Bioethics

Peter Singer and the Narrowing of Discourse

The implications of this narrowing of discourse for public debate and the exploration of ideas are dire, and reflect a growing surrender to intolerance at the expense of rational discussion and analysis.

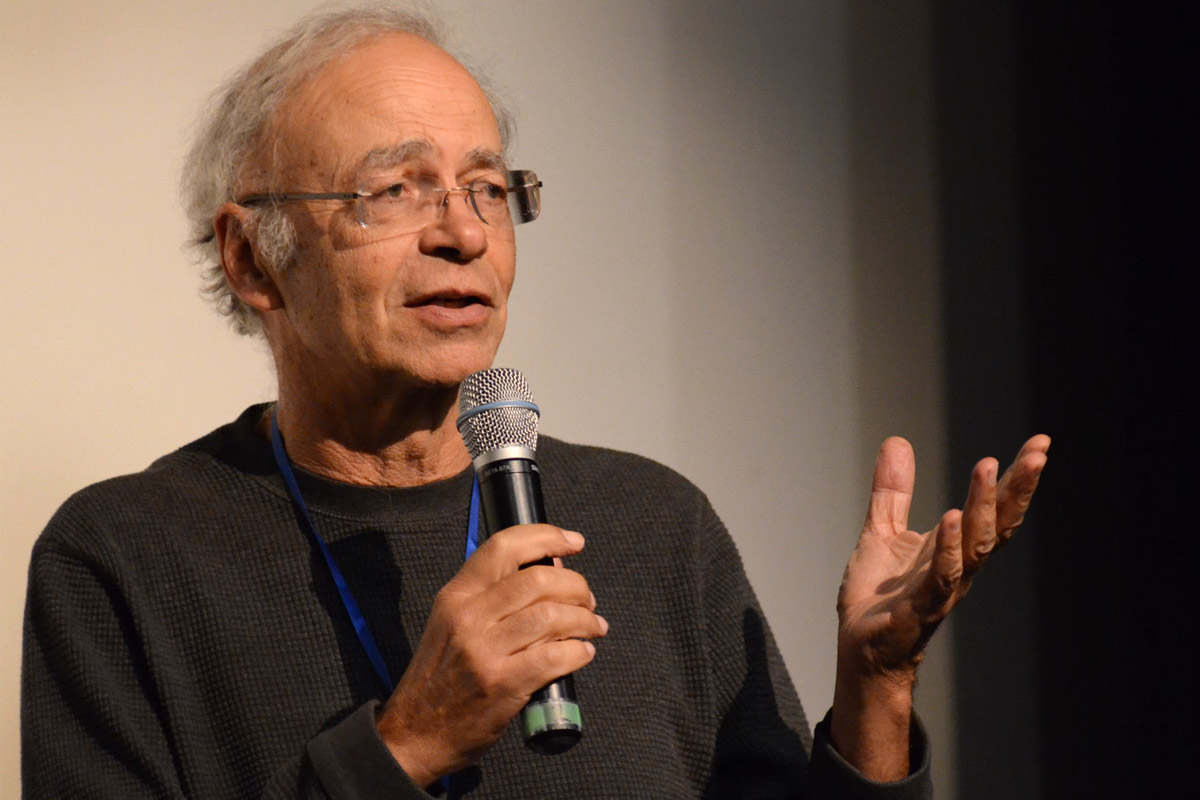

You might expect a row between a moral philosopher and a casino company to involve the former lecturing the latter on the ethics of profiting from gambling. But it is Peter Singer, sometimes called “the world’s most influential living philosopher,” who finds himself rebuked by SkyCity, New Zealand’s biggest promoter of poker machines. Singer had been booked to speak at a SkyCity venue as part of a ThinkInc tour to raise money for his charity The Life You Can Save, which seeks to reduce global poverty. But then an article appeared on New Zealand webzine Newshub reminding readers of Singer’s longstanding views on infanticide. “New Zealand’s disabled community is outraged a controversial Australian philosopher who justifies infanticide is being allowed to speak here,” Newshub reported. “Peter Singer, who’s been described as the most dangerous man in the world, has argued it’s ethical to give parents the option to euthanise babies with disabilities.”

The report went on to compare Singer to ethnonationalists. This “wouldn’t be the first time a controversial speaker had been barred,” the site reported. “After public outcry alt-right activists Stefan Molyneux and Lauren Southern had their event cancelled in 2018 over ‘security and health and safety concerns.’” SkyCity responded by cancelling the venue hire agreement. According to the New Zealand Herald, the company feared “reputational damage.” A statement further explained that, “Whilst SkyCity supports the right of free speech, some of the themes promoted by this speaker do not reflect our values of diversity and inclusivity.”

Whatever one thinks of Peter Singer’s philosophy, the idea that he is in any way comparable to Molyneux or Southern is a calumny. Singer is currently professor of bioethics at Princeton University, where he works in the Center for Human Values, and a laureate professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at the University of Melbourne. In 2005, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. In 2012, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia for “eminent service to philosophy and bioethics as a leader of public debate and communicator of ideas in the areas of global poverty, animal welfare, and the human condition.” Singer has written dozens of books on philosophy, some of which have been highly influential. His 1975 bestseller Animal Liberation has had a profound impact on the animal rights movement. His 2009 book The Life You Can Save and 2015’s The Most Good You Can Do have been important in advancing the cause of the growing effective altruism movement. The former, which explored our moral responsibility to alleviate poverty with charitable giving, was endorsed by Bill and Melinda Gates in these glowing terms:

Peter Singer challenges every one of us to do more, to be smarter about the ways we go about giving, and shows us that, working together, we can make a profound difference in the lives of the world’s poorest.

It is hardly surprising given the breadth of Singer’s interests, the rigour with which he pursues the logic of utilitarianism, and the hair-trigger sensitivity of our cultural moment, that some of his ideas remain highly controversial. Consequentialist thinking makes many people uneasy, since the pursuit of desirable ends can be used to justify repugnant means, and Singer has been unafraid to explore some of the most taboo areas of bioethics, of which infanticide is perhaps the most emotive.

Confronted with the prospect of moral condemnation, SkyCity may simply have taken a pragmatic decision to terminate the event in order to avoid an ugly scandal. If that’s the case, then their pieties about “diversity and inclusivity” are simply a cynical attempt to turn adversity to advantage. Alternatively, it is possible that SkyCity’s corporate social responsibility group were hitherto unaware of Singer’s views and so appalled when they learned of them that they felt morally bound to deplatform him, even though he’d been invited to speak on an unrelated topic.

Companies like these, after all, do not exist to defend the holders of uncomfortable ideas. They are primarily concerned with remaining attractive to customers, suppliers, politicians, and anyone else who might potentially affect their business. Brand protection requires constant vigilance. Eric Crampton, a New Zealand commentator, speculates that SkyCity cancelled Peter Singer’s appearance because they “fear the ill-will” of the gambling regulator. If so, then a gambling company has prevented a professor of ethics from delivering a speech about the importance of charity because it feared scrutiny from its regulator. This bizarre state of affairs does not bode well for public debate in Auckland, given that SkyCity will soon run the city’s new convention centre.

Of course, there will doubtless be some backlash from Singer’s supporters and disinterested defenders of free inquiry, but SkyCity seems to have calculated (and they are almost certainly correct) that they can weather that particular storm more easily. But while it may be understandable that the company opted for the path of least resistance in our feverish cultural climate, it is also deeply regrettable.

I am personally unpersuaded by Singer’s defence of infanticide, but we’re in trouble if scholars of his seriousness and stature have their speaking invitations rescinded on account of moral outrage ginned up in the press. In the Newshub report that first raised concerns about Singer’s Auckland appearance, disability rights advocate and multiple sclerosis sufferer Dr Huhana Hickey explained that Singer “has every right to freedom of speech, [SkyCity] have every right to host him. I have every right to protest and to counter his speech around disability.” Unfortunately, in both the real and the virtual worlds, “You have a right to speak and I have a right to disagree” has been superseded by “Your opinions are unacceptable and you must be shunned.”

Thanks to social media and the blogosphere, a small but vociferous group of ideological or vindictive individuals can have a wildly disproportionate effect in the public square. This can cause their target great personal distress, reputational harm, and the consequent forfeiture of employment opportunities and income. In an environment characterised by superficial judgments, rigid sanctimony, and guilt by association, anyone on the target’s periphery risks becoming collateral damage. That includes venue owners who extend invitations to controversial speakers.

It is inevitable that writers and thinkers and those who offer them platforms will respond by becoming more risk averse. The implications of this narrowing of discourse for public debate and the exploration of ideas are dire, and reflect a growing surrender to intolerance at the expense of rational discussion and analysis. Of course, in some quarters, this is viewed as an entirely positive development. What’s wrong, they ask, with silencing those who defend the killing of infants? But this is exactly the sort of fanatical thinking that suppresses debate—you either agree with me or you’re morally repulsive. Setting aside the axiomatic value of free speech in a liberal democracy, there is also the practical difficulty of who gets to decide what the rest of us are allowed to hear. In a free and pluralist society, the answer can’t possibly be self-appointed Twitter mobs.