Must Reads

Thatcher Warned Us to Go Slow on European Integration. Too Bad We Didn’t Listen

She believed that Europe should not be a centralizing power that incubated supranational institutions—particularly as this model of centralization was just then in the throes of spectacular failure within the Soviet Union.

This November will mark 30 years since former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher left office. After she had narrowly failed to secure an outright win in a 1990 leadership contest triggered by a challenge from Michael Heseltine, her former defense secretary, the majority of Thatcher’s Conservative cabinet colleagues withdrew their support and forced her departure following what she described as “eleven-and-a-half wonderful years.”

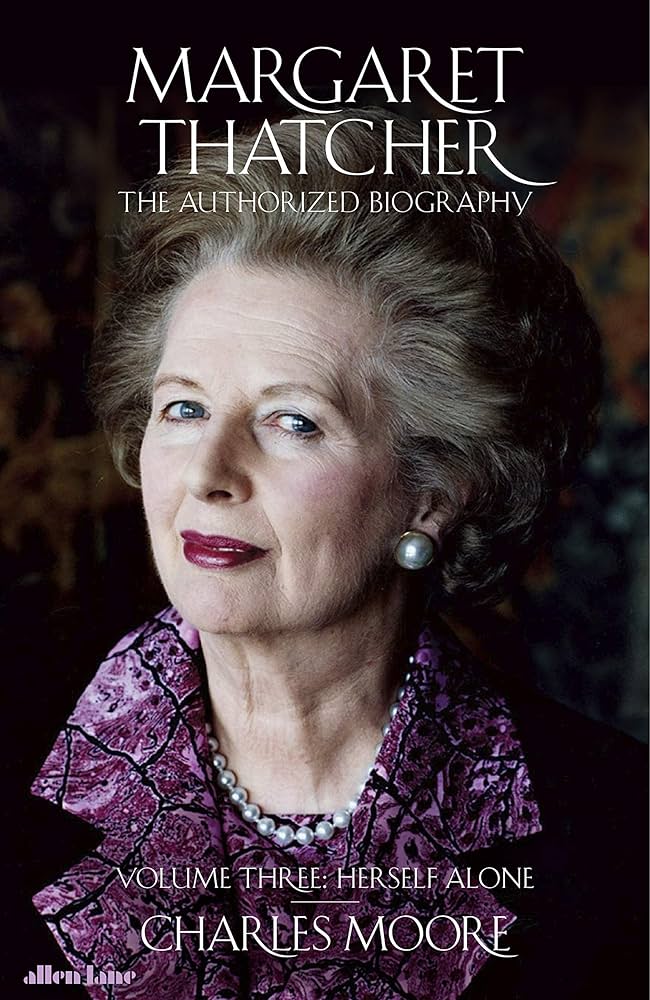

For Thatcher, the “coup,” as she referred to the events of 1990, had been unexpected. But as journalist Charles Moore explains in the third and final volume of his authorized Thatcher biography, Herself Alone (2019), the writing had been on the wall for some time. Thatcher’s style, which some considered abrasive, had turned senior figures against her. And many younger party members believed that if the party were to win a fourth consecutive election victory, in 1991 or 1992, it should be under a new standard-bearer (who turned out to be John Major).

An important underlying factor was the long-standing policy conflict regarding the European Community (or the EC as the European Union was then known), which pitted Thatcher against many in her own government, as well as against continental European leaders and George H. W. Bush’s White House. She was perceived as a “Cold Warrior” who was overly cautious in regard to the future of Europe, especially the project of European political and economic integration.

To some modern observers, that criticism of Thatcher remains apt. In a recently published book on international relations authored by former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt, The Age of Disorder (Den nya oredans tid, 2019), Thatcher’s reluctance to endorse a speedy German reunification is attributed to her obsolete anxieties regarding “the dangers of a strong Germany.”

Moore’s latest volume, which focuses extensively on Thatcher’s views about Europe, shows her in a more nuanced light. In some ways, in fact, she was actually ahead of her time. And some of the current problems facing Europe, and the West more generally, might have been mitigated had her opinions been given a more generous audience.

* * *

It is clear from Moore’s account that Thatcher did oppose—“dread” is perhaps not too strong a word—a united Germany becoming the dominant European power. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, she apparently was “appalled to see pictures of Bundestag [members] singing Deutschland über alles, which she described as ‘a dagger in my heart.’” Nevertheless, Moore writes, her primary concern lay not with the Germans themselves, but with the Soviet Union (which did not fully expire until 1991) and the future of East–West relations.

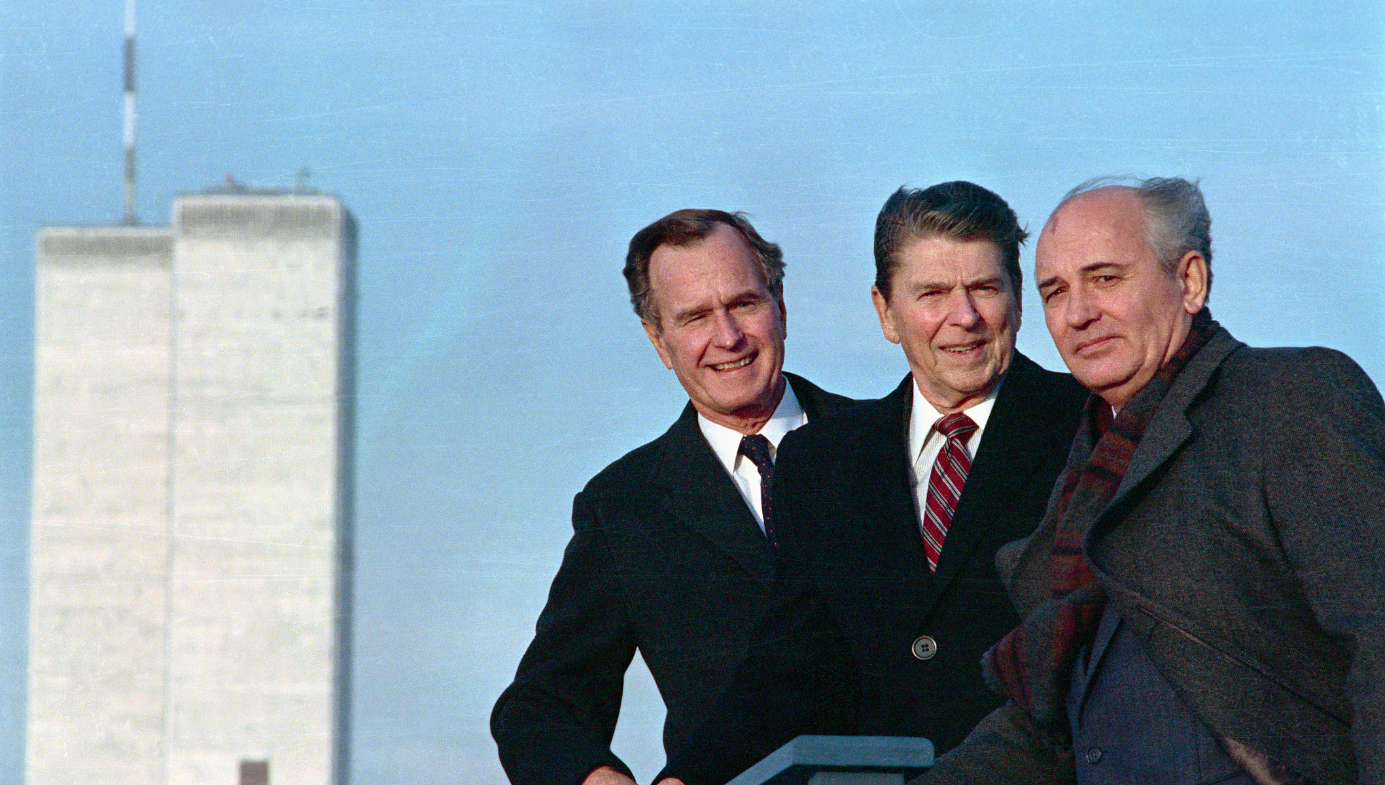

Thatcher had been the first major western political leader to engage Mikhail Gorbachev. She supported his reforms of the Soviet state, and they built a trusting relationship that proved crucial to the winding down of the Cold War. When the wall fell, she worried that an overly swift reunification of Germany would be seen as a humiliation by Soviet hardliners, who might then undermine Gorbachev. (“I fear,” she said, “that he will feel isolated if all the reunification process goes the West’s way.”) As history shows, these were hardly idle fears.

Thatcher also rightly believed that the post-Soviet era would be more geopolitically complex and uncertain than the Cold War. While others rhapsodized about the possibility of a world without serious conflict, she argued that it was important to establish frameworks for co-operation beyond Europe; and, in Moore’s terms, “to turn the Soviet Union into a co-worker for European peace rather than an eternal opponent.” In line with this conciliatory approach, she advocated for a transition period that would precede German reunification, and for involving the Soviets in a discussion over Germany’s future, together with the other “Four Powers,” which had been responsible for Berlin since 1945. These ideas, however, were rejected, in part because German reunification was seen as “a critical step to delivering Bush’s vision of a Europe ‘whole and free.’” Reunification took place in October 1990, shortly before Thatcher stepped down.

According to Moore, the end of the division of Germany was a factor in the attempted coup against Gorbachev in 1991. He also points out that one of the Russians who became convinced that his country had been humiliated by the West during this period was none other than Vladimir Putin, then serving as a KGB officer in East Germany.

And so it is somewhat ironic that Thatcher is remembered by her critics as an inflexible Cold Warrior: At this critical juncture, she had argued for being more sensitive—not less—to the perspective of Russians. Had her advice been heeded, the Russians might have felt less slighted, and the last 30 years of East-West relations might have unfolded differently.

Thatcher’s arguments and warnings over the issue of European integration were similarly pushed aside. And, as with the USSR, the nature of Thatcher’s objections have been mischaracterized. In a major speech about the future of Europe, delivered in Bruges on September 20th, 1988, she “began with a grand historical sweep, taking in the Romans, Magna Carta, the Glorious revolution and much more, all designed to show that Britain was part of European civilization.” Thatcher also made it clear that “Britain wanted no ‘cosy, isolated existence’ on the fringes: ‘Our destiny is in Europe, as part of the Community.’”

What Thatcher did oppose was the project of “ever-closer union,” and the resulting weakening of the influence of nation states. She believed that Europe should not be a centralizing power that incubated supranational institutions—particularly as this model of centralization was just then in the throes of spectacular failure within the Soviet Union. Instead, as she outlined in a speech at The Hague on May 15th, 1992, she favored a looser form of European co-operation, by which states retained their sovereign freedoms—including control of their borders. This, she believed, would accommodate the political and cultural diversity of Europe, including the eastern European countries that, she hoped, would be offered full EC membership. As Moore notes, in fact, she was one of the few prominent European politicians of the 1980s who had recognized that cities such as Warsaw, Prague and Budapest were very much European cities that had been cut off from their historical and cultural roots.

In her speech at The Hague, as Moore summarizes it, “she prophesied that large-scale immigration caused by free movement would cause ‘ethnic conflict,’ and bring about the rise of extremist parties, that there would be ‘national resentment’ because of one-size-fits-all financial and economic policies under a single currency, and that a more centralized EC would not be able to work with the influx of new member states from the former Eastern Bloc.”

This obviously has specific relevance to Brexit and the political forces that led to it (though Thatcher herself, who died in 2013, never lived to see any of this play out). More generally, the common thread is that Thatcher understood the pattern of reaction and counterreaction that governs human affairs, including affairs of state. She stuck by the hard lessons of history even as others around her surrendered giddily to the fin de siècle euphoria that accompanied the end of the Cold War.

It must be conceded that her concerns about counterreaction—both within Russia, and among Europeans who did not want to lose their national cultures and political prerogatives—proved at least somewhat prophetic. The same goes for her warning of “the emergence of a whole new international political class,” ignoring people’s shared instincts and traditions. As discussed by others—including the journalist Douglas Murray in his 2017 book, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam—this comprises a major issue in the European Union to this day. What a shame that when Thatcher warned us of its rise, she was, to quote Moore’s title, herself alone.