Free Speech

Behind the Great Firewall

For the most part, the Great Firewall (GFW) is irrelevant for the average Chinese citizen, mostly irrelevant for most Chinese netizens, and for many of the rest it protects their ability to make money.

There is a thriving community of Westerners in China making and posting videos on YouTube about their lives and experiences there. That may sound odd since YouTube, along with literally hundreds of the world’s other most popular websites, is banned in China. Anyone in the country wanting to connect to YouTube (and/or Facebook, Instagram, Google, Wikipedia, etc.) needs to purchase a Virtual Private Network (VPN); software for a phone or computer to disguise its IP address and which enables the user to circumvent the infamous Great Firewall of China. The legality of VPNs in China is another question altogether: selling a VPN is illegal, owning one is iffy, and using a VPN is ubiquitous–but also draws suspicion. Exact numbers are hard to come by but estimates suggest that more than 30 percent of internet users in China have a VPN installed on at least one of their devices. Like so many things in China, legality is often a question of circumstance and usually not even the most important question.

YouTubers in China run the gamut of video genres. Stylists, adrenaline junkies, travel documentarians, foodies, nature explorers, language explainers, cultural examiners, pop culture nerds, gamers, even political pundits. This last category probably sounds especially strange since the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is one of the world’s most censorious states. In addition to blocking hundreds of foreign websites, the Chinese government also actively attempts to monitor for and restrict entire subjects of conversation and research on the Chinese Internet and Chinese social media. Often, to Western eyes, with inescapably Orwellian intent, design, and results.

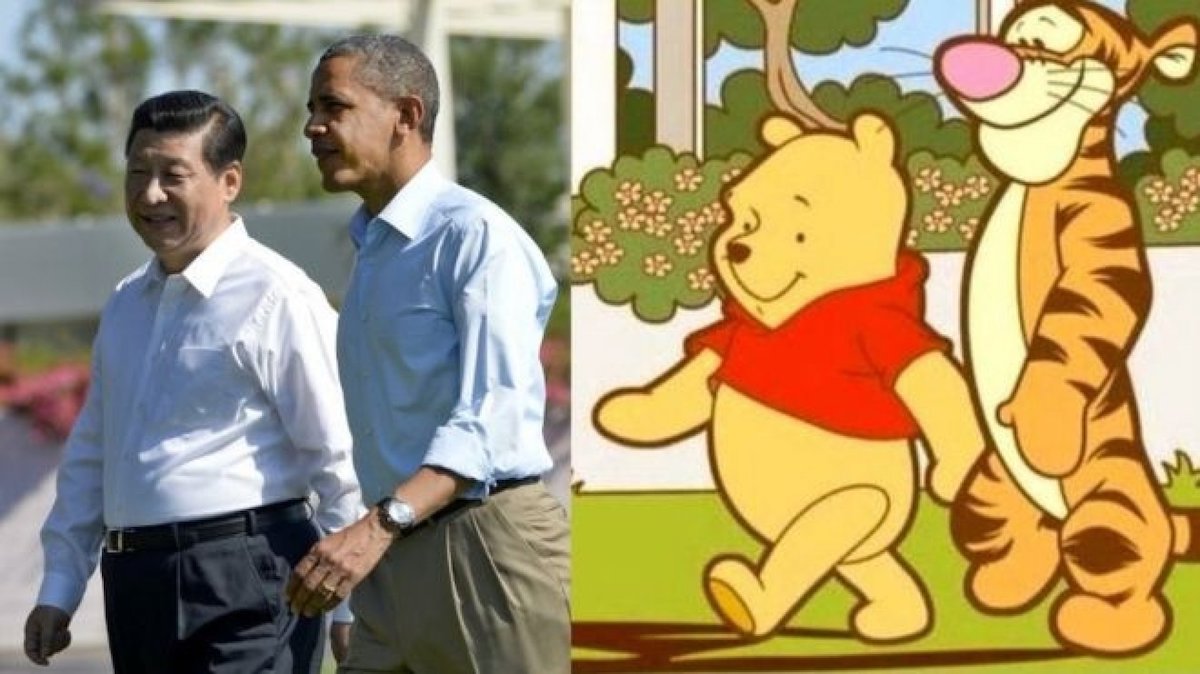

After a meme (below) comparing Winnie the Pooh to Chinese leader Xi Jinping went viral on Chinese social media, the authorities effectively banned images and mentions of the bucolic cartoon bear. Following an especially irreverent episode mocking the Chinese leadership and their predilection for censorship, the cartoon South Park was unironically banned from the Chinese internet. The numbers 4, 6, and 89, are occasionally flagged for their reference to the Tiananmen Square massacre on June 4, 1989. The letter “N” was banned for a short time. The list of restricted subject matter is as comical as the reasons for the bans are dangerous.

But all of these things are banned from the Chinese internet, so as long as someone is armed with a VPN they can post videos to YouTube about whatever they want. Except they can’t. Not without consequence. Over the last four years or so the Chinese authorities have begun using a variety of tactics to clamp down on competing narratives in the country. They have been helped by jingoistic Chinese trolls, collectively known as wumao, an online army of self-appointed censors who may be more harmful than the government itself.

The Limits of Community

Winston Sterzel lived in China for almost 15 years; in early 2019 Winston and his wife left the country, possibly for good. Originally from South Africa, Winston made a life for himself in China. He had sizable friendship and professional networks, married a local woman, spoke Mandarin, and ran the SerpentZA channel on YouTube, the platform’s most-viewed China channel. SerpentZA’s videos are immensely popular, both inside and outside of China. SerpentZA’s content was classic YouTube, video diaries of his life in China with first-person, often very personal, commentary showing the world what he loved and how he lived in China.

Outside of China, his YouTube posts are now among the most watched China video content on the entire Internet. Inside of China, Winston was something of a low-level celebrity. He’d been interviewed many times by state and local news and would even be recognized by everyday people in the street. “Once, in a restaurant, the waiter stared at me for a long while before finally asking me if I was ‘laowai kan zhongguo 老外看中国,’ the foreigner who sees China.” This may also need explaining: YouTube is banned in China, VPNs are of dubious legality, so how are Chinese people watching YouTube videos?

Apart from the ubiquity of VPNs in China, protecting intellectual property isn’t just a problem for big tech companies looking to expand into the Chinese market. Winston discovered he had millions of Chinese fans who had never even been on YouTube. He was constantly approached by Chinese fans explaining that they saw his videos on Chinese streaming sites. “This is how China works,” says Winston, “they take your property and make it their own.” Even fewer Westerners are on Chinese social media than Chinese are on Western social media so there is little chance of thieves ever being discovered and, while intellectual property and creative content theft is common in China, the theft is always going towards China, not away.

This is not a function of government censorship but rather a function of benign neglect—the government doesn’t invest much at all in copyright protection and does even less to protect foreign-owned content. For the most part, the Great Firewall (GFW) is irrelevant for the average Chinese citizen, mostly irrelevant for most Chinese netizens, and for many of the rest it protects their ability to make money.

How Chinese people view the Great Firewall

The everyday Chinese couldn’t care less that YouTube is banned when they have domestic streaming services like Bilibil and Youku. Who needs Facebook or Paypal when you have WeChat, a far superior—but with even fewer data and privacy protections—combination of the two? The vast majority of the content on Google, Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and YouTube is not available in Mandarin anyway so even if the Chinese had (legal) access to those sites, it isn’t like their lives would be enriched to any significant degree. Especially when permitting foreign business can be detrimental to China’s growth, stability, and prestige.

For many, the Great Firewall is just smart business. The absence of Western apps and websites encouraged the development and adoption of viable Chinese alternatives. Blocking Facebook allowed the growth of WeChat. Banning Wikipedia and Google prompted the creation of Baidu. After the Century of Humiliation and decades of being known for cheap labor and as the “factory of the world,” it is a source of immense pride for Chinese to have homegrown products and services of their own as good as, arguably better in some cases, what the West offers.

The Chinese that do venture beyond the GFW, by using a VPN at home or by traveling or living abroad, are also constantly confronted by a world seemingly antagonistic to, or at least at odds with, the People’s Republic. They find a disturbing lack of positive China stories in Western media and a dystopian portrayal of their country that they do not recognize. Allowing CNN, BBC, NPR, and the like onto the Chinese internet is akin to inviting a hostile power into your borders. They know the Chinese state and Chinese media (since 2013 all Chinese journalists are required to be Communist Party members) cannot be counted on to tell the whole truth and Chinese social media is awash in mockery of the heavy-handed, often ham-fisted, censorship. But the desire and ability to hear good news about one’s own country should not be underestimated.

The Chinese economic miracle of the last 30 years, along with a concerted effort by the education system and state media, have left an indelible patriotism stamped onto the soul of the 21st century Chinese. China has gone from a nation suffering regular deprivation—“Have you eaten today?” used to be a common greeting for people on the street—to the second most powerful economy on the planet. Chinese grandparents today remember growing up with emaciated bodies on the street but now obesity is a more common problem than malnutrition. Chinese parents today grew up dreaming of Western technology and now Huawei is a world leader in telecom. “The Chinese expect Baba Beijing to maintain social harmony, political stability and economic prosperity for all.” Says Jeff Brown, a French/American vlogger and Communist author who lived in China for many years, explaining that “the citizens demand and want the Great Firewall.”

The Chinese are proud of China, not just of 5,000 years of history and a globally recognized ancient culture, but of modern China. China the industry leader, China the protector of Chinese business, China the powerful and beautiful and rich. China the unapologetic. This is a story the Chinese want to hear and they don’t care if organizations seemingly determined to only tell the supposedly bad things about China are kept out. And they don’t need the government to fight for their national pride.

#Canceled in China

China’s market is huge. It is the largest online community in the entire world but that is still only a little more than half of their population: over 800 million Chinese people are online regularly out of a country of 1.4 billion. Going viral is relatively easy in China but it doesn’t quite mean the same thing as it does in the West. The scale is different, there are more than twice as many social media users in China (725 million) as there are people in the USA (331 million) and with half their country still not online, this number will continue to grow. The response is different as well, especially for foreigners, as viral content on Chinese social media can quickly draw attention from the media and corporate sponsors, the government, and the wumao.

Given the size of China’s online population, the number of potential cyberstalkers, bullies, and general trolls that can descend on unsuspecting transgressors is staggering. Cyberbullying takes on a new character when literally millions of people are being given explicit encouragement by the state media of the world’s strongest central government. When commentators on China Central Television laud the efforts of wumao to “support and safeguard” Hong Kong from Western lies, this will not curb trolling, doxxing, and harassment—it can only incite more. And victims have no recourse.

The problems for foreign YouTubers began in earnest in 2018, when China launched a dedicated “Report a foreign spy” website. Western YouTubers in—and formerly in—China I contacted for this story recounted multiple instances of mass reporting, culminating in everything from job losses to physical threats to visits from the police.

Georges is a French vlogger who spent 13 years in China and has since moved back to France. He used to run a channel called China Non-Stop, amassing a respectable 15,000 subscribers, but changed his YouTube name to Georges Non-Stop and now says he will make no further videos about China. The wumao made the last year of his life in China awful and the Chinese authorities did all they could to make it hell. Wumao repeatedly spammed his Chinese employers, telling them that Georges had been reported, leading to his termination. Most chilling of all, the police confiscated his passport, telling him it would be returned when he’s “nicer to China.” So he made more “positive content” (proving that sarcasm is not a universal language), got his passport back, and left the country as soon as he could. Georges said in a phone interview that he has since been contacted by at least 10 other foreigners who were all forced to leave China under similar circumstances.

As a consequence of his success on YouTube (the SerpentZA channel has 587,000 subscribers) Winston detailed a deluge of harassment, official and mob-driven, organized against him and his family, in China and even back in South Africa. Instructions on how to report him and his wife were repeatedly posted on Chinese social media [link in Chinese]. His wife, a doctor, was doxxed. Her supervisor and co-workers were doxxed. The Chinese medical board was swarmed with false reports against her and she had to fight to keep her medical license. One day a man showed up at her clinic with a picture of her printed out from a social media post; he had to be physically removed by security. Winston’s family in South Africa were harassed, their neighbors flooded with emails and phone calls explaining how they lived next to racists, placing their lives in danger. The wumao went so far as to target people in South Africa who shared his name but were not, in fact, related to him. This is why he left China.

Richard Vaughn, an American YouTuber who lived in Shanghai for five years vlogging at Triad Travelogues, explained how wumao moles would gain access to private social media group chats on the popular Chinese app WeChat. “They would grab screenshots of private conversations, taken out of context, and post them on nationalist forums and Chinese social media. Leading to more harassment.” These sorts of posts would be used by authorities against Western vloggers as justification for threatening their visa status, employment, or explaining away the harassment as somehow deserved.

Austin Guidry has 22,000 subscribers on Austin in China, a decidedly non-political channel. Four or five years ago he was fired because of some posts he made on YouTube and Facebook that were reported to his employer. Janae Brown was vlogging in China for only one year but even she could recount an instance where she was directly told by her employer to remove a WeChat post. Randy Flagg not only lost a job because of the wumao but, as one of few black men vlogging out of China he also had to see pictures of his biracial family being used in racist memes. Another one of YouTube’s most popular China vloggers knows many stories like this and “knows they’re watching my content,” a sentiment echoed by everybody I contacted for this story: get big enough and the government will be monitoring you—say the wrong thing and the wumao will attack.

“I love China,” said every China-based YouTuber interviewed for this story. The community of Western YouTubers in China is a vibrant and generally very China-positive place. Most of the YouTubers know each other and act like most communities do, supporting each other’s efforts, sharing tips and techniques, and enjoying each other’s company.

I asked how they manage to stay ahead of the censors. “Why would I need to?” said an American YouTuber in Guongdong. “My videos are about my students and neighbors and the places in China I visit.” Matthew Galat, long-time China YouTuber with over 56,000 subscribers, echoed many of his fellow YouTubers, “It’s all about how you dance around issues. There’s enough negative stuff out there. I talk positive about China.” Another American vlogger, a military veteran, put it quite plainly, “This isn’t my country. They didn’t ask me to come. If they don’t want me to talk about certain things, I don’t.” Another long-term vlogger bluntly said in an email that, “The man that DOES NOT censor himself in China doesn’t stay in China long.”

Over WeChat, I asked a number of China vloggers whether or not the community members share any tips with each other on how to skirt the censors or avoid agitating the wumao. “It’s something you learn quickly enough.” Says Adam Crase of the Kung Fu Imaging channel, “There’s no reason to ask what you can’t say because anyone informed enough to be making videos about China should know already.”

“Considering the capriciousness, and humorlessness, of the Chinese Communist Party aren’t you worried that you may end up on the other side of the Great Firewall?” I asked. After all, Winnie the Pooh and basketball ended up being politically sensitive practically overnight. A few vloggers, all under condition of anonymity, expressed concern about the arbitrary unpredictability of Chinese censors. “Honestly, it’s always in the back of my mind,” said one relatively popular American YouTuber in a Skype interview, “that one day they’ll just ask me to leave for doing nothing differently than I did the day before.”