Activism

My Journey from Born Again Christian to the Church of Woke—And Halfway Back Again

How could we even conceive of something like social justice without the moral framework offered by religion?

My Christian faith died thrashing in 2004.

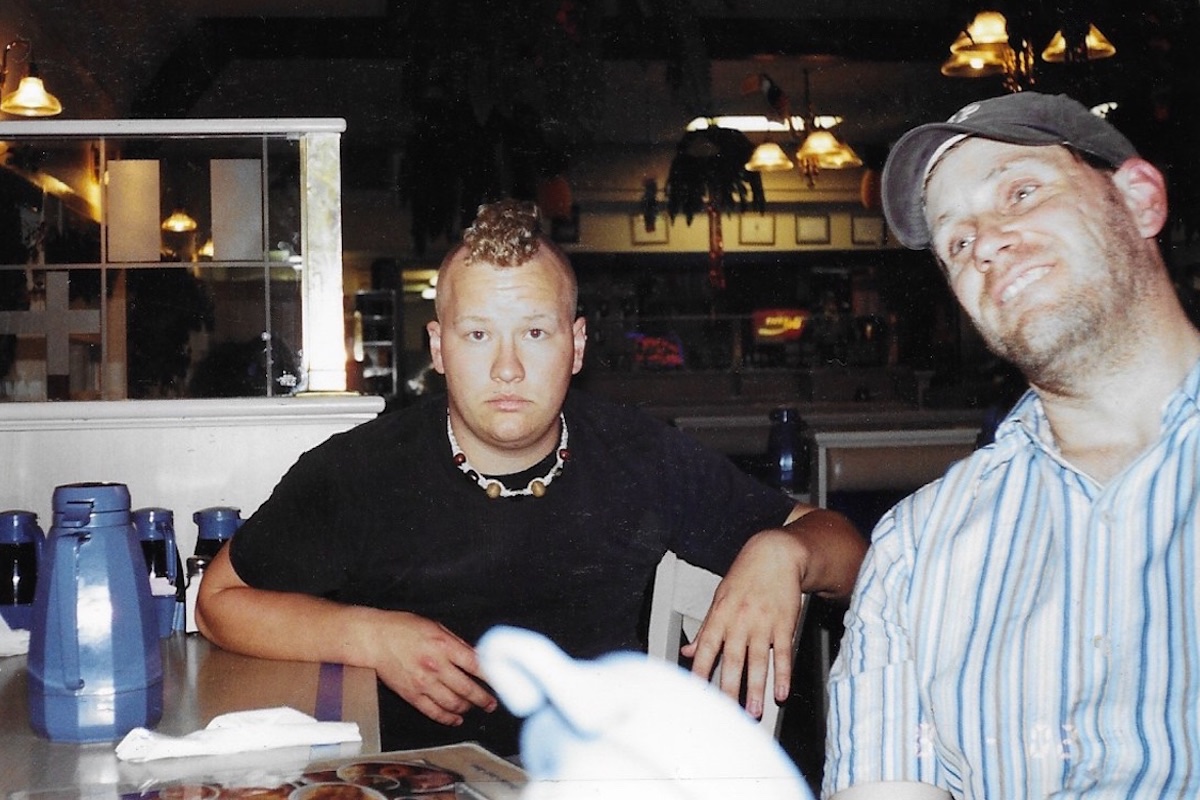

It was the thick of summer, and I was a hyper-earnest teenage bible-thumper volunteering my time for a church-mission trip in the slums of Tijuana, Mexico. I was partway through a Sunday-School lesson with a small group of boys when my youth pastor—a man I considered equivalent to a Jedi Master, religious mentor, and rock star all rolled into one—tapped me affectionately on the crown of my head. He awkwardly stepped through our cross-legged circle en route to an ominous black cruiser with tinted windows that was idling outside. Somehow, I understood immediately that this would be the last time I saw him in person.

Earlier that morning, I’d woken up inexplicably crying and dehydrated, in the midst of murmuring my way through a desperate prayer of some sort. I’d recently finished The End of the Affair, a Graham Greene novel in which the spiritually embattled protagonist concludes his story with this line: “O God, You’ve done enough, You’ve robbed me of enough, I’m too tired and old to learn to love, Leave me alone forever.” I remember the alarm I felt when I read those words, like they were heralding my rebirth as an atheist. I was being seduced by reason, by free thought, by the impulse to become a heretic. Did I actually have what it took to turn my back on the church, on God, on my youth pastor? Was I really destined to abandon my salvation, to ditch everything that gave my life meaning? My prayers were manic and pleading as I scribbled them down in my journal, begging for God to reveal himself in a meaningful way or lose me as a follower forever. It was the sort of spiritual blackmail that never works.

Shortly after the police car departed, the church elders gathered us missionaries together for some life-altering news: Our youth pastor had been arrested, though the nature of the charges was unclear, and was being taken to a nearby police station for processing. It wasn’t until we returned to Canada a week later that we learned that he stood accused of molesting two boys. As it turned out, he was destined to spend over a decade in a dank penitentiary called La Mesa, living through horrific conditions that included multiple riots and regular overcrowding.

My trust was shattered. Right when I felt I needed his guidance most, my pastor had been unceremoniously excised from my life—yanked off his pedestal and humiliated (not unlike the Jewish Messiah he worshipped, as I then thought). Meanwhile, I was busy unburdening myself of my allegiance to Christian dogma, while trying to sort out how to approach the world without a spiritual support system. If I no longer believed in grace, or the resurrection, or the exclusive divinity of Jesus of Nazareth, then what did I believe in?

All of this coincided with an internecine drama playing out within the Anglican church, of which I was a member. Our bishop, a fiery contrarian named Michael Ingham, had published a book called Mansions of the Spirit that was essentially a defence of pluralism—his first sin, in the eyes of followers—and had also, much more controversially, embraced the idea of same-sex marriage. The result was akin to civil war, splitting entire congregations down ideological lines. This in turn led to a series of expensive legal disputes and bankruptcies. Years previously, Ingham had overseen my confirmation at age 14, praying over me while I knelt at the altar of his Vancouver cathedral. As he went on to make headlines for his defiant stances and subversive rhetoric, I couldn’t help but wonder if I was channeling his influence.

I would have been loath to admit it at the time, but my flight from faith was part of a well-established cycle within our church community. Children are raised in the faith, become disillusioned in their late teens, rebel throughout their 20s, then return humbled and newly devoted once their own children enter the picture. While I was convinced I was embarking on a heroic, solitary journey, the truth was that everyone around me seemed to be divorcing themselves from Christianity in favour of secularism. Free to party, engage in premarital sex, and disavow the teachings of our childhood, we were hell-bent on burning down the cultural edifices of the past as we envisioned an exciting God-less future. As Nietzsche put it, “no price is too high for the privilege of owning yourself.” By the time I reached grad school, being Christian had become a faux pas to most of the people I now met. Only bigots, homophobes, and rednecks believed in Jesus.

Smugly clutching my copies of Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion, Sam Harris’s The End of Faith, and absolutely anything by Christopher Hitchens, I enlisted in the atheist club at the University of Victoria, and made a name for myself as an iconoclastic local columnist, best known for calling Pope Benedict XVI a jackass alongside a cartoon of His Holiness with a condom pulled over his head. How had I ever fallen for this shit, I wondered. I decided to identify as an apatheist (someone who isn’t even interested in discussing God’s existence), and settled into an aggressively non-religious existence, in which the only spiritual truth I felt capable of embracing was my own incapacity to grasp life’s great mystery. As 18th-century hymn-writer Gerhard Tersteegen once wrote: “A God comprehended is not God.”

I felt confident that Christianity was a thing of the past, and that human society should have no problem progressing now that it had successfully shed its superstitious roots. I put my faith in science and logic and the basic goodness of human beings. I felt I had earned the privilege to un-choose my religion.

As I approached adulthood, I found my political and social sensibilities naturally drifting to the left—the realm of the artists, the activists, the shit-disturbers. In this environment, Christianity was mostly understood to be an oppressive and destructive force, responsible for atrocities such as Indigenous residential schools and the Crusades. Most of my left-leaning comrades had little or no knowledge of the moral content of my childhood religion, had never really engaged with the Bible, and had no appreciation for the role this intellectual tradition had served in people’s lives. God was an outdated concept, and had no relevance in the real goal, which, we assured ourselves, was social justice.

In this narrative, Bible Belt conservative types were the villains, opposing women’s right to choose and keeping people hog-tied to gender roles. Over the years, I began to instinctively despise evangelists and preachers, to judge faith-having friends as too blind to understand the contradictions of their religion, and to consider myself enlightened in a way they could never be. When Bill Maher came out with his documentary Religulous, I was happy to laugh along with the audience at the shameful ignorance on display. I was smug as hell, and mean.

Regardless of how correct I may have felt, or justified in my self-righteous atheism (or apatheism), the truth was that losing my faith was the most traumatic and damaging experience of my life—and it fucked me up for years. I didn’t have a moral framework to work within. I no longer felt charged with holy purpose, and I never found a suitable replacement passion or philosophy to inform my daily life. It was like going through withdrawal and coming to terms with the idea that I would never be high again.

At times, I fantasized about monkeying around with my mind, turning off my capacity for critical thought, just so that I could truthfully re-engage with a church community. Whenever I found myself at a church wedding, I would lament the loss of wonder in my life. I missed the music, the pageantry, that brain tickle that comes with glimpsing the unknowable. I watched my friends and family continue to derive comfort and joy from a tradition that has existed for thousands of years, and wondered if maybe I was the stupid one. Like the many people who had cycled out of church before me, I was beginning to wonder if maybe I could salvage some bathwater—if not the whole baby.

My worldview became increasingly progressive as I transitioned into a career as a journalist. I applauded the Slut Walk and dated a queer woman. I began to educate myself about Indigenous issues, including those detailed in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, and began to infuse my work with the same moral passion I’d once reserved for sharing my faith. I covered affordable-housing protests, shook hands with Canada’s then-leading leftist, NDP leader Jack Layton, and mercilessly made fun of Sarah Palin. I pictured myself as a Joss Whedon type, an ally to women, always looking out for the little guy. I didn’t believe in the devil anymore, but I certainly believed in climate change, income inequality, and rape culture. I performed in burlesque, experimented with drugs, and championed trans rights. Finally, I was a believer again.

Then came #MeToo. When the hashtag first started trending on social media, I bought into all of it. I was complicit, stained with an original sin called toxic masculinity. I wrote articles about the movement, and tried to internalize its messages—going so far as to explore the topic with my therapist, and to think of ways to grapple with mistakes I felt I’d made in the past.

This was something I recognized from Christianity: It was confession time, and after that comes forgiveness. I took to social media to proclaim my failings, only to find the online mob considerably less forgiving than your average priest.

Over the course of following high-profile sex scandals, including one involving a false report against my former thesis advisor Steven Galloway, I began to realize that this movement wasn’t as altruistic or high-minded as I’d originally believed. There were fundamental rights being overlooked, like the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty—and nobody was talking about forgiveness. I started to admit to myself that I fundamentally disagreed with some of the central tenets of the woke ideology being pushed on us, and worried that I was becoming a heretic all over again.

Yet I still stubbornly held myself apart from right-wing thinkers out of some tribal impulse that helped me maintain my rejective posture toward Christianity. At some secret level, however, I was taking inventory of the deeply held beliefs I’d retained through it all. I still believed in turning the other cheek, that I was fearfully and wonderfully made, that we should honour our bodies. And as I saw people begin to dog-pile cops, vilify entire swaths of society as hateful, and celebrate cults that advocate mutilating children, I felt like the only sane member of a family going bonkers. They were fundamentally fucking with language, cancelling artists to coddle the feelings of dishonest virtue-signallers, and smearing anyone with divergent sensibilities with epithets like “Nazi,” “TERF,” “Karen.” This was a club I didn’t want to be a part of anymore. It had become its own demented religion.

So once again, I find myself where I was 16 years ago—questioning the beliefs I’ve held for years and wondering if I have to build my worldview from scratch again. As was the case in 2004, my intellectual drift isn’t an entirely solitary phenomenon. In many ways, I’ve become caught up in a cultural undercurrent that’s building wider momentum: As the followers of the Church of the Woke become increasingly radical, they’re triggering a mass exodus of politically homeless leftists who simply can’t buy into their dogma. And we’re all becoming increasingly evangelical about our beliefs, whether that means asserting that men can’t turn into women, that prostitution is inherently exploitative, or that the concept of systemic racism has gotten so expansive that it’s become essentially meaningless.

Recently, Richard Dawkins remarked that he was rethinking the utility of religion, if not the truth of it. And opponents of wokeism such as Ayaan Hirsi Ali, J.K. Rowling, and Joe Rogan are challenging the power of cancel culture. Feminists are finding common cause with Christian fundamentalists over the fight to protect women’s rights and oppose gender ideology. Some progressives are even starting to question why a woman’s religious beliefs should disqualify her from a deserved spot on the US Supreme Court. People are becoming aware that our cultural push for diversity and tolerance has backfired, creating a needlessly toxic environment for people of all faiths. Whether we’re arguing about God or gender or politics, there needs to be a recognition that some of the absolute truths that we’ve long sourced from religion shouldn’t be discarded simply because we no longer believe in a certain deity.

In his new book Dominion, atheist author Tom Holland takes readers through a history of western Christendom, demonstrating how our culture remains steeped in religious ideology. Everything from our vocabulary to the way we measure time has been affected by Christian heritage. How could we even conceive of something like social justice without the moral framework offered by religion? How can we judge the moral horrors of murder and war and pedophilia if we don’t believe in a fundamental difference between good and evil? In one example, Holland shows how our contemporary views of consent and rape stem from religious teachings about the sacred nature of the body and the sanctity of matrimony.

Some of these teachings have morphed or evolved over the years, but the truth is that no matter how aggressively the woke try to dismantle our cultural history, our entire concept of reality is constructed with Christian language and infused with Christian ideology. We tried to break up with religion, but never successfully moved out.

* * *

Though my youth pastor was convicted of crimes in Mexico, he maintained his innocence. Whatever the extent of his wrongdoing, I know that it’s unfair to use him as a scapegoat as a reason for why I lost my faith. But my feelings about Christianity are inextricably intertwined with my relationship with him. If I couldn’t trust him, then how could I trust what he taught me about God?

For years I wasted time feeling guilty, knowing that I was disappointing him, still eager for the approval of a convicted pedophile. Though many in his situation would lose their faith, he doubled down on his commitment to Christ, and even started a prison church before getting out of jail and coming back to Canada. He may have been a sinner, and he hurt vulnerable people. But when it came to his internal struggles with faith, he wasn’t a lifelong hypocrite. I keep telling myself that even if he was a criminal, like the countless Catholic priests who’ve been exposed for their abuses, it wasn’t fair to judge the truth of the church’s teachings based on the moral failings of its proponents. He was just a colourful excuse.

This year, I married a Christian woman, one who accepts that I will probably never again believe, and became the father of a little girl. I remain deeply ambivalent and often hostile toward the religion of my youth—but still stood proudly by as my daughter was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church at the bequest of her grandmother. She’ll grow up learning stories about the Bible, hearing teachings about a benevolent creator who loves her, and will pray every night before bed. She’ll also be free to ask questions, and to choose a different path. The fact that I strongly reject certain tenets of Christianity doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate a rousing rendition of Jesus Loves Me or recognize the intrinsic truths apparent in the mythology. In the same way, I plan to retain my general allegiance to the political Left, even if I secretly espouse beliefs that mark me as worthy of excommunication. And I will continue to oppose the noisy idiots intent on crucifying people.

After crucifixion comes resurrection. It’s something they teach you in Sunday school.