Activism

Black Lives Matter and the Mechanics of Conformity

Left unrestrained, they can get completely out of hand. The sudden conformity produced by an availability cascade can result in reflexive demands for urgent government action without any proper discussion or consideration of trade-offs, consequences, or even necessity.

The death of George Floyd in May, circulated in a bystander’s excruciating video clip, reignited furious and sometimes violent protests demanding reforms to address police brutality against ethnic minorities. According to the Center for Police Equity’s 2016 report “The Science of Justice,” black Americans are disproportionately affected by the amount of force used against them by police, such as being tasered. Additional investigations have found that black suspects are more likely to be manhandled, pushed to the ground, handcuffed, threatened, or pushed against a wall during a police interaction than their white counterparts. Bias against the black community appears to extend in all kinds of directions, from the courtroom to the maternity ward, where black women are 10 times more likely than white women to have their newborn baby taken from them if they test positive for an illicit drug.

The apparently inequitable use of force against ethnic minorities, meanwhile, has unleashed a torrent of emotion and allegations against police departments across the United States in the wake of Floyd’s death, spurred on by celebrities and activists alike. Actress Julianne Moore and actor Aaron Paul joined other celebrities in a short film made in conjunction with the NAACP to protest “systemic bias.” Moore beseeches viewers to understand that, “Black people are being slaughtered in the streets, killed in their own homes,” to which, Paul adds: “Killer cops must be prosecuted, they are murderers. We can turn the tide, it’s time to take responsibility.” In an earlier celebrity video entitled “23 Ways You Could Be Killed In Black America,” Pharrell Williams, Alicia Keys, Rihanna, Chris Rock, Pink, and a litany of other celebrities describe 23 cases of black lives lost to police shootings in different scenarios, and demand “radical transformation to heal the long history of systemic racism so that all Americans have the equal right to live.”

Perceptions and data

But, for all their zealous advocacy, celebrities and protestors alike are reluctant to acknowledge or discuss the nuances of the empirical literature on the racial biases they are protesting. As part of an effort to quantify racial bias in police killings, a 2016 study in the journal Injury found that black Americans are not more likely to be injured or killed by police than white Americans during traffic stops. And, despite the general finding in the Center for Police Equity report that police officers use greater force against black suspects, it also found that blacks are no more likely than whites to be subject to lethal force. In fact, it found that white people face a higher risk of being killed during an arrest. Researchers have also turned their attention to shootings, in particular. An early study provides some evidence of a racial disparity, but not in the expected direction—it found that police fire more bullets at white than black suspects.

Things get even weirder when we try to probe psychological biases in police officers. Under multiple intense psychological simulation experiments carried out at Washington State University, police were found to exhibit a propensity to fire on white suspects faster than black suspects, and were also more likely to shoot unarmed whites (these experiments measure split second differences in reaction times that the researchers believe are not susceptible to conscious control). However, it is the work of economist Roland Fryer that has attracted the most attention and discussion of late.

Fryer emerged from a troubled past—he was abandoned by his parents and left to fend for himself on the street before becoming the youngest person in the history of Harvard to achieve tenure. Fryer has observed that, “A single bullet—which weighs about .02 pounds and is 10mm long—can end a life, erase a pension, or change the image of those who are sworn to serve and protect.” On the back of an earlier study that found unarmed blacks are at higher risk of a police shooting than unarmed whites, Fryer and his team came up with a more complete dataset and used an innovative methodology of comparing police interactions in which no shots were fired to those in which there were. His study arrived at a different conclusion. “The results are startling,” writes Fryer. “Blacks are 23.5 percent less likely to be shot by police, relative to whites, in an interaction.”

An obvious question arises—if black people are more likely to be roughly treated during an encounter with police, how is it possible that they are less likely to be killed? When a female Chicago police officer was beaten by a black man in 2016, she was asked in hospital by her superintendent why she didn’t draw her weapon and defend herself when she could have done so. “She looked at me and said she thought she was going to die, and she knew that she should shoot this guy. But she chose not to because she didn’t want her family or the department to have to go through the scrutiny the next day on national news.” While a white death at the hands of a police officer rarely makes headlines, a black death is likely to incite immediate media coverage, outrage, and protests or riots that last for weeks or months.

Researchers have hypothesized in an article for Criminology & Public Policy that the apparent “reverse racism” bias of police shootings reflects law enforcement fear of the consequences of a minority death, “the underlying causes of the reverse racism effect is rooted in people’s concerns about the social and legal consequences of shooting a member of a historically oppressed racial group. We believe that this, paired with the awareness of media backlash that follows an officer shooting a minority suspect, is the most plausible explanation.” The study on police shootings published by the National Academies of Sciences includes another finding that may make sense in this light—black police officers are more likely to shoot black suspects than white police officers are, perhaps because white officers will be subject to increased scrutiny following a fatality. The authors of the study conjecture, “The disparities in our data are consistent with selective de-policing, where officers are less likely to fatally shoot Black civilians for fear of public and legal reprisals.”

Before proceeding further, it’s important to emphasize caution on over-interpreting the anti-white findings of recent scholarship. The evidence on racial differences in police killings is not unambiguously settled; scholars continue to argue over the minutia of data collection and statistical techniques, and Fryer himself has warned against drawing strong conclusions at this stage: “Are there racial differences in the most extreme forms of police violence? The Southern boy in me says yes; the economist says we don’t know.” But uncertainty is sufficient to set off alarm bells about the Black Lives Matter movement among those who adopt a sceptical approach when evaluating knowledge claims. “There’s so much we don’t know,” says author Sam Harris in a recent podcast, “And yet, most people are behaving as though every important question was answered a long time ago.” Harris, known for his staunch atheism and critique of faith-based religion, asks some troubling questions about the Black Lives Matter movement by pointing out that it disguises empirically fragile claims with absolute conviction and then stonewalls any attempt to examine the evidence: “Like most religious awakenings, the movement does not show itself eager to make honest contact with reality.”

While doubt prevails among those familiar with the data on policing killings, faith-based inerrancy seems to invigorate activists to the point where discussion becomes futile. When video journalist Ami Horowitz tried to engage with Black Lives Matter activists he found they had virtually no familiarity with the data on police killings and no desire to know about it. “I can’t, I’m getting angry, I don’t want to talk anymore,” said one activist in response to Horowitz’s attempt to discuss the evidence. Another said, “Your data can go and suck the same dick you’re gonna suck.” Another rebuffed Horowitz by demanding to see his sources but then refused to look when he attempted to produce them on his phone. Yet another resorted to conspiracy theorizing, suggesting that any study conflicting with the sentiment of Black Lives Matter must be some kind of academic plot.

Much of this isn’t surprising given what we know about the psychology of political activists. After subjecting more than 10,000 people to knowledge-based questions about the state of the world, the late researcher Hans Rosling found that, on average, activists had a less accurate picture than the general public of the very issue to which their activism is devoted. In his book Factfulness he reports, “Almost every activist I have ever met, whether deliberately or, more likely, unknowingly, exaggerates the problem to which they have dedicated themselves.”1 Those with the most unrealistically dire and pessimistic view of any issue are those most likely to be motivated to do something about it. As Rosling points out, this makes activists the last people we should go to for an accurate understanding of the cause for which they are campaigning.

The informational cascade

It might seem incredible that conformity could manifest in the absence of supporting evidence, but the phenomenon of scientifically groundless belief enjoying mass acceptance is hardly new. In his paper “The Blind Leading the Blind,” David Hirshleifer describes a process of informational cascades, by which beliefs can spread through a population. Because it is costly in time and effort to master evidence involved in a variety of issues, most people base their beliefs on what others believe rather than on primary evidence, on the assumption that others are well informed. A snowballing effect then occurs as the validity of a belief increases along with the number of believers. The end result may be that everyone assumes that everyone else knows what they’re talking about: the blind leading the blind.

And, as likeminded people surround each other, the more resistant they are to discrediting information. Leon Festinger describes this process in When Prophecy Fails, but the most eloquent description comes from Adolf Hitler’s architect and Minister of Armaments Albert Speer, who spent decades in prison after the war attempting to understand how he had allowed himself to become swept up by the delusions of the regime he supported:

… in normal circumstances people who turn their backs on reality are soon set straight by the mockery and criticism of those around them, which makes them aware they have lost credibility. In the Third Reich, there were no such correctives, especially for those who belonged to the upper stratum. On the contrary, every self-deception was multiplied in a hall of distorting mirrors, becoming a repeatedly confirmed picture of a fantastical dream world, which no longer bore any relationship to the grim outside world. In those mirrors I could see nothing but my own face reproduced many times over.2

Just as sticks propped against one another are kept upright by mutual inter-dependence, false beliefs may acquire spurious validity in the public square from the confidence engendered by their popularity. When one is brought up in a society where everybody practises a religion, there is scarcely any reason to question that religion, even though it may have no contact with reality at all. Over the past few months, I’ve asked friends and acquaintances if they believe in an epidemic of killings by police, and if so how they came to believe this. I tended to receive answers such as “everyone knows,” or “literally nobody disagrees.” These are the words of believers who have relied on cues from their peers to form the belief.

Informational cascades are then reinforced as they interlink with our psychological biases and other social mechanisms. I recently saw a particularly vehement Black Lives Matter supporter berating another in an online community forum for the crime of remarking that “all lives matter”: “Black Lives are getting snuffed out of this world by the very law enforcement officers who swore an oath to protect them… All Lives Matter can get fucked as far as I’m concerned.” When I asked her how she came by this belief, she cited “the countless videos that people are uploading of innocent black people suffering at the hands of law enforcement officers.”

The availability cascade

In the 1960s and 1970s, the behavioural scientists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman began studying the mental shortcuts that inform our psychological judgements, and termed one of these shortcuts the “availability heuristic.” Tversky and Kahneman found that the ease with which specific instances of a thing can be recalled, the more likely we are to overestimate the importance and frequency of that thing occurring. “People tend to assess the relative importance of issues by ease with which they are retrieved from memory,” writes Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. What is in our memory, he argues, “is largely determined by the extent of coverage in the media.”

Research carried out by Sarah Lichtenstein, Paul Slovic and Baruch Fischoff bears out this view. For example, the media pays a disproportionate amount of attention to deaths in tornados and accidents of all kinds compared to deaths by diseases such as asthma or diabetes. Lichtenstein and her colleagues found that people believe that accidents are 300 times more likely to kill someone than diabetes when in fact diabetes kills four times as many people as accidents. Tornadoes are thought to kill more people than asthma, even though asthma kills 20 times as many people. The implications of this availability heuristic and our media saturation of black deaths in police hands should be obvious. If the disproportionate media attention paid to tornadoes makes them seem hundreds of times more dangerous than they actually are, what are we to expect from the massive amount of media coverage devoted to black deaths at the hands of law enforcement?

“These videos will keep coming,” warns Sam Harris, “And the truth is, they could probably be matched two for one with videos of white people being killed by cops.” But why aren’t they? The media chooses to disproportionately report on black deaths for the same reason police officers have allowed themselves to be assaulted rather than fire their weapons at black attackers. Black deaths are far more likely to incite newsworthy protests and condemnation. Anger and civil unrest follows a black fatality because there is a widespread perception that an epidemic of black killings is occurring, a perception in turn influenced by our availability heuristic due to disproportionate coverage of black deaths in the media following earlier outrages.

In other words, the public and media have been amplifying one another in a self-reinforcing loop that economists Cass Sunstein and Tim Kuran call an availability cascade—media reporting influences the public, who communicate the idea among themselves and demand greater coverage from the media, which in turn influences us through the availability heuristic, producing further numbers of believers and greater demands for media coverage, and around the circle goes until everyone has wound themselves into a panic. Historical examples of panics caused by the media and public amplifying one another include epidemics of diseases, epidemics of drug use, and environmental scares. Informational cascades are one of the underlying mechanisms driving availability cascades—the more people who start believing in something the more that other people are convinced to believe the same.

Activists and journalists may not realize that they are catalysing an informational cascade when they make certain claims. As Sunstein and Kuran note, “they themselves are subject to the availability heuristic as much as everyone else, and the fact that they move in circles within which the claim seems to be believed may have convinced them about the existence of a tremendous risk.” In their foundational 1999 paper, Sunstein and Kuran note that public hysterias engendered by availability and informational cascades can begin with a kernel of truth that is then misunderstood by the public, or misrepresented by the media: “The information will often contain grains of truth, but it may also harbor biases, even outright fabrications.”

For instance, Pulitzer Prize finalist Ruth Marcus writes in the Washington Post that black men are “two and a half times more likely than white men to be killed by police.” This figure reflects the fact that the black population makes up 14 percent of the American population but 34 percent of fatalities at the hands of law enforcement. While these figures are correct, important context is missing. White Americans are twice as likely to be killed by police as Asian Americans after adjusting for population benchmarks, but this doesn’t reflect racism against whites—it reflects differing rates of criminality among whites and Asians.

Because white Americans are more likely to commit crime than Asian Americans, they are twice as likely to interact with police and to be killed while doing so. Black Americans are seven times more likely to commit murder as white Americans, and the majority of murders and robberies in the United States are carried out by black Americans even though they are a minority. Thirty-five percent of police officers are killed by a black offender. As Roland Fryer and other scholars are aware, levels of criminality are independent variables that must be controlled to determine the dependent variable under discussion—police violence motivated by racism. “Of course, black lives matter as much as any other lives,” wrote Fryer some years ago, “Yet, we do this principle a disservice if we do not adhere to strict standards of evidence and take at face value descriptive statistics that are consistent with our preconceived ideas.”

Susceptibility to informational and availability cascades varies according to an individual’s preconceived beliefs, levels of knowledge, intuitions, visions, values, and desires. Sunstein and Kuran call this arena of heterogeneous receptivity to influence an “availability market.” Just as buyers in an economic market vary in their receptivity to new and unproven products, in an availability market, people with different preconceived ideas vary as to whether or not they will “buy into” unsubstantiated beliefs. Catholics are far more likely than anyone else to buy into fantastic reports of a weeping statue of Mother Mary, and as Hans Rosling found, political activists are more likely to buy into radical claims that support their already systemically pessimistic beliefs.

The reputational cascade

So, poor reporting influences public opinion wherever preconceived visions provide an availability market for certain beliefs to grow. This increases the number of believers which gives rise to further informational cascade effects as those believers increase the influence on others, and so on. The public and the media may then become less willing to publicly challenge ascendant beliefs due to a social mechanism called a reputational cascade. Reputational cascades behave like informational cascades but the underlying motivation is different—people publicly embrace the beliefs of others out of social necessity rather than genuine belief. As a consensus emerges, the burden of justifying one’s beliefs falls on those who dissent from the prevailing orthodoxy, and as the prevalence of a belief grows, the costs of dissent increase causing a snowballing effect of preference falsification (publicly lying about what one really believes).

In Sunstein and Kuran’s framework, public figures may constitute a lucrative availability market due to their increased sensitivity to the reputational cascade. Over the past few months, we’ve seen corporations and businesses around the world trip over themselves to declare their support for Black Lives Matter, change the name or branding of their products, and even fire employees who have publicly dissented. Meanwhile, mayors, house speakers, and a prime minister have fallen to their knees in a gesture of support for the movement (without explicitly endorsing any of that movement’s claims). Celebrities and politicians may declare their allegiance to the cause owing to reputational concerns, but their voices, amplified by the media, increase the availability of the belief to others who may assume that their opinions must be properly informed and well supported if they are prepared to declare them in public. Before long, the idea that an epidemic of racially motivated police killings is underway has become an unchallengeable article of faith. Informational cascades and reputational cascades feed into and reinforce one another—both increase the number of people publicly confessing to a belief and thereby exert more influence on others to conform.

As hysteria rises and people everywhere become alarmed or pretend to be alarmed by whatever the imagined crisis is about, Sunstein and Kuran point out that historically the media systematically suppresses reasoned commentary by experts in the relevant field and may even give more attention to “gimmicks” that further inflame panic. According to Kahneman, “Scientists and others who try to dampen out the increasing fear and revulsion attract little attention, most of it is hostile: anyone who claims the danger is overstated is suspected of association in a heinous cover-up.”

Sendhil Mullainathan is one of Harvard’s most distinguished economists. Renowned for his work on racial discrimination, Mullainathan has argued in his own breakdown of the evidence that black deaths do not appear to be the result of a racial bias in policing: “What the data does suggest is that eliminating the biases of all police officers would do little to materially reduce the number of African American killings.” Mullainathan, however, does not appear to have been invited onto television to explain why Black Lives Matter activists have their facts wrong. Instead, activist children are paraded across our screens to tell us how afraid for their lives they are, and to instruct us in the reforms required of law enforcement.

The consequences of hysteria

Hysterical, unsubstantiated claims produced by availability cascades, such as the Love Canal toxic waste incident, may have driven scientific inquiry to reveal details that otherwise wouldn’t have come to public attention for decades. Perhaps the hysteria of recent months will incentivize scientists and governments to work harder on understanding police brutality—or perhaps it will destroy the scientific enterprise in this area. Historical evidence indicates that blacks really were targeted in police killings in decades past and that media and public amplification of the issue is part of the reason that this is no longer the case. Availability cascades, in other words, can arise from legitimate concerns and raise awareness to produce valuable change.

Difficulties arise when the social networking effects of a cascade continue once the problem at issue has been brought under control. Left unrestrained, they can get completely out of hand. The sudden conformity produced by an availability cascade can result in reflexive demands for urgent government action without any proper discussion or consideration of trade-offs, consequences, or even necessity. “The resulting mass delusions may last indefinitely,” write Sunstein and Kuran, “and they may produce wasteful or even detrimental laws and policies.” In the wake of George Floyd’s death, we have heard urgent calls from the media and the public to investigate and even abolish police departments, a sign that delusional beliefs have been allowed to run amok.

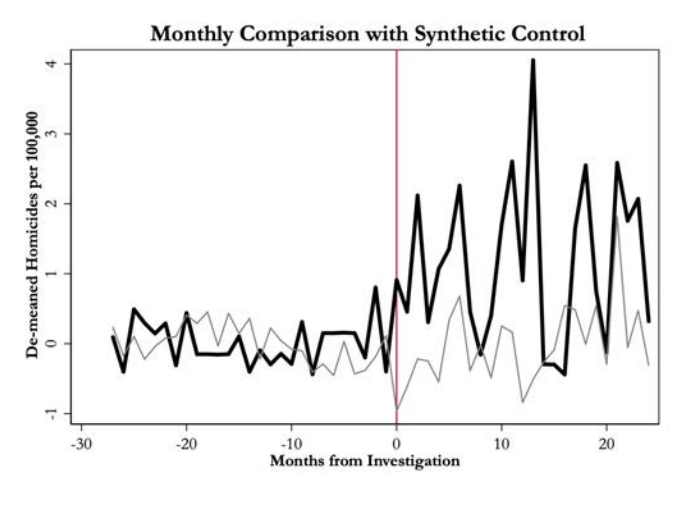

Investigations into alleged police misconduct are obviously important, but not when conducted in response to the histrionic demands of uninformed activists. A recent 50-page study examined the effects of investigations into police forces on crime. It found that most investigations are followed by a reduction in levels of crime, but with one important exception. If an investigation into the police force occurs after a viral media storm due to the shooting of a black suspect, the effect is a significant decrease in policing and a catastrophic increase in crime. The paper warns, “If the price of policing increases, officers are rational to retreat. And, retreating disproportionately costs black lives.”

The researchers measured crime in five cities after a black death at the hands of law enforcement caused a media storm and an investigation. They estimated that 900 additional deaths, most of which were black, were due to a withdrawal of policing, and that homicide rates remain higher for years before returning to baseline levels. So, under present circumstances, and contrary to the declared aims of the Black Lives Matter movement, we should prepare for an increase in black deaths—just not at the hands of the police.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this article contained the sentence “National Academies of Sciences published the findings of its investigations into police shootings in 2019, and cautiously concluded that white people are at greater risk of being shot during a police interaction relative to all other ethnicities.” This sentence has been removed because the investigation has been retracted by its authors. The investigation was also published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, not the National Academies of Sciences. Quillette regrets the error.

References:

1 Rosling, Hans, Rosling, Ola, Rosling, Anna, Factfulness, Flatiron Books (2018).

2 Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich, Orion (1970)