Crime

Requiem for a Female Serial Killer—A Review

Wuornos had maintained that all seven victims had become violent and either raped or threatened to rape her, and that she had killed them in self-defense.

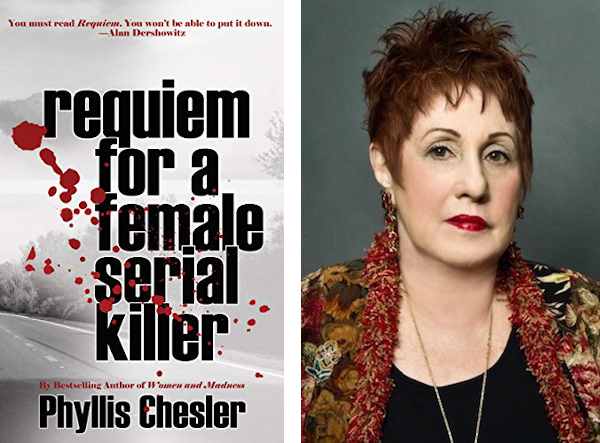

A review of Requiem for a Female Serial Killer by Phyllis Chesler. New English Review Press, 250 pages. (November 2020)

I.

Aileen Carol Wuornos was born in Michigan in 1956 and executed by lethal injection in Florida in 2002. She has been called America’s “first female serial killer,” but that wasn’t true by a long shot. Still, she might have been the first woman to kill (or be suspected of killing) a series of complete strangers—the victims of her homicidal female predecessors had been husbands, suitors, boarders, or children, old folks, or patients entrusted to them as nurse or caretaker. Wuornos’s seven victims (and there might have been more) were men between the ages of forty and 65 who had picked her up as a hitchhiker on Florida’s highways—mostly along Interstate 75, which slices north-south through the middle of the state, then veers west to the Gulf Coast, where it abruptly swings eastward through the Everglades to greater Miami.

The first of these killings, all of which involved multiple gunshots to the torso, took place in November 1989, and the last occurred in November 1990. She was arrested on 9 January 1991, identified by her fingerprints (she already had a decades-long criminal record) and eyewitness reports that placed her in or near some of the victims’ posthumously stolen cars with her lesbian partner, Tyria Moore. Wuornos had been a prostitute off and on since her teens, and it is entirely plausible (although far from certain) that most of the men who picked her up had sex in mind. Wuornos had maintained that all seven victims had become violent and either raped or threatened to rape her, and that she had killed them in self-defence. Nonetheless, she became the tenth woman in America to be executed after the US Supreme Court allowed the death penalty to resume in 1976.

Thanks to the media and to her unique status among female killers, Wuornos became a celebrity de scandale even before she and Moore were definitively identified. Lawyers, writers, filmmakers, criminal-justice reformers, save-a-soul evangelical Christians, and high-profile feminist activists all flew into the aura of the handcuffed, orange-garbed, man-killing, Death Row-dwelling Wuornos like gnats drawn to a porch light. Monster—the heavily fictionalised 2003 movie about Wuornos, for which actress Charlize Theron won an Academy Award—was only one of several dramatisations, biographies, film documentaries, television episodes, songs, poems, and even an opera that have capitalised on the macabre fascination the doomed and doom-dealing Wuornos elicited. Monster was made with Wuornos’s cooperation, and it was in production even as her state-appointed lawyers were making last-ditch efforts to stay her execution on grounds of severe mental incapacity. The Last Resort Bar, the biker hangout in Port Orange, Florida, where Wuornos was arrested, is now a tourist attraction, with a mugshot of Wuornos sitting on the bar itself and a mural of her likeness painted on the wall.

One of those mesmerised was Phyllis Chesler, among the most famous of the “second-wave” feminists of the 1960s and ’70s and author of a new book about Wuornos entitled Requiem for a Female Serial Killer. Chesler recently retired as professor of psychology and women’s studies at the City University of New York. She is now under a social-justice cloud because she protests honour killings and other female abuses in the Islamic world. She also remains a forthright supporter of Israel, a pariah country these days on much of the progressive and activist Left. Thirty years ago, however, she was riding on the fame of her 1972 book, Women and Madness, in which she argued that many women diagnosed as psychotic or otherwise deviant—by an overwhelmingly male psychiatric profession—were simply asserting their independence against social expectations of their sex determined by men. If they engaged in destructive or self-destructive behaviour, it was “a socially powerless individual’s attempt to unite body and feeling.”

So when, in late 1990, Chesler found herself watching a newscast describing the two mysterious armed women believed to be stalking the Florida roads for male prey, she concluded that Wuornos, still unknown to the public by name, was “a feminist folk hero of sorts.” She was Thelma and Louise avant la lettre—a woman finally giving as good as she got from men. A few months later, Chesler threw herself and as many allies as she could muster into Wuornos’s legal defence. (Requiem sometimes reads like a Who’s Who of second-wave feminism, with brief appearances by Chesler’s friends Gloria Steinem, Andrea Dworkin, and Zsuzsanna “Z” Budapest, the Los Angeles fortune-teller who invented Dianic Wicca.)

Chesler left her apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and flew to Florida, where she ran up collect-call charges from the jail, scuffled verbally with Tricia (“Trish”) Jenkins, the veteran public defender in charge of Wuornos’s criminal defence team, and tried to scrape together the money to pay the travel expenses of experts and former prostitutes willing to testify on Wuornos’s behalf. She wanted the court to understand “how dangerous the ‘working life’ really is; how prostitutes are routinely infected with diseases, gang-raped, tortured, and murdered; and that Wuornos had been raped and beaten so many times that, by now, if she was at all human, she’d have to be permanently drunk and out of her mind.”

The defence Chesler proposed for Wuornos was a variant of the “battered women’s syndrome” theory that allows women routinely beaten by their husbands or intimate partners to claim self-defence if they kill their abusers. This defence is available even if the victim hadn’t immediately threatened violence or reasonably seemed to do so—the only circumstance that usually justifies the use of lethal force against another human being. Since the 1970s, courts have occasionally invoked battered women’s syndrome (also known as the “Burning Bed” defence, after the 1984 made-for-television movie starring Farrah Fawcett), either to expand the concept of self-defence to include killings that would otherwise be deemed premeditated, or to bolster a claim of temporary insanity: a wife driven mad by her husband’s savagery to the point that she thinks she has no recourse but to kill him. Chesler hoped to extend this concept still further to include prostitutes, on the theory that, like battered wives, they experience near-daily violence from their male customers. Wuornos told Chesler and others that she had been raped repeatedly since adolescence by men whom she had thought were friends or clients or boyfriends. “I think it’s time to expand a woman’s right to self-defense,” Chesler told Gloria Steinem, “to include prostituted women. It’s time to argue that any woman, prostituted or not, has the right to kill in self-defense.” Most prostitutes, she writes, “are on the front lines of violent misogyny every single day.”

The voluminous legal documents and interview notes that Chesler collected from Wuornos and those connected to her never did turn into anything substantial, although over the years she wrote a law review article expounding her legal theories and contributed a foreword to a 2012 collection of the Death Row correspondence between Wuornos and her childhood friend from Michigan, Dawn Botkins. Then, in 2019, a box of papers fell from a shelf as Chesler was renovating her apartment, and she decided at last to write the “damn book,” as she describes Requiem: a reconstruction of Wuornos’s homicides from Wuornos’s point of view and a memoir of Chesler’s own involvement in the case.

II.

In January 1992, Wuornos was tried for the first of the killings. Richard Charles Mallory, 51, had been an electronics-store owner in Clearwater, Florida, with whom she had hitched a ride northward to take her to the motel near Daytona Beach where she lived with Moore. At that trial, and in previous interviews with the police, she testified that Mallory had driven her to an isolated area near Orlando, and instead of engaging in the consensual sex-for-cash for which she had bargained, he had tied her up, beaten her, raped her brutally both vaginally and anally, and announced that he intended to kill her. At this point, according to Wuornos, she reached for a .22 pistol that she carried in her purse and shot him at least three times. She covered his body with a piece of carpeting and drove his 1977 Cadillac to her motel. A few days later, she abandoned the car in a nearby wooded area, along with Mallory’s now-empty wallet and credit cards. She said she had killed him in self-defence.

The jury clearly did not believe her testimony, partly because an initial jailhouse confession (admitted into evidence over Trish Jenkins’s objections and made over the objections of a deputy public defender present during her questioning who had advised her not to talk) did not mention rape; partly because Mallory’s body had been completely clothed with his pants zipped and the pockets hanging out when it was discovered; partly because she had told conflicting stories about the other six murders (admitted into evidence to prove intent and a pattern of conduct); partly because items from Mallory’s car (some of which bore Wuornos’s fingerprints) turned out to have been pawned or left in a rental storage unit near Daytona Beach; partly because Wuornos’s account of the shootings didn’t match the forensic evidence; and partly because Wuornos’s volcanic temperament had made a shambolic mess of the trial. Taking the stand against her defence team’s advice, she alternately raged against her accusers and retreated behind the Fifth Amendment during cross-examination. The jury spent less than two hours deliberating before returning a unanimous verdict finding her guilty on a range of charges, including first-degree murder and aggravated armed robbery.

Over the next five months she pled guilty or no contest to five more murders of men who had picked her up in their cars (she had already confessed the crimes to the police), for which she received five more death sentences. The seventh victim was 65-year-old Peter Abraham Siems, a retired merchant seaman and evangelical Christian missionary from Jupiter, Florida. Witnesses had spotted two women crashing and then abandoning Siems’s 1988 Pontiac Sunbird near Orange Springs on 4 July 1990; Siems had been missing since June, and the interior of the Sunbird was stained with blood. But his body was never found, and Wuornos was never charged with his murder. As she had with Mallory’s death, Wuornos told many conflicting stories about the circumstances of those six additional homicides during the more than ten years she spent on Death Row, trampolining between boasts that she had killed in cold blood for the money and a vehement insistence that the shootings had been her only defence against repeated rape attempts.

During the penalty phase of the Mallory trial, the jury found enough “aggravating circumstances,” including that the murder had been “cold, calculated, and premeditated,” to warrant capital punishment—even though Jenkins had presented evidence from three psychiatrists who had examined Wuornos and concluded that she suffered from borderline personality disorder so severe it left her unable to conform her conduct to the law. Jenkins had personally traveled to Wuornos’s childhood home town of Troy, Michigan, where school friends and neighbours provided evidence that Wuornos had endured a strikingly ghastly childhood and adolescence. This was all recorded in a 1994 Florida Supreme Court decision upholding her conviction and capital sentence in the Mallory case.

Wuornos’s mother, Diane Wuornos, had been only fourteen when she married sixteen-year-old Leo Pittman in 1954, giving birth to a son, Keith, in 1955. Aileen was born the following year. She never met her father because at the time of her birth he was already separated from her mother and incarcerated for a series of sex offenses involving the rape and kidnapping of minors. Diagnosed a schizophrenic, he served time in various prisons and mental facilities, and hanged himself in 1969. When Aileen was four, Diane Wuornos abandoned her children, deeming them too much trouble to raise and leaving them with her own parents, who legally adopted them. Both grandparents seemed to be alcoholics (the grandfather eventually committed suicide, and the grandmother died of a liver disorder).

There was evidence that the grandfather verbally and physically abused Aileen. Her biological uncle/adoptive brother, Barry Wuornos, who had been called as a prosecution witness at the Mallory murder trial, disputed this. But it was undisputed, at least according to the Florida Supreme Court, that trouble had swirled around Barry’s niece/adoptive sister as she reached adolescence and became a disciplinary problem at home and in school. She was diagnosed as mildly cognitively impaired with other impairments of hearing and sight. At the age of fourteen, she got pregnant after being raped by a family friend. Her grandfather forced her to give up the baby boy, born in 1971, for adoption. She dropped out of school, ran away from home, and was turned away by her grandfather on her return. So, she began living on the streets (or, as she told interviewers, in abandoned cars in the Michigan woods), taking up a “a life of prostitution and alcohol and drugs,” according to the Florida Supreme Court.

She amassed a record of arrests and convictions: drunk driving, petty theft, auto theft, forged checks, armed robbery (for minor sums), barroom assaults, resisting arrest, shooting a gun from a car. Early on she had armed herself with a .22 pistol, along with other firearms and plenty of ammunition. In 1976, at the age of twenty, she hitchhiked to DeLand, Florida, and contracted a hasty marriage with 69-year-old retired yacht-club president Lewis Gratz Fell. A few weeks later, Fell took out a restraining order against Wuornos after she got into barfights, was arrested for assault, and beat him with his own cane (the marriage was promptly annulled, and Fell died in 2000). Keith Wuornos died of cancer in Michigan not long after the Fell adventure; Aileen spent her way through his US$10,000 life-insurance payout in just two months, including buying herself a new car, which she promptly wrecked.

There were more arrests, more drinking (her beverage of choice was can after can of Budweiser), more gun incidents, and more verbally and physically hostile altercations with neighbours, fellow bar customers, and bus drivers, since she typically took public transportation to the highways where she plied her trade. In around 1986 she met then-24-year-old Tyria Moore, an off-and-on hotel maid, at a lesbian bar in Daytona Beach. They moved in together, and Wuornos supported Moore with her earnings as a prostitute. Those earnings were scant, however, as Wuornos worked only sporadically (she drank the rest of the time). The two were regularly evicted or all-but-evicted from their cheap motel rooms and other seedy quarters, with Wuornos trying to make rent by wheedling acquaintances and selling or pawning items she said her johns had given her. Moore proved to be the key to Wuornos’s convictions; initially pinpointed as a possible accomplice to the murders, she cooperated with law enforcement and helped induce her confessions.

III.

Chesler’s account of all of this in Requiem is often riveting but just as often disappointing. She has a punchy, intimate, highly readable prose style, sliding credibly into Wuornos’s own slang contractions (“hadda,” “outta,” “kinda”) as she devotes the first hundred pages of the book to a reconstruction of the killings and their preludes and aftermaths. It’s not the most chronologically coherent reconstruction, however—Chesler gets dates and other details wrong here and there, and jumps around impressionistically in time and place (my advice to readers who want to make sense of the book is to supplement Chesler’s account with the vast trove of Wuornos material on the Internet). The book also could have used a map, given the wide geographic range of the central Florida landscape where the bodies and abandoned vehicles of the victims turned up.

But the most problematic aspect of Chesler’s account is this: “Everything I write is based on facts: Legal documents, transcripts of in-person and phone interviews, diary entries, correspondence, etc. However, what you are about to read is also a genre-blended form of fiction/non-fiction.” And “fiction/non-fiction”—that is to say, mostly fiction—it is. In Chesler’s account of the homicides, all seven of the men Wuornos filled with bullets had either raped her, were trying to do so, or were otherwise treating her with violence and contempt. In fact, we know almost nothing about the actual circumstances in which these men died other than what Wuornos revealed in her own erratic and contradictory accounts. (Indeed, as Suzanna Diamond, a literature professor at Youngstown State University, pointed out in a 2019 article in Anthurium, Wuornos tantalised her advocates, including Chesler, with the prospect of coming clean at last with the full stories of the homicides but never did so.)

Two of the victims’ bodies were found naked, another’s nearly so, which suggests sexual encounters—but we can only speculate about how the men ended up undressed. The only really plausible rapist was Mallory. In 1957, when he was nineteen, he had been arrested for trying to pry the blouse off a woman he encountered in her home while working as a delivery man. Pleading insanity, he ended up serving about five years in a Maryland rehabilitation facility for sex offenders, including time for a failed escape. The twice-divorced Mallory’s main hobbies at the time he picked up Wuornos in November 1989 were lap dancers and pornography. But even with Mallory, it is hard to see how a 32-year-old crime committed as a teenager necessarily translated into a sadistic encounter decades later.

Furthermore, Chesler’s account of the legal record sometimes doesn’t jibe with the Florida Supreme Court’s version of events. For example, Chesler asserts that when Wuornos asked for a lawyer to be present during her jailhouse confessions as she talked on the phone with Moore, “the cops take their own sweet time about providing one. And Wuornos just keeps on talking.” But the Florida Supreme Court said that no such dilatoriness had taken place: Wuornos “freely waived her rights and confessed, contrary to advice of counsel both before and during the first confession and later” [italics mine]. Chesler also writes that Mallory’s most recent ex-girlfriend, Jackie Davis, had been ready to testify at trial “about how violent Mallory had been towards women,” but that the trial judge, Uriel Blount, “did not allow her to testify.” In fact, according to the Florida Supreme Court, Wuornos’s defence team had proffered Davis’s testimony outside the jury’s hearing, in which she stated that “[a]part from hearsay, to her personal knowledge Mallory always had been gentle toward women.” The defence lawyers decided not to call Davis as a witness, for obvious reasons. Such discrepancies don’t give a reader much faith in Chesler’s reliability as a narrator.

Chesler’s account of her efforts to insert a version of what might be called prostituted-woman syndrome into Wuornos’s legal defence are similarly scattershot, but also entertaining, especially her Park Slope take on central Florida: a flyspecked, billboard-studded flatland most of the population of which seems to consist of gun nuts, racists, bikers, juicers, topless waitresses, wife-beaters, Jesus freaks, cross-burners, and abortion-clinic arsonists (a clinic in Ocala went up in flames in April 1989). Casting a long gray shadow over the landscape—and also Chesler’s feminist sensibilities—is the ghost of one of the 20th century’s most famous serial killers, Ted Bundy. Bundy was executed in Florida in January 1989 after a highly publicised trial for three of the thirty gruesome rape-murders to which he eventually confessed. Chesler points out that the lead prosecutor at Wuornos’s trial, then-State Attorney John Tanner, had, before his election to office in 1988, spent hours praying with Bundy on Death Row as part of a self-created prison ministry. In Chesler’s view, this encapsulated the justice system’s disparate treatment of men and women accused of murder: “My people (women) are sometimes crazy—but Bundy was handsome, charming, and well spoken.”

Chesler perforce—in order to gain access to Wuornos in jail—makes the acquaintance of Arlene Pralle, a forty-something born-again-Christian horse breeder who latched on to Wuornos soon after her arrest. Pralle legally adopted Wuornos as her daughter so as to bring her the Lord’s love, phoning her in jail almost every night, exchanging swoony letters with her, and acting as media gatekeeper (in exchange for cash, according to her detractors). Apparently under the impression that “Dr. Chesler” the professor is a medical doctor, Pralle asks if she can get her a prescription for Valium. But she does put Chesler in phone contact with Wuornos, who devotes most of their conversations, all at Chesler’s expense, to importuning her (unsuccessfully) into hiring private lawyers to replace Jenkins’s public-defender team, and wheedling for money to cover her jail commissary expenses. (Chesler does not meet Wuornos personally, however, until she is already on Death Row.)

Chesler never did manage to persuade Jenkins to buy into her battered-prostitute defence theory. She and her academic ally, Meg Baldwin—then a law professor at Florida State University and currently the executive director of a rape crisis centre near Tallahassee—never seemed to make the technical specifics of their argument clear (Baldwin was supposed to be doing the legal research). Nor does Chesler ever divulge who the proffered pro bono experts regarding beaten-up prostitutes—around eleven of them—were supposed to be, apart from Chesler herself and Judy Wilson, then-as-now director of a battered-women’s shelter in Ocala. Jenkins tells Chesler that Wilson would be “death in the courtroom” if she testified for Wuornos, and from Chesler’s account, it’s easy to see why.

Wilson and her husband, lawyer Jim Shook, appear in Chesler’s book as colourful, trash-talking local iconoclasts with yarn after gossipy yarn about the “real uppity” women and the “steel magnolias” of the South who never get a fair deal from Southern judges or Southern juries when they kill their lovers or hide their children from ex-husbands (Shook claims to have been the victim of an attempted poisoning right in the courtroom during a custody battle). But neither of them seems especially focused on the legal issues at hand—and nor, it would seem, is Chesler. Soon enough, and without much explanation, she is back in New York having Wuornos’s horoscope cast by celebrity astrologer Charles House and, later, watching the trial on Court TV from her Brooklyn apartment.

Chesler doesn’t think much of Trish Jenkins’s strategic talents as a lawyer (“she’s a busy lady,” we learn, with “many bristling feathers” who wants to be “one of the boys”). In fact, Jenkins seemed to have done her best with the impossible task of defending a client bent on self-sabotage at every turn. She had urged Wuornos to plead insanity in the Mallory case, which might have saved her life, but Wuornos would have none of that. (Nor would Chesler, who wanted Jenkins to argue that Wuornos was simply “traumatized” by her professional experiences.)

IV.

The final chapter of Requiem, entitled “Love Letters,” consists of correspondence between Chesler and the incarcerated Wuornos starting in November 1991 and continuing through April 1993, when Wuornos abruptly cut Chesler off. “I thought perhaps you were, OK,” Wuornos wrote. “But, I can diffenately [sic] sense swindle in you. I have others helping me on lawyers, etc. So this will be the final reply back. Hope you find Jesus Christ in your life soon.” This was typical of Wuornos. As Suzanna Diamond points out in Anthurium, Wuornos waxed first hot and then cold, with accusations of double-dealing, on everyone with whom she associated: Tyria Moore; Trish Jenkins; Arlene Pralle; Steven Glazer, the guitar-strumming hippie lawyer whom Pralle found to replace Jenkins after the Mallory conviction; filmmaker Nick Broomfield who made two documentaries about Wuornos with her cooperation and even, at the end, Dawn Botkins, her lifelong loyal friend. As had been the case with the collect phone calls, Wuornos’s letters to Chesler while they lasted consisted mostly of angling for help, financial and otherwise: finding new lawyers, getting the National Organization for Women involved, working out a book deal whose proceeds would go partly to Pralle and thus indirectly to Wuornos, postage stamps and other personal items.

Chesler had wanted to turn Wuornos’s case into a political cause. “I chose to see what Wuornos did,” she writes, “as a protest against the men who both buy women and, in addition, also act as if our streets and workplaces are their private brothels. Enough. No more.” Wuornos, she elaborates, was “a prostitute who fought back.” But Chesler’s afterword to Requiem contains a startling piece of self-revelation—it finally dawns on her after all these years that Wuornos had been doing exactly what she had first confessed to doing: murdering men for their money. “I was so focused on exposing how violent prostitution is for the prostitute, so obsessed with arguing for a just trial for Wuornos (which I do not regret), that I could not, at the same time, allow myself to acknowledge that I might also be defending a serial killer. And I was.”

Yet it is hard to take the second-wave feminism out of the second-wave feminist, even a second-wave feminist as honest with herself as Phyllis Chesler eventually manages to be. Like other second-wavers she remains convinced that prostitution is entirely a crime committed by men against women who are no more than their hapless victims—victims who might be driven over the edge by one beating or violent penetration too many. “I see [prostitutes] as human sacrifices,” she declares. “I understand all the forces that track 98 percent of girls and women into the ‘working life’: Dangerously dysfunctional families; physical and sexual abuse; drug addicted, absent, or imprisoned parents; serious poverty; homelessness; being racially marginalized; tricked or kidnapped into prostitution by a trafficker; sold by one’s parents; having too little education and few marketable skills; and, having absolutely no other way to eat or to feed your children.” To the end, Wuornos remains an archetypal figure: the “prostitute who continues to face violence and death every day.”

There is no doubt that prostitution is a dangerous occupation—which is why there are pimps, or at the high-priced escort end, layers of protection in the form of screening, drivers, and bodyguards. By its nature, prostitution involves being alone with a strange man whose intentions are, at the very least, opaque and who at worst may feel entitled to rape and batter as part of the sexual services his dollars paid for. But one need not subscribe to the cliches about the Happy Hooker or the notion that prostitution is simply a career choice that pays better than administrative work to appreciate that it has a wilful, transactional dimension that Chesler ignores.

Selling your body does in fact pay better: Even a lowly streetwalker can earn as much in 20 minutes as a McDonald’s cashier standing behind a counter makes in an entire morning. Prostitution is thus a vice-magnet for the unfortunate and desperate, but also for the lazy, the short-horizoned, the drug-addicted, and those, like Aileen Wuornos, who spend the greater part of their day chugging Budweisers. To believe otherwise is to deny women moral agency. Chesler quotes Wuornos as saying: “If men would keep their money in their pockets and their penises in their pants, there would be no prostitution.” But it’s equally true that if women didn’t keep raising their skirts to see what money they could get from men’s pockets, there would be no prostitution, either.

Aileen Wuornos was a pitiable human being. One of the two photos of her in Chesler’s book (the other is a mugshot), poses her at age twenty with her husband of a few weeks. It shows how pretty she once was, although the signs of self-abuse are already evident on her face and in her neglected teeth. She was genetically cursed on both sides of the family, and she endured a childhood so starved of mother-love that she showered affection on whoever gave her the crumbs of attention she craved: boyfriends, girlfriends, Arlene Pralle. Notwithstanding her averments to the contrary, she was clearly mentally disturbed—probably schizophrenic like her father—and the violent outbursts that began in childhood make it likely that she became an outcast at an early age because other people were afraid to have her around.

Chesler points out that Wuornos resembled Valerie Solanas, Andy Warhol’s would-be assassin in 1968. The two women shared disturbingly similar biographies and symptoms: early parental divorce and abandonment, teen pregnancy (by the age of fifteen, Solanas had had two children, both of whom were given away), panhandling and prostitution, episodes of physical violence that began in pre-adolescence, steady mental deterioration throughout their lives. Warhol survived, but lived in pain for the rest of his life as a result of the damage his internal organs sustained from Solanas’s bullet. Solanas ended up serving three years in prisons and mental institutions, eventually dying destitute in a fleabag hotel in 1988. Wuornos left behind at least seven dead bodies, of men who at the most were trying to buy what she was purportedly selling, some of whom were quite possibly just giving a lady a lift, and all of whom were mourned by grieving relatives.

This raises the perennially troubling question to which there never seems to be a good answer: What is a society supposed to do with grievously abused and mentally deranged people who nonetheless inflict lethal violence upon others—and with a certain degree of calculation? To what extent, if any, should insanity legally excuse premeditated murder? Just before she was put to death, Wuornos was asked if she had any last words. “Yes,” she replied. “I would just like to say I’m sailing with the rock, and I’ll be back, like Independence Day, with Jesus. June 6th, like the movie. Big mother ship and all, I’ll be back, I’ll be back.” And with that strangely poetic statement, which undoubtedly made sense to her if to no one else, the life of this severely damaged—and damaging—woman was extinguished on 9 October 2002 at 9:47am EDT. Her life story, as Chesler eloquently observes, was “a horrifying and pitiful tale with an inevitably sordid ending.”