journalism

As Newspapers Fade, Journalists Are Finding New Ways to Cover Local News

Less local reporting means less transparency, less informed voters, and lower levels of civic engagement.

Until January 2019, reporter Tim Swarens had devoted his entire 35-year career to journalism—the last 15 years spent as a reporter and editor at the Indianapolis Star. The end came as a shock. “I did not expect to end my career by being walked out the door by security,” he told me over coffee.

His work had earned him awards from numerous prestigious bodies, including the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, and the Eugene C. Pulliam Fellowship for Editorial Writing. He loved his job, and assumed that his reputation would allow him to do it until retirement: “For me, there was never any alternative to being a journalist.”

According to a recent Pew Research Center study, the number of newsroom employees at U.S. newspapers declined by nearly half between 2008 and 2018, from about 71,000 to 38,000. In some cases, contractions or shutdowns at major-market outlets (such as the Chicago Tribune) receive coverage in other publications. But the situation is even more troubling in smaller markets that are served by few local media. Newspapers such as the Star in Indianapolis are facing challenges because the traditional business model they relied on for much of the last two centuries—advertising, paid-classifieds and subscriptions—has collapsed. Moreover, unlike the Washington Post and other elite publications that are read nationally and internationally, regional publications are selling content into a limited local market.

Source: Pew Research Center

Newspaper circulation is now lower than it was in the 1940s (when the number of households was a third the current level). Ad revenue—which peaked, in inflation-adjusted 2014 dollars, at $67 billion in the late 1990s—fell below $20-billion in 2014. According to a report commissioned by the Interactive Advertising Bureau, overall U.S. digital ad revenue in 2018 was over $100 billion, which sounds like good news. But newspapers have been able to access only a small part of this market (only $3.5 billion in 2014), as Facebook, Google and Amazon have captured at least half of all digital ad buys.

Thanks to the steady stream of sensational political stories generated by Donald Trump, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal have enjoyed considerable gains in digital circulation. But high-profile successes such as this are few in middle America, where a single local newspaper may be the difference between accountability and impunity for politicians. Less local reporting means less transparency, less informed voters, and lower levels of civic engagement.

The weakening of local newspapers means that public discourse has become increasingly nationalized, which has contributed to political polarization and social fragmentation. Instead of focusing on local and regional campaigns that invite effective citizen mobilization and activism, such as ensuring the quality of schools, roads and utility networks, Americans increasingly treat politics as a subject of national-level gossip and entertainment.

Randy Shepard, a retired Justice on the Indiana Supreme Court, has taken to counting the local stories the Indianapolis Star covers each day. “The most common number of locally written stories in a given [edition] is five,” he told me. “Six runs a respectable second. Every once in a while, there are just four, not counting sports.” The rest consists of syndicated content.

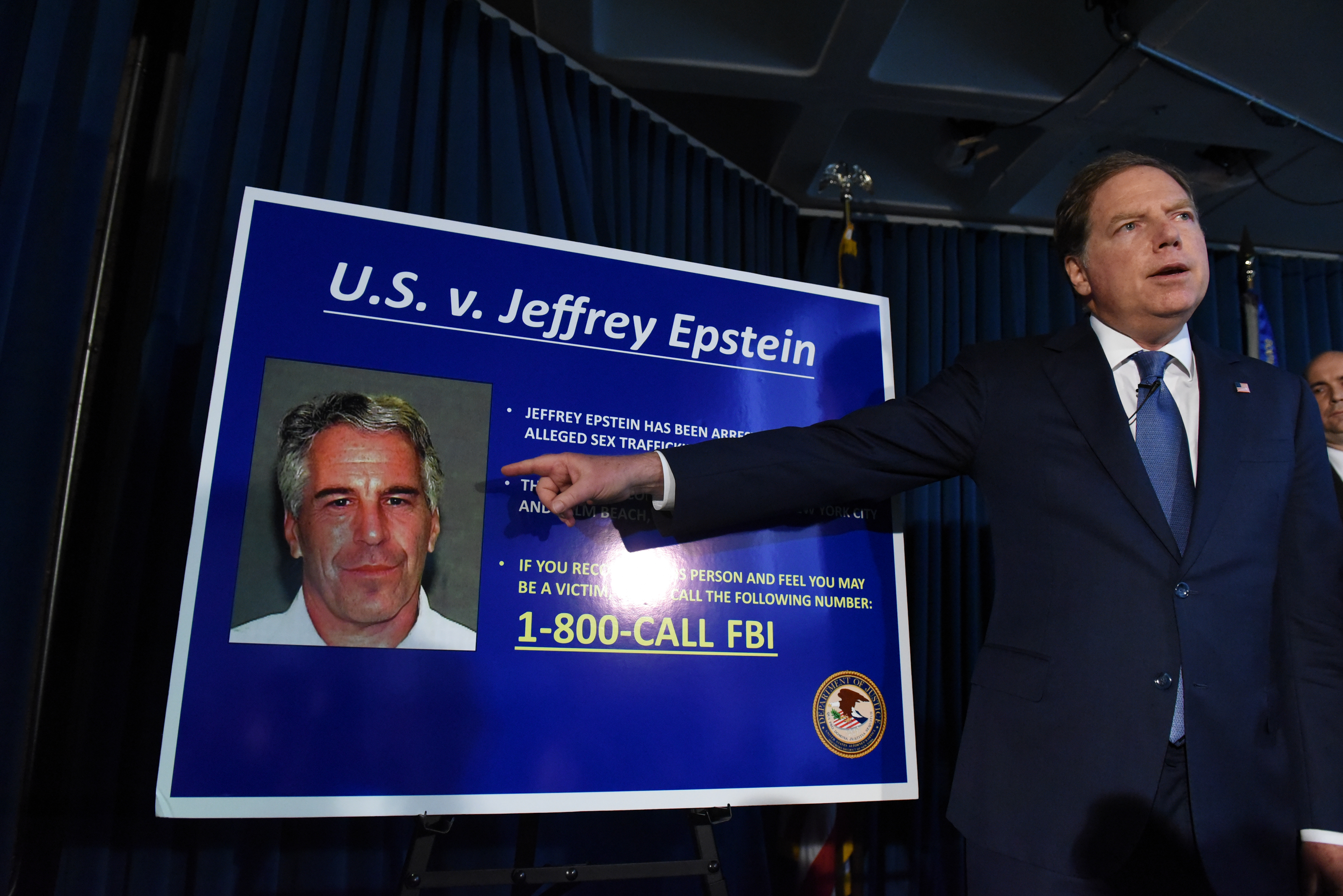

Good regional reporting often is the key to breaking important national stories. For instance, the Jeffrey Epstein case was all but dead until Julie K. Brown of the Miami Herald breathed life into it with her in-depth reporting. The Boston Globe spent years investigating sexual abuse perpetrated by Catholic priests, a project that inspired journalists in other cities to do their own digging. A series of articles by Brian M. Rosenthal at the Houston Chronicle unveiled massive and systemic issues in Texas, with special-needs children being denied education services.

As for Swarens, he was on the edit desk when the Indianapolis Star broke the Larry Nassar sexual-abuse scandal—a project that consumed the efforts of two reporters for five months. In another era, it was routine to devote editorial staff to this kind of story. But today, it’s rare. And a world without this kind of reporting is a world in which the disgraced USA Gymnastics doctor might still be molesting teenage girls.

The challenge for experienced journalists such as Swarens is to find new outlets for their work. And in this respect, there is some good news. The same Pew report detailing a 47% decline in newspaper editorial employees between 2008 and 2018, from 71,000 to 38,000, also found a large uptick in employment in “digital-native” newsrooms, from 7,000 to 13,000.

Many of these new workers are filling the local-news void. Patch, founded in 2009, is an online-only network of platforms owned by Hale Global that, as of mid-2019, operated over 1,200 news websites. Block Club Chicago, Voice of San Diego, MinnPost, the Texas Tribune and the Colorado Sun—founded in 2017, 2005, 2007, 2009 and 2016 respectively—are examples of digital native outlets that have adopted a non-profit, subscriber- and donation-based online model that operates at relatively low cost and focus heavily on a defined local beat. (And not all new ventures are abandoning print. This includes the Provincetown Independent in Massachusetts, which serves the Outer Cape Cod areas of Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet and Eastham.)

Typifying the young journalists who are pioneering these new experiments is Mónica Guzmán, co-founder of the Evergrey, a hyper-local daily newsletter that began serving Seattle in 2016. When the city’s Post-Intelligencer closed in 2009, the 146-year old newspaper still had 117,600 readers. Guzmán observed changes in her community that she believes could be traced to the Post-Intelligencer’s demise, including declining civic engagement and morale.

The Evergrey is one of several new local outlets started up through WhereBy.Us, a self-described “platform for community media businesses.” Revenue flows to the publication directly from subscribers and from ads embedded in the newsletter. The hyperlocal nature of the publication makes it attractive to clients looking to promote events. Sponsors such as the Seattle-based Gates Foundation also have committed to supporting the Evergrey, and their contributions are noted through the display of corporate logos—though the supporters do not have any editorial say in the selection or content of the associated articles. (This is important, because the line between legitimate editorial content and “branded” or “sponsored” content has become the source of controversy in some areas of the industry.)

A larger revenue stream originates with so-called client-created content, such as the material prepared for Vulcan Inc., a network of organizations and initiatives founded by philanthropist and Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen (1953-2018). The Evergrey created content dedicated to commemorating Allen’s legacy, and produced videos featuring local “catalysts” in Seattle, such as a venture capitalist who invests in entrepreneurs of diverse backgrounds, and a resident who started “Civic Saturdays.”

One common characteristic of these newer digital-native operations (including Quillette) is that they operate with lean staffing. The Evergrey, for instance, has just three full-time employees and one part-time manager. But they are supported by centralized WhereBy.Us staff who offer assistance in video production, illustration, event planning and other specialized support services. The Evergrey doesn’t yet have the capacity to dedicate itself to in-depth investigative work. But it does provide an outlet for daily local news reporting.

As for Swarens, he’s leading a group of journalists who are studying all of these models, looking for one that would be right for Indianapolis. They haven’t gotten a name yet, but the above-described precedents show us what the outlet’s defining properties likely will be: timely online content delivery, a flexible revenue model built around subscriber engagement and corporate partnerships, a specialized focus on local news, and lean staffing. “It will take time to build a sustainable institution,” Swarens told me, “but this is [an] important project for our city, state, and country.”

Alexandra Hudson, an Indianapolis-based writer who has been published in TIME, The Wall Street Journal, Politico Magazine, and others outlets. She is a 2019 Novak Fellow currently writing a book on civility, civil society and civic renewal. She Tweets at @LexiOHudson. To read more of her work, visit www.alexandraohudson.com.