Books

Decadence and Depravity in Louisville, Kentucky

The publication of his electrifying dispatch from the Kentucky Derby on May 2nd, 1970, had announced him as among the most innovative and powerful voices in American letters.

Fifty years ago today, Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman drunkenly negotiated the pitfalls of Louisville’s Churchill Downs, home of the world-famous Kentucky Derby. At the time, Thompson was a moderately successful writer who had published an acclaimed book a few years earlier about his time among the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang. Steadman was a talented young artist from Wales who had traveled to the United States in search of work.

For Steadman and Thompson, it would be their first meeting, but it was hardly Thompson’s first derby. He had grown up in Louisville’s Cherokee Park area and was familiar with the whisky gentry who would be in attendance. As a teenager, Thompson’s wit, charm, intellect, and surly insubordination had made him popular among the city’s wealthy young men and women. However, he had never felt fully accepted and, when he was arrested along with a couple of classmates for holding up a car just shy of his graduation, his rich friends abandoned him to his fate—two months in prison.

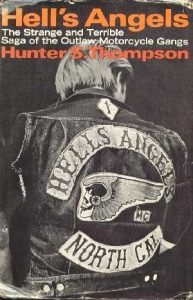

After 10 years of surviving as a journalist, Thompson’s big break arrived in 1965, when he accepted an assignment from the Nation to investigate the rise of motorcycle gangs. The resulting article was a huge success, and offers from magazines and publishing companies began to pour in. In 1967, his first book, Hell’s Angels, was released to reviews that gushed over his wit and courage, and soon he was a hot literary talent. Despite the offers that came his way inviting him to file follow-up articles and book proposals, his literary output between 1967 and 1970 was not prodigious. However, in the few pieces of writing that he did publish, his prose style was already developing in a radical direction.

In 1969, Thompson was commissioned by Playboy to write an article about champion skier, Jean-Claude Killy. He followed the skier around for months but found nothing to say because Killy appeared to have no personality whatsoever. It was Killy who finally suggested that Thompson write about how difficult it was to write about him. Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention, and this unorthodox approach became Thompson’s new working model—getting the story was the story. When Playboy rejected the article and told Thompson that he would never write for them again, Warren Hinckle at the new and short-lived progressive journal Scanlan’s picked it up instead.

It was another huge success, so when Thompson called Hinckle at three o’clock one morning in April 1970 and said he wanted to write a feature about the Kentucky Derby, Hinckle readily agreed. Thompson had been having dinner with his friend, Jim Salter, in Aspen, Colorado, when the subject came up. Salter had asked him if he was planning to attend the derby and Thompson said he wasn’t. After the spell in jail that had cost him his high school diploma, Thompson had joined the Air Force and considered his escape from Louisville to be more or less permanent. He did not particularly feel like going back to rub shoulders with the people who had looked down on him and, finally, turned their backs as he wept in a lonely courtroom.

Thompson was a night owl and, after dinner, he stayed up pondering Salter’s question. Maybe it was time to go back and see the derby. It might be the sort of thing he could write about: the outsider returns after more than a decade on the road. This needn’t be a dull article for a conservative newspaper or magazine, which was the sort of work on which he’d cut his teeth in the early Sixties. So, he called Hinckle up in the middle of the night and asked if he would pay for a flight to Kentucky plus expenses. “The story, as I see it,” he explained, “is mainly in the vicious-drunk Southern bourbon horse-shit mentality that surrounds the derby than in the derby itself.”

Thompson’s writing was already beginning to resemble what readers would later come to call Gonzo journalism. He tended to insert himself into the prose as observer and participant, embark on weird and irrelevant digressions, recount conversations and events that probably never happened, discard any pretense of objectivity, lurch erratically in and out of hyperbole and paranoia, and dust his prose with a litany of stylistic quirks and a peculiar lexis that included words like “atavistic,” “swine,” “savage,” and “doomed.” It was a subjective, chaotic, and messy approach to journalism unsuited, Thompson felt, to the blank objectivity of a photojournalist’s camera. So, he asked Hinckle to assign him an illustrator instead.

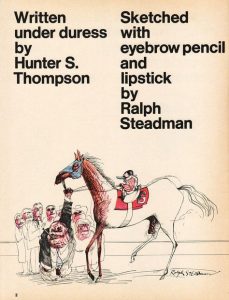

Ralph Steadman was one of the best young cartoonists in Britain and, just like Thompson, had a wonderful talent for bringing out the inner ugliness of his subject. Neither of them liked to dress a subject up and make it look pretty; they preferred to identify a flaw and blow it out of all proportion. The art director at Scanlan’s had heard that Steadman was looking for work and called him up. On the way to the airport, he realized he’d forgotten his artist’s toolbox. He stopped briefly at the home of one of the magazine’s editors to scavenge what he could and left with eyebrow pencils and lipstick.

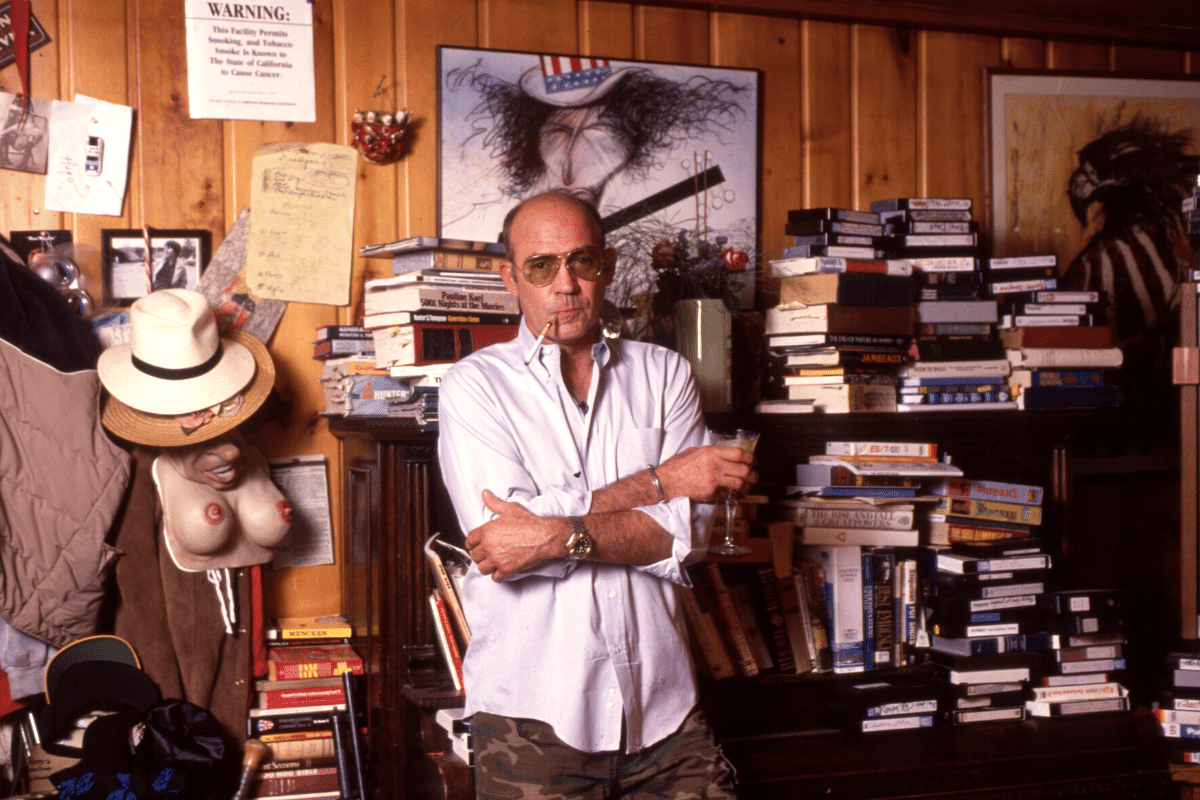

Among the Kentucky Colonels, Thompson and Steadman stood out like sore thumbs. Fresh from his failed Freak Power campaign for sheriff in Aspen the same year, Thompson was sporting a shaved head. He was also tall, handsome, and usually dressed in bright clothes. Steadman, on the other hand, had long hair and a wild beard. The two men should have found it easy to locate one another, but somehow it took them two days before they finally met in the press room. They immediately set about drinking and did not stop until several days after the race.

When eventually it came time to leave Louisville and produce the article and illustrations, Scanlan’s brought both writer and artist to New York and had them hole up at the Royalton Hotel. It took Steadman two days to complete his illustrations, but Thompson found himself confronted with a brutal case of writer’s block. He lay in the bathtub, slugging whisky from the bottle, and awaiting inspiration. Eventually, his frantic editors called and demanded something. The magazine was due to go to press and there was still a huge hole in the middle of the issue where Thompson’s story was supposed to go. Thrown into a panic, Thompson ripped pages out of his notebook and handed them to the copyboy. Hinckle called and declared it brilliant. Within an hour, the copyboy was back for more, and Thompson’s story appeared as scheduled in the next issue beneath the eye-catching headline “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.”

Thompson later admitted that he felt guilty and ashamed about his failure to write the article. The magazine’s editors and readers, however, felt differently. It was, they thought, a triumph. The first half recounts Thompson’s arrival in Kentucky, a prank played on a gullible racist at the airport, and then his meeting with Steadman. The second half is a disjointed but somehow intensely personal account of a day spent staggering around the derby in an inebriated state, terrifying attendees and spraying a restaurant full of patrons with mace. Thompson and Steadman didn’t bother to actually watch the race they had been sent to cover. Instead, they went in search of a “special kind of face” that they hoped would allow Steadman to produce a representatively scathing portrait of Kentucky’s upper class. As they are about to despair of finding someone suitable, Thompson glances in a mirror and realizes:

There he was, by God—a puffy, drink-ravaged, disease-ridden caricature… like an awful cartoon version of an old snapshot in some once-proud mother’s fancy photo album. It was the face we’d been looking for—and it was, of course, my own.

It was a highly unusual piece of writing that trashed the conventions of traditional reporting in favor of a freewheeling rock’n’roll antagonism. It was funny but aggressive, satirical and cruel, and only loosely factual. It was neither exactly journalism nor exactly fiction… it was something in between and something quite new.

* * *

When Bill Cardozo of the Boston Globe called to congratulate Thompson on his story, he called it “pure Gonzo,” a reference to a song Thompson had played repeatedly while he and Cardozo were covering the 1968 presidential campaign together. This became the label affixed to a new literary subgenre that Thompson pioneered and then basically monopolized. Whenever Thompson was asked to define Gonzo journalism, he would say something to the effect of “It’s whatever I do,” and he used the term to distinguish his own work from that of the similar-but-different New Journalism movement. For years, he had attempted to hone his own literary voice and now he had a whole self-invented category to himself. Certainly, no one else has successfully managed to do it without appearing like a crude imitation.

So, Gonzo became a synonym for “the style of writing used by Hunter S. Thompson,” as well as the manner in which he lived his life. His idiosyncratic turns of phrase helped to make his style immediately identifiable, but the use of raw notes was his most distinctive innovation—an accidental discovery, without which Gonzo reporting would simply not have existed. The experience of writing about the Kentucky Derby, he said, taught him the value of “impressionistic” journalism. Writing at the scene of a story in real time, and submitting the unedited copy for publication, he came to believe, produced a more immediate and honest sort of reportage. With patient and indulgent friends like Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner and Hinckle at Scanlan’s supporting him, Thompson decided that he was finished with traditional journalism and would henceforth experiment with fact-fiction hybrid forms.

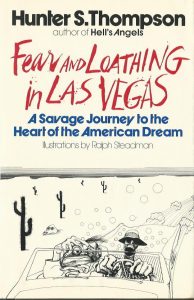

Interestingly, Thompson always maintained that the book for which he became most famous was “a failed experiment” in Gonzo journalism rather than the genuine article. While investigating the killing of a Chicano journalist named Ruben Salazar for a lengthy essay entitled “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” Thompson fled to Las Vegas with his friend, the attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta. There, the pair (may or may not have) indulged in the copious consumption of psychedelics, an activity they repeated when they returned to Vegas a month later to cover a district attorneys’ conference convened to discuss the nation’s drug problem. In his spare moments, Thompson began to tie these events into the very loose plot of a book. Eventually, this project became Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, one of the era’s most famous novels about drugs and drug abuse, and perhaps the first to offer an epitaph for the Sixties’ counterculture. It was not, however, a work of spontaneity but the labored result of four or five drafts and many months of hard work.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was first serialized in 1971 by Rolling Stone and then published as a short book in 1972. Heavily inspired by J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, it offers a wild, shocking, and frequently very funny report of Thompson alter-ego and sports journalist Raoul Duke and his attorney running amok in America’s most debauched city. From between the lines, however, it yields a satire of contemporary American values indicated by its subtitle “A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” The book’s black humor, hip countercultural references, belligerent prose, and extravagant tales of anarchy and excess made it an instant cult classic among those sick to death of Nixonism. Throughout his subsequent career, Thompson would be accused of re-hashing the plot of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, visiting events like the Super Bowl and churning out basically the same story. But it was actually the Kentucky Derby commission for Scanlan’s that provided the template for everything that came after.

By 1970, Thompson had figured out that he needed a companion who could aid his own introduction to his readers—a foil with whom he could bat ideas back and forth. And if this companion were a friend of his, he could just make up the dialogue later and no one would question it. For the Kentucky Derby story, this role was filled by Ralph Steadman, and for the Las Vegas story he used Oscar Zeta Acosta. In both cases, he played up their foreignness, even though Acosta was an American. This allowed him explain the ins and outs of Kentucky high society to Steadman (a naïve and overwhelmed Englishman) and to extemporize to Acosta (transformed into a 300-pound Samoan) on the theme of American corruption and greed.

And in both pieces, Thompson used his antihero protagonists to caricature the behavior he wanted to criticize. By acting like a vicious, slobbering drunk in Kentucky, Thompson had become a part of the fabric of the derby, and now, in Las Vegas, he could stagger through casinos in a frenzy of LSD and adrenochrome and be cordially welcomed, excused, and even extended credit. Neither narrative had much in the way of a plot, and the events Thompson had been sent to cover were quickly forgotten. In the Kentucky story, he doesn’t bother to find out who won the race, and in Las Vegas, he can’t see the Mint 400 motorcycle race he has been paid to cover through the sandstorm the bikes kick up. Almost everything Thompson wrote after 1970 would be stories of hotel rooms, fax machines, and deadline pressure, and escapades of vaguely allegorical importance. The process became the point.

Throughout the sixties, his writing had drifted from an idiosyncratic but basically conventional approach until he had hit upon his own ferociously original take on the kind of “personal journalism” that had first been pioneered by Jack Kerouac. Kerouac’s On the Road, Thompson believed, shattered an obsolete distinction between fiction and non-fiction that belonged in the 19th century. Even in his older works, Thompson had taken care to insert not just his opinions but also his persona—the shorts and sneakers, the Hawaiian shirt, and the cigarette holder. He was aware of the myth he was creating of the drug-crazed outlaw journalist and confected and exaggerated his rebellious exploits to add to his legend, even when there was no journalistic reason to do so.

* * *

Although some fans and critics prefer the similarly titled follow-up, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, it is generally agreed that Thompson’s writing never again scaled the heights of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and its prototype “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.” From the mid-Seventies onward, his output became progressively weaker. Thompson had always struggled with the self-discipline required of a productive writer, a characteristic that drove his editors to distraction. But a number of observers have speculated that this problem was significantly aggravated by burgeoning cocaine consumption.

Despite his reputation as a sybarite, Thompson mostly smoked cigarettes and slugged beers while writing. Recreational drug use was generally reserved for when he was not at his typewriter. However, when David Felton at Rolling Stone asked Thompson to review Sigmund Freud’s Cocaine Papers for the magazine in 1973, he thought it would be dishonest not to try the substance in question and had Felton send him some. Most of the people close to Thompson identify this as the turning point after which drug abuse overwhelmed his ability to write. The Freud review was never published, and Thompson subsequently developed a habit of taking assignments and simply not completing them.

There were also the pitfalls of fame to navigate. After Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Thompson was practically a household name, and his notoriety only grew throughout the rest of the decade. He became trapped in the character of Raoul Duke, particularly after he was satirized in Gary Trudeau’s comic, Doonesbury. Even when he tried to do his job, he found himself hounded by autograph hunters. Fans, journalists, politicians… everyone wanted to meet America’s glamorous outlaw journalist. On one occasion when he was attempting to report on a court case, the judge blurted out, “I’m so honored to meet you, Mr. Thompson.”

He retreated to his “fortified compound” in Woody Creek, Colorado, where he surrounded himself with friends, drugs, guns, and other distractions. Soon he was partying with John Belushi, Bill Murray, Jack Nicholson, Sean Penn, and Johnny Depp. This hedonistic existence was not exactly compatible with a journalist’s deadlines or a novelist’s long meditations. As the years went by, it became harder to recall the days when he had sweated over every word and sentence and paragraph as he redrafted Fear and Loathing. Gonzo had been the breakthrough that allowed Thompson to command vast fees for his increasingly erratic writing and disastrous speaking engagements. He had planned to apply his unique approach to a wide variety of stories, but instead he became trapped in the cartoonish world he had created—what had once seemed so fresh and original soon became stale and repetitive.

He had arrived on the scene with a bang in the first years of the Seventies, but most of what remained of the decade disappeared in a blur of disappointment and failure. He flew to Zaire to cover one of the biggest sporting events of the century, “The Rumble in the Jungle,” and spent several weeks taking drugs instead of trying to get face time with Muhammad Ali or George Foreman. Hours before the fight, Ralph Steadman found Thompson in a swimming pool, clutching a bottle of scotch and surrounded by chunks of floating marijuana. The pair of them had been paid by Rolling Stone to report on the fight, but Thompson had sold their tickets.

A year later, he flew to Vietnam to cover Saigon’s fall to the North Vietnamese, but days before the city fell, he fled to Hong Kong. He refused to hand over what little writing he had managed to produce to the Rolling Stone editors, and it was 10 years before his report was eventually published. In the Eighties, Jann Wenner managed to entice Thompson to cover the US invasion of Grenada, and was rewarded with the same fiasco. A trip to New Orleans similarly turned into a week’s abuse of his publisher’s credit cards, with not even a half-baked article to show for it at the end.

This kind of behavior became normal for Thompson. Long-suffering friends like Wenner who had tolerated his tantrums and abuse and chronic unreliability finally ran out of patience. Few editors would dare hire him, and those that did found that he would take vast sums of money and then simply not turn in any work. Sometimes he tried hard and failed, and other times he just did not try at all. When he did manage to file copy, it was frequently so unintelligible that his editors would have to work for days patching fragments of disordered prose into something comprehensible. From a bottom-line point of view, it was usually worth the effort because his name still sold copies and his fans did not much care what he turned in. But the decline in quality was steep.

Ideas for books and movies also fell by the wayside as Thompson squandered one opportunity after another—he’d become temporarily obsessed with a plot idea and then just forget about it and move on to something else. In the 1980s, he wrote The Curse of Lono, probably the last piece of longform work he produced of any note. The book was another fact-fiction hybrid based around the Honolulu Marathon and it took Thompson several painstaking years to write. In the end, however, there was so little useable material that the publisher had to pad out the book with long quotations from other sources in the public domain and Steadman’s illustrations. It was even printed on unusually thick paper to make it seem more substantial.

In his later years, Thompson found that he could make money and satisfy his fans by releasing old material, such as the two dense volumes of letters covering the period, 1955 – 1976. But his contemporary writing was mostly abysmal. There were a few standout efforts, including the early Nineties stories, “A Dog Took My Place” and “Fear and Loathing in Elko,” but they were still a pale shadow of his work from 20 years earlier. Since the early Seventies, he had struggled to maintain his focus, and now, without the assistance of a good editor, he was unable to write more than a few hundred words without straying into pointless digressions, irritating Thompson mannerisms, and incoherent repetition.

Thompson had started his career as a sportswriter on Eglin Air Force Base in Florida and he ended it writing a sports column for ESPN. The best of these were collected in his final book, Hey Rube, which was published a year before his suicide in 2005. It was another weak book and Thompson knew it—as his physical health declined, he was also painfully aware of his wasted literary abilities. After Gonzo was created, it never evolved. The one-man literary genre was soon washed up, sold out, and left to reflect upon chances missed. Thompson had earned his place in the literary canon with staggering innovations in form, but he burned out and stopped pushing.

As a young man, Hunter S. Thompson had visited Ernest Hemingway’s home in Ketchum, Idaho, to discover what had driven a great American writer to take his own life. He concluded that Hemingway had lost confidence in his voice and was unable to describe a world moving at a frantic pace. Forty-two years later, Thompson found his own reasons. The publication of his electrifying dispatch from the Kentucky Derby on May 2nd, 1970, had announced him as among the most innovative and powerful voices in American letters. But when a great writer can no longer write, and when even the possibility of turning out another great book no longer exists, there is little else to do. It was a tragic end to a life of unfulfilled promise.