Top Stories

“Amazon Empire” Struggles Under Its Own Contradictions

Like all Frontline documentaries, Amazon Empire, a yearlong effort with 57 on-record interviews, is a stellar investigation of labor malpractice, antitrust issues, and the growing privacy and data security concerns over Amazon’s Alexa and Ring products.

Editor’s note: Quillette receives a small amount of revenue from Amazon affiliate advertising.

A review of Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos, Frontline, PBS, February 19, 2020.

William Lee, an English clergyman of Calverton, may have started the industrial revolution when he invented a stocking frame in 1589. Its basic principle is still used in manufacturing textiles. But when Lee first applied for a patent, Queen Elizabeth I refused: Her Majesty thought it would end hand-knitting and destroy jobs.

By the late 19th century, the United States surpassed Great Britain as the world’s largest economy, fueled in part by John D. Rockefeller’s innovations in energy production. But despite cost benefits to consumers, the Justice Department brought an anti-trust suit against Standard Oil and splintered the company in 1911.

Meanwhile, catastrophic train wrecks crippled the movement of goods and people: there was no safe way to stop bigger and faster locomotives. Not until the son of a New York machine shop owner, George Westinghouse Jr, came up with the airbrake. Predictably, the freight lines balked: at $1.50 a day, it was cheaper to employ Irish immigrants—“brakemen” who ran from car to car and manually applied the brakes directly to the wheels. They rode on top of trains in all hours, in all weather conditions. Next to coal mining, it was the most dangerous job. The government would eventually step in: the Westinghouse airbrake became the standard—but only after 5,000 brakemen were killed or maimed in a single year.

In the century to come, from A&P to Microsoft to Walmart, the arc of bold commercial innovation, resistance to innovation and its eventual acceptance, at various human costs, traces the narrative of our present sanctum sanctorum of global commerce. Is Amazon a “huge and unstoppable force,” as its first employee Shel Kaphan claims? Is Jeff Bezos, now the richest man in the world, a modern day robber baron? Or is it merely progress rebranded, a new expression of capitalism in the hyper-digital age?

As it braids the stories of the man and his company into a riveting two-hour blitz of exclusive interviews, Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos, a new PBS Frontline film, strains for moral clarity in an age-old conflict between fairness and free trade.

“Simply because the company’s been successful doesn’t mean it’s somehow too big.” – Amazon Web Services CEO Andy Jassy. FRONTLINE examines the debate over Amazon’s power, impact and the cost of its convenience. TONIGHT at 9/8c: https://t.co/W4aK11tCa5 pic.twitter.com/Swd3boxvx8

— FRONTLINE (@frontlinepbs) February 18, 2020

Amazon’s influence and Jeff Bezos’s personal wealth have triggered investigative reports, harrowing delivery driver accounts and condemnations by Democratic lawmakers and presidential candidates who often call out Bezos by name. But no speeches or ink marks can match the stark intimacy of a stylized audio-visual showcase: Amazon Empire forces us to look into the eyes of burnt out warehouse workers as they recount their toils; to experience the hot-seat discomfort of Amazon executives, to ponder their timorous ticks and gestures.

The film reveals that life at Amazon fulfillment centers is a far cry from Westinghouse’s magnanimous offerings of housing and hospitals for his nineteenth century factory laborers. Packaging can be grueling, repetitive work—product flow is relentless, tough quotas are set, then increased. The scale is different as well: Amazon employs 600,000 workers with centers in every state.

“They’re safe; we pay double the minimum wage, the national minimum wage; we have terrific benefits,” said Jeff Wilke, Amazon’s CEO of Worldwide Consumer. “The benefits for the folks that work on the floor are the same benefits that my family has access to. Our family leave is like 20 weeks.”

But the film points to a patchy safety record, for products and workers. Shoddy motorcycle helmets sold on Amazon.com caused injuries; a defective dog collar snapped, striking and blinding a woman. And then there are the fulfillment center employees, many of whom have had to work in excessive heat, without proper air conditioning.

“We’re not treated as human beings, we’re not even treated as robots,” one former warehouse employee recounts. “We’re treated as part of the data stream.”

Like all Frontline documentaries, Amazon Empire, a yearlong effort with 57 on-record interviews, is a stellar investigation of labor malpractice, antitrust issues, and the growing privacy and data security concerns over Amazon’s Alexa and Ring products. But it is also a curated experience—a critical exposé of a monopolistic behemoth whose appeals to economic wisdom are treated as the devil’s due.

“We are not the biggest retailer in the United States,” explains former Obama press secretary Jay Carney, now top spokesman for Amazon. “In fact, the biggest retailer is two and a half times our size. Walmart’s much bigger than we are and has been forever… We’re less than one percent of retail globally.”

The problem with this section of Carney’s interview is that it never makes it into the feature film that aired on PBS. Frontline cut it for the online extras.

The film also leaves out geopolitical dynamics with China, the largest exporter of goods sold by Walmart, and now Amazon. In fact, the rise of all modern super-retailers can be traced to a single iconic image: Deng Xiaoping putting on a cowboy hat at a Houston rodeo in 1979. Arguably the most momentous event in post-industrial history, it marked China’s pivot from the Soviet model to the largest economic engine: the U.S. consumer market. But unlike another Frontline film, Is Walmart Good for America?, first aired in 2004, Amazon Empire elides 40 years of globalization and manufacturing transfer to the Chinese factories.

Instead, the film fixes on Jeff Bezos himself. The Amazon founder did not grant Frontline an interview. But the filmmakers did stitch a generation worth of images and footage, including, oddly enough, a montage of what James Marcus, ex-Amazon editor, described as Bezos’s “large eruptive laugh.”

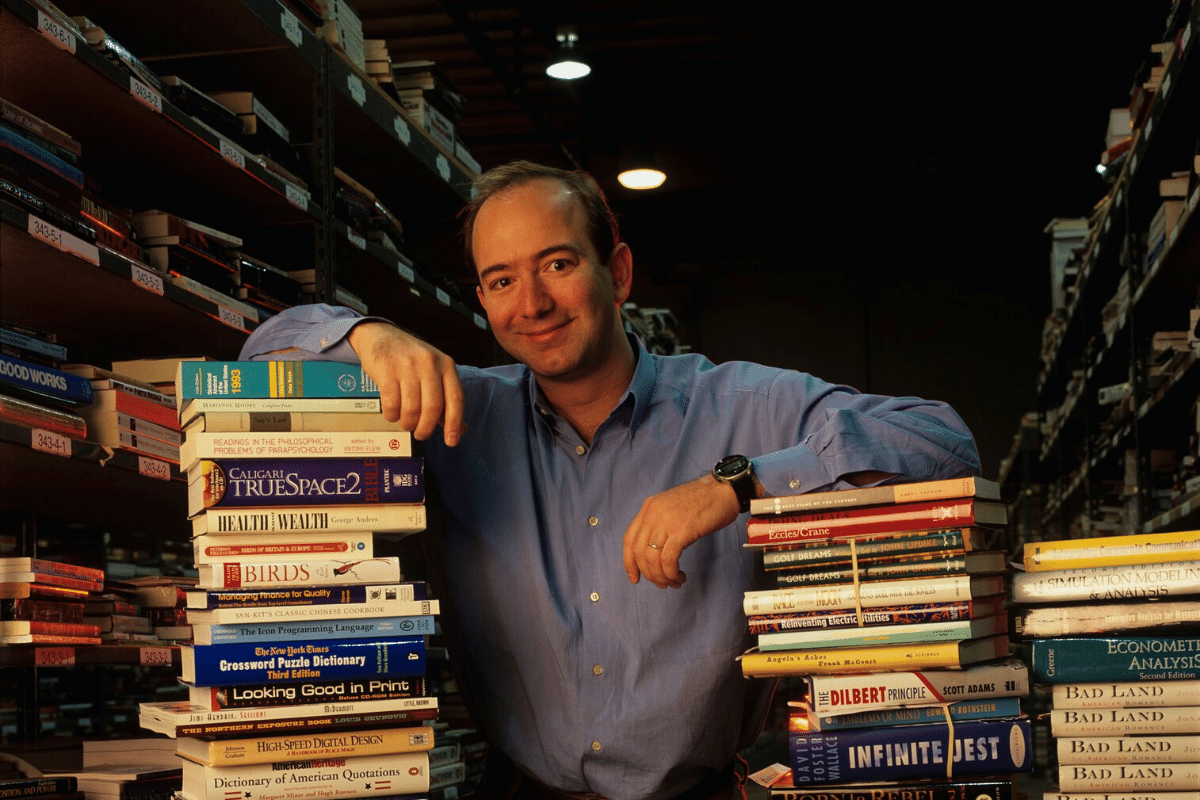

“Jeff was not a figure out of folklore,” Marcus said about Bezos’s goofy awkwardness at the time when Amazon became the Internet’s first book shop.

“I picked books as the first best product to sell online,” Bezos, still sandy-haired and doughy, explains in a shaky piece of ’90s footage. “Because books are incredibly unusual in one respect. And that is that there are more items in a book category than there are items in any other category by far. You could build a store online that couldn’t exist in any other way.”

From then on, the film charts his promethean transformation—from a happy-go-lucky tech nerd, cranium wobbling over a jolly torso, to a Lex Luthor-like titan, muscle-clad and severe, with $110.5 billion net worth and galactic ambitions.

The first online bookshop he and his former wife, novelist MacKenzie Bezos, started in a small Seattle house would come to dominate the print and eBook market, bullying publishers into aggressive bottom-dollar pricing. One anecdotal account by a former product manager Randy Miller referred to a “cheetahs and gazelles” strategy: going after the smaller, weaker publishers so as to intimidate the larger ones.

Amazon Vice President Jennifer Cast, the company’s 25th employee who helped build its book business, denied any knowledge of the cheetah-gazelle ploy. Asked why most book publishers would not speak on camera, Cast said: “I don’t know why they wouldn’t speak their minds. We certainly value speaking our minds.”

One publisher who did speak his mind was Denis Johnson, a poet-turned-publisher of the left-leaning Melville House Books. When Amazon removed “buy” buttons from his titles, Johnson made national news for refusing to give into the company’s pricing terms.

“That’s an old Walmart trick,” said Randy Miller, referring to Walmart supplier rooms where vendors are pushed to lower prices, often at substantial loss. “It’s not like Amazon created that.”

“We were just this little mom and pop publishing company, publishing poetry books and translated fiction,” said Johnson, exquisitely urbane and measured, comparing his plight with Amazon to that of Jesus in the Gospel of Mathew, Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s.

“I am not complaining that Amazon is selling our books,” he explained. “I am just complaining of the way their tactics are hurting the industry I love.”

What complicates this David vs Goliath episode is that Johnson is in fact a motivated ideologue—a martyr in the cause of books, but only those that agree with his political sensibilities. In 2018, he took to Twitter to publicly denounce literary agent David Vigilano for representing Donald Trump Jr’s book manuscript. At the time, I asked Mr. Johnson if he considered that a book written by a president’s son might reveal something in the public interest.

“It’s called normalizing a fascist,” Johnson shot back. “You’re with them or against them. Vigilano is clearly with them, and so are you.”

Amazon’s self-publishing option cannot replace traditional presses like Melville House for lesser known or beginning authors who count on cash advances to live on between books. It can, however, provide an alternative platform for writers of controversial works, dropped or cancelled for political reasons, serving as a backstop against losing readers.

War correspondent Hesh Kestin is an American-Israeli David Ignatius of sorts. After decades of reporting on terrorism, arms trade, and intelligence from Europe and the Middle East, he turned to fiction. His latest novel, The Siege of Tel Aviv, a techno-thriller a la Tom Clancy first published by Dzanc Books, imagines Israel losing its first battle when five Arab armies invade it in a joint assault. “Scarier than anything Stephen King ever wrote—and then the fun begins, as Israel fights back!” reads the blurb on the front cover written by Stephen King himself.

The Siege of Tel Aviv was not the first Kestin book published by Dzanc. But after a dozen tweets calling his novel Islamophobic, the indie publisher pulled the novel and publicly apologized for it. So Kestin took Dzanc’s ebook to Amazon along with an identical printed version. He also made the first 50 pages of the novel available for free.

Amazon offers no distribution channels to bookstores—it’s hard to connect with fans—and Kestin admits that the novel’s ‘cancelation’ had added slightly to its caché. But without Amazon, he would be out of business as an author.

“Though Amazon is often condemned for decimating brick-and-mortar bookstores, it also permits writers to get around the limitations of an industry stuck in the 20th century, if not the 19th” he tells me. “We’re left with the one point of sale, which thankfully is a good one. Sales are slow but steady. Amazon is 21st century American samizdat.”

The final chapter of the film takes us to Long Island City, Queens, the site of Amazon’s would-be HQ2 which the company abruptly abandoned amid protests. The David vs Goliath story is recapitulated: an anti-union tech giant waving off tax blandishments from major cities to seize on a $3.5 billion plunder from working New Yorkers. Scenes flash by in a rapid tableau: “You are in a union city!” Council Speaker Corey Johnson roars atop a finance committee hearing while Amazon executives squirm in their seats. New York City mayor, Bill de Blasio, once the principle cheerleader of the deal, waxes indignant about the arrogance of a billionaire who thinks he can just walk into his town and call the shots.

In fact, the $3 billion in tax breaks, with an additional $500 million in capital grants for building construction, were not ‘free money’ to Amazon: the relief was a partial rebate on future taxes. And while Amazon did not agree to allow its own employees to unionize, the cash for the office buildings was to offset the extra cost of employing union construction workers.

What’s more, Amazon’s pullout from Queens, lamented by the majority of New Yorkers, wasn’t caused by spontaneous grassroots protests. It was a well-organized political campaign first started as a series of tweets by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (who doesn’t represent the would-be HQ2 site). Moved by the socialist winds of her upset over the establishment Democrat Joseph Crowley, a group of progressive lawmakers lined up in opposition to the company and against the economic interests of their constituents.

Unsurprisingly, the purge of Amazon, along with the 25,000 jobs it promised, prompted a backlash in the months to come, including a primary challenge to Rep. Ocasio-Cortez from a CNBC journalist and author Michelle Caruso-Cabrera.

“Contrary to what newcomers may believe, gentrification and congestion weren’t always the city’s biggest problems,” wrote New York architect and professor Vishaan Chakrabarti in his op-ed Losing Amazon Is The Biggest Unforced Error In NYC’s Economic History. “Another major downturn will hit New York one day. And when it does, Amazon being run out of town might be remembered as a harbinger of what was to come.”

Which is to say that history is not inevitable, not even in retrospect. By evading politics and global markets, the film is locked into a circular critique—it points to Bezos to explain Amazon and to Amazon to make sense of Bezos. It tells the story of a globular monopoly while papering over the competition: Walmart, Target, Wayfair and Ali Baba, China’s challenge to Amazon’s purported dominance. There is Jeff Bezos, the ascetic profit seeker. And then there is Jeff Bezos, the savior of the Washington Post, a hands-off publisher commended by most of the paper’s staff. He is the billionaire among billionaires, but not a débauchée. He is mocked for frivolously spending on rockets and drones while the global threat of human-transmitted pathogens is recasting our views on automation, from job-killing robots to potentially lifesaving technology.

The film finds itself bogged in these contradictions, which perfectly reflect the moral confusion of American consumers: The vast fortunes of Amazon are amassed not by the exploitation of indie publishers or voyeuristic police departments, but by the urban gentry who shop at its subsidiary Whole Foods, watch streaming Amazon shows, and enjoy free 2-day home delivery despite its carbon footprint. None want to live in a world without Amazon Prime, without its instant consumerist bliss, even as they heroically denounce Jeff Bezos on social media under the socialist banner.

No documentary can untangle this tricky neoliberal dilemma without bumping into its own aesthetic limitations, and this one is no different. Empire or not, no gathering of resources and people on Amazon’s scale can function as a plaything of one man’s reckless ennui—even if that man is the richest man in history. A story to encompass an entity so imponderably vast calls for a more generous form-factor. Maybe it’s time for Jeff Bezos, a man who founded the first Internet bookstore, to write a book.