Activism

How We Lost Our Way on Human Rights

Surely we should seek to build on the past where possible, improve upon it, and learn from its successes as much as its failures—to create a healthy and honest partnership between past and present as a foundation for our future.

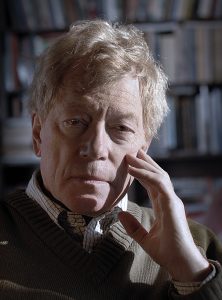

Sir Roger Scruton died on January 12th. He was a philosopher, public intellectual, provocateur, novelist, composer, lawyer, organist, and Fellow of The British Academy. Scruton wrote more than 50 books, as well as countless literary articles and journalistic columns. His work attracted opprobrium—but also much admiration.

In 2017, I joined a small gaggle of admirers from around the world for 10 days of philosophizing with Sir Roger. At the time, I had recently left my position in university administration and teaching politics to work as CEO of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. We attended seminars and excursions, and typically ended our days with hours of conversation over long dinners and musical performances. One afternoon, I found myself alone with our host in his study. Scruton, as I was already aware, was skeptical of the direction in which the human-rights movement was headed. He agreed wholeheartedly with what others would call first-generation human rights—in his terms, “claims for liberty” drawn from natural law. In particular, he defended the idea of individual agency, which invited a wall of rights protecting individuals from the encroachments of state and society. He contrasted these “negative” rights with claimed rights that are associated with the pursuit of equality and social justice. What distinguishes such claimed rights, he argued, is that they depend on positive actions from state actors—often on behalf of groups instead of individuals—rather than the right to be free of state encroachments. In many cases, positive rights are effectively political demands that are expressed in the borrowed language of human rights.

This put me on the defensive, as the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (like Canadian political and academic culture more generally) tends to embrace the idea of human rights in their maximalist form. I drew from Michael Ignatieff’s 2007 book, The Rights Revolution, in which the Canadian scholar wrote that “to believe in rights is to believe in defending difference”—and so defending human rights required governments to protect “the ceaseless elaboration of disguises, affirmations, identities, and claims, at once individually and collectively.” My appeal to Scruton highlighted our mutual belief that individual liberty rights were natural rights. But I also expressed the aspiration—which Scruton did not share—that, so long as members of a society exhibited a shared commitment to tolerate their differences, claimed rights (or “positive rights”) could be reconciled with their natural counterparts.

My optimism reflected the aspirational formulation expressed by Canadian and international courts: All rights are indivisible, interrelated, interdependent, even if it requires effort and imagination to reconcile them. Indeed, I had persuaded myself that the public-education efforts I was helping to lead at the museum—focusing on disparate lived experiences, human-rights heroes of the past, and the history of rights violations in Canada and elsewhere—were part of this important project.

While I had (mostly) persuaded myself, I failed to persuade Scruton. His response was predictably gracious, but he also warned that while the effort I had described may be admirable, “you will yet fail.” Our time was cut short before he could explain his position more fully. Yet I knew that his reasoning was informed by his own experience being repudiated, and even vilified, according to the shifting ideological tides he’d witnessed. He understood that the noble idea of defending difference requires a permanent good-faith commitment from all parties that they will respect the values of others, even when those values are seen as unpopular. Such a requirement was at odds with the real world he’d witnessed. It may even be in conflict with human nature itself.

Even before the advent of today’s social-media-fueled culture war, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) had already faced the challenge of navigating competing rights claims. The idea for the museum originated two decades ago with Israel Asper (1932–2003), a prominent media magnate and Canadian patriot who was seeking to create a Winnipeg landmark that celebrated common Canadian values. The momentum for the project survived his death, thanks to strong private and local government support, eventually leading to the federal government adopting the project by an act of legislation in 2008. Six years later, the museum opened its doors.

The ambitious nature of the project was encoded in the museum’s very name, and gave some Canadians an impression that the museum would be explicitly devoted to human-rights advocacy. This, in turn, led to contention about which specific rights claims should be pushed, and in what priority. Few noticed that the museum’s legislated mandate was limited: to preserve and promote Canada’s heritage, to contribute to Canada’s collective memory and sense of identity, and to explore the subject of human rights in order to enhance public understanding, promote respect for others, and encourage reflection and dialogue.

Much of the museum’s methodology hinges on the concept of dialogue. In his 1996 book, On Dialogue, David Bohm noted that the purpose of dialogue is not to argue with, critique, or undermine another’s perspective, but instead to suspend one’s own opinion and actively engage in listening as a way to understand the perspectives of others. Dialogue pursued in this manner leads not to debate but to shared meaning, which aligns well with the museum’s mandate to contribute to collective memory, and to promote respect for others. An institutional commitment to dialogue requires less in the way of advocating particular interests and rights claims, and more in the way of collecting and sharing lived experiences that are part of our common heritage related to human rights. This, in turn, may facilitate efforts to balance different rights claims.

But, as Scruton tried to warn me, such balancing presupposes some commitment among individuals to defend the right to disagree. One Canadian, for example, may value property rights as a fundamental right and at the same time recognize that his or her neighbor may prioritize environmental rights. Or another Canadian may believe freedom of speech to be an absolute freedom, while a second might believe strongly in a need for restrictions. Inasmuch as there are enduring commitments to respect such different values and priorities, there are opportunities to negotiate balance among competing claims. Without that commitment, on the other hand, we get a never-ending zero-sum competition to assert or reassert a hierarchy of rights, an approach hardly in harmony with the principle that all rights are meant to be indivisible, interrelated, and interdependent.

In its early years, the CMHR wrestled with how to pursue its formal mandate while dealing with internal and external expectations, a process that led some observers to describe its work as a “Pandora’s box of irreconcilable traumatic memory competition,” or an “oppression Olympics.” The CMHR didn’t want to become embroiled in debates about which atrocity was the most horrific, or which rights claim had priority over others. It instead wanted to promote a holistic conception of human rights, in keeping with the large banners that dominate two walls within the museum, quoting Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

While the media treatment of the CMHR was dominated by criticism of proposed exhibits, with members of some communities even comparing how much square footage would be allotted to which genocide, and the relative location within museum galleries, the museum stuck to its vision of the project. And since opening in 2014, I believe, the museum emerged as a trusted public resource for human-rights dialogue and education.

Until this year, at least. In June, following the same pattern that has played out at numerous other cultural institutions this past summer, the CMHR was hit with a wave of allegations on social media, with some former and current employees claiming that racism, heterosexism, sexism, and homophobia plagued the museum work environment. It was also claimed that the content of the museum had been censored in the past. The irony of a human-rights museum being subject to these kinds of allegations ensured that the claims received plenty of publicity. With my five-year term as CEO coming to an end in August, I chose not to seek a second term.

I’m not going to use this space to rebut specific allegations. Rather, I’d like to consider these events in light of Scruton’s warning to me back in 2017. What we are observing now is an ascendant movement that asserts social justice cannot be achieved unless we adhere to a specific hierarchy of identity rights and promote intolerance for anyone dissenting from that approach. This quite naturally has interfered with the project of balancing rights and fostering a universal commitment to defend difference. As noted above, this approach only works if this commitment is exhibited in good faith by all parties. Instead, many activists now encourage frenzied gestures aimed at toppling monuments and institutions perceived to be at odds, even symbolically, with their own narrow strategy for redeeming society from racism and other forms of ersatz original sin.

The idea of individual agency, which lay at the core of the case for traditional human rights, is now seen as part of the vernacular of oppression, as it interferes with the movement to separate people into racially defined categories. Likewise, the idea of dialogue rested on the idea of a shared language. Instead, we now are required to accede to the belief that we all inhabit mutually impenetrable realms marked by our identity, and that some of these realms confer special insight and intuitive powers that allow one to interpret and identify hidden meaning and concealed bias in the language of others.

Criticism can be just, of course. Yet if it is to have real political meaning, it must be delivered through the rational expression of opinion. As Jonathan Rauch has noted, cancel culture is the antithesis of dialogue. It consists of organizing or manipulating a communications environment so as to isolate, deplatform, or intimidate ideological opponents, and make them “socially radioactive.” There is no room for diversity of thought or viewpoints, and difference of opinion becomes a form of trespass. To disagree with the method is construed as a manifestation of bigotry.

No matter what one may think of this year’s controversies at the CMHR, there is no doubt that the means by which the claims have been prosecuted—a totalizing demand that any accusation of discrimination must be accepted at face value—is in direct conflict with the mandate of the museum and, for that matter, with the concept of human rights. Why would any museum, national or otherwise, having demonstrated its value in expanding public memory to include the lived experiences of different people across time and space, then adhere to a theory of social justice that requires it to be at war with the past?

Surely we should seek to build on the past where possible, improve upon it, and learn from its successes as much as its failures—to create a healthy and honest partnership between past and present as a foundation for our future. Such a partnership requires attention to all different generations of rights, as well as different perspectives on today’s struggle. It includes liberal perspectives, communitarian perspectives, conservative perspectives, libertarian, socialist, nationalist, spiritual, indigenous, religious, and secular cultural perspectives—a diversity of perspectives rather than allegiance to a singular, illiberal, gnostic perspective that rejects dialogue itself.

In such an intolerant environment, even those banners hanging on the walls of the museum quoting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights will seem toxic. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” risks sounding too much like “all lives matter.” Such are the wages of allowing particular interests to snuff out dialogue and pluralism.

In his own life, Sir Roger Scruton seemed to carry no enduring ill will against the legions of assailants who tried time and again to cancel his work. That his naysayers caused him injury is clear. Yet he remained committed to the principle of dignity and respect to all, regardless of their ideological convictions. His efforts to engage everyone in discussion and to demonstrate a lasting commitment to appreciate differences represent the measure of his character. They also show us how to deal with a culture of repudiation: through enduring commitments to friendship and charity, dignity and respect, and building bridges across difference.

That’s rarely the easiest route to follow, especially when others take a different path. Yet there’s no other way forward. And the need for more of us to hew to those principles represents one of the great moral challenges of our day.