Books

The Libertarian History of Science Fiction

The connection between SF and liberty is not simply an accidental byproduct of the colorful history of SF publishing, but a necessary one tied to certain fundamentals of the genre.

When mainstream authors like Eric Flint complain that the science fiction establishment, and its gatekeeper the Hugo Awards, has “drift[ed] away from the opinions and tastes of… mass audience[s],” prioritizing progressive messaging over plot development, the response from the Left is uniform: Science fiction is by its very nature progressive. It’s baked into the cake, they say. This is a superficially plausible claim. With its focus on the future, its embrace of the unfamiliar and other-worldly, and its openness to alternative ways of living, it is hard to see how the genre could be anything but progressive. In fact, studies indicate that interest in SF books and movies is strongly correlated with a Big Five personality trait called openness to experience, which psychologists say is highly predictive of liberal values.

But openness to experience also correlates with libertarianism and libertarian themes and ideas have exercised far greater influence than progressivism over SF since the genre’s inception. From conservatarian voices like Robert Heinlein, Larry Niven, Vernor Vinge, Poul Anderson, and F. Paul Wilson to those of a more flexible classical liberal bent like Ray Bradbury, David Brin, Charles Stross, Ken McLeod, and Terry Pratchett, libertarian-leaning authors have had an outsized, lasting influence on the field. So much so that The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has deemed “Libertarian SF” its own stand alone “branch,” admitting that “many of libertarianism’s most influential texts have been by SF writers.”

So, is the connection between SF and the liberty movement necessary or contingent? While most science fiction novels are not libertarian, “[a]ll the best known libertarian novels,” says Jeff Riggenbach, “are science fiction novels,” from Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged to Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon. Even among conservatives, Stephenson himself writes, it is the “ostracized libertarian wing,” the wing “still able to hold up one end of a Socratic dialogue,” that has “disproportionately high representation among fans of speculative fiction.” Libertarians even have their own SF literature awards. Each year, the Prometheus and Prometheus Hall of Fame awards are given out by the Libertarian Futurist Society, a tradition dating back to the late 1970s. Instead of a trophy, winners are given a one-ounce gold coin “representing free trade and free minds.”

There’s also a prominent publishing house, Baen Books, that prioritizes liberty-themed SF literature. Though its authors and editors are ideologically diverse, ranging, says author Larry Correia, “from libertarian to communist,” Baen nevertheless represents an impressive cohort of staunch liberty defenders, among them Correia himself, Sarah Hoyt, and Michael Z. Williamson. Although Baen has attempted to distance itself from political affiliation, the company frequently publishes liberty-themed tracts and anthologies, including the recent Taxpayers’ Tea Party: A Manual For Reclaiming Our Country, by Sharon Cooper and Chuck Asay.

Science fiction’s libertarian roots

Although some critics trace SF’s roots all the way back to Homer’s Odyssey, Plato’s Republic, or, as Nabokov once argued, Shakespeare’s The Tempest, most scholars agree that the genre as we know it began with the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which many libertarians understand to be a cautionary tale about what happens when power-seeking men, under the guise of progress, devise a promethean monster (the State) that takes on an uncontrollable life of its own. Whether Shelley—whose parents were the libertarian feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the “father of modern anarchism” William Godwin—intended this reading or not is unknown. Nevertheless, Mikayla Novak argues that the story remains a libertarian favorite for “the ways in which Mary Shelley grapples with matters of individuality, free will, and moral choices, and the place of individuals situated within broader civil society.”

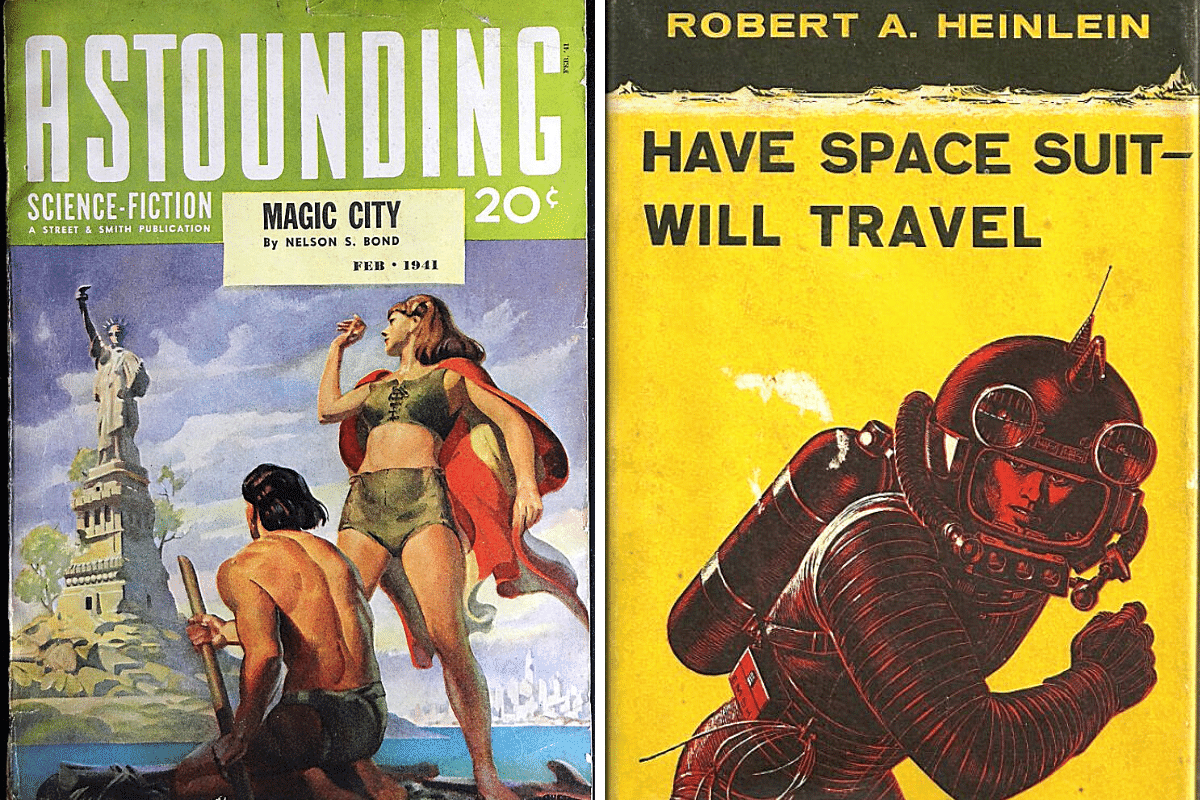

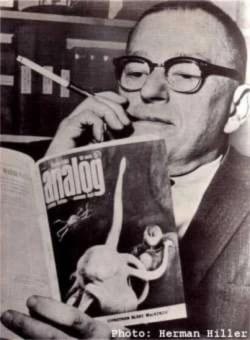

Still, it is difficult to have science fiction in the modern sense until you have science in the modern sense. While the works of Shelley, Jules Verne, and H.G. Wells were successful examples of proto-SF, it was the rise of the pulps in the 1930s that finally made it possible to make a living writing consistently in the genre. Magazine SF, with its swoopy chrome ships and bubble-suited space men, grew initially out of publications like Amazing Stories, founded by Hugo Gernsback (of the eponymous Hugo Awards) in 1926. But it wasn’t until 1938, when John W. Campbell took editorial control over Astounding magazine, that the field began to properly develop its libertarian strain, a consequence of what SF historians call the “Campbellian Revolution.” Today, Campbell is still considered “the most powerful editor in the history of SF,” says Professor Michael Drout of Wheaton College. With a strident editorial hand, he ushered in the “Golden Age” of SF and shaped the work of greats like Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Lester del Rey, among many others.

Campbell’s ideas sometimes veered into Nietzschean superman territory and he was often taken in by pseudo-scientific humbug like extrasensory perception and telepathy (a weakness exacerbated by his friendship with L. Ron Hubbard). But he was, all things considered, a cheerleader for freedom and the American way. With Campbell at the helm, a new ethos came to define the industry—a “tradition,” writes Eric S. Raymond, “of ornery and insistent individualism, veneration of the competent man, an instinctive distrust of coercive social engineering, and a rock-ribbed empiricism that valued knowing how things work.” In short, the new hard-SF emphasized a spirit of self-reliance and libertarian preparedness that saw heroic individuals, rather than government, as the key to solving humanity’s future problems.

The attitude of rugged American individualism that defined the pulps grew, in part, out of a sense of loss. By the 1930s, the last frontiers of Earth had been explored or mapped, creating a yearning for new vistas. As history closed off the real frontiers, SF created new ones. The spirit of the pulps can also be seen as a reaction against the rising tide of collectivism. Communism and fascism were sweeping through Europe and FDR’s New Deal policies were increasing the size and scope of government at home. An “intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol,” as Reagan would later put it, was promising to cure the ails of Americans and plan their lives for them.

It made sense, then, that many of the period’s big names were problem-solvers with backgrounds in science or engineering, including Campbell, who held a bachelor’s in physics from Duke, along with his protégé Robert A. Heinlein, an aeronautical engineer who would become one of the genre’s greatest talents.

Heinlein and the competent man

I have learned this about engineers. When something must be done,

engineers can find a way… turn your engineers loose.

Robert A. Heinlein, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

Campbell’s preference for realistic, logically rigorous storytelling allowed him to “turn his engineer loose.” Under Campbell’s editorship, Heinlein and other writers introduced the reading public to a new type of protagonist, “the competent man”—a rugged, technically skilled, polymathic figure who was just as comfortable fixing his spaceship as he was defending himself with a ray-gun. In a postwar age of atomic uncertainty and space exploration, jack-of-all-trades survivalists made for excellent heroes. In his novel Time Enough for Love, Heinlein describes “the competent man” as follows:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyse a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

The culture that Campbell and other Golden Age authors created was one of techno-optimism and a confidence that reason and human ingenuity would save the day. One of “science fiction’s central assumptions,” writes Alec Nevala-Lee in Astounding, was “that the skills that it developed in its writers and readers would prepare them for an unknown future.” SF’s faith that rational individuals can solve their own problems and plan their own lives, its belief that science and innovation can liberate humanity from the slings and arrows of an unnecessary status quo—these are qualities that set the genre at odds with both progressive and conservative ideologies. They are also the qualities that have enthralled many libertarian fans.

Thanks to writers like Heinlein, SF has produced its share of converts, too. According to Jeff Riggenbach, in a survey conducted by the Society for Individual Liberty in the 1970s, “one libertarian activist in six had been led to libertarianism by reading the novels and short stories of Robert A. Heinlein.” Dave Nolan, a founder of the Libertarian Party, was one such activist. Nolan was so influenced by Heinlein, says Brian Doherty in Radicals for Capitalism, that he wore a “Heinlein for President” button during the 1960 campaign.

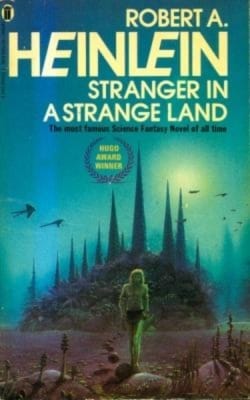

Although he began his career as a utopian socialist working for Upton Sinclair’s 1934 gubernatorial campaign, Heinlein underwent a political transformation and became known for the rest of his career as a libertarian “guru” of sorts. Scott Timberg at the LA Times describes him as a “nudist with a military-hardware fetish” who “dominated the pulps… and became the first science fictionist to land on the New York Times bestseller list.” A four-time Hugo Award winner, Heinlein is credited with helping to elevate SF from its ray-blaster and tentacled space-monster phase to a more serious, respectable prominence, penning such classics as Stranger in a Strange Land and, Milton Friedman’s favorite, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, a book that reads like an anarcho-capitalist blueprint for revolutionary uprising. Friedman even named his 1975 public policy book after the novel’s slogan TANSTAAFL (“There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch”).

There have been attempts to downplay Heinlein’s commitment to liberty and to label him a fascist, a spurious mischaracterization of his worldview that arose after the publication of his 1959 novel, Starship Troopers, a story set in a quasi-fascistic society. But Heinlein loathed authoritarianism and resented such accusations. “[T]o call Heinlein a fascist,” argues Adam Roberts in The History of Science Fiction, “quite misrepresents his particular brand of ideological reaction. Whilst always a patriotic American, Heinlein was ideologically invested neither in racial nor geographical ideals… his books preach a libertarian gospel.” Heinlein said as much in a letter describing his outlook, writing, “As for libertarian, I’ve been one all my life, a radical one. You might use the term ‘philosophical anarchist’ or ‘autarchist’ about me, but ‘libertarian’ is easier to define and fits well enough.”

The New Wave

By the 1960s, a group of brash young writers emerged, loosely associated with Michael Moorecock’s magazine New Worlds. This group included J.G. Ballard, Samuel Delany, Brian Aldiss, and Joanna Russ, and they began to “call foul on the old guard of science fiction.” Armed with an avant-garde sensibility, the radical New Wave, inspired by the Frankfurt School and critical theory, challenged the dogmas of the Golden Age and changed the face of SF forever. At least, that’s the story critical histories of the genre now tell.

But this is a crude revisionist narrative, born of the impulse to neatly periodize literary history. The truth is less schismatic. In retrospect, says critic Damien Broderick, it is more accurate to describe the intellectual fecundity of the New Wave (a moniker borrowed from French cinema) as “a reaction against genre exhaustion.” More than anything, the movement can be seen as a bid on the part of talents like Ursula Le Guin and Thomas M. Disch to bring a much-needed thoughtfulness and literary credibility to the field. There was also an attempt to turn the genre inward, to explore “inner space”—consciousness, psychological states, and perception—rather than “outer space.”

While some New Wave writers were political leftists who wished to dismantle the genre’s Campbellian trappings, for the most part, SF’s “School of Resentment,” to use the Bloomian pejorative, was a sequestered, insular phenomenon. Instead, the proliferation of fresh voices and renewed focus on stylistic experimentation worked to lift all boats. Like Dadaism and Surrealism, the New Wave had more to do with liberation from bourgeois artistic constraints than any political agenda. The New Wave, says Adam Roberts, “called for a more passionate, subtle, ironic, and original form of SF,” but the result was that it wound up “bring[ing] together the literary sensibilities associated with High Modernism and the energies of popular pulp SF.”

The upshot was a new type of SF, entertaining and rigorous but at the same time thoughtful and stylistically sophisticated. It was the progeny of this union—in works like Stanisław Lem’s Solaris (1961), Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965), Philip K. Dick’s Ubik (1969), Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero (1970), and Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974)—that would define SF of the 1960s and ’70s and go on to become enduring classics.

The heady, rebellious atmosphere of this period produced some of the best libertarian SF ever written: In Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron” (1961), one man fights back against a dystopian regime that enforces rigid equality of outcome through “handicaps” that stifle excellence. In Eric Frank Russell’s The Great Explosion (1962), militarists from Earth visit an isolated colony and meet a peaceful libertarian society whose people call themselves “Gands” (after Gandhi). In Poul Anderson’s No Truce with Kings (1963), aliens come to a post-apocalyptic Earth to “help” the backwards natives resolve their feuds, but the mission goes awry.

In Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966), a lunar colony rebels against Earth’s oppressive control in a struggle for independence mirroring the American Revolution. In Jack Vance’s Emphyrio (1969), the people of Halma, inspired by a legendary hero, lead a revolt against the planet’s overlords who have outlawed free trade. In Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day (1970), every aspect of life is planned by a world government run by a central computer called “Uni”—that is, until a group rises up. In Shea and Wilson’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy (1975), readers meet libertarian characters as they are drawn into a surreal, hallucinatory web of conspiracy theories related to the global Illuminati and its control of world governments. Other favorites from the era include Niven and Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer (1977) and F. Paul Wilson’s Wheels Within Wheels (1978).

Golden age redux

By the early 1980s, writers like Kingsley Amis were declaring the New Wave “officially over” and celebrating a Golden Age revival. It is more accurate to say, though, as Adam Roberts does, that “the Golden Age never went away.” Campbellian-era writers like Heinlein, Clarke, and Asimov—“the big three,” as they became known—captured numerous Hugo and Nebula awards throughout the 1960s and ’70s, and their works flew off bookstore shelves well into the 1980s and ’90s. Alongside these pulp-era pros, a generation of worthy inheritors was assuming the mantle. It was this new talent, together with the success of the Star Wars franchise, that would create a new thirst for hard-SF adventure stories and a boom in commercial SF publishing.

But the Campbellian renaissance was different this time around. A more overt, principled libertarian strain was emerging in prolific writers like Vernor Vinge, Larry Niven, Gregory Benford (longtime contributing editor for Reason magazine), Victor Milán, F. Paul Wilson, and L. Neil Smith. The works of Ayn Rand, which frequently drifted into the realm of SF and inspired a “wave toward deregulation” in the 1980s, had never been more popular. The Libertarian Party had grown rapidly since its founding in 1971 and had achieved ballot access in all 50 states by 1980. The economists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman had recently won Nobel prizes. The liberty movement was thriving.

That the SF of this period often advanced a conservative view of liberty had to do with the political zeitgeist of the time, the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan’s Big Defense, Limited Government ethos in the US and Margaret Thatcher’s free market conservatism in the UK. It was, however, Reagan’s reputation as a Cold Warrior and his enthusiasm for the Strategic Defense Initiative (“Star Wars,” as critics mockingly called it) that captured the imaginations of right-leaning libertarian authors. The idea behind SDI, to install a network of orbiting battle-stations that could serve as a nuclear deterrent and shoot down intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) using lasers, was like something out of a space opera novel.

“[A] huge fan of The Day the Earth Stood Still and its anti-nuclear war rhetoric,” writes Kevin Bankston, Reagan “grew up devouring fantastic sci-fi tales like Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter of Mars stories.” It was not surprising, then, that Reagan’s Citizen Advisory Council on National Space Policy was made up of some of the greatest SF talent of the 20th century. In addition to astronauts, scientists, engineers, and Reagan’s adviser Lt. General Daniel O. Graham, the council included authors Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, Jim Baen (of Baen Books), Robert Heinlein, and Poul Anderson. According to Pournelle, Reagan’s 1983 speech announcing SDI to the public was based on the technical plans, arguments, and phrases the council had drawn up for the president.

The free-market energy of the 1980s and collapse of the Soviet Union in the ’90s reinstated a shared consensus regarding the value of freedom and limited government. Yet it would be a mistake to see libertarian SF as an intellectual monoculture. Then and now, the sub-genre has been a spectrum. “At one extreme,” writes Eric S. Raymond, you have fiction such as “that of L. Neil Smith,” which reads like “radical libertarian propaganda. At the other extreme,” you have “what could fairly be described as conservative/militarist power fantasies… in the writing of Jerry Pournelle and David Drake.” The finest work, like that of Heinlein, tends to fall somewhere in the wide, heterodox middle.

The necessary connection

It is 2020, and though socialism is again in vogue—44 percent of millennials say they would prefer to live in a socialist country—libertarian SF is showing no signs of waning. The connection between SF and liberty is not simply an accidental byproduct of the colorful history of SF publishing, but a necessary one tied to certain fundamentals of the genre. The soil of speculative fiction, in other words, has the right nutrients for the flourishing of libertarian values. But what are they? Unlike most ideologies that advocate forms of protectionism and luddite restrictionism, the libertarian outlook values choice, freedom, and market solutions. Libertarians, writes Ilya Somin for the Prometheus Newsletter, “are more likely to welcome such technological advances as genetic engineering, cloning, and nuclear power… the genre as a whole also tends towards technological optimism.”

Another element, certainly, is a general openness to radical new ideas and an instinctive rejection of stale convention and custom. This trait unites libertarians and progressives against Burkean conservatives. Openness to novelty and diversity enables SF writers to speculate (hence the name “speculative fiction”) and go where other writers, bound by earthly limitations, cannot. SF, writes Pittsburgh University professor Elisa Beshero-Bondar, “is the genre that considers what strange new beings we might become, what mechanical forms we might invent for our bodies, what networks and systems might nourish or tap our life energies, and what machine shells might contain our souls.”

At the same time, SF stands firm against the collectivist notions of both progressives and “common good” conservatives. “The individual is foolish,” wrote Edmund Burke, “but the species is wise.” In SF, the inverse is true. The species or collective is often coercive, irrational, and destructive. In The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, Heinlein offers us a warning about left and right collectivism delivered by the character of Professor de la Paz, a “rational anarchist” who urges: “Distrust the obvious, suspect the traditional, for in the past mankind has not done well when saddling itself with governments… do not let the past be a straitjacket!”

Perhaps this is why so much of SF expresses itself as dystopian fiction, a genre which, by its very nature, cannot but take on a libertarian flavor. Totalitarianism, war, and wide-scale oppression is almost always carried out by state force. Liberation, accordingly, must come in the form of negative rights—that is, “freedom from”—and voluntarism: “[I]n writing your constitution,” Professor de la Paz instructs, “let me invite attention to the wonderful virtues of the negative! Accentuate the negative! Let your document be studded with things the government is forever forbidden to do.”

There are some exceptions. In cyberpunk novels, like Stephenson’s Snow Crash or M.T. Anderson’s Feed, dystopian misery is often a result of corporate control or not enough government. But even these works make libertarian arguments. In the case of Snow Crash, the minimal state fails to carry out its only moral duty from a Lockean perspective—to protect citizens’ natural rights. In Feed, corporations run every aspect of life, thanks to cronyism, corruption, and regulatory capture, all libertarian bugaboos.

Which brings us to a final reason that libertarian authors choose to express their ideas through a science fictional lens. While dystopias satirize and allegorize the flawed political systems and social practices that govern the world we know, SF is more often about exploring new worlds and systems. Contrary to “traditional literary fiction, which is mostly set in the present-day world or in the historical past,” writes Somin, “science fiction… makes it easier for authors to explore ideologies [like libertarianism] that differ radically from those dominant in the real world”—ideologies that, unlike socialism, have truly never been tried.