Top Stories

That Elusive Feeling We Call Love

Love is irrational, intense and all-consuming—and we dream of being loved in return.

Every writer worth reading—from the good to the great to the canonical—has, at some point or other, explored the subject of love. Yet, despite some striking insights and equally striking metaphors, none of these writers has been able to answer the question of what love is. I don’t think anyone knows. I certainly don’t. But I know what love isn’t.

Getting along is not love. Being married is not love. Being married for 30 years is still not love. Raising three kids together is not love. Having common interests is not love. Warmth, affection, and tenderness are not love (praiseworthy as they are). Duty and loyalty are not love. Sexual desire is not love (although, in this line-up, it is the only essential component). All of the above combined is not love. All of the above combined and raised to the power of 10 is still not love. It’s a relationship. A good relationship, solid relationship, long-term relationship. But still a relationship. And although the difference between love and a relationship is not in degree, but in kind, we tend to use these words interchangeably. Perhaps because a relationship is all that most of us will ever experience. (More on this in a moment.)

Love is good at its own PR. Every time the word is uttered, it brings to mind a powerful and ennobling force that lifts us up and makes us kinder, braver, and generally worthier versions of ourselves. But, as Huckleberry Finn would have said, it ain’t so. Romantic love is profoundly selfish. When we love, we want something in return: to be loved back. As long as this goal is achievable, and consistent progress towards it is made, love is indeed fantastic. But if the goal remains unattainable, if our pleas are left unanswered, if the target doesn’t budge or—worse, much worse—budges in the direction of someone else, love becomes a dangerous force. It breaks us and it distorts us and it compels us to destroy.

Forget about levitating into the clouds. Instead, we sink into jealousy and obsession. Our self-control weakens, our consciousness splits, we oscillate between affection and disdain, contempt and adulation, an instinct for forgiveness and an urge to avenge. Love changes us, for sure—but not for the better. It can transform a decent man into a stalker, a sound man into a petulant hysteric, an honest man into a snoop, a cultured man into a boor, a kind man into a sadist. (Needless to say, all of this equally applies to women.) Romeo falls in love and, overnight, becomes moody and sombre and generally bad company, staggering about Verona, mumbling: “Love is a smoke made with the fume of sighs.” On the brief occasion that he regains his former spark, Mercutio is quick to comment: “Why, is not this better now than groaning for love? Now art thou sociable, now art thou Romeo.” (Translation: “For God’s sake, man, pull yourself together, we can’t take this any more.”) Over the next three days, Romeo kills two people, causes the death of two more, and finally tops himself. Ain’t love grand?

If only Romeo had waited. How different might things have been: no bloodbath, no dead friends, no double suicide. Instead, the star-crossed lover would have gone back to his carefree life, and drinking and pranks and debauchery; and Romeo and Juliet would have entered school curriculum as a light comedy. Because sexual love doesn’t last. And before you tell me that this is simply a reflection of my emotional deficiencies, here is what Shakespeare had to say:

There lives within the very flame of love

A kind of wick or snuff that will abate it.

This is Hamlet’s Claudius instructing us on the ways of the world. “Flame” is an enduring metaphor for love. I would even call it lazy, were it not so accurate. The flame of love is lit by novelty and nourished by mystery. It gutters with habit and dies with saturation. Romeo, the golden boy, young and rich and spoiled! His life is charmed, he has no care in the world—and so all the time for dreams, longings, and fantasies. How well I know his type: impulsive, exalted, he feels so strongly, loves so deeply… forgets so quickly. Six months is all I’d give him. Six months of waking up and seeing Juliet, and going to bed and seeing Juliet, and coming home and seeing Juliet, and leaving the house and hearing Juliet from the balcony: “Art thou gone so, love, lord, ay, husband, friend! I must hear from thee every day in the hour.” Soon, Romeo will develop tics and twitches and will tremble at a mere mention of his wife’s name. He will start bunking at Mercutio’s. Perhaps he’ll get a bachelor pad. He may even hook up with his former flame Rosaline. Either way, his love will go as quickly as it came.

Sexual desire is powered by imagination. The stronger the imagination, the stronger the elation of early love. And the harder the disappointment. “Her name is Dulcinea, her country El Toboso, her rank must be at least that of a princess, since she is my queen and lady, and her beauty superhuman…” So speaks Don Quixote of the fair maiden in whose name he would soon commit countless acts of heroism. In reality, Dulcinea is called Aldonza Lorenzo. She is a local peasant woman who breeds pigs and entertains gentlemen of El Toboso for money. If Don Quixote knew this, what would he do?

Who knows? Perhaps he would act sensibly. Perhaps he would give it a serious thought, then decide that he is not getting any younger, that the life of chivalrous adventures is taking its toll, and that the time is right to settle down. He would consult his loyal squire Sancho Panza. “You are no oil painting,” Sancho might posit, “so you don’t really have much choice. Aldonza is a good woman, she is shrewd and practical and skilled around the house. She will make you fresh gazpacho, she will feed and clean Rocinante, and—although this is of no importance to a gallant knight—she must be quite good in bed.” So Don Quixote would renounce love and begin a relationship. It never comes to that, of course, as the world’s most famous idealist dies without ever meeting Dulcinea, and the image of an exalted princess with superhuman beauty stays untainted in his heart. Some would say this is immature. I say it’s glorious.

I am writing from experience. I was in love, and I knew elation and despair. Unrequited love wrought havoc in my life when I failed economics finals. I tried to study, but the book stayed open on page two—“Introduction”—for three days and I never read past the sentence: “Economists use many types of data to measure the performance of an economy.” But love also made me better, gave me the courage to do things I had been afraid to do. Inspired by love—and after two years of planning, coming close, but pulling out at the last minute—I cleared out the garage. I started penning poetry, because the “eternal summer” of my subject, 19 at the time and a worthy rival to Fair Youth, deserved to be immortalised for future generations. His distinctive features were a Dragon Pro skateboard and a spectacular mane of hair that changed colour every week. These nouns rendered themselves best to trochaic tetrameter, so I tried to write like William Blake. I failed (I think).

But the best part of being in love was the thrill of the chase. That sensation, subtle yet unmistakable, like the early change of seasons, that the target is ceding, ceding, ceding more, until—oh, joy!—the fortress falls, the enemy capitulates, and your victory is final and complete. You triumph, your imagination runs riot, you dream of feverish nights, of paroxysms of pleasure. Cherish this time, because soon it will be over—and instead of trochaic tetrameter, you will be writing joint shopping lists.

What I just described is, of course, not love. Just as Romeo’s lustful neurosis is not love, or Don Quixote’s chivalrous adulation. Just as a relationship is not love. What this is instead is a range of emotions that—out of laziness or ignorance—we refer to as “love.” Love is something that most of us will never experience. I hasten to add that these are not my words—they are Simone de Beauvoir’s. “Real love is a great privilege,” Beauvoir wrote, “but it is also very rare.” And the reason that love is rare is because it is a talent. And, like any talent, it’s the domain of the few. These are also not my words, they are Ivan Turgenev’s, who tested all his protagonists through their ability to love. Hardly anyone passed the test.

“The only time in my life that I was in love was with my nanny when I was six years old.” So says one of Turgenev’s characters, a happily married middle-aged man. This short sentence offers the best explanation of love that I have ever seen. Love is irrational, intense and all-consuming—and we dream of being loved in return. But love—real love—also has no claims, no demands, and even if we know that our case is hopeless, we will always feel profoundly fortunate that this person had once been in our lives. This is how, I would imagine, a six-year old child feels about a grown-up, unattainable woman. And it is a great parable for love.

For Turgenev, love is sacrifice—but not the showy, impulsive sacrifice of Romeo. It is the clear-headed, quiet heroism of putting your comforts, needs, ambitions—and, if it comes to it, your life—on the line for another. I must add that love is when you continue loving someone long after they have stopped being what they once were. Twenty years ago, you might have married Rimbaud. Since then, he became senior brand manager. The most natural thing to do is to leave and look for another Rimbaud. Or maybe even Nietzsche. This is what I have done every time, and I have no regrets. But if you love, really love, you will still recognise in the pointless character on your sofa the glorious youth who once burned and raged and threatened the world with his dreams. And you will stay with him for love—not for pity, or duty, or because it’s the right thing to do. And this, of course, is talent.

It is also where love comes very close to another emotion. Friendship. It is my profound belief that friendship is a nobler feeling than love. Love fizzles out. Friendship—real friendship, not the friendship of shared hobbies—endures. Friendship is light. Love is heavy. When I read “Enter Mercutio,” I perk up, move closer to the page. I know it will be good. When I read “Enter Juliet,” I brace myself for sighs and oaths and all manner of excess. Friendship is simple, it needs no affectation, no embellishment, no multiple exclamation marks. “So you came? How kind.” So says Don Carlos to his childhood friend Marquis de Posa, under circumstances too poignant to repeat (do read Schiller’s Don Carlos. This play is perfection.) Compare this to Juliet’s “O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo?” And, in what is one of the finest images in world literature, The Little Prince’s “Voilà…, c’est tout…” just before the snake bites him and he dies. This is all The Little Prince says to his friend Saint-Exupery. This is all you need to say to a friend.

And finally, friendship—unlike love—has no agenda. It is free. Lovers tend to stay in the same place. Friends’ paths diverge, and diverge widely: we grow up, we move countries, we pursue different passions, other people enter our lives. But, whatever happens, wherever I am, I know that my friend is there. And when I see him again—in a year, or five, or 10—we will pick up where we had left, and it will be easy. It will be easy because our tie is real, it is not based on fantasy, or fear, or desire—but on the unity of mind and spirit, unity that is selfless, and happy, and free. If, like me, you have a friend like this, you know it is the best feeling in the world.

Every writer worth reading—from the good to the great to the canonical—has, at some point or other, explored the subject of love. Yet, despite some striking insights and equally striking metaphors, none of these writers has been able to answer the question of what love is. I don’t think anyone knows. I certainly don’t. But I know what love isn’t.

Getting along is not love. Being married is not love. Being married for 30 years is still not love. Raising three kids together is not love. Having common interests is not love. Warmth, affection, and tenderness are not love (praiseworthy as they are). Duty and loyalty are not love. Sexual desire is not love (although, in this line-up, it is the only essential component). All of the above combined is not love. All of the above combined and raised to the power of 10 is still not love. It’s a relationship. A good relationship, solid relationship, long-term relationship. But still a relationship. And although the difference between love and a relationship is not in degree, but in kind, we tend to use these words interchangeably. Perhaps because a relationship is all that most of us will ever experience. (More on this in a moment.)

Love is good at its own PR. Every time the word is uttered, it brings to mind a powerful and ennobling force that lifts us up and makes us kinder, braver, and generally worthier versions of ourselves. But, as Huckleberry Finn would have said, it ain’t so. Romantic love is profoundly selfish. When we love, we want something in return: to be loved back. As long as this goal is achievable, and consistent progress towards it is made, love is indeed fantastic. But if the goal remains unattainable, if our pleas are left unanswered, if the target doesn’t budge or—worse, much worse—budges in the direction of someone else, love becomes a dangerous force. It breaks us and it distorts us and it compels us to destroy.

Forget about levitating into the clouds. Instead, we sink into jealousy and obsession. Our self-control weakens, our consciousness splits, we oscillate between affection and disdain, contempt and adulation, an instinct for forgiveness and an urge to avenge. Love changes us, for sure—but not for the better. It can transform a decent man into a stalker, a sound man into a petulant hysteric, an honest man into a snoop, a cultured man into a boor, a kind man into a sadist. (Needless to say, all of this equally applies to women.) Romeo falls in love and, overnight, becomes moody and sombre and generally bad company, staggering about Verona, mumbling: “Love is a smoke made with the fume of sighs.” On the brief occasion that he regains his former spark, Mercutio is quick to comment: “Why, is not this better now than groaning for love? Now art thou sociable, now art thou Romeo.” (Translation: “For God’s sake, man, pull yourself together, we can’t take this any more.”) Over the next three days, Romeo kills two people, causes the death of two more, and finally tops himself. Ain’t love grand?

If only Romeo had waited. How different might things have been: no bloodbath, no dead friends, no double suicide. Instead, the star-crossed lover would have gone back to his carefree life, and drinking and pranks and debauchery; and Romeo and Juliet would have entered school curriculum as a light comedy. Because sexual love doesn’t last. And before you tell me that this is simply a reflection of my emotional deficiencies, here is what Shakespeare had to say:

There lives within the very flame of love

A kind of wick or snuff that will abate it.

This is Hamlet’s Claudius instructing us on the ways of the world. “Flame” is an enduring metaphor for love. I would even call it lazy, were it not so accurate. The flame of love is lit by novelty and nourished by mystery. It gutters with habit and dies with saturation. Romeo, the golden boy, young and rich and spoiled! His life is charmed, he has no care in the world—and so all the time for dreams, longings, and fantasies. How well I know his type: impulsive, exalted, he feels so strongly, loves so deeply… forgets so quickly. Six months is all I’d give him. Six months of waking up and seeing Juliet, and going to bed and seeing Juliet, and coming home and seeing Juliet, and leaving the house and hearing Juliet from the balcony: “Art thou gone so, love, lord, ay, husband, friend! I must hear from thee every day in the hour.” Soon, Romeo will develop tics and twitches and will tremble at a mere mention of his wife’s name. He will start bunking at Mercutio’s. Perhaps he’ll get a bachelor pad. He may even hook up with his former flame Rosaline. Either way, his love will go as quickly as it came.

Sexual desire is powered by imagination. The stronger the imagination, the stronger the elation of early love. And the harder the disappointment. “Her name is Dulcinea, her country El Toboso, her rank must be at least that of a princess, since she is my queen and lady, and her beauty superhuman…” So speaks Don Quixote of the fair maiden in whose name he would soon commit countless acts of heroism. In reality, Dulcinea is called Aldonza Lorenzo. She is a local peasant woman who breeds pigs and entertains gentlemen of El Toboso for money. If Don Quixote knew this, what would he do?

Who knows? Perhaps he would act sensibly. Perhaps he would give it a serious thought, then decide that he is not getting any younger, that the life of chivalrous adventures is taking its toll, and that the time is right to settle down. He would consult his loyal squire Sancho Panza. “You are no oil painting,” Sancho might posit, “so you don’t really have much choice. Aldonza is a good woman, she is shrewd and practical and skilled around the house. She will make you fresh gazpacho, she will feed and clean Rocinante, and—although this is of no importance to a gallant knight—she must be quite good in bed.” So Don Quixote would renounce love and begin a relationship. It never comes to that, of course, as the world’s most famous idealist dies without ever meeting Dulcinea, and the image of an exalted princess with superhuman beauty stays untainted in his heart. Some would say this is immature. I say it’s glorious.

I am writing from experience. I was in love, and I knew elation and despair. Unrequited love wrought havoc in my life when I failed economics finals. I tried to study, but the book stayed open on page two—“Introduction”—for three days and I never read past the sentence: “Economists use many types of data to measure the performance of an economy.” But love also made me better, gave me the courage to do things I had been afraid to do. Inspired by love—and after two years of planning, coming close, but pulling out at the last minute—I cleared out the garage. I started penning poetry, because the “eternal summer” of my subject, 19 at the time and a worthy rival to Fair Youth, deserved to be immortalised for future generations. His distinctive features were a Dragon Pro skateboard and a spectacular mane of hair that changed colour every week. These nouns rendered themselves best to trochaic tetrameter, so I tried to write like William Blake. I failed (I think).

But the best part of being in love was the thrill of the chase. That sensation, subtle yet unmistakable, like the early change of seasons, that the target is ceding, ceding, ceding more, until—oh, joy!—the fortress falls, the enemy capitulates, and your victory is final and complete. You triumph, your imagination runs riot, you dream of feverish nights, of paroxysms of pleasure. Cherish this time, because soon it will be over—and instead of trochaic tetrameter, you will be writing joint shopping lists.

What I just described is, of course, not love. Just as Romeo’s lustful neurosis is not love, or Don Quixote’s chivalrous adulation. Just as a relationship is not love. What this is instead is a range of emotions that—out of laziness or ignorance—we refer to as “love.” Love is something that most of us will never experience. I hasten to add that these are not my words—they are Simone de Beauvoir’s. “Real love is a great privilege,” Beauvoir wrote, “but it is also very rare.” And the reason that love is rare is because it is a talent. And, like any talent, it’s the domain of the few. These are also not my words, they are Ivan Turgenev’s, who tested all his protagonists through their ability to love. Hardly anyone passed the test.

“The only time in my life that I was in love was with my nanny when I was six years old.” So says one of Turgenev’s characters, a happily married middle-aged man. This short sentence offers the best explanation of love that I have ever seen. Love is irrational, intense and all-consuming—and we dream of being loved in return. But love—real love—also has no claims, no demands, and even if we know that our case is hopeless, we will always feel profoundly fortunate that this person had once been in our lives. This is how, I would imagine, a six-year old child feels about a grown-up, unattainable woman. And it is a great parable for love.

For Turgenev, love is sacrifice—but not the showy, impulsive sacrifice of Romeo. It is the clear-headed, quiet heroism of putting your comforts, needs, ambitions—and, if it comes to it, your life—on the line for another. I must add that love is when you continue loving someone long after they have stopped being what they once were. Twenty years ago, you might have married Rimbaud. Since then, he became senior brand manager. The most natural thing to do is to leave and look for another Rimbaud. Or maybe even Nietzsche. This is what I have done every time, and I have no regrets. But if you love, really love, you will still recognise in the pointless character on your sofa the glorious youth who once burned and raged and threatened the world with his dreams. And you will stay with him for love—not for pity, or duty, or because it’s the right thing to do. And this, of course, is talent.

It is also where love comes very close to another emotion. Friendship. It is my profound belief that friendship is a nobler feeling than love. Love fizzles out. Friendship—real friendship, not the friendship of shared hobbies—endures. Friendship is light. Love is heavy. When I read “Enter Mercutio,” I perk up, move closer to the page. I know it will be good. When I read “Enter Juliet,” I brace myself for sighs and oaths and all manner of excess. Friendship is simple, it needs no affectation, no embellishment, no multiple exclamation marks. “So you came? How kind.” So says Don Carlos to his childhood friend Marquis de Posa, under circumstances too poignant to repeat (do read Schiller’s Don Carlos. This play is perfection.) Compare this to Juliet’s “O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo?” And, in what is one of the finest images in world literature, The Little Prince’s “Voilà…, c’est tout…” just before the snake bites him and he dies. This is all The Little Prince says to his friend Saint-Exupery. This is all you need to say to a friend.

And finally, friendship—unlike love—has no agenda. It is free. Lovers tend to stay in the same place. Friends’ paths diverge, and diverge widely: we grow up, we move countries, we pursue different passions, other people enter our lives. But, whatever happens, wherever I am, I know that my friend is there. And when I see him again—in a year, or five, or 10—we will pick up where we had left, and it will be easy. It will be easy because our tie is real, it is not based on fantasy, or fear, or desire—but on the unity of mind and spirit, unity that is selfless, and happy, and free. If, like me, you have a friend like this, you know it is the best feeling in the world.

Elena Shalneva is a London-based journalist, writing about books, film, and culture. Her work has appeared in Standpoint and City AM. She has published several short stories, and is currently completing her first collection. She is also guest lecturer at King’s College London. You can follow her on Twitter @ShalnevaE

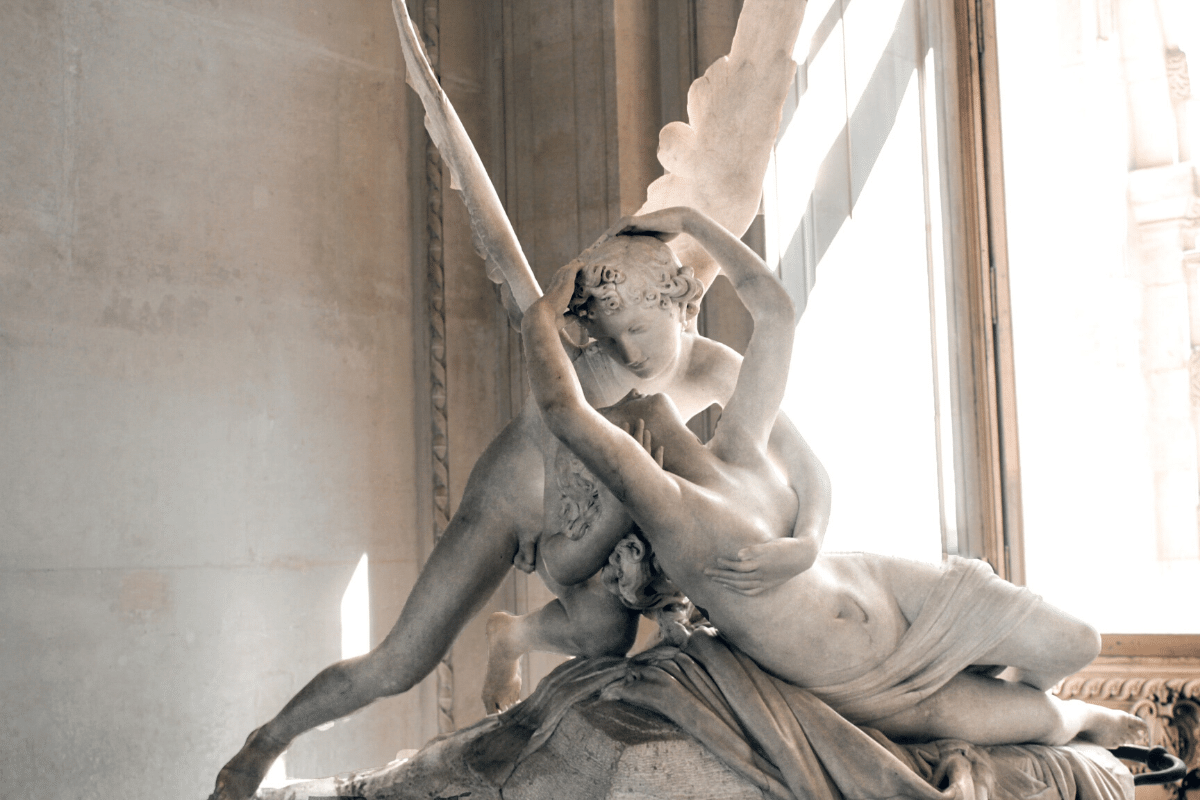

Feature photo by Sara Darcaj on Unsplash