COVID-19

Humanity's Greatest Foe: Pandemics Through the Ages

The blind struggle against infectious diseases began to end when the microscope allowed for the discovery of the bacilli responsible for anthrax, tuberculosis, and cholera in the late 19th century.

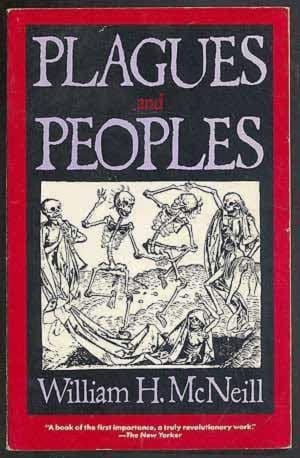

A review of Plagues and Peoples by William McNeill, Anchor, 365 pages (1998)

Readers seeking a longer historical perspective on the coronavirus pandemic would do well to consider William H. McNeill’s brilliant book, Plagues and Peoples. Originally published in 1976, Plagues and Peoples shows, in less than 300 pages (not including the appendix, notes and index), “how varying patterns of disease circulation have affected human affairs in ancient and modern times.” Not everyone, understandably, will wish to dwell upon the endless series of calamities infectious diseases have exacted in our collective past. The uncertain, terrifying ordeal immediately before us is quite enough. But along with well-informed worry, McNeill’s masterful account induces both awe and hope at our species’ capacity to endure the worst from its most ancient adversaries.

To adapt words McNeill wrote in a slightly different context: The history of mankind’s long struggle against infectious diseases “will not solve contemporary dilemmas. It may, nonetheless, provide perspective and, as is the wont of historical awareness, make simple solutions and radical despair both seem less compelling. Muddling through in the face of imminent disaster was the fate of all past generations. Perhaps we will do the same, and others after us. Moreover, since we must still make decisions every day, it probably helps to know a little more about how we got into our present awesome dilemma… Even if that turns out to be false, there remains the pale, cerebral, but nonetheless real delight of knowing something about how things were different once, and then swiftly got to be the way they are.”

McNeill begins more than 100,000 years ago, when man was not yet man, but rather another animal living in an ecological system over which he had no conscious control. Man himself appeared when he first flung open the gates of cultural evolution. Similar to but much swifter than its biological counterpart, cultural evolution endowed its beneficiaries with an ever-expanding dominion over the natural world. But human ingenuity could not touch what it could not see. And so invisible microbes alone remained as a terrible biological menace to humanity.

The long history of human progress involved almost no discernable advancements against infectious diseases until quite recently. Like death itself, that fact is quite striking as soon as one pauses to notice it. Our remotest ancestors, naked, inarticulate and ignorant, were less vulnerable to these invisible predators than our great-grandparents were. Every major advancement in humanity’s control over nature only increased our blind exposure to deadly microbes by increasing the size and density of the populations on which they feed and by widening and accelerating the networks on which they travel.

In this respect alone, biological adaption remained far more important throughout almost all of human history than cultural adaptation. New and murderous diseases arrived at frequent intervals, burned through established communities with terrible ferocity, and the affected population collapsed until either the disease disappeared or became endemic in a sustainable equilibrium between host and parasite. There is a natural pattern of convergence between microbes and host communities as the least fatal strains of the disease and those least susceptible to it are the most likely to survive.

Irrigation farming was the first technological breakthrough that created food surpluses capable of sustaining large settled communities, including densely populated cities. In changing the natural landscape to make it fit for agriculture, farmers unwittingly opened the door to hyper-infestations of all kinds. Farmers proved adept at combating visible pests like mice and weeds, but against microbes they struggled blindly and helplessly. McNeill speculates that the prevalence of infectious diseases contributed to the authoritarian practices of governments in societies dependent on irrigation agriculture. “The plagues of Egypt,” he writes, “may have been connected with the power of the Pharaoh in ways the ancient Hebrews never thought of and modern historians have never considered.” Americans who have accepted orders to stay home without even whispering about the right of assembly enshrined in the Constitution are sure to see that he has a point. Several governments are now using cell phones to track citizens’ every movement to monitor possible contagion patterns. It would have taken much more than the parting of the Red Sea for Moses to escape from that.

Hunter-gatherer societies typically observed practices that kept birthrates low. But the prevalence of infectious diseases among agricultural societies meant that none could hope to survive without birthrates well above replacement level. Cities were always deadly, and every one of them, from 5,000 years ago until about 120 years ago, depended on constant replenishment from more healthy hinterlands in order to sustain themselves. The demographic results were highly unstable, as population centers expanded drastically and collapsed in recurring cycles.

Surplus populations fueled not only cities but armies. And civilized communities were constantly beset by two grave menaces, infectious diseases and other human beings organized and armed for pillage and plunder—or as McNeill styles it, “microparasitism” and “macroparasitism.” There is a striking analogy between these two great scourges of agricultural societies. A community’s first contact with micro- and macro-parasites is likely to be catastrophic. But neither warlords nor pathogens are able to flourish for long by destroying subject populations. And so gradually an equilibrium emerged as endemic diseases and extractive empires entrenched themselves as tolerable nuisances.

Around 500 B.C., McNeill speculates, the oldest population centers in Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley began to stabilize, at least 3,000 years after the introduction of irrigation farming. Trade patterns brought the entire region within a common disease pool while the administrative empires of the Near East reached the furthest limits when the Persians failed to conquer Greece, and then Alexander, having conquered Persia, failed to conquer India. At the same time, the populations of the western Mediterranean, Ganges Valley (India) and Yellow River Valley (China) entered a period of dramatic expansion. Incidentally, the founders of the philosophical systems characterizing all three civilizations outside Mesopotamia lived around the same time as well—Socrates (470 — 399 B.C.), Buddha (553 — 483 B.C.), and Confucius (551 — 479 B.C.).

Contact between the four major civilization centers was sporadic or nonexistent until the Christian era. Each constituted its own distinct disease pool, sustaining endemic infections that could be catastrophically lethal whenever they swept into populations without prior exposure. The population of the Roman Empire at the time of Augustus’s death was 54 million, roughly equal to the 59.5 million recorded in an imperial census of Han China around the same time. Regular trade routes connecting the major civilizations first emerged along what Romans called the Silk Road, named after the primary commodity carried westward from China through Persia and then into Western Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. The same route brought with it new and terrible diseases, causing a demographic collapse in Western Europe from which it did not recover for nearly a millennium.

The spread of the coronavirus is rather striking in light of this ancient pattern: First China, then Iran (i.e. Persia), then Northern Italy and then everywhere else. Trade routes do not explain this strange coincidence. It is an additional reminder, if one were needed, that we have not yet tamed or contained the microscopic predators in our labs as we have the lions and tigers and bears in our zoos.

Not all disease pools are created equal. When isolated populations begin to converge, some inevitably give much more than they get. Western Europe suffered the most, though hardly alone, in the first great confluence of civilized disease pools.

The first truly catastrophic plague that swept the Roman Empire arrived in A.D. 165, a year before the first Roman ambassadors arrived at the Han court, killing between a quarter and a third of all affected populations. Another epidemic of equal severity arrived in A.D. 251 causing 5,000 deaths a day in Rome alone at its peak. Christianity benefited immensely, and not just for the consolation of hope it offered in a better world to come. Christian teaching emphasized the duty of caring for the sick, while faith in an everlasting life steeled caregivers to brave diseases that sent Pagans fleeing in terror. As other political institutions providing services broke down, the influence of the Church filled the void.

The bubonic plague first arrived in Europe in A.D. 542. And available evidence suggests that the plague epidemics that swept the Mediterranean in the sixth and seventh centuries were every bit as destructive as the more famous Black Death of the 14th century, though only in the latter case did the dreaded black rats infest Northern Europe as well. Indeed the Black Death is unique only as the most memorable pandemic that swept through Europe. While earlier epidemics had ravaged Roman civilization as it collapsed into darkness and chaos, the plague that arrived in Europe in 1347 only briefly, if spectacularly, interrupted an era of immense population growth. This, and not its destructive power alone, accounts for its singular place in the collective memory of the West.

Other diseases that had originally burned through Europe with catastrophic results, such as measles and smallpox, had become endemic as childhood diseases by the 10th century. As a result, Europeans had much more to give than receive as they encountered heretofore isolated populations, most notably the crowded civilizations of the New World.

An invisible army of smallpox germs was primarily responsible for Cortez’s and Pizarro’s conquests of Mexico and Peru. Along with the mass death inflicted, the psychological influence on the living was perhaps even more significant. Both the Spanish and the Native Americans interpreted the epidemics as signs of divine favor or disfavor. And the results were not remotely ambiguous. One side was invincible and the other utterly helpless. And so armies numbering only in the hundreds, backed by what they and their enemies quickly assumed was the hand of an omnipotent God, secured control over a vast empire inhabited by millions. The world has never seen a more lopsided conquest, or a more lopsided convergence of disease pools. Other Eurasian diseases followed the initial outbreak of smallpox. The scale of the catastrophe for Native American populations is hard to imagine—from the pre-Columbian peak the population likely dropped by a ratio of 20:1 or 25:1.

Horrible as it was, the catastrophe of the New World was also the last of the great calamities in the process that brought the world’s population into one common disease pool. European expansion knit the entire world into one vast network of exchange. By 1700 or thereabouts, global trade networks had become so regular that no diseases endemic in one major population center could suddenly thrust itself catastrophically into another. Mankind has good reason to fear exposure to foreign peoples. But prolonged isolation is incomparably worse.

One group, however, remained uniquely vulnerable to the lethal power of infectious diseases—newborns and young children. That had always been true of endemic diseases. But as trade and disease networks became more regular and pervasive, they drastically reduced the number of people who lived to adulthood without being exposed. Diseases that had once ravaged communities indiscriminately now focused almost all their ferocity on children. The psychological toll must have been immense. Cultures adapted to a degree, but grieving parents suffered just as acutely as they always had and always will. However, the demographic toll was much less severe, for young children are more easily replaced than adults. As a result, the world’s population began to expand rapidly around 1700.

* * *

And yet, to repeat an earlier point, the brilliant cultural innovations that established the first era of globalization did virtually nothing to tame the destructive power of infectious diseases. Ordinary animal biology, not our extraordinary brains, was decisive.

To be sure, successful cultural adaptions to diseases occasionally did occur, usually explained and understood in religious terms. Deuteronomy 14:8, for example, sternly enjoins readers not to eat bats. But as we now know, such localized cultural adjustments could not protect those who adopted them from neighbors who didn’t. The most ingenious folk adaption to disease was the smallpox inoculation, which was practiced in various customary forms in Arabia, North Africa, Persia, India, and China before Europeans adopted and began to systematize the practice in the 18th century.

Only then, in the 18th century, did medical science, as opposed to custom reinforced by ritual and religion, begin to make definite progress in the ancient struggle against infectious diseases. But at first these advantages were mixed, as the medical profession unleashed itself from the ancient maxim, “first, do no harm,” and lunged with the arrogance of a pioneer into the unknown. In 1799, America’s best doctors treated George Washington’s throat infection by draining 3.75 liters of blood from his body. When the journalist William Cobbett suggested this practice had killed the first president, he was chased out of the country by a libel suit. In 1832, the president of the New York State Medical Society suggested, as a treatment for diarrhea caused by cholera, plugging the rectum with beeswax or oilcloth. Other doctors recommended tobacco smoke enemas. Anyone familiar with the early history of medicine can only marvel at its hubris, pity its victims, and sigh in gratitude at its gradual and ever more astonishing successes.

Improvements in material and economic conditions were far more important at first in combating disease, but these were easily reversed by an epidemiological version of the Malthusian trap. Nineteenth century tenement buildings were as overcrowded and filthy as anything seen in Roman times. Occasionally, even significant advances in hygiene among affluent classes backfired by delaying exposure to diseases that were far less dangerous to children, as was the case with Polio.

With steamships and railroads came new diseases that had never before been able to travel. Cholera, long endemic in Bengal, spread throughout the world in the middle decades of the 19th century. And in 1918, the Spanish flu went around the word like lightning, killing at least 20 million in just over a year. Medical systems were quickly overwhelmed and broke down. But the very rapidity of its spread meant that its acute phase was brief, “so that within a few weeks human routines resumed and the epidemic faded swiftly away,” McNeill writes. Influenza had been around for a long time. An epidemic in 1556 — 1560 killed off as much as 20 percent of England’s population, according to one scholarly estimate, while that of 1918 did not reach one percent. And yet the 1918 pandemic introduced a new dilemma for a more densely populated, more tightly interconnected world to contemplate, namely, how far should a society intervene to contain a highly infectious disease that combines a low fatality rate with a staggeringly high number of potential total deaths? Over the next 100 years, however, very few people bothered to ponder this grave question.

The blind struggle against infectious diseases began to end when the microscope allowed for the discovery of the bacilli responsible for anthrax, tuberculosis, and cholera in the late 19th century. Finally, mankind could see its ancient enemy. And the same cultural ingenuity that has marked our species from the beginning began to work relentlessly upon those that had hunted us in the darkness.

World War Two was the first major conflict in modern history in which soldiers’ weapons proved more deadly than the diseases they carried. In the second half of the 20th century, as scientists built rockets that could leave Earth and bombs that could blow it up, medical experts also began efforts to rid our ancestral home of its most irksome microscopic inhabitants. In 1977, just eight years after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, the World Health Organization succeeded in eliminating smallpox. Possibilities only imaginable to maniacs and prophets had come finally into our grasp.

In 1976, when McNeill first published his great book, he warned that our advantages may be temporary. “The race between skills and ills was… by no means decisively won—or lost; and in the nature of ecological relationships is never likely to be.” The technological advancements that came to fruition in the 20th century were as dramatic and unprecedented as those of 5,000 years earlier, when irrigation agriculture began a new stage in mankind’s place in the world that was also the beginning of recorded history. As that immense advance in man’s power over nature opened the door to new and formidable counter-attacks, so might the great strides we’ve made since the Enlightenment. The point is not that we are doomed to retreat, or even stand still. Only religion can offer the promise of a future Eden of repose. As I write, billions of citizens in the world’s wealthiest, most technologically sophisticated societies are huddled up in their homes, like a primitive village in the shadow of a man-eating panther.

There is inspiration as well as wisdom in recalling the ancient chain of progress that still binds us to our ancestral past. Every single inch is marked by calamity. We will endure only as our ancestors endured, bravely and stubbornly, matching our wits against the infinite whims of a hostile world.

Adam Rowe is a postdoctoral teaching fellow at the University of Chicago. A historian of the United States, Rowe’s research has focused on American political thought from the Revolution to the Civil War. He can be found on Twitter at @adamrowe82