Social Media

Relearning How to Read in the Age of Social Media

People who don’t actively seek out books or articles inevitably lead more restricted lives because extended prose remains the most effective means of communicating complex ideas.

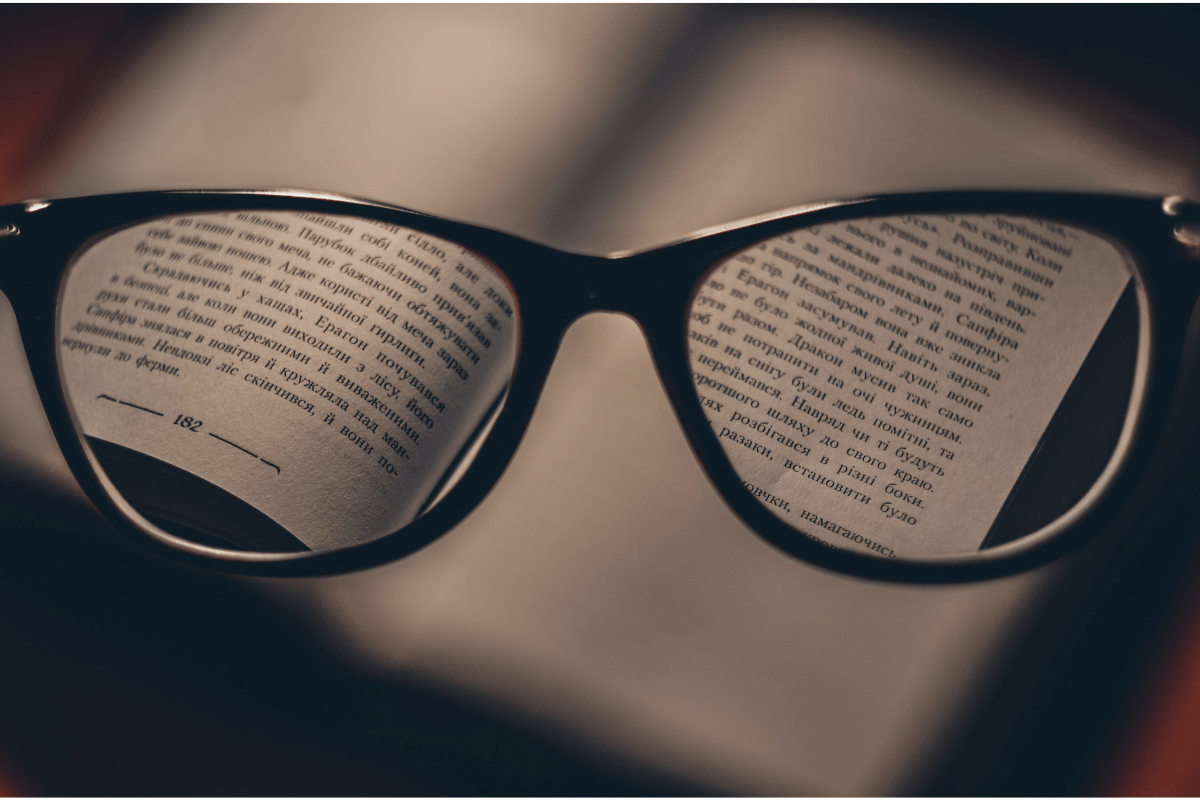

However amusing the meme or moving the pictures, reading—not gazing—remains the cornerstone of our civilisation. People who don’t actively seek out books or articles inevitably lead more restricted lives because extended prose remains the most effective means of communicating complex ideas. If your reading never strays beyond the demands of a colleague’s email or the brevity of a friend’s social media message, you live like a foreigner in your mother tongue, moving through the world partly sighted, a second-class citizen lacking a passport to ideas.

That is why millions of pounds of international aid are spent on global initiatives to improve literacy. But the ubiquity of the computer chip has meant the whole business of reading, the physical experience of engaging with extended prose, has brought about dramatic changes that we are struggling to acknowledge, never mind understand. Meanwhile, our educational system behaves as though Fleet Street still existed and professional authors still used Tippex. The ubiquity of costly computers and infrastructure has not in itself done anything to change academic attitudes to reading or to texts even though the way they are produced has been completely transformed.

Readers spend many hours reading from screens, yet sales of books remain at record levels. According to the Publishers Association, in 2019 print sales in the UK rose by three percent to £3.5bn while digital sales rose by four percent to £2.8bn (this includes a 39 percent increase in audiobook downloads). Technology has changed the way we engage with prose and hence with others’ thoughts, immeasurably, and it’s time we started to think more deeply and productively about that change.

As a schoolboy reader, my focus was the texts themselves. D.H. Lawrence and T.S. Eliot were just labels, George Orwell at least had the same Christian name as my own father, but was hardly less concrete a personality for that and even Shakespeare figured in my imagination as nothing more than a bald-headed, inanimate bust with a lace collar. Later, as a student of English literature, I maintained the habit of divorcing my primary reading from secondary studies of history, psychology, and biography. Although I knew a great deal about George Eliot’s and D.H. Lawrence’s lives, and even about the geography and culture of the industrial Midlands we had all grown up in, I was able to put all that aside the moment I turned a page of Middlemarch or Sons and Lovers. I had learned to read the words in front of me. Although the warning signs were there, no one insisted I bring anything extraneous to the experience, certainly nothing as grubby as politics, or as flaky as pop psychology. I was free to read.

This freedom has been slowly slipping away. When the furor over Midnight’s Children erupted in 1989, I became acutely aware that it would be impossible for me to read Rushdie’s book without a mountain of someone else’s baggage. I didn’t want to see Rushdie’s face, hear his voice or rerun a myriad of TV images showing incensed book-burning crowds when I read his novel. To this day, I have never even looked at it.

With contemporary literature, it became increasingly difficult for me to separate the author from the work because, in the real world, the author’s brand and personality were energetically for sale long before any new text hit the market. Increasingly, my first introduction to any contemporary author was through media representations of them, rather than anything they had written.

Then came the technology and the Internet; and they exacerbated the problem a thousandfold. Today, literary agents and publishers openly court celebrity authors not for their words; for their skill at constructing extended prose, but for their face or the way their backstories reflect contentious cultural issues. In the end my reading experience became dominated by headshots and personalities, news stories and publishing trends, even by people I knew personally; until I lost that essential freedom to read just the words in front of me.

There are, of course, critical approaches that rely on overlaying a framework of shared beliefs and predispositions onto a text. They all share the same profound weakness. They insist you regard the author’s own words as subordinate to the shared approach. All critical theories promise to act as a lens that can illuminate or enrich your private response to the author’s words, but they never deliver. Instead they act as a filter that subdues or eradicates anything that does not conform to the theory. This widespread way of reading, nurtured in universities and even now in schools, has led inevitably to the renewal of the perverse idea that books can be unsuitable or even harmful; and has fuelled the warped thinking of decolonisers and the censorious. My professional network is full of people who read like this. It’s time to rethink the way we read.

Much of my professional work in the last two decades has demanded reading a lot of academic research, in two disparate fields: poetry and educational research. There is the scholarly research necessary to write books about poetry and individual poets and there is work on educational research and development internationally. There is such a fast turnover of the latter, from such a wide range of sources, and the quality is so variable that I quickly learned to investigate the researchers and organisations before engaging with the texts themselves. I’ve saved myself innumerable hours of wasted effort by this simple strategy.

Nine times out of ten, you can find out what any given piece of educational research is likely to conclude just by researching the author’s background. Technology makes this research easier because there are so many different spaces where information about a researcher resides and so much of their success is bound up in being widely publicised, plus they are rarely timid about expressing their opinions. That bio on their university page is almost certainly going to spell their predilections out. You can apply the same strategy in literary criticism, but it’s much less immediately rewarding.

All this professional reading has taken place simultaneously with my own private reading of the articles and books I choose selfishly if you like, to read. But my pragmatic approach to professional reading has been undermining all my reading. When someone alerts me to a new book, essay, or article, I first take into account what I know about the author or publication, before committing myself to the material itself. Even when I decided, a few months ago, to read some Sir Walter Scott, I found myself reading about the man and his work first. I can still see the blonde, curiously cherubic image from the famous Sir Henry Raeburn portrait of him which I came across online. If I choose to read any more of his novels in future, I know it will accompany me—yet I wish it wouldn’t.

I understand why Italian author Elena Ferrante chose anonymity, preferring to let her words speak for themselves without a sultry headshot adorning a book cover, or an edgy interview driving sales. The words should always speak for themselves. As she puts it:

I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors. If they have something to say, they will sooner or later find readers; if not, they won’t… I do not intend to do anything… that might involve the public engagement of me personally. I’ve already done enough for this long story: I wrote it. If the book is worth anything, that should be sufficient.

In the same letter, she refers to “those mysterious volumes, both ancient and modern, that have no definite author but have had and continue to have an intense life of their own.” It’s indicative of how much writing is determined by the technology used in its production that the several failed attempts to identify Ferrante have taken place largely online, where the whole contemporary debate about what constitutes a fake currently resides. Technology doesn’t like anonymity. If you use a computer to generate words, it will afford you every imaginable opportunity to adorn them with additional information about yourself. Beneath every computer keyboard lies a hidden stream of data that potentially links the machine to every other machine; that remembers everything it’s told and that invites every user to commoditise themselves.

So I’ve started to cultivate an entirely new way of reading, a way that enables me to recover some of that essential purity I enjoyed before the world changed.

Before I make a conscious decision to read something, I think through precisely why I would want to read it in the first place. Professionally, the decision is usually entirely pragmatic. It involves thinking about and often researching the source of the material, then making judgements about how closely it meets the particular task in hand, which often includes an equation that takes into account the time required offset against the potential professional value. One question in particular proves extremely useful before reading. I always ask myself, is this likely to be something I may think highly enough of, to share with my professional network? It’s a question that has helped me strip my reading down to a much more manageable level and more often than not, does indeed lead to my sharing material as a result. All of this thinking allows me to recalibrate anything I decide to read as isolated and self-determining prose. By the time I start actually reading, I know that the next few minutes or possibly hours, can be devoted entirely to the words in front of me.

In the private domain, that selfish space where I’m reading for reasons that have nothing to do with professional demands, which is also highly likely to include fiction and poetry, as well as a greater proportion of printed works; thinking through why I would want to read something is a far from pragmatic exercise. I never, for example, ask myself, is this something I would share? Instead I ask, is this something I’m likely to enjoy and gain from? Answering that might well involve thinking about my previous experiences with the author, but now it never includes any active research. I’m far more likely to ask myself, what is it about this author I might need to put aside?, than what is it I need to remember?

This strategy allows me to separate the process of choosing from the process of reading. It wipes clean my reading palette. By the time I turn that first page or click on a chosen window, I’ve successfully realigned my relationship with the words on the page or screen. I now read only what’s in front of me again, so that I can hear what is said much more clearly. I am gradually beginning to rediscover all those invisible authors and consequently, most significantly of all, I am also—a much better reader.