COVID-19

Beware Your Innate Pessimist

Coronavirus is deadly, but it is not the bubonic plague, which had a mortality rate of 50 percent.

With the COVID-19 lockdown upon us, anxiety and depression are on the rise. It would be irresponsible to downplay the risks that the novel coronavirus poses to America’s health and economy. But excessive pessimism is also in no one’s interest. Problems and their purported solutions must be evaluated dispassionately. Evidence, reason, and science rather than intuition or emotion must guide us during this difficult moment.

Unfortunately, some of our most basic impulses evolved at a time when the world was very different from the one we now inhabit. “Our modern skulls house a stone age mind,” note Leda Cosmides and John Tooby from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Consequently, that mind can mislead us as we address today’s problems, including those of anxiety and depression, in ways that can have unintended and harmful consequences.

What sort of “habits of the mind” have we developed over the hundreds of millennia we spent living in a world that was more inhospitable than our own?

First, we have evolved to prioritize bad news. “Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce,” wrote the eminent Princeton University psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow. This powerful impulse can deceive even the most dispassionate and rational observers. As Marc Trussler and Stuart Soroka from McGill University in Canada found in their 2014 paper ‘Consumer Demand for Cynical and Negative News,’ even when people insist that they are interested in more good news, eye tracking experiments show that they are in fact much more interested in bad news. “Regardless of what participants say,” the authors of the study conclude, people “exhibit a preference for negative news content.”

Second, as the Harvard University psychologist Steven Pinker noted in his 2018 book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, the nature of cognition and the nature of news interact in ways that make us think that the world is worse than it really is. News, after all, is about things that happen. Things that did not happen go unreported. As he points out, we “never see a reporter saying to the camera, ‘Here we are, live from a country where a war has not broken out.’” Newspapers and other media, in other words, tend to focus on the negative. As the old journalistic adage goes, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

Third, the media seldom provide a “compared to what” analysis or put terrible events in their “proper” context. Coronavirus is deadly, but it is not the bubonic plague, which had a mortality rate of 50 percent, or the septicemic plague, which had a mortality rate of 100 percent. Luckily for the long-term wellbeing of our species, we have been re-awakened to the mortal danger posed by communicable diseases by a far milder virus. Hopefully, human and financial resources will be deployed by governments and the private sector to ensure that next time we are ready. Laws will be changed and regulations streamlined to ensure that we are nimbler in responding to future emergencies.

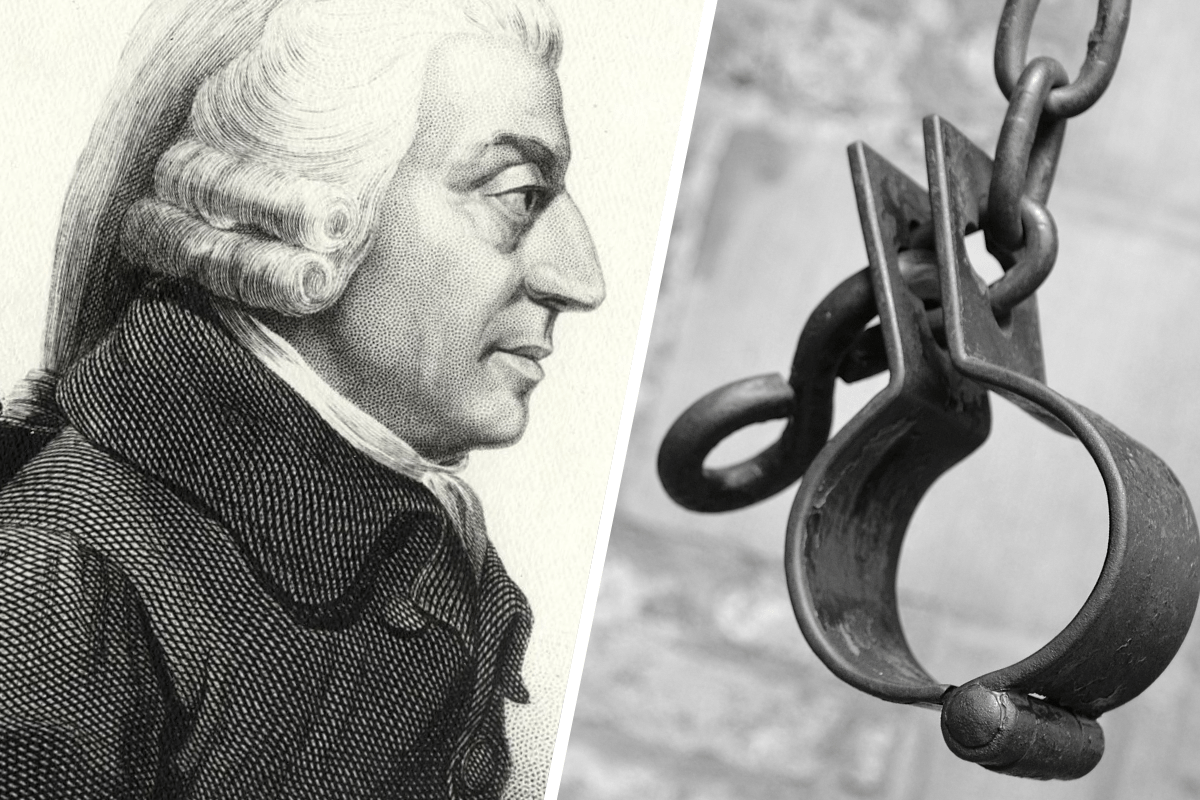

Fourth, the arrival of social media makes bad news immediate and more intimate. Until relatively recently, most people knew very little about the countless wars, plagues, famines, and natural catastrophes happening in distant parts of the world. In 1759, the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

The most frivolous disaster which could befall [a man] himself would occasion a more real disturbance. If he was to lose his little finger tomorrow, he would not sleep tonight; but, provided he never saw them, he will snore with the most profound security over the ruin of a hundred millions of his brethren, and the destruction of that immense multitude seems plainly an object less interesting to him, than this paltry misfortune of his own.

But greater awareness about the suffering of others provided by mass media and the Internet also allows us to come to their assistance and co-ordinate a response. Additionally, the Internet is enabling some of us to work while maintaining social distance, as well as providing countless hours of material to watch and listen to and read as we await the end of lockdown in our homes.

Fifth, the human brain tends to overestimate danger due to what psychologists call “the availability heuristic” or a process of estimating the probability of an event based on the ease with which relevant instances come to mind. Unfortunately, human memory recalls events for reasons other than their rate of occurrence. When an event turns up because it is traumatic, the human brain will overestimate how likely it is to recur. Right now, tens of thousands of people are fighting for their lives with the help of ventilators. Others have lost that fight. While that outcome is tragic, don’t immediately assume that that’s the fate that awaits you. To keep depression and anxiety at bay, bear in mind that tens of thousands of people are on the mend.

Sixth, as psychologists Roy Baumeister from the University of Queensland and Ellen Bratslavsky from Cuyahoga Community College found, “bad is stronger than good.” Consider how much happier you can imagine yourself feeling. Then consider: how much more dejected can you imagine yourself to feel? The answer to the latter question is: infinitely. Research shows that people fear losses more than they delight in gains; harp on setbacks more than they relish successes; resent criticism more than they feel encouraged by praise. Try not to dwell on the worst case COVID-19 scenarios and always remember that, statistically-speaking, most people have a good chance of getting through the pandemic without so much as exhibiting minor symptoms of the sickness.

Seventh, good and bad things tend to happen on different timelines. Bad things, such as the outbreak of a pandemic, can happen quickly. Good things, such as the strides humanity has made in the fight against HIV/AIDS, tend to happen incrementally and over a long period of time. As Kevin Kelly from Wired magazine put it in his book The Inevitable:

Ever since the Enlightenment and the invention of Science, we’ve managed to create a tiny bit more than we’ve destroyed each year. But that few percent positive difference is compounded over decades in to what we might call civilization… [Progress] is a self-cloaking action seen only in retrospect.

To that end, remember that our species has eradicated or almost eradicated smallpox, cholera, typhoid, measles, polio, and whooping cough. We have made great progress in our struggle against malaria and HIV/AIDS. And the speed of our successes is increasing. The earliest credible evidence of smallpox comes from India in 1500 BC. The disease was eradicated in 1980. That’s 3,500 years of suffering. In 1980, we started to learn about HIV/AIDS. By 1995, we had the first generation of drugs that kept infected people alive. That’s 15 years of suffering. The Ebola epidemic raged between 2014 and 2016. The first Ebola vaccine was approved in the United States in December 2019. That’s five years of suffering. Last December, the coronavirus did not have a name. Today, human trials for the coronavirus vaccine are underway throughout the world.

Eighth, humans also suffer from a psychological quirk known by such names as “turning-point-itis,” pessimism extrapolation, or the end of history illusion. As the former Wall Street Journal financial columnist Morgan Housel observed, even people who are aware of the progress that humanity has made in the past, “underestimate our ability to change in the future.” “If you underestimate our ability to adapt to unsustainable situations,” he noted, “you’ll find all kinds of things that currently look bad and can be extrapolated into disastrous. Extrapolate college tuition increases and it’ll be prohibitively expensive in 10 years. Extrapolate government deficits and we’ll be bankrupt in 30 years. Extrapolate a recession and we’ll be broke before long. All of these could be reasons for pessimism if you assume no future change or adaptation. Which is crazy, given our long history of changing and adapting.” Indeed. Humans have changed and adapted in the past and we shall do so and thrive once more.

If we bear these eight biases in mind as we assess the world around us, it can help us to keep our spirits up during this challenging time. Humans, unlike other members of the animal kingdom, are intelligent beings uniquely capable of innovating their way out of pressing problems. We have developed sophisticated forms of cooperation that increase our chances not only to survive, but to prosper. There are, in other words, rational grounds for optimism about the future. And while it is true that, as the financial brokers like to say, past performance is no guide to future performance, recall the words of the British historian and statesman Thomas Babington Macaulay, who wrote in 1830:

In every age everybody knows that up to his own time, progressive improvement has been taking place; nobody seems to reckon on any improvement in the next generation. We cannot absolutely prove that those are in error who say society has reached a turning point – that we have seen our best days. But so said all who came before us and with just as much apparent reason… On what principle is it that with nothing but improvement behind us, we are to expect nothing but deterioration before us?

As we go through the COVID-19 lockdown together, it is important to remember all the different ways in which the human mind can misinform and mislead. We are members of a species that’s always on the lookout for danger and this predisposition toward the negative provides a market for purveyors of bad news. The negativity bias is deeply ingrained in our brains. It cannot be wished away. The best that we can do is to realize that we are suffering from it.