Australia

Captain Cook and the Colonial Paradox

Cook is best understood as a quintessential figure of the European Enlightenment, with all the consequences flowing from that, positive and negative.

On April 29th, 1770, a longboat from the Royal Navy bark Endeavour grounded on Silver Beach at Botany Bay in what is now Sydney’s southern suburbs. Isaac Smith, a young midshipman, leapt out and became the first European to set foot on Australia’s east coast. Four men followed—Swedish scientist Daniel Solander, English Botanist Joseph Banks, Tahitian navigator Tupaia, and the commander of the expedition, Lieutenant James Cook.

They had rowed towards an encampment of the Gweagal Aboriginal people in the hope of speaking to the inhabitants. However, all the people had fled, save for two men, who seemed determined to oppose Cook’s landing. Cook tried to speak to them, but to no avail—neither he nor Tupaia could understand the language they called back in. Cook tried throwing some nails and beads onto the shore as a peace offering, but they didn’t understand the gesture, and according to Cook, made as if they were going to attack. He fired a musket between them, and one responded by throwing a rock. He fired a second shot, wounding one of the men in the leg, and they threw two spears in retaliation. He fired a third shot, and both men made off into the bush. The British explored the huts, found some children, left gifts of beads, and then returned to their ship. So ended the first encounter between the British Empire and the indigenous people of eastern Australia, as Cook recorded it in his journal.

Exactly 250 years later, on April 29th, 2020, Dr Annaliese van Diemen, Victoria’s Deputy Chief Health Officer for communicable diseases, ignited a social media firestorm when she posted this tweet:

Sudden arrival of an invader from another land, decimating populations, creating terror. Forces the population to make enormous sacrifices & completely change how they live in order to survive. COVID19 or Cook 1770?

— Dr Annaliese van Diemen (@annaliesevd) April 29, 2020

Van Diemen was naturally criticised for making her statement in the middle of the biggest public health crisis in the state’s history. “What’s with the culture wars crap from a state health bureaucrat at a time like this?” tweeted Victorian opposition MP Tim Smith in response. “Comparing the extraordinary first voyage of Captain Cook where he charted the East Coast of Australia for the first time to a deadly virus is disgraceful.” Van Diemen’s defenders pointed out that she is entitled to use her personal social media accounts to express her personal views, that her analogy was perfectly valid, and that, since the Australian federal government had built a $48.7 million fund to commemorate the anniversary of Cook’s arrival, it was a fair matter for public comment.

A place for Cook

What are we going to do with Captain Cook? In the past, Cook was an entirely heroic figure, and the British colonisation of Australia which his exploration facilitated was an unambiguous cause for celebration. The (now unsung) first verse of the Australian national anthem begins “When gallant Cook from Albion sailed…” My 1913 Sutherland’s History of Australia and New Zealand begins with Cook’s portrait. Generations of schoolchildren have learned that he “discovered Australia.” In 1934, his parents’ cottage was dismantled brick-by-brick, shipped to Australia, and re-assembled in Melbourne. My grandfather’s old history textbook from school, H. E. Marshall’s Our Empire Story, indelicately describes Cook’s voyage as the critical first step in turning a land peopled only by “black savages” into a great commonwealth under the Union Jack. No empire in history, Marshall reminded her young readers, not even those of Alexander and Caesar, had ever succeeded in uniting an entire continent under one flag as we had done in Australia. In 1970, to commemorate the bicentenary, the Sun Herald ran a junior poetry competition and published the winner, which read in part:

The discovery of Australia by Cook and his band,

Was the wonderful beginning of the founding of our land.

From that sturdy ship Endeavour, those brave men came ashore.

They found the natives friendly, in spite of the spears they bore.

Today, Australians no longer think of themselves as British, as painting the world map red no longer has the patriotic appeal it once did. And we recognise indigenous Australians as our fellow citizens rather than “black savages” needing the protection of the British Government. The claim that Cook “discovered Australia” (which he himself never made) is recognised as untrue. He was obviously not the first person to reach Australia, as there were people there when he arrived. Nor was he the first European—that was Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon, who made landfall near Weipa in Queensland in 1606 when charting the south coast of New Guinea. By the time Cook set sail, the Dutch were familiar with the Australian coastline between Cape York and modern Ceduna, South Australia. Their legacy can be seen in a smattering of Dutch place names up and down the west coast—among them Arnhem Land, Cape Leeuwin, and Rottnest Island. Abel Tasman had landed on Tasmania, which he named Van Diemen’s Land for Governor-General Anthony Van Diemen of the Dutch East Indies, and New Zealand, which he named for the Dutch province of Zeeland. The Dutch named the entire continent New Holland, but found nothing there to excite their commercial interests and made no effort to colonise it. Cook wasn’t even the first Englishman to visit Australia—that was William Dampier in 1688, who visited the west coast on his circumnavigation of the world and concluded that the place was generally terrible. Cook was the first European to visit the east coast and land in modern New South Wales. And the British Government was obviously keen to exert its claim on the Australian continent over the Dutch, which explains why the early Dutch explorers have often received short shrift in traditional Australian history.

But if we can generally agree on the facts, we can’t agree on what they mean. Cook’s first voyage of discovery was a remarkable achievement of navigation which added greatly to the world’s store of scientific knowledge. Cook had an impressive career, rising from humble origins in Yorkshire to become one of the greatest explorers of all time. His exploration of eastern Australia facilitated British colonisation of the continent, which has had a terribly destructive impact on indigenous Australia, and the continuing gap in standard-of-living measures between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians remains deeply troubling.

All this leaves Cook, through no fault of his own, in a bit of a historiographical limbo. “There is no doubt Cook was complex, both morally and in legacy” wrote Paul Daley in the Guardian. “He was the foremost British navigator and cartographer of his epoch, a man who was not born to the admiralty and made his way to the top through merit,” but in commemorating his arrival, “Australia should not omit his role in the suffering that followed.” Or as Patrick Stokes, a Melbourne academic, wrote in the New Daily: “Cook’s voyage was indeed a major feat of navigation (remarkably, Cook didn’t lose a single man to scurvy) and an important scientific venture. Even so, it’s hard to see why the Australian government would earmark $48.7 million to celebrate science done 250 years ago by personnel from another nation.” In fairness to the federal government, a significant part of the $48.7 million is going to indigenous causes. As the prime minister put it, the purpose of the commemoration is to offer new generations an insight into Captain Cook, the Endeavour, and the experiences of Indigenous Australians. But the question mark hanging over the event remains.

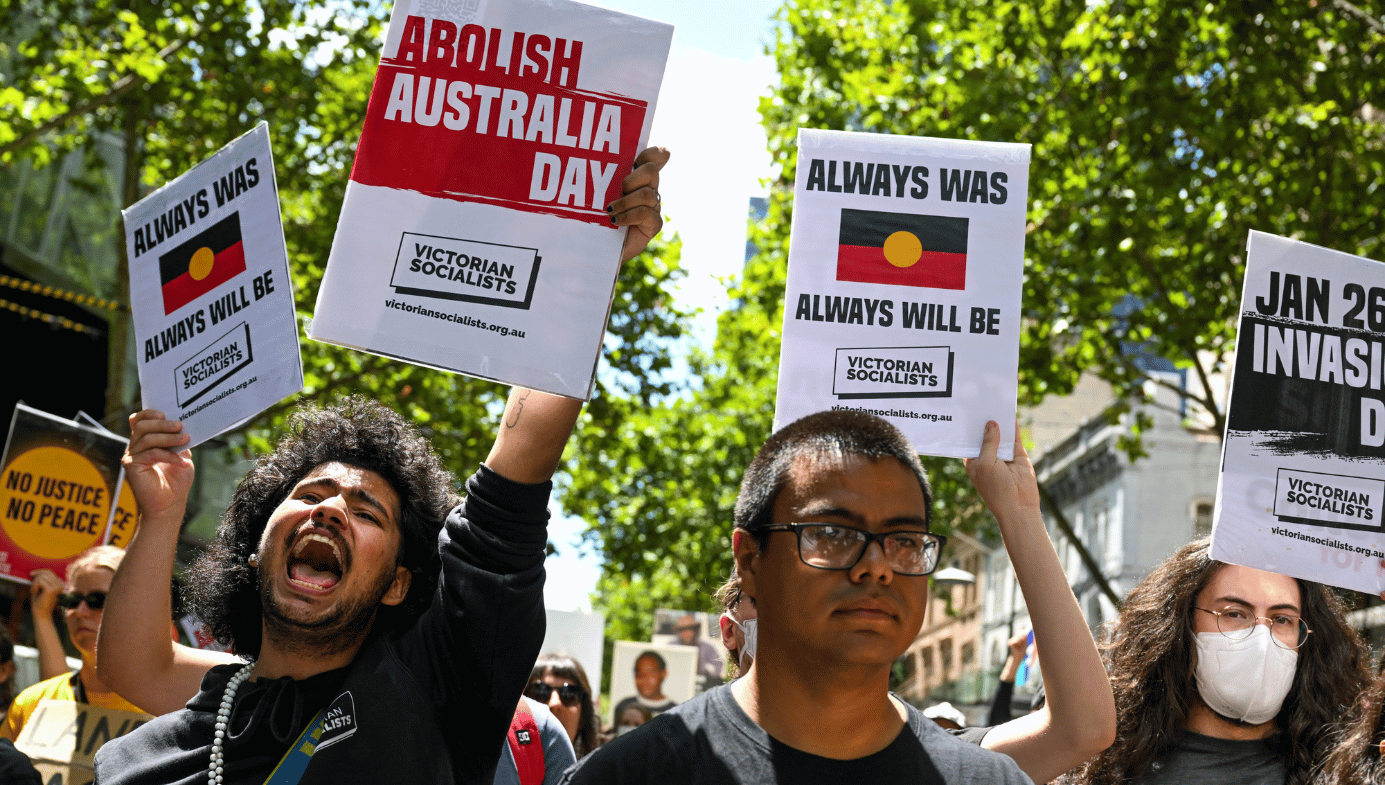

Cook didn’t colonise Australia, nor advocate for its colonisation. but his exploration of the east coast obviously allowed it to take place. When he was sailing, Britain was not in the market for a new colony, although for obvious reasons, it would be in the 1780s. Cook died in 1779 and the First Fleet landed at Sydney in 1788. On January 26th, specifically, a date now commemorated as Australia Day. There is a move to change our national holiday away from a date for which indigenous Australians do not have fond memories. And Captain Cook seems to find himself dragged into it by both sides. In 2018, Deputy National Party Leader Bridget Mackenzie defended retaining the January 26th date, telling Sky News: “That is when the course of our nation changed forever. When Captain Cook stepped ashore. And from then on, we’ve built an incredibly successful society, best multicultural society in the world.” On the other side of politics, the office of Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young released a statement saying: “Despite an important national debate about changing the date of Australia Day away from Captain Cook’s landing at Botany Bay, the government has decided to spend taxpayer money it is stripping from the ABC on yet another monument to Captain Cook on the land of the Dharawal people.” The senator explained that she had not read the statement before it was released. On January 26th, 2019, a young Australian woman protesting in London told the media that “we are here today protesting against Australia Day, which marks the day that Captain Cook landed in Australia.” So, through a combination of reasonable abbreviation and historical ignorance, Cook has become a symbol of the British colonisation of Australia.

In August 2017, a statue of Cook in Hyde Park was defaced with the slogans “Change the Date” and “No Pride in Genocide.” This was, without a doubt, directly inspired by the debate over Confederate memorials then taking place in the United States. Australian political protestors, of all sides of politics, tend to slavishly follow the lead of our American cousins but on a much smaller scale (see the recent COVID-19 lockdown protest in Melbourne for another example). Cook’s case, though, is not as simple. The Confederates fought the US Army to preserve a breakaway government which primarily existed to preserve slavery (as the Confederate vice president himself acknowledged). Cook died before Australia as a country even existed, and his chief claim to fame is as an explorer rather than a soldier or conqueror. Cook was not a King Leopold, known mainly for colonial repression. It would be much simpler if he had been.

Cook’s voyage

The facts of Cook’s first voyage are interesting in their own right. James Cook was born in a Yorkshire village in 1728, worked as a shop-boy, but felt the pull of the sea. He started in the merchant navy on trading ships in the Baltic. In 1755, with Britain preparing for the Seven Years’ War against France, he joined the Royal Navy as an able seaman. His service in the war (1756 – 1763) was distinguished, and he quickly drew the attention of his superiors for his exceptional abilities as a navigator and cartographer, which were remarkable given his lack of formal education. His mapping of the entrance of the Saint Lawrence River facilitated General Wolfe’s successful assault on Quebec in 1759, while the charts of Newfoundland he produced continued to find use into the 20th century. He was promoted to master, then, at age 39, to lieutenant—one of the few who managed to rise to the ward-room from the ranks.

With the coming of peace, the British government was able to turn attention again to exploration. Particularly in the South Pacific, where the maps were still largely blank, and a theoretical Terra Australis Incognita, or southern unknown land, might be found. The Royal Society, Britain’s premier scientific body, was also keen to send an observer to see the 1769 transit of Venus across the Sun. An accurate observation of the transit from different locations around the world would allow them to calculate the distance between the Earth and the Sun. The Navy purchased a sturdy little collier called the Earl of Pembroke which they renamed Endeavour, and appointed Cook to command the expedition based on his proven skills as a navigator and cartographer. The Endeavour set sail from Plymouth on August 26th, 1768, carrying 94 people and bound for Tahiti via South America.

At Tahiti, Cook, astronomer Charles Green, and Solander took measurements of the transit. Cook then opened his second set of secret orders which directed him to proceed south and west, towards the furthest points reached by Tasman in his 1642 voyage, and see if New Zealand might be part of Terra Australis. The instructions directed him “with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.” They advised him to seek to make friends with any natives he encountered, but warned him to be on his guard against surprise attacks.

Cook was sceptical of the existence of Terra Australis, but duly proceeded south and west until he reached New Zealand, which he completely circumnavigated and mapped over the summer of 1769 – 1770. At this point, his instructions were fulfilled—he had proven that New Zealand was an archipelago and not part of an unknown continent. But he decided to return to Europe via the uncharted east coast of New Holland. This was actually something of an afterthought—Cook and his officers were unwilling to remain in southern seas in the oncoming winter, which ruled out proceeding directly to Cape Horn or to the Cape of Good Hope and further searching for Terra Australis in more southerly waters.

Cook crossed the Tasman, striking the Australian coast at Point Hicks, Victoria, on April 19th, 1770. He then proceeded north, landing at Botany Bay. The expedition nearly ended in disaster when the Endeavour was holed by coral off the Queensland coast, but she was repaired. Cook managed the remarkably difficult passage of the Great Barrier Reef, and at Possession Island, claimed the east coast of New Holland for Britain and named it New South Wales. Nobody knows why he picked the name.

Cook undertook two further voyages of exploration. On his second, from 1772 to 1775, he circumnavigated the world at a low latitude, making the first-ever crossing of the Antarctic Circle. He proved that Terra Australis did not exist, or if it did, it was so far to the south that it must be encased in ice and of little value for trade or colonisation. He was then promoted to post captain. On his third voyage, from 1776 to 1780, he charted the west coast of North America from Oregon to the Bering Strait, and became the first European to visit Hawaii.

Cook was undoubtedly a humane man, but his people skills were questionable. His encounters with indigenous peoples, while well-intentioned, were often extremely clumsy. The face-off with the two Gweagal warriors at Botany Bay is an example—it’s hard to imagine how he expected the Aborigines to react to a group of unknown armed men arriving at their village, yelling in a foreign language, and throwing nails. At Hawaii on his third voyage, this clumsiness would have fatal consequences. Cook attempted to resolve a dispute between his men and the Hawaiians by kidnapping King Kalaniʻōpuʻu. The plan failed, and on February 14th, 1779, Cook was hacked to death by Kalaniʻōpuʻu’s retainers. They nonetheless held Cook in high enough regard to give him a traditional funeral.

Britain had been in the habit of sending its felons to its colonies in America. With the loss of the American colonies this was no longer possible, and the gaols and hulks began to fill. The end of the American War in 1783 and the discharge of thousands of men from the Army and Navy didn’t help matters. Joseph Banks and James Matra, a naval officer who had sailed with Cook as a midshipman, lobbied the British government to found a settlement in New South Wales. Needing somewhere to send the convicts and tempted by the (albeit limited) commercial and strategic possibilities of an Australian colony, Home Secretary Lord Sydney agreed, and so the First Fleet was prepared and launched. When the Union Jack was run up at the site of the city now bearing Lord Sydney’s name on Australia Day 1788, the colonial history of Australia began.

The colonial paradox

There are many uncomfortable truths in Australian history. One is the destruction of Aboriginal Australia and the appalling violence which accompanied it. We will obviously never know how many Aboriginal people lived in Australia before colonisation—probably somewhere between 315,000 to one million, with three-quarters of a million being a commonly-cited estimate. But we do know that, at the time of Federation in 1901, there were only around 117,000. Introduced diseases such as smallpox took a devastating toll. Others starved from the loss of their hunting and foraging grounds. But tens of thousands were killed outright by settlers, many of whom were ex-convicts. The original estimate of historian Henry Reynolds was 20,000 Aboriginal dead on the Australian frontier, and modern mainstream historians put it at closer to 40,000. The number may very well be higher. Two recent historians, Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen, combed through the available records and came to a figure of 41,040 Aborigines killed on the Queensland frontier alone. Killing Aborigines in colonial Australia was a crime, but Aborigines were prohibited from testifying in court. During a debate on the question in the New South Wales legislature, one of the founding figures of Australian democracy, William Charles Wentworth, infamously compared allowing an Aborigine to testify to allowing an orangutan to take the witness box. So prosecuting these massacres was extremely difficult. The successful prosecution of the Myall Creek massacre in 1838 is an exception, as a white man was willing to testify for the state. The Massacre Map—the result of a collaboration between the Guardian, the University of Newcastle, and Melbourne University—paints a bloody picture across the continent from the beginnings of white settlement to the Coniston Massacre of 1928.

Some recent historians have challenged this grim picture of frontier violence, such as Keith Windschuttle in The Fabrication of Aboriginal History Volume One: Van Diemen’s Land 1803–1847 (2002). Windschuttle argues that the conventional view of violence on the Tasmanian frontier is unsupported by the evidence. I personally don’t find his argument persuasive, and it doesn’t address the known large-scale killings on the mainland. Nor does it ever seem to have been a mainstream view in colonial times. “There is black blood at this moment on the hands of individuals of good repute in the colony of New South Wales of which all the waters of New Holland would be insufficient to wash out the indelible stains” wrote Reverend John Dunmore Lang darkly in his 1834 history of the colony. At the ceremony for the foundation of Canberra in March 1913, Attorney-General Billy Hughes bluntly noted that “the first historic event in the history of the Commonwealth we are engaged in today without the slightest trace of that race we have banished from the face of the earth.” He went on to warn: “We must not be too proud lest we should, too, in time disappear. We must take steps to safeguard that foothold we now have.”

There is ongoing debate as to whether the colonial treatment of Australian Aborigines would have constituted genocide under the modern definition. I am hesitant to accept this. The 1948 Genocide Convention requires “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” and the British government and its successors in Australia never intended to destroy the Aborigines. But even if they are only guilty of sins of omission, they are still grievous sins indeed. Unleashing thousands of armed ex-convicts on the frontier and then denying the Aborigines the effective protection of the law could only have had one outcome. We hardly let the Chinese Communist regime off the hook for the deaths caused by the Great Leap Forward because they weren’t intended.

After colonisation, the Aborigines became wards of the state, and were subject to various injustices and indignities through the 20th century. They could be forced to live on missions and compelled to seek permission to work, travel, or marry. Their children could be taken without evidence they were abused or neglected. Lorna Fejo, a Warumungu woman, described the experience of being forced onto a truck by the “welfare men” at Tennant Creek in 1932 while her screaming mother clawed at the sides. She was four years old, and would never see her mother again. As late as 1972, Aborigines in Queensland could have their wages arbitrarily confiscated by the government “for their welfare”—the survivors finally came to a legal settlement with the state to recover some of the money in 2019. This is not ancient history, and we must be able to acknowledge it openly if there is to be any progress on indigenous policymaking in Australia.

There is a second uncomfortable truth which sometimes gets raised in these debates—Aboriginal Australia was not some peaceful and harmonious idyll before European contact. Ironically, one of the first people who took this erroneous view was Cook himself. Reflecting on the indigenous Australians in his journal, he wrote, “[I]n reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholy unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniencies so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life; they covet not Magnificent Houses, Houshold-stuff, etc.”

There are diverse people and cultures across the wide Australian continent, so it’s impossible to generalise, but many Aboriginal groups practiced strict religious laws enforced through violence, punishments such as spearing, the arranged polygamous marriages of pubescent girls to older men, and other practices we find abhorrent today. Australia was no stranger to conflict before 1788, and Aboriginal groups had fought, dispossessed, and killed each other across the continent for millennia. Historian John Connor writes extensively on traditional Aboriginal warfare in the first chapter of The Australian Frontier Wars, 1788–1838 (2002). And some of the worst frontier violence against Aborigines was committed by black trackers in government service. Anthropologist David McKnight spent years observing the people of Mornington Island beginning in the 1960s, when there were still people alive who remembered their way of life before the before the first Christian mission in 1914. His resulting book, Of Marriage, Violence, and Sorcery: The Quest for Power in Northern Queensland (2005) paints a sympathetic but also realistic picture of traditional Aboriginal society. Nomadic hunter-gatherers live different lives to settled people. We are surprised, when reading Cook’s account of his encounter with the Gweagal, that they left children behind when they fled. Hunter-gatherer peoples would not find it unusual. Some Aboriginal cultural practices may contribute to problems faced in Aboriginal communities today. It is valid to ask, for example, the extent to which traditional views towards women contribute to the fact that indigenous women are 34 to 80 times more likely to experience domestic violence than non-indigenous women (but also valid to point to the damage done by the destruction of Aboriginal society, including traditions and customs which protected women and children). Taking a critical view of indigenous religion or culture is no more racist than taking a critical view of Christianity or Western culture—every society has cultural baggage and no human society is fixed and unchanging.

White progressives may find this topic uncomfortable, but there is no need to. The Australian Aborigines were no more superstitious and violent than any other people living in a pre-modern society. All our ancestors lived the same way for most of human history. My own forebears in northern Europe worshipped sacred trees and practiced human sacrifice. Great Britain had made significant advances in human rights in the 18th century, but it still presided over an empire where people were hanged in public for petty crimes, Irish tenant farmers kept in poverty and servitude, and slaves lashed to death in the West Indies. Surviving for tens of thousands of years in some of the harshest environments in Australia is no insignificant feat. When the Pintupi Nine, the last uncontacted Aborigines, first encountered white society in the Gibson Desert in 1984, they were found to be exceptionally fit and healthy even though they lived in a region where people struggle to survive today even with all the benefits of modern technology. Aborigines did not farm and so could not build towns or cities, but even with modern farming techniques, the only native Australian plant or animal which has been successfully domesticated on a commercial scale is the macadamia nut. They were not a deficient or inferior people. We can acknowledge the brutality inflicted on the Australian Aborigines without idealising them, wanting to live like them, or insisting that their way of doing things was better than ours. It must be possible to discuss Aboriginal affairs without falling into the trope of either barbaric or noble savages if we are to make genuine progress on reconciliation.

There is a third uncomfortable truth, and it’s a big one. Without the conquest and dispossession of the Aborigines, this country would not exist in any form recognisable to its inhabitants today. Any Australian who feels pride in Australia’s multicultural success story, high standards of living, peaceful politics, or liveable cities, feels pride in something which could never have come into existence without bloodshed. Australia could never have been colonised peacefully by any foreign power. There is no human society in history whose men would not fight to defend their land from an invader, and the Australian Aborigines are no exception. The two Gweagal warriors who stood their ground against Cook were the first but not the last. And there is no way warfare between the Aborigines and British settlers would have resulted in anything other than the spilling of torrents of Aboriginal blood. This is the colonial paradox—we can only regret the violent dispossession of the Aborigines so much, otherwise we become hypocrites. My parents had a dysfunctional marriage, and in one sense, it would surely have been better if they had never met. But if they hadn’t, I wouldn’t exist, so how much can I reasonably regret that they did?

Here’s another way to look at the paradox. In its historic 1992 judgement on Aboriginal land rights, Mabo v Queensland (No 2), the High Court of Australia briefly considered whether the British acquisition of sovereignty over Australia was legal. But it then, quite rightly, pointed out the question was beyond its jurisdiction. If the British claim to Australia was not legal, then the British parliament had no authority to pass laws relating to Australia, including the act giving effect to the Australian Constitution which gives the High Court its power in the first place. Hence, if the court found the British colonisation of Australia illegal, it would be ruling that it was itself entirely illegitimate and its rulings should be ignored. So here we are.

I have written before about the dangers of reading history through a partisan lens. There is no point carrying a brief to either prosecute or defend the British Empire—we can both acknowledge its achievements and recognise its victims. The story of Australian history is one of remarkable success—a colony established an unprecedented distance from its parent country on an unforgiving continent with a founding population of convicted felons grew to become one of the world’s richest, freest, and most stable nations. And the people who live in this country benefit from land taken from its original inhabitants by force.

My family is one example. My grandmother’s great-grandfather was convicted of housebreaking at the Dublin Assizes in 1819. A century before he would certainly have been hanged. Due to an Enlightenment push to make the criminal justice system more humane, he was instead sentenced to seven years’ transportation to New South Wales. He served his sentence, was emancipated, and settled near Ballarat. He ended up living a far better life than he would have as an Irish tenant farmer, and never endured the Potato Famine and Black ’47. But he lived it out on land from which the Wiradjuri people had been driven by the men of the 40th Regiment of Foot.

Conquest is a fact of history. Modern Britain, for example, is a product of the Norman Conquest of 1066. But there’s no great separation in life outcomes between Anglo-Saxons and Anglo-Normans today. Sir Walter Scott’s verse in Ivanhoe where he has an Anglo-Saxon character lament “Norman saw on English oak/On English neck a Norman yoke/Norman spoon to English dish/And England ruled as Normans wish” is a historical curiosity today. By contrast, indigenous Australians have twice the infant mortality rate, two-thirds the employment rate, and a life expectancy around eight years lower than non-indigenous Australians. The figures around incarceration are shocking—while they make up two percent of the Australian population, they make up 27 percent of the prison population. As a non-indigenous Australian, I can ignore the country’s history if I choose. Most indigenous Australians don’t have this luxury, as they live with its consequences daily.

On my first visit to Alice Springs, I was genuinely confronted by the state of the town’s indigenous residents. I never saw one working in a shop, nor did I ever see a black and white person speaking to one another in the street. Most of the Aborigines were clearly in a state of abject poverty, shuffling to and from their camps around the town or sitting huddled in groups beside the road. It was as if the Aborigines and white people existed in different dimensions, invisible to one another. I said hello to an Aboriginal man, and he ignored me. Given their history, it’s not surprising that they should be suspicious of or hostile towards white people. Needless to say, the prospects for a child born into this sort of environment are terrible. As somebody who never forgets the advantages of being born an Australian citizen, it troubles me that others born here will never experience those advantages through no fault of their own.

These are not simple problems, and I have no solutions. A great deal is being done to close the gap, with mixed results. In 2015 – 2016, Australian federal, state, and territory governments combined spent $44,886 for every indigenous man, woman, and child— twice the per capita expenditure on non-indigenous Australians. There have been improvements in some areas—66 percent of indigenous Australians finished high school or equivalent in 2018 compared to 45 percent in 2008—but little progress in others. This is not a criticism of government or indigenous leaders, who have done their best on what is an extremely difficult and complex problem. Much of the money spent on indigenous affairs has gone towards the salaries of white middle-class public servants, but any that I’ve met have been genuinely working diligently to improve indigenous lives. So far, though, every high-level policy on indigenous affairs seems to have failed.

In these circumstances, it’s perfectly understandable that many indigenous Australians don’t consider Cook’s arrival to be worth celebrating. Personally, I think Cook is best understood as a quintessential figure of the European Enlightenment, with all the consequences flowing from that, positive and negative. I can say for certain that we should be better-informed of our history, both indigenous and colonial, because it tells us both why our country is successful and gives the background to many of the problems we still face. I hope, above all, that we can achieve real improvement in the welfare of indigenous people. Then, we might be able to calmly accept the colonial paradox and find a lasting place for Cook in our national story.