Books

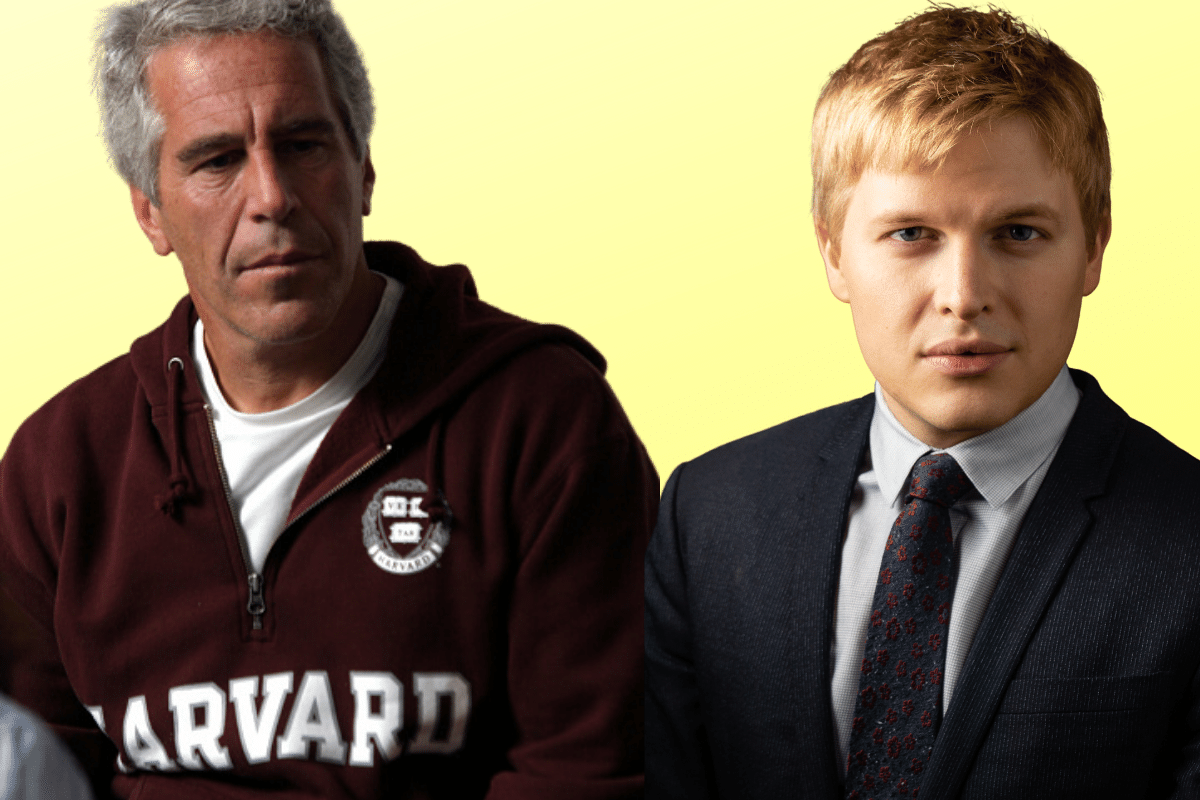

Jeffrey Epstein's Money Tainted My Workplace. Then Ronan Farrow's Botched Reporting Trashed My Reputation

The New Yorker story remains an albatross around my neck.

“You really need to pull over. You can’t drive all the way to Illinois without some rest,” my spouse implored, as he tried to speak sense to me on the phone while looking online for hotels in Eastern Pennsylvania. I could stop in Bethlehem, he said without irony. He had found a Hampton Inn that looked nice. It was already one in the morning.

But I didn’t stop. I didn’t want to. I wasn’t tired and I couldn’t bear the thought of it. I didn’t want to wake up in some chain hotel and see my picture on five different TVs in the breakfast room. I kept on driving.

Earlier that evening, the night of Sunday, September 8th, 2019, I’d run into my apartment building near the Brown University campus in Providence, Rhode Island, and grabbed my clothes, a toothbrush, some deodorant, and my house plants—all the stuff I thought I’d want to have with me over the next few weeks. I jammed everything into my 2005 Corolla for the drive to Illinois. It was 9pm, not an ideal time to start a long drive. But my story had already appeared on the Providence Journal website, and I didn’t want to be in town when the actual papers were delivered the next morning.

Brown University, my employer and alma mater, had put me on paid administrative leave that afternoon while it investigated any role I may have played, years earlier, in a sideshow to the larger Jeffrey Epstein scandal. On September 6th, star New Yorker reporter Ronan Farrow had published confidential emails about the disgraced financier’s lengthy history as donor and visitor to the famed Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, MA, where I’d previously worked. Farrow’s source for these emails had been my junior colleague at the Media Lab, a development associate named Signe Swenson, whom I’d routinely cc’d on matters related to donors.

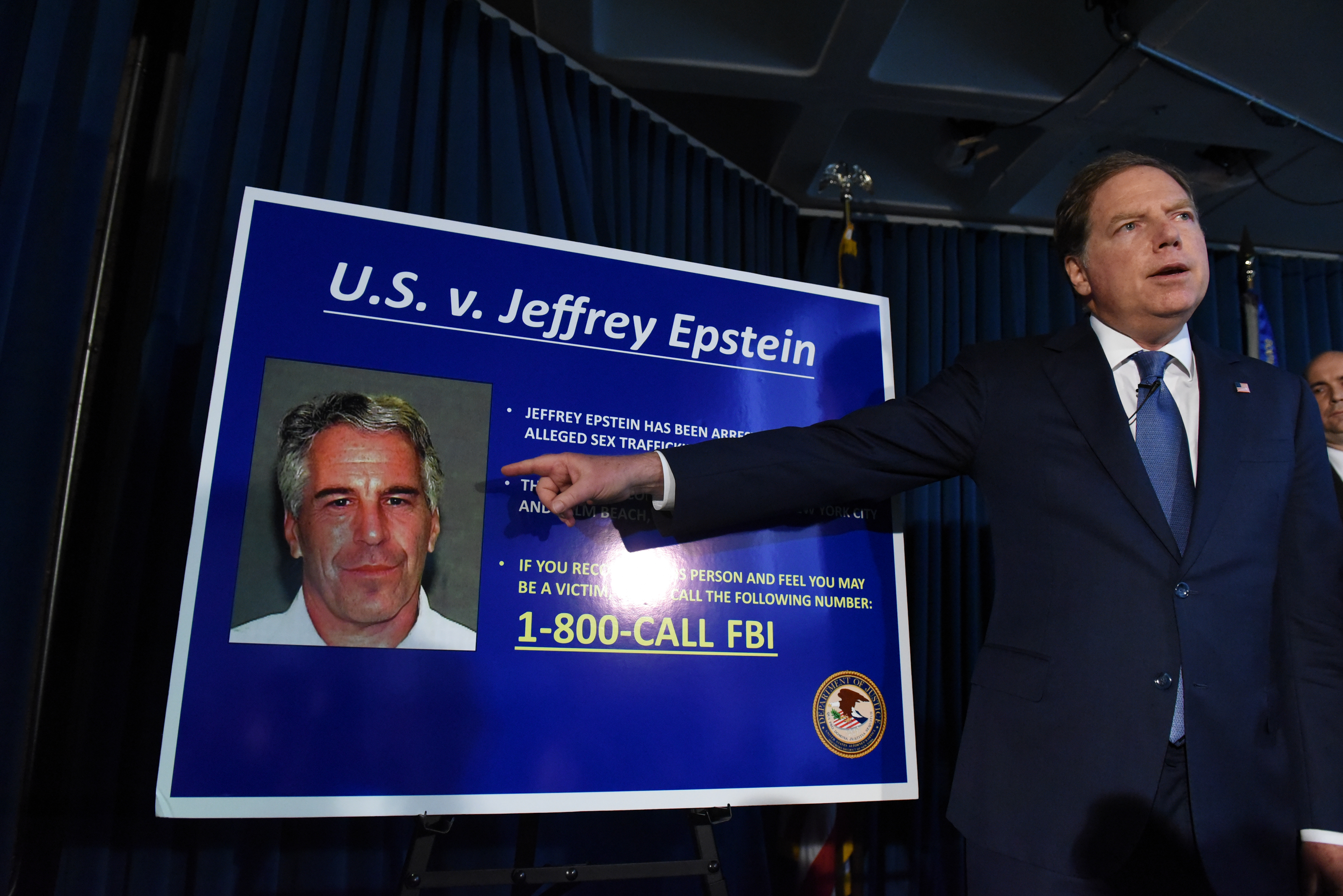

I never made any of the decisions about Epstein’s donations. And I was never accused of breaking any of the university’s rules, as would be made clear in the official January 10th, 2020, report produced by a team of outside lawyers commissioned by MIT to investigate Epstein’s extensive relationship with the Media Lab. As anyone who reads that (publicly available) 61-page report will see, my role in the investigated events was relatively minor. Its authors, focused understandably on the real decision-makers at MIT, didn’t even mention me by name, only by job title. (The official name of the document is Report Concerning Jeffrey Epstein’s Interactions with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But I will be referring to it simply as “the MIT report.”)

Yet because my name happened to appear at the top of emails that Farrow looked at, the New Yorker reporter chose to assign me a co-starring role in the narrative he spun. As the MIT report would make abundantly clear, Farrow botched major details of that narrative, and his errors would become embedded in the version of events related by other journalists. When the Providence Journal ran its story, for instance, it was titled, “Brown University director with ties to Jeffrey Epstein placed on leave.” Nine months later, the mistakes contained in that initial round of reporting continue to impact my personal and professional reputation, thanks to Google and the esteemed status of the New Yorker.

As I drove west into the night, my phone was popping with inquiries from reporters around the country. I didn’t respond, instead forwarding these requests to a lawyer I’d never met, and whom I wouldn’t even speak to until Monday afternoon. In Connecticut, I stopped to get gas and called a friend who worked at Brown. Later, she would say it was the first time she’d really been worried about me. I sounded unhinged, she said. And I was. I couldn’t understand how I’d joined Donald Trump, Bill Clinton, Prince Andrew, Les Wexner, and other famous men caught up in the Epstein scandal. I wasn’t powerful or rich. I wasn’t even straight. What was clear was that there was no way I was going to remain in Providence, where I’d run into colleagues on the street. My spouse lived in Illinois, and I planned to join him there.

I had never driven overnight before. I learned that it’s easy to go very fast when everyone else is asleep. In the morning, when the police were patrolling in greater numbers, I got a speeding ticket outside Pittsburgh. The drive through Ohio ended up feeling much longer than it looked on the map, made worse by a two-hour stop outside of Columbus, first to talk with a dear friend who wanted me to confide in a reporter, and then to speak for the first time with my new lawyers, Nancy and Brian.

I arrived at our house in central Illinois around 7pm, exhausted but also wired. The car was filthy, I needed a shower, the plants had largely survived. Little did I know, I had another 123 days before MIT would release its report.

Between January 2014 and March 2017, I worked at the MIT Media Lab as its director of development and strategy, a euphemistic title for someone who helps raise money from donors. (I also did some minor paid consulting work for the Media Lab from October to December 2013, which was after they’d hired me but before I officially started. All of that work was conducted off-site, and none of it involved Epstein.) At first, I reported directly to Media Lab Director Joi Ito, whose close ties to Epstein would in time become well known. In the Fall of 2015, I was asked to report to the Lab COO, Barak Berkowitz, as it was clear that Ito had little interest in directly managing my position. But my job didn’t really change.

From the beginning, I was an unlikely fit for the Media Lab. Far from being a tech enthusiast, I am the guy who’d have to call home for tips on how to use his own computer. (At the Lab, I was the only person on staff with a PC, while everyone else had shiny MacBooks.) I wore ties during trips to Silicon Valley and in the office, to everyone’s befuddlement. It was my way of being a contrarian in a sea of tech-world athleisurewear and untucked shirts. I got the job because I had fundraising experience and had worked at Carnegie Mellon, another tech powerhouse. And MIT was considered a prestigious gig: years later, I would get my job at Brown as the fundraiser for computer and data science precisely because I’d worked at the Media Lab.

As for the Lab itself, “all icing, no cake” is what a lot of the top scientists and engineers at MIT used to say about it: great PR, but mostly fluff. Personally, I thought that about half of what was done at the Media Lab while I was there was serious science and engineering. The rest, not so much. Companies paid $250,000 a year in “membership” fees to get full access to both halves.

But despite this uneven degree of academic rigor (or maybe because of it), my colleagues in MIT’s central fundraising office would always want to bring over donors for a quick, drive-by tour. They wanted donors to see something shiny. They wanted to see the indoor farm (now shut down after its own scandal) and its pink and blue lights. They wanted to see our cool building and take a selfie. They wanted to say they’d been there.

But when it came time for my MIT fundraising colleagues to ask these donors for philanthropic support, very rarely did the money get earmarked for the Media Lab. Usually, it went to the science and engineering departments on campus. At the time, I joined my Media Lab colleagues in a slow burn, thinking we were being used and exploited. But now I realize what some of my fundraising colleagues had probably figured out for themselves: “All icing, no cake.” That’s what they understood.

Things had been weird at the Media Lab from my first weeks there. Not unorthodox, or “anti-disciplinary,” as Ito liked to say, just plain weird. And a big part of this involved Epstein. The question of why Ito stayed connected to him wasn’t really answered very well in the MIT report. For one thing, the total of Epstein’s contributions, even including both his own gifts and the gifts he claimed to have helped arrange from others, was well under $10 million. That sounds like a lot, but is actually small change for a school that was in the midst of a $6 billion fundraising campaign.

Whatever Ito’s reasons, Epstein became a topic of constant discussion at the Lab. We really couldn’t understand why Ito was running the risk of associating with such a creep. (It turns out to have been more extensive than we knew. According to the MIT report, “In addition to his donations to the Media Lab, Epstein funded two of Ito’s personal ventures: $250,000 in a company that was formed to commercialize technology developed at MIT, and $1 million into a $9 million private investment fund that Ito manages.”) Ito knew that Epstein had been convicted of a sex crime in 2008. You could Google it; we all did. Roughly half of the Media Lab’s budget was supported by corporate sponsors, and Ito had brought in plenty of other private donors. There seemed to be lots of money to go around without taking Epstein’s donations.

But Ito also thought Epstein was a financial wizard, and he liked smart people. Ito was also a big believer in forgiveness and restorative justice. When I spoke with the MIT investigators, I told them that we had a visiting fellow at the Lab who’d murdered someone, spent years in jail, and then turned his life around. It was that kind of place.

Ito had so much faith in forgiveness and restorative justice that when everything blew up, he thought he could get the Media Lab and the outside world to forgive him as well. And it speaks well of his reputation that, for a brief moment, it sort of worked. Hundreds of people signed a petition asking him not to quit.

Ito also had detractors, however. And a key turning point came when a non-tenured faculty member named Ethan Zuckerman resigned in disgust. (It was an odd resignation, one that wouldn’t go into effect for a whole academic year. But it did garner a lot of attention. And by April 2020, the University of Massachusetts Amherst announced that Zuckerman would be starting as an associate professor of public policy, communication, and information in the fall.) Zuckerman was the one who directed Swenson to an organization called Whistleblower Aid, which in turn connected her with Farrow.

Then came Friday, September 6th, 2019, when Farrow, now the most famous journalist in America, dragon slayer, celebrity, son of Mia Farrow and Woody Allen, published the emails that Swenson had given him. My emails. There was a blurb for his forthcoming book at the bottom of the New Yorker article, with a link to Amazon where you could pre-order it. Ito resigned the next day.

While Ito was still holding on, he’d remained the focus of media scrutiny. But with Ito out and Epstein dead, I’d become the next obvious person to go after, thanks to Farrow. Which is how I ended up traveling westbound along I-70 early on the morning of September 9th, with a car full of houseplants and clothes.

Epstein, who died last summer in his jail cell, was a horrible person who sexually abused young teenage girls. He should never have been permitted to visit the MIT campus following his 2008 conviction on charges of solicitation of prostitution involving a minor. As the MIT report makes clear, his presence on the campus, and his role as a donor, had been a subject of debate among senior university officials long before I began my job, and it continued to be discussed both during and after my tenure. If, back in September 2019, Farrow had been successful in uncovering the real story of how at least three MIT vice presidents found ways to variously justify, excuse, whitewash, ignore, or limit Epstein’s involvement with the Media Lab, the New Yorker may well have scooped MIT’s own investigators. But as with Farrow’s other serious journalistic lapses—documented in recent months at the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, and here at Quillette—Farrow instead cherry-picked information from the limited sources he had and misinterpreted basic facts along the way, so as to suggest a neat but misleading narrative.

Through my role at MIT, I had several brief meetings with Epstein. At all times, I found his involvement with the Media Lab inappropriate—concerns that I communicated repeatedly to Ito and other senior colleagues, as documented in the MIT report. (The authors note that “several witnesses pointed to the then-Media Lab Director of Development”—that’s me—“as particularly disturbed by Epstein’s involvement with the Media Lab.”) And I regret that I didn’t do even more. Nevertheless, I cannot allow a grossly distorted version of events to remain unchallenged in the journalistic record.

Of the two or three times I met Epstein, one was at a 2014 TED conference in Vancouver. Epstein wasn’t allowed in the actual conference (you had to be approved to get in), and so he would sit in the lobby of the Fairmont Pacific Rim hotel, and people would come to him. Ito, who’d met Epstein the year before, had suggested that I email him to arrange a meeting. And so Epstein and I ended up having an awkward conversation of about five or ten minutes. He had two young women with him (they appeared to be adults, but young), whom I politely tried to include in the conversation. It was clear that this nicety was not required, and I quickly stopped trying. Soon, one of the Google founders walked by, and Epstein decided to speak with him instead. My time was up.

I also talked with Epstein once (or maybe twice) when he came to the Media Lab to visit with professors and researchers whom his donations (or prospective donations) supported. I didn’t attend the actual meetings, as Ito thought that development people ruined the vibe. (Some of his richest friends outwardly despised fundraisers.) However, Epstein would have to wait for Ito in our public reception area. Since the women in the office understandably didn’t want to interact with him, I volunteered to greet him and offer him coffee.

Those were my direct personal interactions with Jeffrey Epstein. Contrary to what one might have concluded from all the headlines, I wasn’t involved in any other aspect of Epstein’s existence. I did not go to his home. I did not go to his island. I never saw him with women who I thought were under 18. And for what it’s worth: The only person I’ve had sex with in the past 25 years is the man who is now my husband. So I wasn’t exactly the kind of guy Epstein arranged sleepover dates for.

But when it came to the back-office processing of Epstein’s donations to the Media Lab, yes, I was absolutely right in the thick of it. Ito was the one who would solicit donations from Epstein. (In industry parlance, we called these donations “gifts,” which made them seem a bit more glamorous.) As MIT’s four-month investigation would reveal to the public (and as insiders knew all along), MIT senior administrators had given detailed instructions to Ito in 2013 about how and when MIT would accept Epstein’s gifts. Specifically, MIT would accept these gifts “anonymously” and as quietly as possible.

As a purported smoking gun, Farrow reported on one 2014 Epstein donation as follows: “Ito wrote [to a colleague and me], ‘Make sure this gets accounted for as anonymous.’ Peter Cohen, the M.I.T. Media Lab’s Director of Development and Strategy at the time, reiterated, ‘Jeffrey money, needs to be anonymous. Thanks.’” Stripped of context, the quotation, as with Farrow’s whole article, appeared to convey the sinister machinations of a rogue cell within MIT that sought to mask its Epstein-related activities. But the reality was more boring—too boring for Farrow’s tastes, apparently.

In its public branding, the Media Lab presents itself as a sort of independent playground for “art, science, design, and technology,” where “unconstrained by traditional disciplines, Media Lab designers, engineers, artists, and scientists strive to create technologies and experiences that enable people to understand and transform their lives, communities, and environments.” In practice, the Media Lab is part of MIT proper, just like any other department or lab. So, Ito wasn’t able to accept Epstein’s money without the consent of senior MIT administrators and MIT’s central Resource Development office.

After I arrived at MIT in 2014, one of my jobs was to ensure Epstein’s gifts got processed according to the instructions that had been worked out in 2013 by Ito and three now-departed members of MIT’s “Senior Team” (as it’s called): Vice President and General Counsel R. Gregory Morgan, Vice President for Resource Development Jeffrey Newton, and Executive Vice President and Treasurer Israel Ruiz. In a statement released to the MIT community on September 12th, 2019, just six days after Farrow’s article was published, university President L. Rafael Reif indicated as much: that senior administrators at MIT had approved the Media Lab’s taking gifts from Epstein, and had instructed the Lab to mark these as anonymous. He also admitted that he himself had signed a 2012 letter thanking Epstein for his donations to an engineering professor at MIT.

While the situation at the MIT Media Lab was unusual due to Epstein’s uniquely infamous nature, I believe that development directors at thousands of universities, arts organizations and other nonprofits will recognize the highly bureaucratized nature of much of my day-to-day role. In fundraising, we talk about “front-line” work and “back-office” work. I was on the front line with many donors at MIT. But with Epstein, I was not. Nor was I the decision-maker when it came to how MIT should treat Epstein. As was made clear in the MIT report, Ito was the Media Lab rainmaker. He was the one with the outsized reputation, the one who spent time with Epstein, who introduced him to Media Lab faculty, who played on Epstein’s fascination with engineering and information technology.

If you’ve ever bought a new car, you might understand how this process works. A star salesman (Ito) will convince you to sign on the dotted line, and then smoothly hand you off to an associate (me) who gets you to fill out the actual paperwork and supply your payment details. Once the gifts to the Media Lab were confirmed (or just likely), Ito would pull a few finance staff and me into the process, so we could make sure that MIT’s central Resource Development office and Recording Secretary’s office were aware that the gifts were on their way.

On one occasion, as the Boston Globe reported, I did write a proposal to Bill Gates after Epstein told Ito that the Microsoft co-founder wanted to see one. But even this was done on instructions from Ito, and the whole exercise was conducted through the university’s officially documented channels. Sometimes, I would involve Swenson in this process, which is why she was privy to so many emails related to Epstein. As Farrow’s reporting shows, the sheer quantity of correspondence is a boon to anyone looking to cherry-pick the record. But it also shows that this was hardly a conspiratorial endeavor. Most conspirators don’t cc their colleagues about their secret plans.

One reason why it has taken me this long to write my side of this story is that, as readers may already see, it is a difficult story to tell without getting caught up in the side plots and politics of university life. That’s a subject I’ll cover in greater detail in my forthcoming book. One especially compelling backstory here is how Ito, a tech entrepreneur who never finished college and had no academic background when he arrived at MIT, became director of the Media Lab. Another is how a donor such as Epstein could become a fixture at the Lab with the knowledge of three powerful MIT vice presidents. Exploring why smart people at MIT would even consider such a thing is part of my book. (I’ll also be looking at the situation at Harvard, my other alma mater, where equally intelligent people got themselves into a similar mess.)

But the more personal story, in my case, is about how ordinary people are essentially powerless against the mass media, especially when it gets channeled through a celebrity reporter such as Ronan Farrow. In the modern social-media environment, reporting a good story often is no longer sufficient. Outlets want reporters who can hawk those stories on a variety of platforms. Farrow has a million followers on Twitter. As of June 30th, I had 31.

But even so, one would expect that, no matter how famous a reporter may be, a publication such as the New Yorker would correct clear mistakes—especially when they appear prominently, in the first paragraph of a high-profile investigative story. In his September 6th article, Farrow reported that “Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as ‘disqualified’ in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university.” Later in the story, readers were reminded of Epstein’s “disqualified status as a donor.” And what does “disqualified” mean? Farrow appears to implicitly answer this question by repeating the term, and then immediately quoting Swenson to the effect that “I knew [Epstein] was a pedophile and pointed that out.”

On that one word—disqualified—hinged Farrow’s entire conspiracist narrative. Yet it was clear that the reporter had no idea what “disqualified” meant in the context of MIT’s institutional jargon—either because he didn’t do his research, or didn’t understand the research when it was presented to him. Indeed, less than a week after Farrow’s article appeared, his own source—the aforementioned Signe Swenson—told MIT Technology Review reporter Angela Chen what everyone inside the MIT fundraising bureaucracy already knew. As Chen noted, the “disqualified donors” list “didn’t usually mean a donor’s money was off limits under MIT’s rules, but just that the person was considered unlikely to donate.”

Or in Swenson’s own words:

If there was a prospect where they reached out three times to try and cultivate them and then got no response or negative response, based on those contact reports, someone would have made them disqualified. Usually, it just indicates it would be a waste of time for a development officer to pursue this relationship.

And it gets worse. When the MIT report came out on January 10th, it showed that not only did the word “disqualified” not mean what Farrow suggested it meant in his New Yorker article, but also that Epstein had never even been categorized as “disqualified” by MIT to begin with:

Contrary to certain media reports, neither Epstein nor his foundations was ever coded as “disqualified” in MIT’s donor systems. Further, the code “disqualified” does not mean that a person or entity is “blacklisted” or prohibited from donating to the Institute. Rather, the term “disqualified” is a database code for any donor who previously donated to MIT but presently is dormant or is no longer interested in giving to MIT.

Let’s pause to summarize these events, so that readers may appreciate why my lawyers and I have repeatedly asked the New Yorker to correct the record: (1) Based on a set of emails whose context Farrow either didn’t understand or properly investigate, the reporter suggested to readers the existence of a conspiracy within the Media Lab—centered on my boss and me—that sought to secretly accept money from a “disqualified” donor, and to hide evidence of our actions from the rest of MIT by making the source “anonymous”; (2) Farrow’s own source then put forward information that showed his reporting to be undermined by ignorance of MIT institutional protocols; (3) a comprehensive MIT report conclusively demonstrated that the donations from Epstein were received in line with policies that, however misguided, had been explicitly set down by three of the university’s vice presidents; (4) contrary to Farrow’s report, Epstein had never even been classified under the “disqualified” category in the first place.

On May 17th, Ben Smith wrote a long article for the New York Times about this pattern in Farrow’s writing—evident in both his magazine stories and his 2019 book Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators. As Smith notes, Farrow’s stories often contain real and important facts, which he then expands spuriously into “narratives that are irresistibly cinematic—with unmistakable heroes and villains.” Conspiracies, in other words. While I’m not a famous person, like Farrow’s other targets, this description of his technique otherwise fits my case. Yes, Epstein was a donor to the Media Lab. (The world already knew that.) Yes, Epstein claimed to have facilitated gifts to the Media Lab from Bill Gates and financier Leon Black, as Farrow reported. (That was indeed a real scoop for Farrow, since the gifts had been anonymous. But it was hardly a scandal that either of these two prominent philanthropists had donated to MIT.) But the overall conspiracy into which Farrow shoehorned his scattered evidence simply didn’t hold water.

In his battle with Harvey Weinstein and Farrow’s own bosses at NBC, the reporter could make a claim to the status of underdog (albeit a very privileged one). Farrow’s book Catch and Kill makes it abundantly clear that he views himself in this role. But my own experience shows that Farrow is quite happy to bully others and evade accountability, and that he has surrounded himself with enablers who are willing to assist in that project.

My arrival in Illinois marked the beginning of a long period of waiting. MIT’s president said the investigation (which ended up being conducted by not one but two law firms) would take about a month. My attorneys and I decided to sit it out. I cooperated with the team from Goodwin Procter, the lead firm, speaking with them in October. I read novels at home and watered my garden during a lengthy drought in Illinois. The one-month mark came and went.

By Thanksgiving, the delay began to seem ominous. Angela Chen, the same reporter who’d written up an interview with Swenson back in September, told me she thought the investigation might continue into March. Every day that MIT didn’t put out a report was another day that Brown University, my then-employer, might decide to fire me. I also worried that the report, once it was published, might shift the blame onto rank-and-file staff, myself included, and not the actual decision-makers.

Finally, on January 9th, my attorney and I were told that the MIT report was going to be released the next day. I felt relieved and nervous at once, and I prepared a statement for the press.

I’ll be dedicating a chapter of my book to the MIT report. Suffice it to say here that it was in many ways very wide-ranging and detailed, while also suffering from the many restrictions that MIT placed on the investigators. For instance, it had little to say about what happened outside of MIT—including Epstein’s and Ito’s visits with others off campus. Nor did it provide much detail on the donations that Epstein claimed to have facilitated from Gates and Black. You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to suspect there might be things that MIT didn’t want to reveal or didn’t even want to know about.

From a personal perspective, the most disappointing thing about the report was that my name was nowhere to be found in it, even though I am referenced in several places by my title (“director of development”). This decision apparently was adopted in good faith, so as to protect me and other mid-level employees who were merely implementing the will of the university’s decision-makers. And for individuals who were being dragged into the story for the first time, this was surely a blessing. But in my case, it was the opposite: Having been castigated in the press for four months, the failure to identify me by name was disastrous. The report vindicated me, yes. But unless you search on my job title, you wouldn’t know that the scheming Peter Cohen invented by Farrow is actually the same “director of development” shown to be blandly going about his bureaucratic duties in the MIT report.

As for the lessons to be learned, it’s important to remember that MIT is hardly alone. In his effort to rehabilitate his reputation, Epstein donated money to numerous prestigious institutions—including Harvard, which published its own report on May 1st. That report suggested there were Harvard department heads and administrators, faculty members, and development officers who continued to cultivate Epstein long after his 2008 conviction prompted the university’s president to formally ban his donations. Some of them encouraged Epstein to raise money for Harvard from his associates as a way to get around the ban. Others viewed the prohibition as temporary.

Why? Because university officials, like politicians, always have fundraising on their minds. And development officers are judged by the money they bring in, not by the money that they block by raising ethical concerns. “This could have happened to any of us,” is what some development colleagues at other universities told me when my emails got published. In university fundraising, sometimes you simply take the money, cross your fingers, and hope that it doesn’t blow up in your face.

I have never met a development officer, department chair, or center head whose annual metrics don’t include gifts raised. In setting up a committee to review potentially controversial donations in the future, Harvard described the conflict of interest in a comically understated way: “Our review made clear that a faculty member’s interest in his own work; a department chair’s interest in his own department; and even the pressure development staff feel to raise money rather than reject it all have the capacity to influence judgments in ways that could be detrimental to Harvard’s interests as an institution.” To which I said to myself: “You think?”

Nowhere in the MIT report does it suggest that the trio of MIT vice presidents responsible for the Epstein policy was acting on ulterior motives. They simply wanted to find ways to help the Media Lab director raise funds, not stand in the way of him doing so. Even though they weren’t development officers, the vice presidents and Ito all felt that raising money was an implicit part of their job description.

The same was plainly true at Harvard, where at least some professors and school officials were incentivized to ignore their president’s prohibition on cultivating Epstein because they were under such enormous pressure to secure donations. Internal and external investigations, gift-review boards, mea culpas, and public handwringing won’t eliminate these incentives. Nor, I predict, will Harvard’s recently released (and first ever) gift-policy guide, which is conspicuously vague. There will certainly be other donors with dubious reputations at both universities in the future, and I’m not sure if any of the guidelines that Harvard or MIT have established will be enough to prevent another scandal. Epstein wasn’t the first, and he won’t be the last.

In December, during my agonizing wait for the MIT report to be published, I decided it was time to formally ask the New Yorker to correct its reporting. Over the course of the next four weeks, my lawyer and I sent polite notes to New Yorker general counsel Fabio Bertoni; Farrow’s fact checker, Sean Lavery; and Farrow himself. Unfortunately, what we hoped would be a relatively straightforward process proved fruitless. Even following the publication of the MIT report on January 10th, the magazine has refused to act. Farrow’s story remains freely available on the New Yorker’s web site, and other reporters continue to link to it. In speaking with my lawyer and me, the New Yorker has acted as though the story is set in stone. But when Ito resigned on September 7th, it was happy to add an update to the top of the story. It was unfair and maddening.

Will the New Yorker ever correct the record? It’s possible. But based on my reading of my correspondence with the magazine, this will happen only on the condition that I act as a source for a future story about the Media Lab and its donors, something I refuse to do. Consider these remarkably similar responses to my lawyer and me from Farrow, Lavery, and Bertoni:

- From Farrow, January 11th, 2020: “The New Yorker does not intend to update our story from September.… That said, if you have more information regarding MIT’s donation practices and policies and its relationship with Jeffrey Epstein and can demonstrate the ways in which the administration was involved (I’m sure you saw their report suggesting they were not), we are happy to interview you and review any evidence you can provide. We would consider a follow-up story if the information is substantially newsworthy.”

- From Lavery, January 15th, 2020: “We’d be happy to speak with you regarding anything else you may know. I’m particularly interested in what Richard MacMillan [an MIT development colleague] meant when he told you the university wasn’t accepting Epstein’s gifts and asked you what happened to the Leon Black route. Let me know if you can expand on that exchange for us.”

- From Bertoni to my attorney, December 20th, 2019: “The New Yorker stands by the piece as published, and does not believe that any correction is appropriate or required.…Nevertheless, if Mr. Cohen would be interested in speaking with Mr. Farrow on the record, Mr. Farrow is happy to reach out to him in the next weeks to see if there may be a follow-up story that would be of interest to our readers.”

I’m sure all three of these men (each of whom was offered an opportunity to provide comment for this article) would be scandalized by the suggestion that they’d implied they might balance the record only if I first agreed to dish dirt on others. But the meaning of their words seems quite plain to me. Lavery’s words, in particular. (The “Leon Black route” to which he referred had already been reported on by Axios, which, like the New Yorker, had been given leaked emails by Whistleblower Aid in September.) But I wasn’t going to take the bait. In rejecting Lavery’s request to provide new information, I wrote: “Due to confidentiality agreements and the ethics of my profession, I am unable to comment on the activity of donors. Thank you for understanding.” To which he responded: “I understand your position re: ethics in your profession, but would simply point out that everyone else has spoken on this, and we could potentially speak in a confidential manner if you have material or knowledge that would further clarify things.”

In all of these email conversations, the New Yorker saw fit to emphasize that I declined its request for comment before Farrow’s article appeared. That’s true. Development people almost never talk to the press, and we don’t reveal confidential information about donors. If we did, our careers would be over. Yet now, after printing verifiably incorrect information about the Media Lab and me, the magazine has repeatedly instructed me to revisit my decision to abide by my professional obligations, or else—as I interpret their words—they’ll refuse to act. And even if I do provide “newsworthy” information, the magazine can publish it or not at its discretion, repackaging its correction as a new exposé if they do. This strikes me not just as bad journalism, but dubious business practice.

More shocking still, it’s not clear that Farrow has even read the MIT report; or, if he has, that he understands the contents. In his note to me, quoted above, Farrow asked me for “information regarding MIT’s donation practices and policies and its relationship with Jeffrey Epstein…demonstrat[ing] the ways in which the administration was involved (I’m sure you saw their report suggesting they were not).” But of course, “their report” very clearly indicates that the “administration” was involved, right up to the vice-presidential level. (It was also unclear to me why Lavery took over the conversation and began negotiating with me directly. Wasn’t he the fact checker?)

15/ We take corrections seriously and would be happy to correct something if it were shown to be wrong. But Ben has not done that here.

— Michael Luo (@michaelluo) May 18, 2020

In June, I made one last attempt at a correction. Following Ben Smith’s New York Times piece on Farrow’s journalistic lapses, newyorker.com editor Michael Luo wrote a 16-part Twitter thread in which he attempted to defend Farrow. That includes number 15, which said: “We take corrections seriously and would be happy to correct something if it were shown to be wrong.” So I emailed Luo on June 9th; explained the problems with the September 6th story; attached all my previous emails from Farrow, Lavery, and Bertoni; and asked him to make a correction. To which I got the now-usual reply, ending with: “We stand by our story. Thank you again for reaching out to us.” So much for “We take corrections seriously.” (Luo, too, was offered an opportunity to provide comment for this article. Like his three colleagues, he didn’t respond.)

The New Yorker story remains an albatross around my neck. It won’t go away, and I can’t get it corrected. Anyone who Googles my name will end up reading it. Even the New York Times, America’s paper of record, fell into the trap of relying on it. On January 10th, I sat at a restaurant in Bloomington, Illinois, reading the press coverage surrounding the release of the MIT report, and texting a Times reporter, asking her, in vain, to please mention my objections to the Farrow story in her just-published article. My request seemed justified, given that the Times story quoted one of my emails (anonymously), and linked back to the New Yorker. She said she would check with her editor, but the Times declined to make the change. It exemplified the willingness of dozens of reporters to parrot what Farrow had written on September 6th. (I finally did hear back from this Times reporter 12 days later—when I resigned from Brown and she wanted a comment.)

So what did I learn from all of this? I’m still trying to figure that out. And I hope that by conducting research and interviews for my book, I’ll find better answers to my questions than those contained in the MIT report. Along the way, however, a few folks have offered me some pithy words of wisdom, and I’ll share a couple of them here. When I was feeling especially down, I’d reach out to a couple whom I’d become friendly with in Houston, where I lived on and off for 12 years. They would encourage me to move back, noting slyly that Houstonians were more accepting than Yankees of past misdeeds. “It’s hard to fall when you’re already on the floor,” they’d say, in reference to Houston’s forgiving culture.

In January, when the MIT investigation wrapped up, I told them I was happy to have been vindicated. They agreed that this was an encouraging development, but the wife doubted it would change the minds of reporters who’d already moved on to their next project. “This is not a world where justice prevails,” she wrote, popping a pin in my celebratory bubble.

At first, I thought she was being much too dramatic. But in a way, she was right. And what I came to realize is that, if I was going to have my story told, I would have to tell it myself.

An interview with the author.