Top Stories

Songs from Orwell's Glass Asylum

Bowie’s album beautifully captures the essential romance in the story.

In 1947, the year David Bowie was born, a tubercular George Orwell shuffled over to the bedroom window of his cottage on the storm-lashed Scottish island of Jura and thought about London. He was always thinking about London. The ailing Orwell—moustache and cigarette drooped downward, clad most of his days in just the same old raggedy dressing gown as he propped himself up in bed with a typewriter—was in a race against time to polish off the manuscript of what would be his ninth and final book, Nineteen Eighty-Four, a dystopian satire about totalitarianism and the cynical manipulation of language set in the British capital in the not-too-distant future.

Orwell later said that the book was about his fear that “the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world.” This he fleshes out by way of a doomed romance between Winston Smith, a wavering individualist who has begun to doubt the wisdom of the media that ceaselessly broadcasts the Party’s bizarre slogans, and a freckle-faced young sensualist named Julia. Both characters meet a rather sticky end.

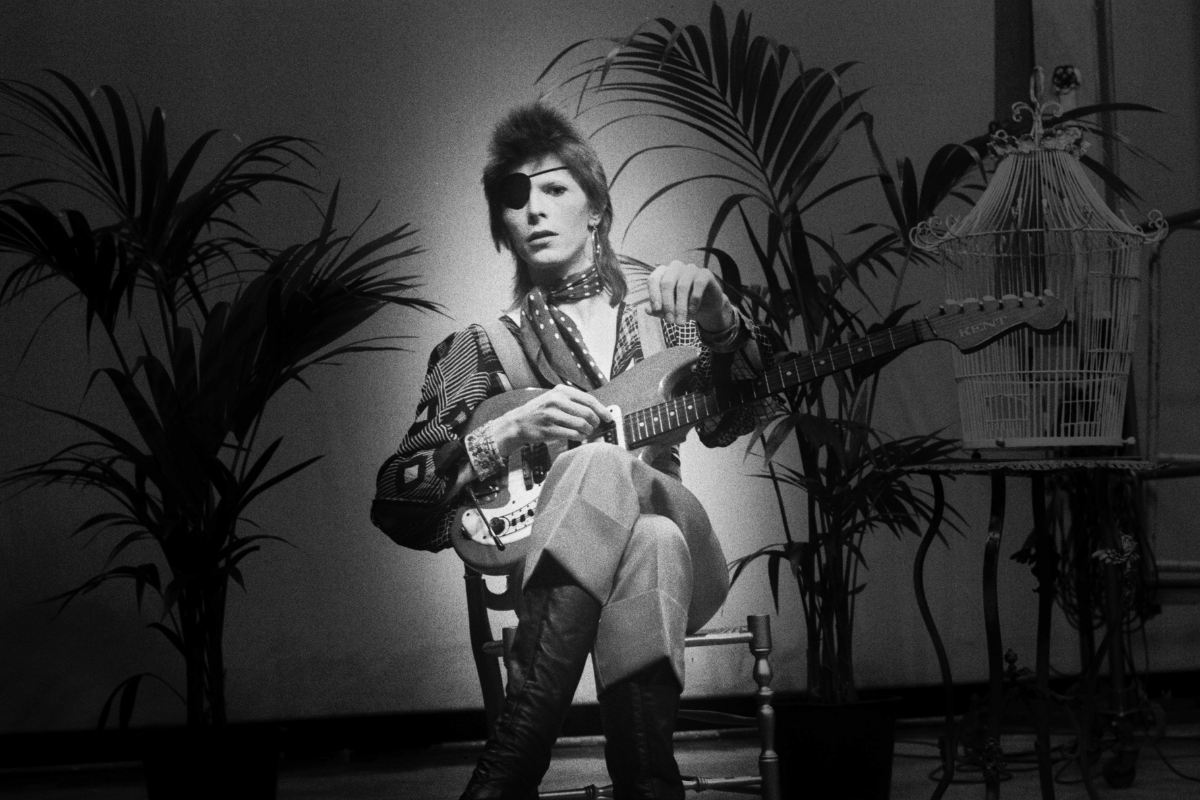

A couple of decades on, it was David Bowie—snakehipped, orange coxcomb hair, all heavily made-up mismatched eyes and crooked teeth—at his window in London thinking about George Orwell. He was always thinking about Orwell. The flamboyant young singer-songwriter-composer was among the first significant younger cultural figures to become captivated by Orwell’s work. Bowie not only recognised the book’s literary beauty and social relevance but intuited its gigantic musical opportunity. At some point—we don’t know precisely when—he scratched out a couple of lines that serve as the lyrical drumroll for the new album:

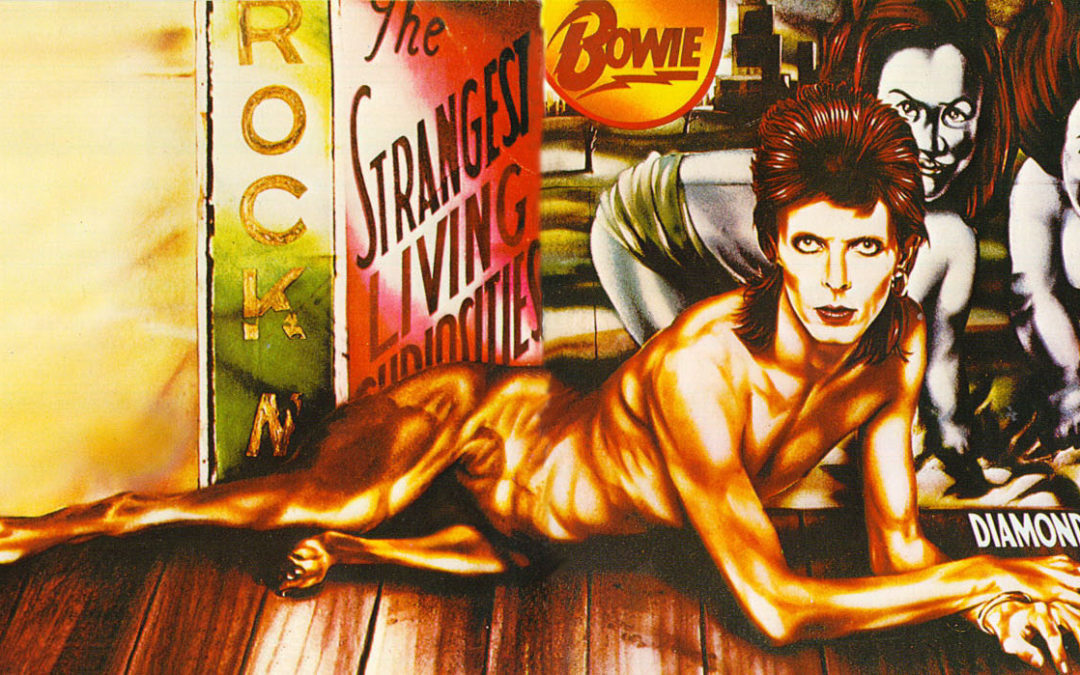

This ain’t rock’n’roll.

This is… GENOCIDE!

So began the unlikeliest of intergenerational collaborations on Bowie’s eighth album of original material. Diamond Dogs was released a few months after his 27th birthday in May 1974, and remains as appealing today as it first did nearly a half-century ago. Certainly, the music—the desperately ecstatic ballads, the scrungy proto-punk stuff, the three-dimensional song suites—is still startling enough to justify a red carpet on the fifth anniversary of its creator’s death.

Not to mention the relevance of it all: the locked-down city whose inhabitants are succumbing to some kind of mysterious plague; the zombie kids staggering along the streets glued to little “telescreens” that not only send and receive messages but also keep tabs on their users at all times; and, especially, I think, the oppressive culture in which language is forever being squeezed and even the favourable mention of biological sex is capable of igniting a riot. The themes of the music, like the book that inspired it, are generally unpleasant, but it’s exhilarating too, because it’s filled with yearning and passion, and you keep on hoping things might get better… but hope, boys, is a cheap thing.

What a partnership. Collaborations are nothing new in rock and pop. Many enduring works have been forged from the collision of disparate talents, from the classic rock playlists (Jagger-Richards, Lennon-McCartney, Cale-Reed), or producer-artist pairings such as Al Green and Willie Mitchell, or acts a little closer to the current era, like, oh, I don’t know, Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. But these tend to be musical partnerships. Bowie enjoyed a few of those, too, with players like Mick Ronson and Mike Garson, his short-term guitarist and long-term avant-garde pianist, respectively. Brian Eno also proved useful in sorting out the cocaine-addled compositions that surfaced on the trilogy of albums Bowie recorded in Berlin in the late 1970s. By far his most intriguing collaborations, however, seem to have been with the works of dead authors (according to one recent work, there were nearly 100 of them), a technique he had already tried out immediately before Diamond Dogs when he doused tracks from Aladdin Sane in glissando strings and the gay old literary world of Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies.

On the face of it, Orwell and Bowie made for strange creative bedfellows. Orwell was born Eric Blair in 1903, an inveterate Englishman and Etonian but also a writer with a singularly steely, cant-destroying approach to his journalism. Bowie, meanwhile, was the louche rock star. Orwell took a bullet in his throat in the Spanish civil war and Bowie shot heroin into his arm. Orwell was a schoolteacher and Bowie was an autodidact. Orwell didn’t even seem to have much interest in music; indeed, when writing in praise of the institution of the English pub, he famously stipulated they should have “no music.” It’s highly doubtful that he would have much cared for the world in which his latter-day admirer took up residence after scoring his first major commercial hit in 1969 with the title track of his second album, Space Oddity.

And yet. Bowie was born David Jones in Brixton in 1947, a matter of months before the first of the Windrush generation of African-Caribbean immigrants began arriving in the area bringing musical styles that would later feature in some of his most popular work. From the migrant branch of his own family tree—his paternal grandparents were Irish—one imagines he picked up his particular love of storytelling, and possibly, as well, the knack for musically repackaging the storytellers themselves.

One can see Orwell’s particular appeal for Bowie. They were both serial self-multipliers for one thing, each having changed his name early on in the interests of pursuing a certain sort of career path. In Bowie’s case, he was using music and technology to lift himself out of a fairly modest upbringing in a neighbourhood in which, as he later put it, “you always felt you were in Nineteen Eighty-Four.” The solidly upper-middle-class Orwell, on the other hand, used his work to lower himself, burnishing his bona fides as one of the toiling masses down and out in Paris and London. A modest soul who wanted little more from life than to keep the aspidistra flying in the window. Or so the Orwell story goes.

As the Bowie story goes, he originally intended to create a full-blown theatrical production of Nineteen Eighty-Four before Orwell’s widow, Sonia Brownell, turned him down flat when he inquired after the rights. According to this version of musical events, Bowie ended up settling for something vaguely similar to the original plan, retaining one or two tracks that happened to include the odd allusion to the book. I don’t believe a word of it. Diamond Dogs sounds like the project Bowie always intended it to be, and if I say that with feeling it’s because it was the album that first led me to Orwell as a teenager—the first time I read the book as a kid it pushed me straight back to the album, and the fact is, even now, I really can’t fully tell them apart.

Example: Have you ever noticed how virtually all 11 tracks on Diamond Dogs positively reek? The artist sings about smelling defecating dogs in the alley. He sings about something smells of “the blood of les tricoteuses” and the perfumed scent of a woman’s brooch that smells of “something mother used to bake.” He sings about a set (sex?) that “smells like a street,” and somewhere else he sings about the joys of powdering one’s nose. Honestly, has there been another artist so obsessed with scent? Well, yes, actually, there has been. John Sutherland even wrote a nifty book about him, Orwell’s Nose, which makes a case for him being in a league of his own, especially in the naso-sensitive Nineteen Eighty-Four, with all its bad air, bouquets of acrid cigarette smoke, petrol fumes, boiled cabbage and “a wave of synthetic violets” that flood Winston Smith’s nostrils when he first takes Julia into his arms. It makes the teeth tingle.

Bowie’s album beautifully captures the essential romance in the story. It starts when Winston steals his first glance at Julia but takes her to be just another rank-and-file member of the Anti-Sex League, Orwell’s version of a Twitter dog-pile in which members start each morning in a state of perpetual outrage against those who don’t toe whatever is perceived to be the latest Party line. Julia’s first words are given to him some time later on a scrap of paper passed on to him in the hall: “I love you.” She loves him. “When you make love,” she explains, “you’re using up energy; and afterwards you feel happy and don’t give a damn for anything. They can’t bear you to feel like that. They want you to be bursting with energy all the time. All this marching up and down and cheering and waving flags is simply sex gone sour.” This is all Winston ever wanted. And when he and Julia finally get around to sleeping together, the revolutionary potential of the act is indeed affirmed as a life-force capable of tearing a dictatorship apart. Well, just for one day.

Only one hell of a composition could possibly capture all that, but it is accomplished by the album’s best-known radio hit, ‘Rebel Rebel,’ with its three descending notes looped around the trashy guitar. Bowie salutes the kid whose mother is “not sure if you’re a boy or a girl” (which is sort of a dumb line when you think about it because, of all people, a mother would presumably know the sex of her offspring). Perhaps the sexual switch-hitter was also saluting himself. In any event, it’s a joyful noise about the wonders of lust, and listeners over the years have always tended to respond in kind. I watched a few thousand of them on a night of wind and lashing rain in February 2004 at one of the last concerts Bowie ever gave. He brought the Reality album show Down Under, and sure enough, ‘Rebel Rebel’ was the number that brought the audience to their feet to dance along in New Zealand’s capital.

As his doomsday project unfolded, Bowie kept the pleasure dome open a bit longer with the next song, ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll with Me,’ an unexpectedly upbeat power ballad built around Geoff MacCormack’s piano and Bowie’s own reverberated guitar. Holy mother of God, it’s a spectacular performance, one of Bowie’s most lyrically naked, and he quavers through the refrain with an unalloyed passion worthy of the book’s central characters: “I’ve found the door that lets me out!”

Or has he? The ballad ends, all is silence save the tics and specs of the needle in the vinyl, and then it’s on to the keyboard-driven ‘We Are the Dead,’ which of course is the last line spoken by Julia to Winston in Nineteen Eighty-Four. It’s a much more cinematic song, lyrically as well as musically, which makes sense. Our protagonists are involved in an affair of sorts, and love affairs tend to make their participants feel like actors in a movie, risking exposure in pursuit of illicit intimacy and desire—something the song, like the book, fleshes out with the sound of boots clumping up the stairs as the stormtroopers of the Thought Police prepare to storm the bedroom and wreak justice for the betrayal.

Lest the point of what he’s getting at is being missed, the next track is bluntly entitled ‘1984.’ Orwell would have been 80 when that year began, and in the song named for his signature year, Bowie appears to imagine how Orwell might have interacted with the culture had he lived another 34 years:

They’ll split your pretty cranium and fill it full of air,

And tell you that you’re 80, but brother you won’t care…

Not for Bowie the idea of the old man curdling into some kind of bitter contrarian in his autumn years. More like a reversal of roles; after spending most of the album sounding like an Orwell put to great music, he takes a moment out to make Orwell sound like a Bowie in the garret. Oh, and he shoplifts an absurdly catchy disco hook, replete with wah-wah guitar, filching it directly from the musical warehouse of Isaac Hayes, which he would plunder again for his next album, Young Americans.

Like the book, Diamond Dogs signs off with a meditation on language, which in Orwell’s case brings together the ideas he famously wrote about shortly before embarking on the novel in his essay “Politics and the English Language.” Bowie, now singing in a canyon-deep voice, takes some of the same ideas and puts them to a hesitant saxophone and muzaky synthesizer. The song, “Big Brother,” is named after Nineteen Eighty-Four’s central cult figure, a political tyrant from Oceania who may or may not have actually existed in the story but who arguably is still around and doing a brisk line of global business in 2021.

The track closes with “Chant of the Ever-Circling Skeletal Family,” a kind of Two Minute Hate session (this portion of the cut clocks in at 1’58”) in which Bowie and his vocalists are barely able to muster a coherent word in English. The chant culminates, like the chants in Nineteen Eighty-Four, with a needle-stuck-in-the-groove repetition of the word “brother.” It’s a terrific final flourish for the album, flouting as it does popular music’s golden rule of leading new collections of material with your strongest shot, and indelibly driving home the work’s Orwellian point: this ain’t rock and roll, baby, this is literature. Come over to the window and listen up one last time on the anniversary of Bowie’s death. It’s a bright cold day in January and the clocks are still striking 13.