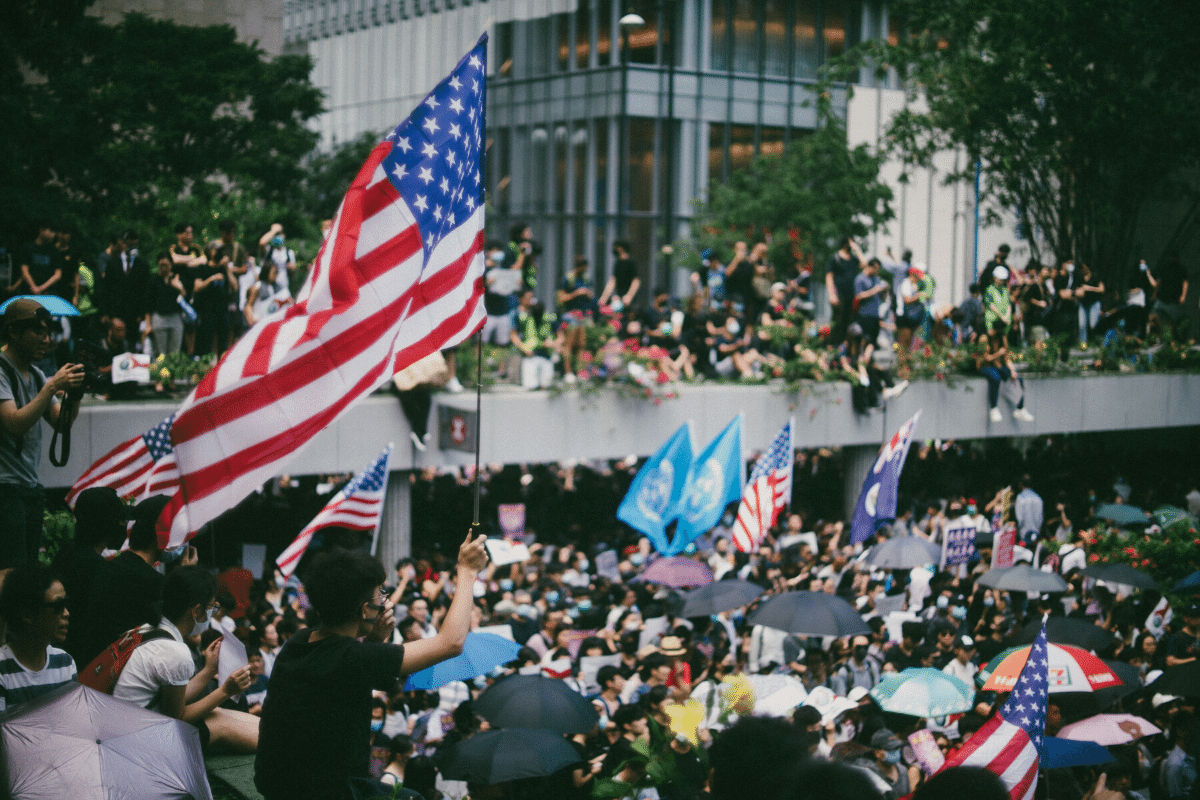

Dictatorship and Responsibility in Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s political culture is being dismantled.

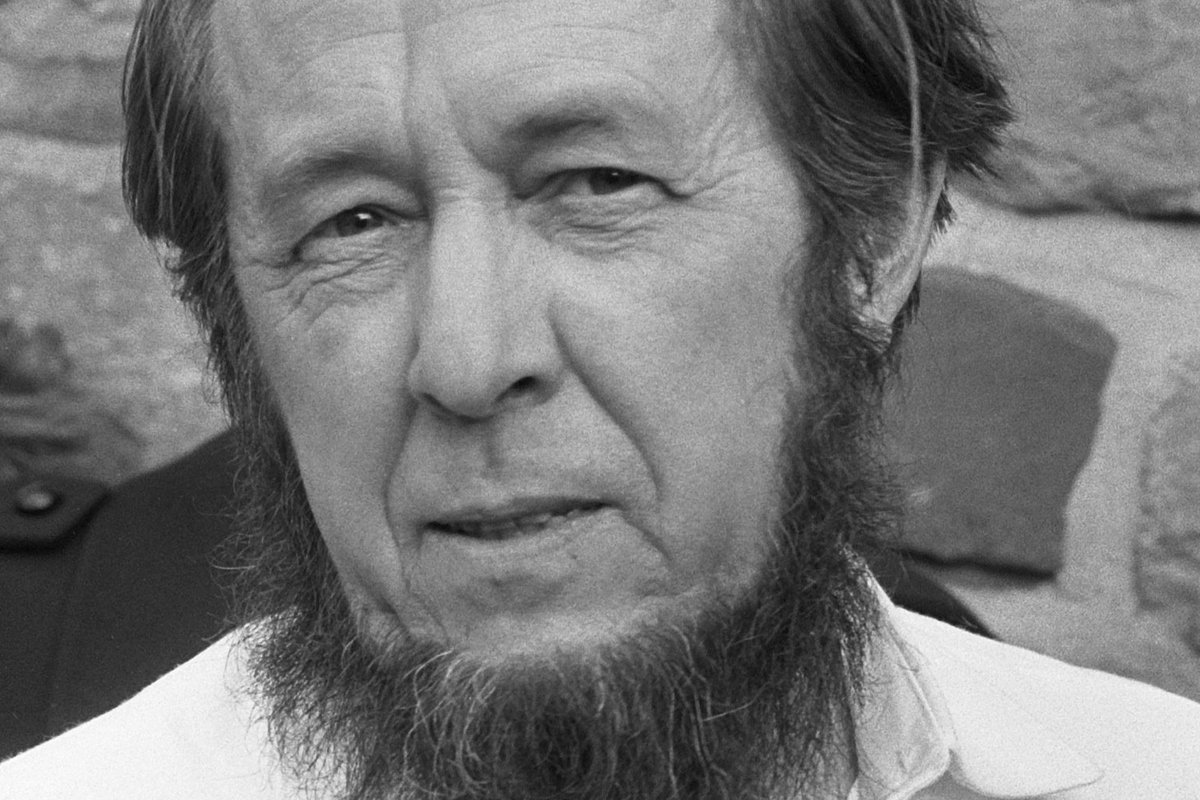

Thus, the population was shaken up, forced into silence, and left without any possible leaders of resistance. So it was that ‘wisdom’ was instilled, that former ties and friendships were cut off.

~Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (1985).

I

Can moral life survive dictatorship? When a government intimidates its subjects; when it sows mistrust among them; when it penalizes virtue and incentivizes servility, how might men and women keep faith with themselves and their fellows? Citizens of democratic states tend to ponder such questions, if at all, with a detached, even theoretical, interest. Dictatorships happened then or, if extant, occur over there. But in the once-free city of Hong Kong such insouciance has vanished.

For just over two decades Hong Kong lived the life of an anomaly. When Britain, in July 1997, renounced sovereign rule over Hong Kong, the colony became a “Special Administrative Region” of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Under the terms of the Sino-British Declaration (1984) and the articles of the Basic Law (adopted by the National People’s Congress in 1990), Hong Kong was entitled to retain its civil and political freedoms, and its free-market economy, till July 2047. “One country, two systems,” “Hong Kong people governing Hong Kong,” and “high degree of autonomy” were the slogans that defined the city’s special status in the PRC.

Today, they sound farcical. On June 30th, 2020, a national security law was imposed on Hong Kong by Beijing; its spongy, catch-all articles criminalize whatever the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) brands as secession, subversion, terrorist acts, and collusion with hostile foreign powers. The reach of the law is global or, in legal jargon, extra-territorial, meaning that actions that are legally permitted in one national jurisdiction (say, Canada or Australia) may be criminal in Hong Kong and punishable there. Hong Kong people who live abroad are thereby served notice that the CCP is watching and that those who criticize Chinese Communism in a foreign country had better be prepared for permanent exile or arrest upon return home.

II

I will not log the details of Hong Kong’s national security crackdown. Locals know them all too well and, for others, monthly updates are available courtesy of the Hong Kong Free Press (start here). My subject is the potential of Hongkongers to remain self-respecting, self-possessed moral agents in the new order. Precisely because their situation is not without precedent, recalling how others withstood dictatorship may help Hong Kong people endure it too.

In 1964, America’s foremost theorist of totalitarianism, the political writer Hannah Arendt, gave a talk on the BBC called “Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship.”1 Its gist was this: children obey, adults consent. What is called obedience in the political realm is no such thing: it is tacit or express support for a program, a leader, a party. Sifting obedience from the vocabulary of moral and political thought would not only help clarify the meaning of our actions. It would also, said Arendt, restore “what former times called the dignity or the honor of man.”

Witness-critics concur—I shall come to their testimony in a moment—that responsibility under dictatorship has at least two dimensions: a responsibility to do no harm to others, and a responsibility to be honest with oneself. In the first case, responsibility turns on restraint; on refraining from any action that fortifies the regime or weakens others subject to its domination: actions like informing on a neighbour, bearing false witness, signing a questionable document, colluding in the unjust demotion of a colleague, or opportunistically ingratiating oneself with a power-holder. A related responsibility is to provide solace to those in close proximity who are embattled and humiliated by the regime. For of the many ills caused by dictatorships, the loss of human fellowship—isolation—is among the worst. Sometimes a simple glance of encouragement, a shared joke, a hand-shake, or another courteous greeting is enough to signal to someone marked as a regime pariah that they are still valued members of a human community.

But individuals also have responsibilities to themselves under dictatorship, and these turn on a constant, ever-renewed commitment to the principles of truthfulness: interpersonal truthfulness—minimally, a refusal to repeat and spread the regime’s lies—and intrapersonal truthfulness—essentially, a refusal to lie to oneself. Remaining truthful in both senses requires something more than clarity or acumen. It requires sustained alertness and effort: the willful, deliberate exercise of human conscience to recognize and name, if only under one’s breath, and to oppose, in whatever way possible, what is evil. Being truthful is taxing under the best of conditions. Is it really possible under the worst? Witness-critics of dictatorship show that it is.

Obligations to ourselves and to others under dictatorship are connected. The more we are truthful to facts and to ourselves, aware of what we are doing, and willing to act accordingly, the less likely it is that we will do harm to others.

III

Dictatorships in general—and totalitarian states in the grip of National Socialism and Communism in particular—are remarkable laboratories in which to observe the workings of human obfuscation. Not all ruses are equally effective, however. One might think that dictatorships, with ample resources of propaganda, would find it easy to mislead their subjects. Not always. The reason is that states, desiring legitimacy among their own subjects, as well as among the international bodies with whom they interact, profess their standards in official formats: laws, constitutions, international protocols. When those standards are visibly breached in practice, as they regularly are, the authority of their agents erodes.

By contrast, individuals are far more adept than states at covering their moral tracks. Whereas dictatorships try but often fail to fool their subjects, individuals prove to be geniuses at fooling themselves.

In 2009, Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was imprisoned in China for the crime of “incitement to subvert state power” (to quote the verdict of Beijing No.1 Intermediate People’s Court Criminal Judgment No. 3901). And what did this incitement consist of? “Liu Xiaobo took advantage of the media characteristics of the Internet [and] exceeded the scope of freedom of speech.” Decoded, Liu signed, sponsored, and transmitted Charter 08 whose first principle is civic and political freedom; the charter calls liberty “the core of universal human values.” Officially, Article 35 of the PRC constitution guarantees “freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and demonstration.” Not so, Liu’s charter declares: “The political reality which is plain for anyone to see is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government.”2

A similar note is sounded by the blind lawyer Chen Guangcheng who, following his own serial harassment and arrest, escaped to the United States. Recounting village life in Shandong province, Chen writes that “by the late 1980s, no one believed in the annual propaganda anymore.” His tobacco farming family had witnessed party officials claim, at market, that the leaves, being of low quality, were worth a pittance, only later to discover that the same officials were selling the tobacco at a considerable mark-up. “The ruse was transparent,” laments Chen. And the message was clear: “you simply couldn’t trust the government with your basic survival.”3

Article 38 of the PRC Constitution guarantees the “dignity” and “inviolability” of citizens. Yet “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble,” in Communist Party gibberish, was enough for a mainland critic of Hong Kong’s national security law, Zhang Wuzhou, to find herself in police custody, her body contorted into a human ball, hands and feet tied together in metal cuffs. “Picking quarrels and stirring up trouble” also felled the mainland citizen-journalist, Zhang Zhan, who reported on the CCP’s botched handling of COVID-19 in Wuhan. Serving a four-year sentence, she is currently on hunger strike.

In all such cases, a state’s deception and double-standards are, paradoxically, all too obvious. “Plain for anyone to see.” The constitution says one thing; the authorities do another. By contrast, the deception practiced by individuals on themselves—self-deception—is not obvious; it is all too murky. The shrewdest account of it I know comes not from a Chinese thinker, however, but from a German one: Karl Jaspers, a prominent psychologist and philosopher who lived through the Nazi years. He was forced to resign from his post at the University of Heidelberg in 1937 because of the taint attached to his having married a German-Jew. Miraculously, Jaspers and his wife Gertrud survived the war physically unharmed, not actively opposing the Nazi state but, going into “inner emigration,” refusing to collaborate with it in any way. When the war ended, Jaspers urged his fellow Germans to take responsibility for the many ways in which they had supported and participated in a genocidal regime. Though he was writing specifically about Germany under National Socialism, Jaspers’s analysis applies to conduct under dictatorships more generally.

A striking feature of Jaspers’s moral perspective is his refusal to portray German citizens as benighted or ideologically saturated people, incapable of understanding their circumstances in a realistic light. And it was precisely this refusal that drove him to coin the concept of “false conscience” (falsches Gewissen) as a counterpoint to the Marxist idea of “false consciousness” (falsches Bewusstsein). Jaspers did so in his book Die Schuldfrage (1947), published in English a year later as The Question of German Guilt. Admittedly, “false conscience” is an odd-looking idiom, at least in English. But Jaspers had good reasons to coin it.

To describe participation in the Nazi Reich as evidence of “false consciousness,” as Marxists did, or as a manifestation of an “authoritarian personality,” as Marxist-Freudians did, actually suggests that no moral culpability can reasonably be attributed. After all, if a consciousness is false and then later becomes true, persons gifted with this miraculous transformation are essentially bifurcated beings. Only their true consciousness can (now) be morally appraised. Their former false consciousness cannot for it was determined by economic circumstances, “geographical conditions,” “world-historical situation” and the tempestuous forces unleashed by Nazi rule. Similarly, individuals subject to an authoritarian upbringing can hardly be responsible for its impact on their “personality.”

As soon as one speaks about false conscience, however, an entirely different being is evoked. This being, possessed of a memory, has coherence as a person. No longer split into a before and after, the human being in 1945 bears continuity of personhood with who they were and what they did in 1944, 1941, 1939, 1938, and 1933. Possessing a will, this being continues to have, as they have always had, choices, even if some were infinitesimally small. Was it really necessary to spout Nazi slogans in situations where no one forced you to do so? Were all those Nazi salutes to the Führer really required, when your coworkers saluted more rarely and some not at all? Were you really compelled to cross the street to avoid greeting a frightened Jewish neighbor with whom you had previously exchanged pleasantries? Possessing a conscience, the individual has the ability to feel as well as think; to grasp degrees of right and wrong; to monitor forms and degrees of participation in the regime. Possessing a conscience, persons can resolve to live in harmony with themselves and uphold standards of decency in their relations with others. Evidence that conscience can actually become false, and is not merely an ideological vector, lies precisely in the skillful maneuvers that humans deploy to deny they are actors with choices to make or avoid making.

Jaspers believed that almost everyone in Germany, including himself, was guilty to some degree of moral wrong. It was not Germans as a collective subject, not Germany, that had been fooled and that subsequently, in distortions of memory, fooled itself. It was German individuals—a Herr Hoffmann, a Frau Koch and millions of others with names, friends, and families—who had cooperated with the Nazi regime, and each of their stories was different. Denying responsibility, evading the chance later to make amends, refusing to reappraise one’s life and, instead, blaming others or making excuses: this was false conscience. As such, it does not fall within the jurisdiction of the courts or political tribunals but within the province of personal morality. Preventing or correcting it must take place at the individual level; for only individuals have the freedom to change their opinions, to admit or distort observation and memory. Loving friends can help a person accept responsibility, change, and attempt to repair. Didactic utterances and lectures cannot. Repeatedly, Jaspers calls for “self-analysis,” “self-judgment,” and individual “exertion.” He pleads with fellow Germans to make distinctions in the pursuit of truth and avoid distinctions designed to evade it. His appeals are credible to souls weighed down by false conscience. They would be meaningless to addressees of false consciousness.

Another writer to reject the Marxist notion of false consciousness was Václav Havel, the Czech playwright, essayist, and dissident who later became president of Czechoslovakia and then president of the Czech Republic. When Jaspers in 1947 traced the moral conduct of fellow Germans under National Socialism, the regime he described was already extinguished. Havel’s focus—in his essay “The Power of the Powerless” (1978)—was on the behaviour of fellow Czechs under Communism, a regime still intact at the time of his writing. Instead of invoking false conscience, as Jaspers had, Havel returned to the more familiar term “ideology.” But he then reshaped its meaning.

Ideology, for Havel, is not, as it is for Marxists, a mystification of reality created by the commodity form, a puzzle that only the truly enlightened—Marxist intellectuals!—can crack. Ideology, in Havel’s usage, is eminently accessible; it is a system of rules and rituals initiated by the regime but in which citizens voluntarily participate. They do so because it takes less effort to go along with a repressive system than to admit to oneself, let alone to others, that it is a generator of outright lies: for instance, the lie that Communist governments respect human rights and are committed to peace; the lie that Communism represents the will of the people. While behaving like automata, many Czechs are simultaneously aware, at some gnawing level, that they are free to think and act as persons who prefer truth to lies, and that they can only feel themselves to be vigorously whole persons if they behave honestly. The result of consenting participation in the lies and rituals of an ideological system is cynicism and apathy, the loss of meaningful human connection—in short, a corrupted soul.

Living in truth, Havel declares, is an “existential” condition far more than a “conceptual” one. It requires practical, frank reckoning, not abstruse theory. (Jaspers had made the same point.) The fruit of living truthfully is not a utopian dreamscape, but the restoration of dignity and solidarity. And this is something for which everyone might strive, so long as they are willing to stop repeating the deceits, and performing the rituals, that reproduce the Communist regime. The subjects of the regime “are both victims of the system and its instruments,” both “victims and supporters,” insists Havel. Accordingly, once they withdraw their consent by refusing to live a lie, however small that lie is, the whole regime is threatened. For Communism is built on falsehoods and unravels one truth at a time.

The Russian novelist and Gulag inmate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had arrived at the same conclusion in “Live Not by Lies,” a biting condemnation of Soviet Communism released on the day of his arrest on February 12th, 1974. Solzhenitsyn’s essay is not a philosophical tract or a work of art. It is a blunt reproach to passivity and cowardice. To be sure, “we are not called upon to step out onto the square and shout out the truth, to say out loud what we think,” admits Solzhenitsyn. Nor are we morally obliged to disregard the safety of our family. But are we then prepared to raise children “in the spirit of lies,” or encourage them to grow up to resemble placid cattle? In a check-list of self-imposed prohibitions, Solzhenitsyn counsels his contemporaries to adopt the following pledges: never to write, sign, or publish a single line that appears to distort the truth; never to take part in a regime-orchestrated rally unless forced to do so; never to raise one’s hanhttps://quillette.com/2023/08/24/the-chinese-exodus/d to vote for a proposal that is obviously a sham.

Elsewhere, Solzhenitsyn remarked: “Let him not brag of progressive views, boast of his status as an academician or as a recognized artist, a distinguished citizen” if such a person willfully forgets or obscures truthfulness. And for the authorities, Solzhenitsyn had a warning: that the hour will come “when each of you will seek to scratch out your signature from under today’s resolution.”4

It is startling to recall that “seeking truth from facts”—shishi qiushi—was a Maoist slogan of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. It is still popular in China today, favoured by President Xi Jinping, and compressed in the title of Qiushi Journal, an important policy and theory organ of the CCP. (Pravda, the official paper of the old Soviet Communist Party, also means “truth.”) But according to Maoist doctrine, truth is not to be pursued, as it is in empirical science, through open and disinterested enquiry, and its results reported without fear or favour. Truth is Marxist ideology. Facts are what the party calls them, makes them. As the sinister Kang Sheng, one of Mao’s lieutenants, explained to cadres of the Case Examination Group (a unit charged with the violent purging of all whom Mao deemed enemies of the proletariat), seeking truth from facts is a mode of investigation that requires, first, “a firm grasp of the Chairman’s Thought”; second, a “correct… class viewpoint” that “must never, not for a minute, waver”; and third, “a firm grasp and command of (CCP) policy.” “Case examination work is difficult and strenuous,” the master interrogator solicitously grants. Cadres must never drop their guard. China teems with Soviet, Korean, and Mongolian “revisionists,” undoubtedly in cahoots with Japanese and Guomindang (Taiwanese) “spies.”5 Failure to unmask them, preferably in batches, is evidence not of the absence of malcontents but of the incompetence of investigators.

IV

The untaught lesson of post-colonial studies is that Hong Kong, precisely because it was a British colony, escaped the depravities of the Maoist era: mass shootings of so-called feudal landlords; forced collectivization of the peasantry, cadre-purge without cease, yundong (ideological campaign), “struggle sessions,” engineered mass starvation, the Cultural Revolution, and much more besides. The PRC was founded in 1949. Between 1950 and 1979 around two million mainland Chinese fled to Hong Kong seeking security and freedom.

Those conditions no longer exist. Hong Kong’s pan-city Legislative Council elections, which were due to take place in September 2020, were suspended, and a group of democratic lawmakers ousted from office. (In solidarity, but also with a growing sense of impotence, their colleagues resigned en masse.) Pods of oppositionists are arrested weekly, 53 in a single morning (January 6th, 2021). Civic groups are disbanding, relocating their computer servers abroad, and scrubbing the names of volunteers and sponsors. Famed figures of the democracy movement, and many others unknown to an international audience, are imprisoned; they include Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow and Jimmy Lai. The national security department, and particularly, its security police, is now in control of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s political culture is being dismantled as well. Public libraries no longer stock books by pro-democracy advocates, and booksellers are skittish about selling them. School teachers are instructed in Communist pedagogy, euphemistically called “patriotic” education. A National Security Hotline is available for Hongkongers to inform on colleagues, neighbors, and sundry others who utter an incautious phrase. University professors are sacked and denounced, and university students are reported by university managements to the police if democracy slogans (such as “Reclaim Hong Kong. Revolution of Our Times”) are voiced on campus. Independent reporting is also under siege, evidenced in the police invasion of democracy tabloid Apple Daily’s headquarters, the arrest of Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK) freelance producer Bao Choy, and the firing of an elite investigative journalist team at i-Cable’s news department. It is only a matter of time before international media join the New York Times in decamping from Hong Kong to Seoul or to Tokyo for a new base of operations.

It seemed comically redundant when, in November 2020, Beijing announced its plans for “comprehensive governance” over Hong Kong—effectively direct rule by the Communist Party. For such supervision of the city’s affairs is already obvious. Hong Kong Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, is city leader in name only. A career civil servant, who has never stood for a citizen election, Lam is the monotonic mouthpiece of Beijing. “Aggressive, cold-hearted, and stubborn” is how one local assessed her character to me recently. The young man’s tone was cool and resigned, not bitter, almost as if Lam ruled from a station on the Moon.

***

A foreigner nearing retirement age like me, who plans to return to his home country, is in no position to advise Hongkongers on how to prepare for the years ahead. Only those who remain in the city have the moral right to guide it. Besides, survival under dictatorship is a process of learning and improvisation; no blueprint exists or can exist to map the contingencies that time and chance drop in the laps of human beings. I have written this essay, then, simply to call attention to the record left by others who struggled to survive liberty-crushing regimes with their self-worth intact. A scholar of such regimes, I offer this comparative perspective in a spirit of encouragement.

How long will Communism’s debasement of a great city last? How will it end? We cannot know. But we do know, from the recorded experience of other oppressed peoples, that Hongkongers are not destined to become Communist drones, mouthers of ideological claptrap and interchangeable parts of a uniformly dominated machine.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Judith Alder for her comments on this essay and, even more, for her willingness to think through with me the problems the essay tackles.

References:

1 Hannah Arendt, “Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship,” in Responsibility and Judgment, edited by Jerome Kohn. New York: Schocken, 2003, pp.17-48.

2 Liu Xiaobo, “Charter 08,” in No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems, edited by Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, and Liu Xia. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2012, pp.303-305.

3 Chen Guangcheng, The Barefoot Lawyer. New York: Henry Holt, 2015, pp.50-51.

4 “Open Letter to the Secretariat of the RSFSR Writers’ Union,” in The Solzhenitsyn Reader: New and Essential Writings 1947-2005, edited by Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney. Wilmingon, DE: ISI Books, 2008, pp.509-11.

5 Kang Sheng, “On Case Examination Work,” (April 1968) in Michael Schoenhals (editor and translator), China’s Cultural Revolution. Not a Dinner Party. Armonk, New York: Sharpe, 1996, pp.116-122.

Photo by Joseph Chan on Unsplash