Canada

R.M. Vaughan (1965–2020): A Beautiful Mind Silently Extinguished in a Time of Fear

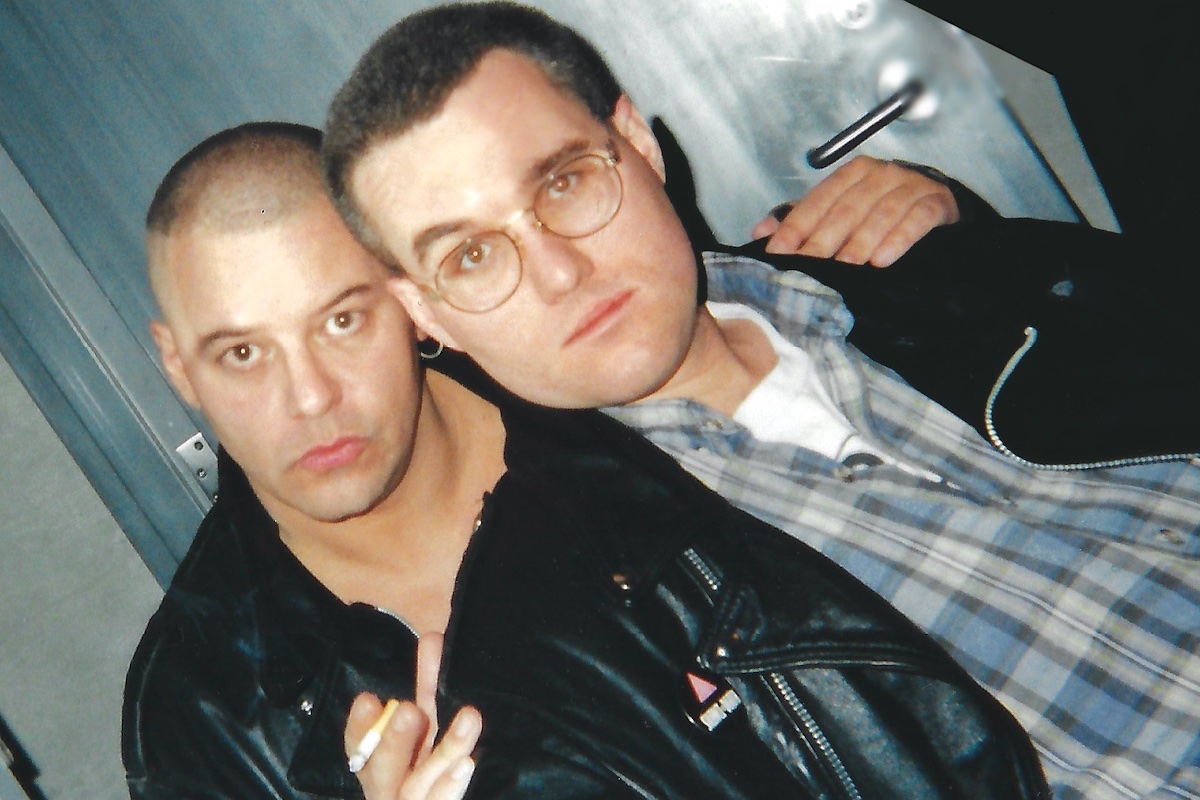

We were Oscar Wilde’s great-grand-nephews, dandy aesthetes obsessed as much with the curl of our hair as with art or politics.

We were extremely close for about five years. He was my confidante and my support system. We were best friends. Never lovers—though many thought we were. It was a dark time for me, and I needed him.

Canadian gay writer Richard Murray Vaughan (1965–2020) was found dead by police in Fredericton, New Brunswick on October 23rd—10 days after being reported missing. No foul play is suspected. This is in part a remembrance of R.M. (as he was widely known, including to his friends), but also a reminder that the campaign against COVID-19 can create its own kind of harm. I don’t pretend that this essay is one Richard would have authored (though he did write about COVID-19 and mental health shortly before his death). He and I were different men and different writers. But I do think my old friend would have agreed with at least some of what I have to say.

I met Richard when he entered my office at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre—142 George Street, Toronto—in 1991. Initially we talked about identity politics, though I’m not sure anyone then called it that. I could immediately see we shared something else, too—not just gayness, but effeminacy. We were Oscar Wilde’s great-grand-nephews, dandy aesthetes obsessed as much with the curl of our hair as with art or politics, “gayer than the day” as the expression went. “I’m from down east,” he said (meaning Saint John, New Brunswick, on Canada’s Atlantic coast). “And you must produce my work.”

He explained that he’d been the object of cultural oppression, that he didn’t stand a chance of having his gay plays produced in his native province (then, as now, a more conservative place than most of Canada). I was the artistic director of Toronto’s first and only professional gay theatre. It seemed I had little choice.

I produced (or had a hand in developing) several of Richard’s plays at Buddies, including Camera, Woman—about 1930s-era lesbian filmmaker Dorothy Arzner (who at one time was Hollywood’s only female director). I produced Richard’s work not only because he happened to be a gay man with few other options, but because he was enormously talented. At Buddies, I wasn’t terribly concerned about an artist’s identity; it was about the work. In those days, that was something you could say and mean. I produced lots of straight writers, and ignored the gay men who fancied themselves the second coming of Noël Coward. Richard’s work challenged me—just as the playwright himself challenged the directors and actors who brought his words to the stage.

And I loved him. It’s a fairly common thing, this platonic love between two effeminate gay men. We were sisters of a sort, sharing sex stories and romantic obsessions. We were both highly promiscuous and loved to shock. Richard didn’t talk about his family much; but I imagine his upbringing was as uptight as mine. Unlike me, he was adopted. And though he loved his mother, the relationship was difficult. Either she or his adoptive father (I can’t remember which) was descended from MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer (who grew up in New Brunswick after his Jewish family fled anti-Semitism in Belarus). This made sense, because R.M. Vaughan was known to affect the airs of a movie star.

We shared a deep contempt for what, at the time, I labelled “sweater fags”—uptight gay men who wanted to look and act straight; and who supported organized religion, gay marriage, and other forms of straight “assimilation.” We loved gay culture: drag, camp, s/m sex—and every alternative to monogamy. At the time, the AIDS crisis had caused many gay men to stigmatize sexual flamboyancy, and I was then under fire from my own community for being both promiscuous and a drag queen. (Three decades later, I am under fire once again for more or less the same type of behaviour, though for reasons connected more with academic theories of gender than actual sex.)

After I left Buddies, our friendship dwindled—nearly to nothing. I fell in love with a beautiful young man who became my partner. R.M. eventually moved to Berlin. I didn’t hear much from him—though he continued to support me, my career, and my public stands on pretty well anything. We were still sisters at heart. We had an argument before he went to Germany because he kept cancelling our luncheon dates due to illness. He was angry with me because I wouldn’t accept illness as an excuse.

That’s the heart of the matter, which I didn’t adequately appreciate. R.M. did have an illness. He was mentally ill. When I met him, he was already taking medication. Richard wouldn’t have a drink with me because of the pills. But he never told me what his diagnosis was, or what the pills were. I joke that when Richard came to Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, he came to the right place.

In 2020, nominally avant-garde theatre—including its LGBT forms—tends to be risk-averse and conservative, because political considerations require that no one be offended by anything. When I ran Buddies from 1979 to 1997, by contrast, it was something of an insane asylum. We believed the act of artistic creation was, in some ways, equivalent to madness. We were much in the tradition of surrealist poet Antonin Artaud’s “Theatre of Cruelty,” and believed as Shakespeare tells us, The lunatic, the lover and the poet / Are of imagination all compact. But many of the artists I supported—most, I believe—had real mental-health issues. Studies show that the brain functions of highly creative people sometimes mimic those of schizophrenics: In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, psychologist Julian Jaynes contended that both are blessed with the ability to hear ancient prophetic voices. And my own anecdotal experience is that real artists tend to be in touch with irrational, sometimes frightening, forces that the rest of us ignore or repress.

That approach to art is now impossible, as many playhouses have dedicated themselves to dreary lectures on the environment or identity politics. Writers are expected to be boringly sane, and often have characters speaking in the language of slogans and hashtags. The goal is to tell the audience what the audience already thinks they’re supposed to approve of. It’s the opposite of art.

For many real artists, art is the thing that keeps you sane. I think that was the case for Richard. Even in his heyday, things were hard. But now imagine what it was like in more recent years. His talent was bold and expansive. He wrote poetry, plays, novels, and essays, appropriating what he pleased and refusing to stay in his lane. Being adopted, gay, effeminate, and suffering from poor mental health, he lacked “privilege” in all sorts of ways. When R.M. first appeared in my office, it was still fashionable to be a gay writer. Today, his preferred male pronoun would be considered old-fashioned.

This is the level on which artists are now judged. Get creative with the government paperwork, and you might be able to receive some money earmarked for artists with disabilities. But the poetry of a lunatic aesthete is inevitably going to cause microaggressions. No artistic director wants that headache.

Then came COVID-19. Theatre has effectively ended. People can post all the Zoom performances they want—but nobody watches them because they are not theatre. Before the pandemic, the theatre world had been moving toward becoming more “immersive.” Influential theorists such as Philip Auslander and Jordan Tannahill wrote that theatre is about liveness, about human beings being in the same room in real time—the opposite of YouTube and Netflix. R.M. himself was not only a talented playwright, but also a magnificent spoken-word artist. His poems were funny as much as shocking. He made the room electric. That was his power source. And when COVID-19 closed the theatres, that light went out.

Despite the restrictions imposed during the pandemic, I thought I might see Richard on one of my trips to Montreal. (Over the summer, “gay Montreal” was less locked down than its Toronto counterpart.) But R.W. was being extremely cautious. He’d recently been appointed writer-in-residence at his alma mater—the University of New Brunswick. So he decided to remain in his home province.

COVID-19 is a deadly disease. But still, I didn’t understand why Richard was being so mortally fearful. I learned from AIDS that you cannot live completely in fear. And I thought that Richard might have learned that, too. In my mind, I accused him of being paranoid.

But then again, we have all effectively been ordered to live in fear. Fear is the new prophylactic, the new abstinence, the new self-censorship.

The daily dose of terror comes at a price—especially for those with fragile mental health, or who rely on human contact for a reason to go on. Or both. I like to think we can be made to understand the facts of how COVID-19 spreads without also being dressed down with legal threats and scathing moralism. But many government officials apparently believe otherwise. Winter is coming, and many will face it alone. Public health officials are telling us to fear the next few months, which will be “difficult” and even “dark.” Some of the people listening will conclude that it isn’t worth waiting for spring.

To some, R.M. Vaughan was just another privileged white, male artist. Others may think, Do we need more plays, novels, and poems about the “love that won’t shut up?” I think R.M.’s death reaches even beyond issues of sexuality and race. It speaks to a culture of exclusion administered by the brutally sane.