Activism

An Alternative Feminist Perspective on Abortion

The fight to enshrine the right to unrestricted abortion in law is based on ideological feminism’s two main premises: victimization and what I call “undifferentiation.”

Having studied law and worked on the U.S. east coast for three years, I was well prepared for the long-delayed debate about abortion in my native country, Argentina, when it began in March 2018. However, it did not unfold as I expected. Abortion is a crime under Argentine law, except in cases of rape or life/health threatening pregnancies (See Section 86 of the Argentine Criminal Code). Nevertheless, in practice, there are significant differences in how abortion is treated across the country—in some jurisdictions, a woman may find it hard to undergo an abortion in those circumstances exempted by the Criminal Code, while in others, any woman asking for help with an unwanted pregnancy at a public hospital will be advised to declare that it was the result of non-consensual sex or to submit a doctor’s certificate stating that it threatens her mental or “social” health, thereby making her eligible for a free abortion provided by the state.

In Argentina, the debate about abortion divides the population, so I expected the discussion to address its philosophical and ethical dimensions—How does one resolve the conflict of interest between an unborn human life and a pregnant woman? When does human life begin? Should economic profit from abortions and use of human remains be restricted? Should “eugenic” abortions be permitted? Should biological fathers be permitted a say in the decision to abort?—as well as the practical problems posed by a more liberal policy—Who should perform abortions? How can a collapsing public health system respond to the demands of an unrestricted legalization of abortion and effectively deal with the medical complications that abortions provoke without neglecting its existing patients? What are the consequences of abortion for a woman’s health? What time limits should be imposed to account for the fetus’s viability outside the womb and risks to the woman’s health?

But many of these dilemmas were left undiscussed. Instead, we were overwhelmed by a flood of activism that became known in the media as the “green wave” (after the color adopted by supporters of legalization). These activists insisted that the fight for abortion legalization was in fact a “war on patriarchal oppression” and this left many feminists (in the term’s original and broad meaning of defending the principle of equality of rights and opportunities between women and men) confused and disturbed. We could no longer consider ourselves feminists, we were told, unless we fully supported the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy bill, which granted unconditional access to abortion at any time during pregnancy to any woman who tells a doctor that it was the result of a rape or that it threatened her “social health” (a broad term included in the WHO constitution, intended to indicate a “state of complete social well-being”). Furthermore, the bill compelled doctors to perform abortions within five days of a request (even in cases where the doctor judged that the abortion may be unadvisable from a medical perspective). Doctors who refused to comply would face the prospect of jail time, and the bill did not require intervention by the criminal justice system when pregnancies involved the sexual abuse of minors.

The claims and arguments used to promote and defend the bill often left a lot to be desired. Green organizations circulated inaccurate statistics, which were then enthusiastically promoted by local and foreign media. For instance, this tweet sent by Margaret Atwood, the internationally acclaimed author of The Handmaid’s Tale, to Gabriela Michetti, then Argentina’s vice president, received over 17,000 likes and over 8,500 retweets:

Vicepresident of Argentina @gabimichetti: don't look away from the thousands of deaths every year from ilegal abortions. Give argentinian women the right to choose! #AbortoLegalYa #QueElAbortoSeaLey #NiUnaMenos #AbortoEnSenadoYa @cdnwomenfdn @equalitynow

— Margaret E Atwood (@MargaretAtwood) June 25, 2018

Atwood’s emotive appeal neglected to mention that the maximum number of deaths caused by illegal abortions in Argentina during 2016, according to the Argentine Department of Health Statistics and Information (DEIS) (i.e., the number of deaths caused by abortions categorized as “medical abortions, other abortions, non-specified abortions and failed attempts at abortion,” which may also include miscarriages), was not “thousands” but 31 (Report 110, p. 954). That figure fell to 19 for 2017 and 2018 respectively. The New York Times mistakenly reported that, “Complications from these [clandestine] abortions are the leading cause of maternal deaths in the country, researchers say, accounting for 18 percent of all maternal deaths in Argentina.” In fact, that percentage refers to any deaths caused by complications arising from both abortions and miscarriages. (The leading cause of maternal deaths in Argentina published by DEIS in 2018 was “sepsis, other infections and complications relating to puerperium,” and is now “hypertensive disorders, edema and proteinuria during pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium”; i.e., cases in which women undergoing normal, non-interrupted pregnancies, die as a result of infections and other complications related to childbirth.) These data are prepared by the Argentine federal system of public registry and vital statistics, which has been certified by international organizations as “complete, with good attribution of cause of death” and can be compared with data from other countries as a result of DEIS’s participation in the PAHO/WHO initiative on basic health indicators.

On August 7th, 2018, the day before the Argentine Senate rejected the abortion bill, Amnesty International placed a one-page ad in the New York Times depicting a coat hanger on a green background beneath the word “Adiós.”

This is a powerful ad via @amnesty in the New York Times: Complications from unsafe abortions are the leading cause of maternal deaths in #Argentina pic.twitter.com/7ohw96fvM2 #AbortoLegalYa

— Mona Eltahawy (@monaeltahawy) August 7, 2018

This image reinforced a misleading impression of clandestine abortions deployed extensively by the bill’s supporters: crude abortive procedures and surgical interventions, which once caused serious health trauma and sometimes even death, especially to poor and vulnerable women. While tragically correct in the 20th century, this is no longer the case, due to the introduction of Misoprostol which is used to induce expulsion of an embryo. Today, a woman suffering complications caused by a Misoprostol-induced abortion will show the same symptoms as a woman with complications derived from a miscarriage. Whichever ill-fated consequences befall her are not caused by the illegality of her abortion, but by the poor response from the Argentine health system in jurisdictions in which poverty is widespread. This is easily evidenced by the statistical data on female mortality published by DEIS for 2018. In that year, no more than 19 deaths were caused by illegal abortions, while 238 maternal deaths resulted from general obstetric illnesses that were not satisfactorily addressed by the public health system, such as hypertension or puerperal infections (p. 141), and 374 deaths were caused by preventable illnesses typical of poverty, such as tuberculosis and Chagas disease (p. 88).

It was not just a disregard for and misuse of the available data and the absence of reasonable, constructive discussion that disturbed many Argentine women during the abortion debate. Many of us suddenly found that we had been ejected from the feminist movement and redefined as old-fashioned and unenlightened women who, unable to “deprogram” ourselves from patriarchal oppression, had become our oppressors’ collaborators. This came as a shock in a country where most men have not only respected but also steadily supported the expansion of women’s rights. For instance, in 1991, a gender quota for the Argentine Congress was imposed by law and remained in effect until 2017, when it was replaced by the current rule of complete gender parity for candidates to Congress. Furthermore, women play a significant role in government (when the debate started in 2018, the vice-president, the governor of the most important province, and one of the three leaders of the government coalition were all women).

However, the green wave assumed that anyone opposed to the Argentine bill on unrestricted abortion must be an enemy of women’s rights. On August 10th, 2018, 48 hours after the Argentine Senate rejected the bill, the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) released a statement declaring that UN human rights experts deeply regretted the rejection of the abortion bill by the Argentine Senate, and expressing their opinion that, “Legislators of the higher chamber have ensured the continuation of an archaic legacy supported by a religious doctrine that embodies harmful stereotypes of women’s roles in the family and society that are inherently discriminatory and oppressive to women.” The OHCHR ignored the secular arguments made by the great majority of legislators who voted against the bill, and the role played by women in defeating it (14 out of 27 female senators voted against the bill), many of whom had historically fought for women’s rights in Argentina.

From the OHCHR’s perspective, and that of many other organizations and celebrities in Argentina and throughout the world, support for the legalization of unrestricted abortion is an indisputable feminist axiom and moral imperative. The rationale for this view—repeated ad nauseam during the 2018 public debate and still intoned today—is that it is a woman’s capacity to bear children that allows patriarchy to continue to oppress her, and that only by reclaiming her body (that is, by refusing to become an “incubator” for the patriarchy’s benefit) will she truly find emancipation. Thus, in order to enjoy the same opportunities that a man enjoys, a woman must be able to engage in sex freely and without consequence. Unfortunately, a woman can only fully achieve that freedom with an unrestricted right to abortion.

This perspective—which I have previously termed “ideological feminism”1 using Hannah Arendt’s definition of ideology in The Origins of Totalitarianism—holds that, since the patriarchal system oppresses women and appropriates our bodies, we must demand an inalienable right to do with those bodies what we wish, without consideration for the rights or welfare of a child inside them. Otherwise, it is we, here and now, who are perpetuating patriarchy. Thus, the right to abort becomes ideological feminism’s most pressing goal: The female body was subdued; now it must be unconditionally liberated.

The fight to enshrine the right to unrestricted abortion in law is based on ideological feminism’s two main premises: victimization and what I call “undifferentiation.” In connection with abortion, ideological feminism argues that women are victimized twice over: first by the burden of pregnancy, and then by an oppressive patriarchal system that prevents us from taking a decision to abort that pregnancy. (Radical feminism adds a third ground for victimization by casting suspicion on women’s ability to fully consent to sex in the first place due to structural conditions of inequality 2; although this final claim was not made explicit during the Argentine debate, it may explain the repeated use of rape cases to justify the legalization of abortion, even though sexual abuse is already an exception to abortion’s punishability in Argentina.)

The dogma of “undifferentiation” results from a confusion between (or conflation of) the aspiration that women and men enjoy equal rights and opportunities of personal development and participation in public life, with the aspiration that women and men be made biologically indistinguishable—in other words, that women must possess a body freed from the biological ties imposed upon us by our capacity to gestate. This impulse may arise from a subconscious desire to adapt to a world that is still mostly male (since women have only recently begun to fully participate in its construction), but it creates a paradox—aspiring to the bodily freedom enjoyed by men seems to imply a male body’s superiority.

There is an alternative feminist perspective, however, in which the legalization of unrestricted abortion not only fails to put an end to the oppression of women but perpetuates it. Historically, abortion has been one of the most extreme manifestations of patriarchal oppression. Women have traditionally sought an abortion because they were compelled or pressured by parents, partners, abusers, or employers. Some did so simply to avoid the stigma and shame conferred by relationships that violated a society’s moral codes. Others aborted because abandonment or neglect left them unable to bear the responsibility of child-rearing alone, or because abortion offered the only escape from unwanted pregnancies imposed by an abusive partner. All these motivations are still present, of course, especially for uneducated or economically dependent women. But in a country with unrestricted abortion, they are more easily disguised under the veil of legitimacy provided by the contention that abortion is a women’s inviolable right. Today, a vulnerable woman seeking help with an unwanted pregnancy at a public hospital in Buenos Aires will more likely than not be advised to have a “legal interruption of pregnancy” (under one of the two exemptions provided by our Criminal Code) and be sent home with a free dose of Misoprostol. She is unlikely to obtain effective help to either keep her child or give it up for adoption (free choice is a scarce resource for vulnerable women).

Furthermore, the past decades of unrestricted abortion in many countries have created additional pressure on women, not individual and explicit, but generalized and unspoken: the need to compete with men under equal conditions. The decision to abort is today as affected by ideological feminism as the choice to sacrifice personal development in order to procreate was affected in the past by patriarchal culture. This new limitation on a woman’s freedom, internalized to the extent that it becomes part of her conscience, is more common in educated and economically/socially successful women. The higher the professional development of a woman, the greater her conviction that she must sacrifice or postpone motherhood to compete effectively. This, notwithstanding the fact that scientific advances, a greater comfort in domestic life, and significant increases in life expectancy ought to allow her to combine her professional development with a full realization of her maternal role.

This might be attainable if life in society were organized to correct for the greater weight carried by women in human procreation. Under an unrestricted abortion rule, the “right to abort” becomes the safeguard that allows women to postpone or sacrifice motherhood in order to compete with men under equal conditions when all other precautions taken to avoid pregnancy have failed. And because such a safeguard exists, a woman who makes the decision not to “exercise her right” to be equal to a man, and instead accepts and protects her wanted or unwanted (as well as professionally ill-timed) pregnancy, relegates herself in a system that is still defined and ruled by men’s timing and bodily freedom. This is an individualistic and materialistic system in which a woman can only prevail over a man if she is willing to emulate him, postponing or sacrificing her maternal role in order to be able to develop economically and professionally in full, even to the point of inflicting violence on her own body and the body of the human being she is carrying inside it.

The ability to gestate is a woman’s most significant distinction in the developed world today, where the comparative weakness of a woman’s body has ceased to be a determining factor in accessing the means of production, and where the justice system guarantees that a man will not be able to physically subdue her without punishment. This essential characteristic of women—which has not been artificially replicated yet and is therefore necessary for the preservation of our species—has not been imposed on women by men or patriarchy but by biology. At a time when we value diversity, ideological feminism’s emphasis on describing a woman’s body in terms equivalent to a man’s (a body “free of ties”) demonstrates once again that humanity is still making the mistake of considering men, in their individuality and biological freedom, as the standard of normality.

Women should not have to choose between professional development and the fulfilment of our capacity to bear children. Today, more than ever, scientific, technological, economic, and cultural conditions allow us to share our burden in childrearing on an equal basis with men. Alternatively, we can choose, by using education and contraception, not to participate in those tasks. As a result of effective public health policies, pregnancy and childbirth no longer pose life and health hazards to women. The maternal role—still essential during the first years of childrearing—may be facilitated and shared by men and the general community thanks to technological advances (which have exponentially increased people’s organizational capabilities) and economic growth. We can use this new freedom and flexibility to compensate women for the heavier burden they bear in the crucial task of preserving the human species. Many complex problems—including abortion—still need to be addressed if we are to achieve that goal. But none will be solved without freedom of thought, pluralism of opinion, and scientific knowledge, least of all by blindly supporting conclusions presented as logically derived from the “fight against patriarchal oppression.”

For those of us who believe that the duty to protect human life includes a duty to protect unborn human beings, there is still hope that someday feminism will leave behind its proclivity to indulge in victimhood and an unconscious aspiration to maleness and will regain its pride in women’s capacity to gestate and rear children, fighting for its recognition and protection. This hope is based partly on the real experience of millions of women who still find in pregnancy and maternity an intimate and extraordinary existential satisfaction, and partly on the admirable human ability to start anew.

References:

1 Poratelli, S. (2019). El feminismo ideológico y el aborto. Revista Argentina De Teoría Jurídica, 20(1), 113 – 141. Available at http://revistajuridica.utdt.edu/ojs/index.php/ratj/article/view/326.

2 MacKinnon, C. (1983). Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: Toward Feminist Jurisprudence. Signs, 8(4), 635-658. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3173687

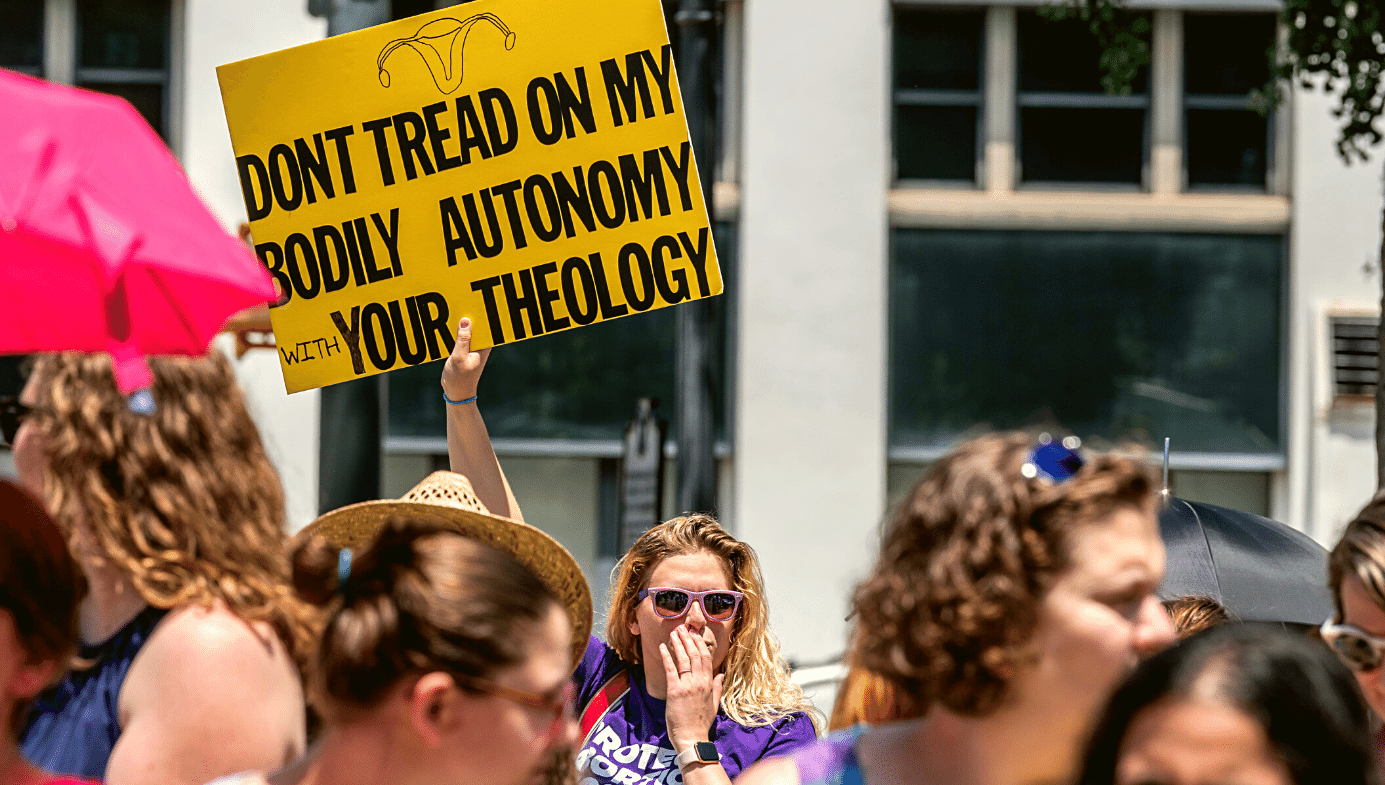

Featured Image by Paula Kindsvater (wikicommons)