Activism

The Piety of the Impious

The largely ineradicable character of the religious instinct means that it persists, even upon the apparently disenchanted landscapes of modern secular culture.

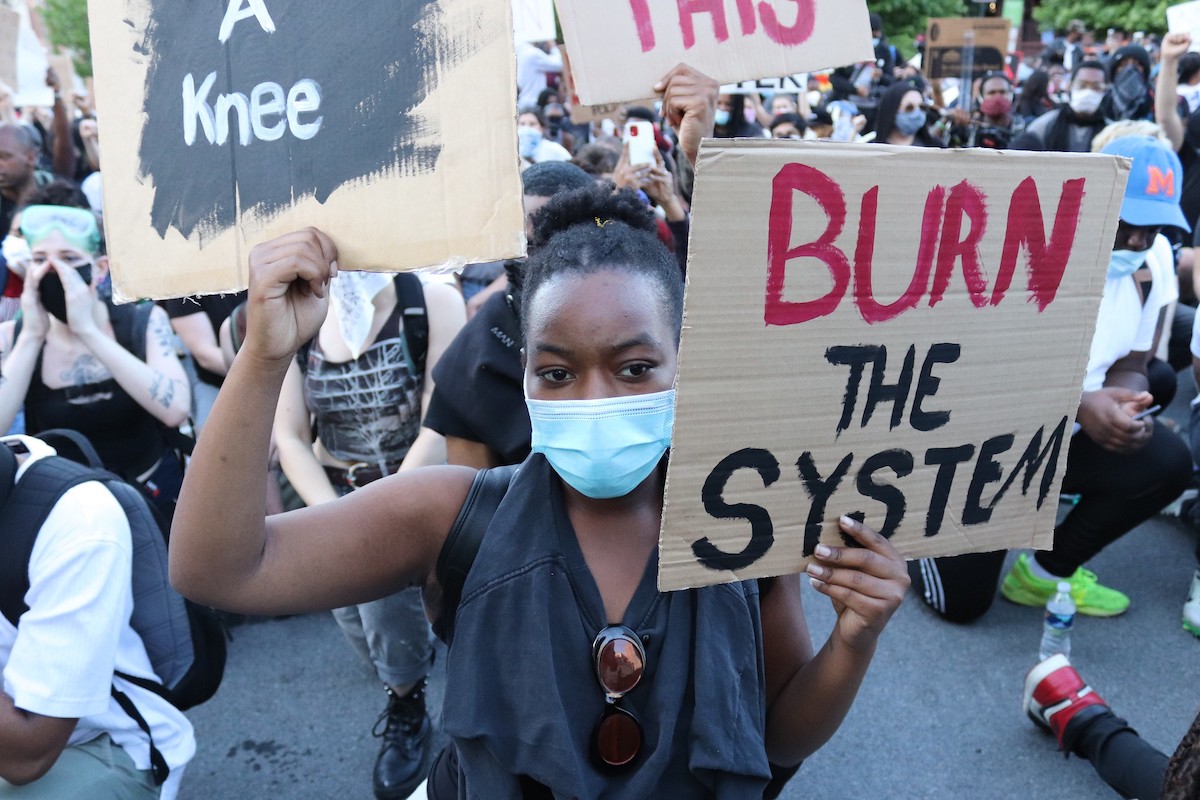

Writing with not a little insight, commentators have observed a deeply intriguing dimension to the protests currently convulsing the United States: Percolating beneath the callow progressivism lies a kind of spiritual fervour, which animates a great swathe of the demonstrators. It’s not simply the case that some people have been driven by prior religious convictions to respond to the killing of unarmed African Americans by police; rather, it’s that much of the outpouring of grief, activism, and even violence triggered by the death of George Floyd is itself quasi-religious in character.

Popular opinion holds that the United States remains a bastion of piety within the community of Western nations; although European states long ago settled into an easy secularism, the pulse of vital religion still beats strongly on the other side of the Atlantic. It’s true that the US remains an outlier in this regard, although the reality is far more complicated than common narratives suggest. Moreover, statistical evidence indicates that the country may be on the same trajectory towards secularisation as the Continent. But while America may be busily divesting itself of its religious inheritance, this hardly entails the erasure of all “spiritual” sentiment. On the contrary: that impulse persists, even if it is sometimes channelled differently.

From a certain perspective, this is unsurprising. The propensity of humans to devote themselves to comprehensive worldviews is nearly universal. We are a meaning-making species, prone to developing grand existential schemes as a way of buttressing our lives and integrating the sheer welter of events that daily confront us. More fundamentally, it represents an attempt to reconcile oneself with one’s own mortality and finitude.

The largely ineradicable character of the religious instinct means that it persists, even upon the apparently disenchanted landscapes of modern secular culture. Like nature, society abhors a vacuum. And with the demise of organised religion, other claimants have rushed in to fill the void.

Writers such as Tara Isabella Burton have documented the mushrooming of new movements and fashions, which in many ways ape the external features of traditional religious beliefs or practices. Politics is, of course, one such vehicle, supplying the meaning, values, solidarity, identity—even the pretence towards a type of salvation—that were once the preserve of organized religion. Ideological frameworks, whether past or present, offer a pre-packaged means of explaining the world and its ills, claiming to satisfy one’s craving for something beyond the individual and the material. In societies starved of conventional sources of spirituality, those systems—and the mass gatherings they may generate—offer something of a secularised substitute.

And so, we return to the present eruption. The activist zeal that has roiled America and elsewhere may express a yearning, however inchoate, for a kind of transcendence that has survived efforts to extirpate traditional religion from Western societies. True, not everyone involved in the recent protests is driven by such existential concerns; so diffuse and widespread a social movement will attract a conglomerate of participants. But for some, politics as a procedural, incremental, collective enterprise has given way to a deluge of righteous fervour, more akin to various expressions of religious fanaticism that have broken out periodically throughout history.

Witness some of the key moments that have emerged over the past couple of months. The toppling of statues has dominated news cycles, but it also provides a particularly clear window into the types of attitude that have colonised the minds of some activists. The philosopher John Gray has rightly termed these acts of iconoclastic destruction: “rituals of purification,” aimed at cleansing society at large, and consolidating the protagonists’ moral and spiritual virtue. It is a well-trodden path, one taken by a variety of groups spurred on by a profusion of religious zeal. As but one example, Gray cites the outburst of Anabaptist millenarianism in the wake of the Reformation: The obliteration of artistic and iconic works was part of a wider movement to (violently) wrench the present, and indeed the future, out of the ossified grip of a moribund past.

Certainly, such actions intersect with more mundane grievances. But this is politics in a cosmic key, focused upon an “eschatological horizon” that promises to trigger a wholesale break with the present course of history. As psychologist and ethicist Aaron Kheriaty has recently written, the iconoclasm on display manifests an effort to create the conditions for “an entirely new and historically unprecedented social order”—the secular analogue to traditional religious longings for the divine kingdom, whose advent would sweep away the moral detritus of both historical and current political systems.

The destruction of secular iconography in towns and cities across the US bears witness to this utopian desire for redemption—an emancipation from the past, which is seen as unbearably corrupt. In fact, it’s an attempt to realize that desire using the tools of political vandalism, which have been harnessed to overturn the sacred symbols of the old order. That the eschatological object of such longings remains opaque and ill-defined doesn’t diminish their potency.

What of other scenes now embedding themselves in popular imagination? Watching thousands of people “take the knee” (as if in prayer) or chant creeds in unison, one is struck by the spiritual quality of such actions. These aren’t merely protests; they, too, are near-sacred rituals, with all the liturgical trappings of a religious service. Although such gatherings occur in ostensibly secular spaces, they are festooned with sacral imagery (including a cloud of slain martyrs), sculpting and guiding participants at a deeply existential level.

Much of this bears more than a passing resemblance to Emil Durkheim’s concept of “collective effervescence,” which holds that the gathering of individuals in mass settings for a common purpose can engender a spiritual-like experience. With the right cocktail of social context, shared concerns, and corporate energy, participants may be drawn out of themselves into a higher realm of intense, collective excitement. The resulting emotional “electricity” is profoundly generative, creating a profusion of almost sacred meaning that transcends any one person. To observe the brewing protest marches, then, is to witness Durkheimian theory attain shape and body and life.

The protests constitute a key manifestation of the broader creed of anti-racism, which supplies them with whatever intellectual ballast they exhibit. Chief among the ideology’s claims is the totalising concept of structural or systemic racism. It’s true that sometimes unjust racial disparities are products of broader institutional mechanisms; both progressive and conservative voices have argued as much. But when a concept like structural racism is deployed axiomatically to explain every instance of racial disparity, no matter how minor or contrived, then we have moved away from sober discourse, and drifted instead into the realm of all-encompassing metaphysic—a fundamental theory—resembling the dogmatic architecture associated with popular religion.

Casting white supremacy and its crowning achievement, the institution of slavery, as America’s “original sin” functions in a similar manner. For certain advocates, white people bear within their own bodies the near-ineradicable marks of their ancestors’ primal fall—not that of the fabled Adam and Eve, but of the early whites who established and maintained the sordid trade in human flesh. The seeds of racism are said to lie in every white person, even those who explicitly repudiate any notion of racial superiority as a moral cancer. As John McWhorter has observed, activists have propounded the notion that white Americans are tarred with the legacy of their supposed privilege, from which absolution may be sought only through ceaseless rounds of contrition and repentance.

It’s easy to see how such views complement the utopian—and indeed, destructive—tendencies many protestors have revealed. If society is so riddled with injustice, then reforms, no matter how grand or ambitious, are likely to fail. Deconstruction is the only viable solution. Unwittingly, however, many anti-racist and black rights advocates help themselves to the same cultural patrimony they seek to dissolve. This should come as no surprise: Despite assiduous efforts to liberate themselves from history, protestors are, like everyone else, ensconced within it. Try as they might, they cannot avoid completely the overtures of the past.

Activists from Portland to Atlanta have unconsciously imbibed elements of America’s residual Christian legacy, earnestly recycling them within a post-Christian environment. Talk of white people being tarnished by the evils of their ancestors clearly transposes the biblical story of Man’s fall into a secular context. Similarly, the obvious eschatological overtones of the movement appropriate the cosmic and redemptive dimensions essential to the Christian religion.

But even in those convergences, differences remain, with the current movements mimicking some of the worst excesses of populist or millenarian religion (filled out with a noxious blend of warmed-over Marxism and modern identity politics). Universal sinfulness, for example, has been replaced by the accursedness of one particular ethnic group, in a strange inversion of the curse of Ham. Writing to the church in Rome during the first century, the apostle Paul declared that “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). It is a claim that Christianity has affirmed ever since. But modern anti-racists, both on the street and in the academy, have radically circumscribed the doctrine, applying it in a selective, highly racialized manner. Ignoring Solzhenitsyn’s warning that the line between good and evil cuts through every human heart, they have adopted a moral dualism that is fundamentally Manichean in attitude. Absent, too, are notions of forgiveness or charity, which Christianity, at its best, has greatly cherished. Merciless treatment is meted out to anyone who dissents from the protestors’ overarching values, or who isn’t sufficiently seized by the conviction that American society is incorrigibly racist. In their stead lies a purifying fanaticism, aimed at purging every view that fails to reflect the movement’s exacting standards.

And while the current demonstrations manifest a certain Christianised eschatology, protestors eschew the mainstream Christian belief that redemption is something that can only be secured extrinsically, as a result of God’s in-breaking kingdom. Instead, they cast themselves as the specially anointed agents of emancipation, leading the charge towards a claimed racial eschaton. A person doesn’t need to be a Christian to see the dangers inherent in such utopian schemes; a basic grasp of history is sufficient. The idea that flawed individuals can possibly wrought sweeping, epochal progress within the decrepit structures of history has been shown repeatedly to issue in the same injustices against which the vanguard claims to be fighting.

This witches’ brew offers up a potent series of dangers, especially in an anxious, highly fractious society. As Andrew Sullivan has noted, the quasi-religious character of both the protestors and their intellectual benefactors has already seen the substantial cessation of transparent debate around the issue of race, and the growth of an often-vicious intolerance. Thus, does the lifeblood of a healthy political community evaporate. When a political program is transcendentalized in the way this one has been—with only one perspective being imbued with near-cosmic urgency—attempts to explore a complex issue from the point of view of one’s opponents are repudiated as a dance with heresy. It is to debase oneself by engaging those who are regarded, not as fellow citizens with whom one disagrees, but as existential foes whose mere existence may retard the liberationist project.

Activists will be untroubled by all of this, salved as they are by the righteous demands of their cause. And yet, they are creating the conditions for precisely the kind of coarse, pitiless society they profess to oppose. Witnessing many of the protest marches, or hearing the self-appointed priests of the anti-racist creed, is to glimpse a dark future. It’s a future in which charity towards the other is condemned, violence is valorised as a crucial instrument of progress, and the crushing of all dissent is lauded as a sign of ideological virtue. In short, it’s a future stripped of everything that ordinary, decent folk seek in fashioning a life for themselves and their loved ones. The urban acolytes currently dominating news feeds tout their penetrating insight into the ills plaguing society. But by their actions they reveal the narrowness of their vision, and the bitter harvest of so much chiliastic idealism.