Top Stories

For Gay Men Who Came of Age in the 1980s, a Grim Sense of Déja Vu

Surrounding all of these movements has been the metaphorical connection of disease with not only illness, but also impurity more generally—concepts that have obvious and horrifying linkages to racist political movements.

I don’t remember exactly when I first heard of AIDS—or even what term was being used to describe it at the time. (Some of the first reports in 1982 referred to “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency” and “Acquired Immunodeficiency Disease.”) I’m Canadian, and most of my friends thought the phenomenon was confined to New York City and a handful of other large American cities. They refused to be concerned about it. To the extent it made news in the local media, it was in reports about the sudden appearance of a rare “cancer” in older gay men.

By 1983, documented deaths were occurring in Toronto, where I live. We were told that it was passed on through sex—and, more specifically, through “mucous membranes.” I exhibited the complete ignorance of such matters that is typical of young men. It seemed to me that a penis was not a membrane, but I wasn’t sure. In 1985, when I was interviewed for one of the first Canadian documentaries on AIDS (No Sad Songs), I decried the lack of clear information, asking, in grim jest, “What the f—k is a mucous membrane?”

As pictures of emaciated young men began to appear on television, I grew terrified. The first friend I knew who died of AIDS was Larry Clemson, a beautiful, lanky blonde, and the sweetest boy I’d ever met. I was a little in love with him. The year after we vacationed together in Provincetown, he moved to New York City. Within six months, he was dead.

His last phone call was devastating: “Well, I’ve got it,” he said, in that corny, self-ironic, unpretentious voice of his. “I know I’m gonna die.”

That’s the way it was in those days. I didn’t know what to say. “No, Larry. No.” And then, “I love you.” And then, Goodbye.

Everyone dealt with the fear and terror in their own way. My own strategy as a playwright was dark comedy. And Larry’s death helped inspire Drag Queens On Trial. At the end of the play, Lana Lust is diagnosed with AIDS by The Bad Witch of the West. Instead of being shamed, she defends herself in a melodramatic final speech: “Don’t turn back! Don’t give up! It was worth it!”

In 1988, John Glines, the original producer of Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy in New York City, even tried to produce Drag Queens On Trial. I was ecstatic—for about two seconds.

“Love the jokes,” I remember him telling me. But “you’ve got to get rid of the AIDS stuff. We’ve had enough of AIDS plays.” The gay community was weary of dying, weary of doom.

Some gay men thought the lack of public information about AIDS was part of a systematic homophobic agenda. And my fantastical approach in Drag Queens On Trial was designed to pierce this attitude of surreal conspiracism. Ronald Reagan was then the US President, and his administration didn’t seem particularly interested in AIDS. When White House spokesman Larry Speakes was asked about AIDS in 1982, for instance, he joked: “I don’t have it.” And if you listen to the recording of that press conference, you can hear reporters in attendance laughing repeatedly as Speakes disavows personal knowledge of what some journalists called the “gay plague.”

At the time, public figures were still embarrassed to discuss sexuality in general, let alone gay sexuality. As recently as the late 1970s, singer Anita Bryant had led a high-profile campaign against gay men called “Save Our Children.” (Her goal, she said on one occasion, was to “do away with the homosexuals.”) It took the 1987 death of Liberace—one of the few obviously gay men with a mass commercial following—for many straight people to cast aside such thinking.

When artists deal with the issue of disease, they inevitably enter the realm of symbols. In her 1978 book Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag showed how this can be damaging to the extent it encourages the idea that diseases channel a certain personality type or lifestyle. (Sontag herself had been diagnosed with breast cancer, and was opposed to the idea, then prevalent within certain therapeutic subcultures, that the disease afflicted those who were despondent or otherwise predisposed to a “cancer personality.”) Because AIDS can be transmitted through unprotected sex, the disease was metaphorically linked to the sexualized nature of gay culture itself. And this culture was cast as a form of original sin that was now being punished with death.

Such metaphorical extrapolations were encouraged not just by Christian conservatives, but also by a puritanical sub-culture that always had existed within the gay community. Playwright Larry Kramer, for instance, who’d already excoriated gay male sexual promiscuity in his pre-AIDS novel Faggots, demanded in his plays and articles that we control our libidos. Literary theorist Leo Bersani wrote an essay entitled Is the Rectum a Grave?, describing three HIV-positive children in the deep south who were barred from school for fear they’d endanger the lives of fellow students. Bersani summons to mind the spectre of gay pornography: “In looking at three Hemophiliac children they may have seen—that is, unconsciously represented—the infinitely more seductive and intolerable image of a grown man, legs high in the air, unable to refuse the suicidal ecstasy of being a woman.”

As of this writing, there have been about 15,000 deaths from COVID-19 in the United States. And even an optimistic forecast would put the death toll at close to 50,000 by the time 2020 is over—about the same number of Americans who’d died from AIDS by the end of the 1980s. While the most severe COVID-19 cases typically appear in old people, AIDS victims were predominantly young or middle-aged. And during those early years, more than 90 percent were men. It was only when many straight people (including women) started dying that the public more fully mobilized against AIDS—just as the appearance of young COVID-19 patients in ICUs has energized efforts to fight the current pandemic. Instead of dismissing AIDS as a “gay plague,” some were now predicting that this would become a Biblical-scale pandemic in all sectors of human society. Many people seemed to go from zero to sixty—shameful indifference to full-blown panic—in the blink of eye.

Scientist Stephen Jay Gould, for instance, told New York Times readers in 1987 that the disease “may run through the entire population, and may carry off a quarter or more of us.” That same year, the US Secretary of Health and Human Services said AIDS could prove to make the Black Death “look very pale in comparison.” Congressman Henry Waxman stated that AIDS was the “most serious epidemic we’ve ever faced.”

An article in the New Republic (which then existed as a respected and sober-minded publication) warns of the dangers associated with these apocalyptic predictions: “It is not more stories about the terrors of AIDS—roll calls of the dead, first-person accounts of the agony of dying—that the public needs, but fewer.” The radical disconnect between the real statistics and imagined hysteria was directly related to the potent anti-sex metaphors associated with AIDS. By this time, the state of New York was permitting city governments to close gay bathhouses, even though some doctors warned that these were the only places that many men were provided with accurate health information, condoms, and an opportunity to practice decent hygiene.

Even in Canada, the Supreme Court determined that a person with HIV/AIDS could be found guilty of assault if they had unprotected intercourse without disclosing their HIV-positive status. Thankfully, following the introduction of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis)—a regime that is 99 percent effective in halting the spread of HIV—Canadian authorities eventually realized that criminalizing non-disclosure in this way can sometimes blur into a form of persecution. At the very least, the criminalization of illness may actually discourage people from being honest with their sexual partners—and even with their doctors, since medical ignorance can be used as a legal defence.

No two pathogens are the same, nor are any two pandemics. But there are important analogies between COVID-19 and AIDS that many gay men of a certain age will notice. As with AIDS, COVID-19 was at first dismissed as something that happens to “other people”—with the Chinese playing the role that gay men played in the early 1980s. With COVID-19, the time scale has been greatly compressed. But in both cases, the broad public eventually snapped somewhat suddenly into an immediate panic once it was understood that literally anyone was at risk.

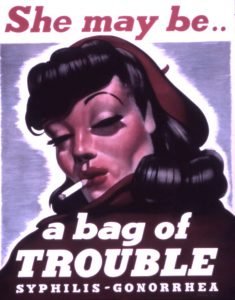

In the United States, COVID-19 was blamed on China (and in some parts of China itself, ironically, the disease is now associated with Italians), adding a layer of bigotry on top of public fear. Syphilis, similarly, was for many years known by the English as a “French” disease. And AIDS was originally associated not only with gay men but outsiders more generally: sex trade workers, drug addicts, and Haitians (and so it did not surprise me to learn that the majority of those arrested in Canada for non-disclosure of HIV diagnosis have been black males). In times of medical hysteria, sexism, too, can come into play: A century ago, US officials targeted thousands of women (many of them perfectly healthy) on suspicion of spreading syphilis and gonorrhoea. Surrounding all of these movements has been the metaphorical connection of disease with not only illness, but also impurity more generally—concepts that have obvious and horrifying linkages to racist political movements.

In my own country, Canada, COVID-19 already has taken the lives of more than 400 people. Many more would be dead if we were not engaged in social isolation and other important public-health measures. That is tragic, but it is important to put such numbers in perspective. A century ago, the so-called Spanish flu (a misnomer) killed about 55,000 Canadians—this at a time when the country’s population was a quarter what it is now.

Yet today’s media reports often echo that description from the early AIDS era: “daily roll calls of the dead [and] first-person accounts of the agony of dying.” Even policymakers sometimes risk descending into unhelpful overreaction—with governments now closing outdoor parks, for instance, an arguably counterproductive move that will relegate people to more densely packed indoor areas. More broadly, as the New York Times recently noted, “leaders across the globe are invoking executive powers and seizing virtually dictatorial authority with scant resistance.”

We should remember that when it came to AIDS, it wasn’t primarily heavy-handed government policy that changed the way citizens behave in the long run, but the decisions of ordinary people. Nor should we forget that during the AIDS crisis, there were efforts to inflict shame on a whole community—especially those members of the community who weren’t behaving in the sanctioned manner.

One sees parallels to that now, with social media being used as a weapon to mob people who leave their homes without a hall pass. I can attest that the negative effects of these campaigns persist long after the initial disease outbreak is over.