Culture Wars

Arguing in America

Lawyers like to joke that a ruling is probably correct if both sides are equally upset by it.

Jacob Siegel’s recent essay for Tablet entitled “The New Truth” manages to capture something important about the current state of discourse in America. Essentially, the marketplace of ideas is beholden to a despotic elite, and is being used to proselytize a new moral order. This moral order is perpetually in flux and is subject to ongoing revisions from its adherents. The only constant is that current systems of morality have failed and are, in fact, perpetuating immorality.

The important question of how we got here has yet to receive a satisfactory answer. Yes, clear and early warning signs about the growth of this new culture on campuses were missed or dismissed. Yes, the hard sciences are becoming increasingly politicized and pressured to accept that “other ways of knowing” are at least as valuable as the scientific method. But none of the existing answers properly explains how the national discourse has surrendered to the ascendant dogma of what Seigel’s Tablet colleague Wesley Yang has called the successor ideology.

The successor ideology is what happens when ideas meant to encourage critical self-reflection become a part of an echo chamber and grow increasingly divorced from reality.

— Wesley Yang (@wesyang) May 21, 2019

The list takes on the coloration of every romantic, reactionary, and left-wing shibboleth ever created.

What has been missing from this discussion is an acknowledgement that Americans are not engaged in truth-seeking conversations about complicated issues. Instead, they are litigating them. Law students are taught that what is legal and what is moral are different questions. A society’s laws may be a rough approximation of what that society deems moral, but these two considerations often diverge in practice, whether in law or in everyday life. It is certainly immoral to cheat on your spouse, but it isn’t illegal. Exceeding the speed limit is illegal, but there is nothing necessarily immoral about it. During the Holocaust, families that took in and sheltered Jews were breaking the law, while the soldiers and citizens reporting and executing them were following it.

This distinction is frequently (and understandably) lost on the general public. We expect the laws we follow to align with our general moral compass. As a result, we are shocked when legal outcomes do not align with moral ones—the O.J. Simpson verdict may have been legally valid but it was also morally scandalous. Nevertheless, understanding the distinction between morality and legality can help us understand why lawyers act the way they do—they are trained to operate in a world where—aside from legal ethics and professional obligations—the only rules that apply are legal ones.

A lawyer is not hired to find the truth or the morality of a case, but to advocate on behalf of his client. To do that, he will use every argument and legal tool available. In fact, he has an ethical obligation to do so. The American Bar Association explicitly requires a lawyer to “zealously assert the client’s position under the adversarial system.” When a lawyer enters the courtroom, the objective is to win, not to determine truth or morality. Where truth and, in rarer cases, morality are determined, they are by-products of the adversarial system. Defence lawyers frequently advise their clients not to take the stand in criminal cases, even though doing so would surely improve the truth-finding ability of the court. But the objective is acquittal, and if a client’s testimony is likely to jeopardize that goal, he will be advised not to testify under oath.

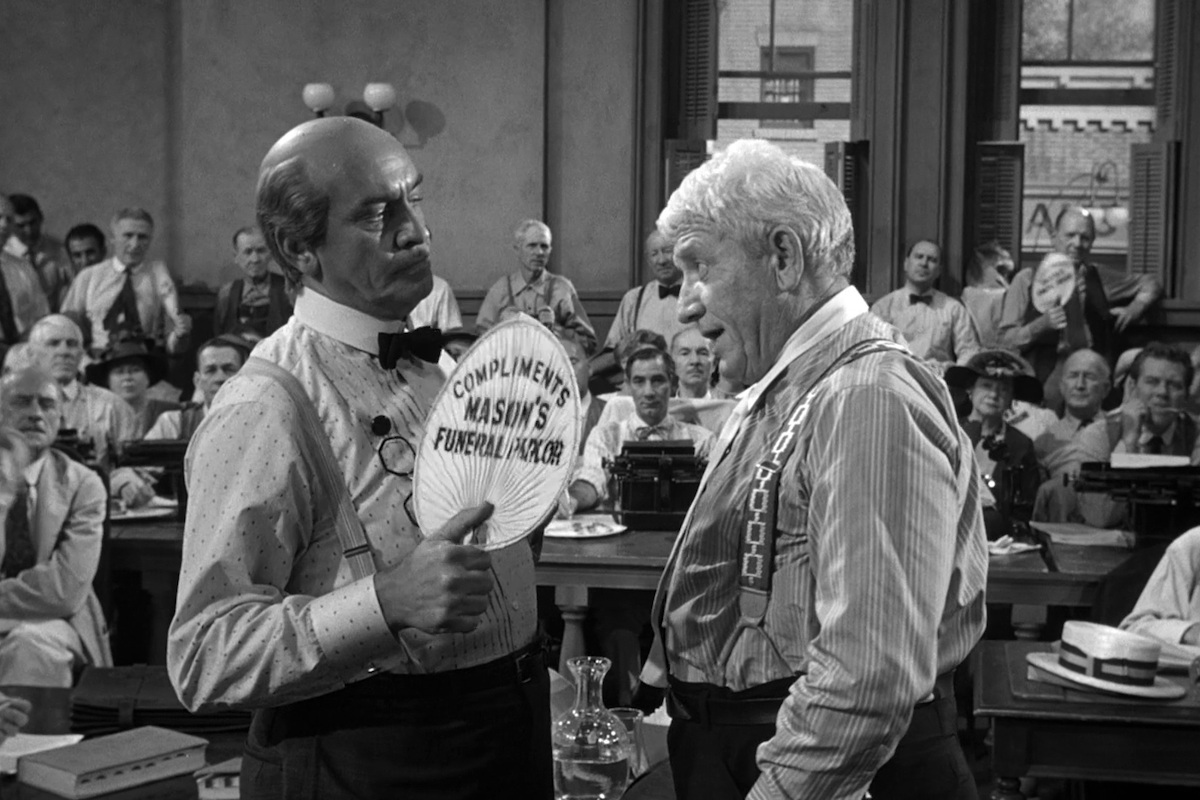

This approach can lead a lawyer to take uncompromising positions that fly in the face of reasonableness and common sense. He might attack the credibility of a physician whose findings do not help his client, or he may attack a witness’s credibility to undermine the reliability of unhelpful testimony. If it is expedient, a lawyer may even defend two opposing propositions at once or disguise an extreme claim as a perfectly reasonable—and indeed the only moral—one. Most importantly, in the adversarial system, a lawyer rarely concedes an argument to the opposition. When filing a civil defence, it is common to simply assert that, “The defendant denies all statements made by the plaintiff except for those expressly admitted herein.” Why agree to uncontroversial timelines, correspondence, facts, and definitions if you can force your opponent to do that work and possibly make a mistake or omission in the process. This tactic can sometimes produce absurd results:

Nevertheless, the court system generally works (despite the occasional absurdity) because the process is overseen by a judge who understands the rules of the game and who decides what is material to the outcome of the case and what is smoke and mirrors. His job is to call balls and strikes in the courtroom, ruling which arguments are in and out of bounds. Lawyers like to joke that a ruling is probably correct if both sides are equally upset by it.

Truth-seeking discussions, on the other hand, do not operate in a litigious manner. We don’t want our morals, governmental policies, science, and understanding of society to be a matter of who is the better litigator. The liberal tradition is intended to allow truth to emerge from exploration and good-faith criticism that earnestly seeks an accurate representation of reality and not the promulgation of a particular position. Our survival and success as a species relied on uncovering the workings of the world so that we could navigate it with greater knowledge and confidence. We must take the universe as it is; we cannot will a preferred alternative into existence.

The current state of discourse, however, resembles a litigious battle where the only goal is victory. No quarter is given and no concession is made, since to do so would move the dialectic towards the kind of discussion in which ideas are presented, explored, and accepted or rejected based on their evidentiary support. The arguments taking place on online platforms and across the media and parts of academia are ruthless pitched battles in which facts only matter to a participant if they support his position. If a combatant has a personal flaw or an embarrassing tweet in their archive, expose it and humiliate them until they retreat. If they are not the correct race, gender, or class to speak on a topic, insist that their opinion be excluded from consideration. This is litigation 101: Discount or disqualify those who oppose you, regardless of the merits of the evidence or arguments they possess.

But outside the legal system, there is no authority to right the ship and call out foul play. There are no rules and no consequences for playing dirty. Lying, slandering, doxing, deplatforming are all justifiable tools in the Internet litigator’s toolbox. The only consequences are for the losers, whose careers and personal lives are too often thoughtlessly sacrificed in pursuit of victory. And the grim spectacle of reputations and livelihoods being torn to pieces online offers an effective deterrent to anyone else thinking of entering the fray. This is why many of those who might still defend liberalism prefer instead to remain silent.

This state of affairs is especially sad because understanding the complexities of issues like race, policing, drug reform, gender rights and relations, accessibility, and representation remains important. Polls indicate that the general public is more alive to the issue of race in America than ever before—I hope the opportunity this presents is not squandered by the sanctimony of those who now hold the reins of cultural power. Before joining the battle, Americans of all political persuasions should ask themselves: “Am I entering this conversation to get closer to truth, or am I only here to destroy the opposition?”