Health

Why I Resigned from Tavistock: Trans-Identified Children Need Therapy, Not Just 'Affirmation' and Drugs

Separation from the mother is an important part of the infant’s psychological development.

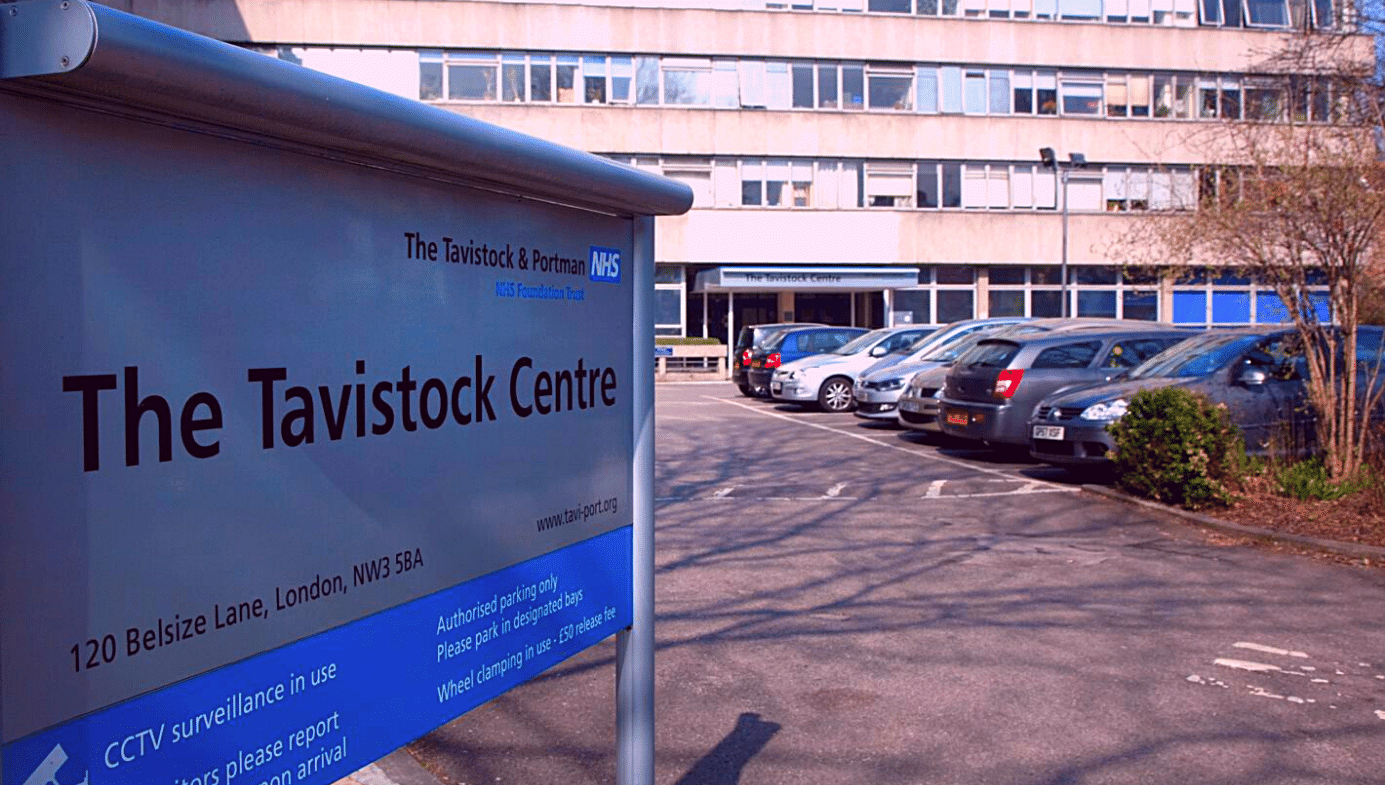

Over the past five years, there has been a 400 percent rise in referrals to the Tavistock Centre in north London, the only National Health Service (NHS) clinic in Britain that treats children with gender-identity developmental issues. During this period, there also has been an abrupt shift in the composition of the children seeking treatment. Formerly, a significant majority of patients had been young male-to-female children. Now, a significant majority are biological females who claim to have a male gender identity, often following the rapid onset of gender dysphoria in their teenage years.

We do not fully understand what is going on in this complex area, and it is essential to examine the phenomenon systematically and objectively. But this has become difficult in the current environment, as debate is continually being closed down amidst accusations of transphobia. As I argued in a May, 2019 presentation before the House of Lords, this de facto censorship regime is harming children.

Those who advocate an unquestioning “affirmation”-based approach to trans-identified children often will claim that any delay or hesitation in assisting a child’s desired gender transition may cause irreparable psychological harm, and possibly even lead to suicide. They also typically will cite research purporting to prove that a child who transitions can expect higher levels of psychological health and life satisfaction. None of these claims align substantially with any robust data or studies in this area. Nor do they align with the cases I have encountered over decades as a psychotherapist.

During the 1980s, I assessed adult parasuicides (apparent suicide attempts, or suicidal gestures). A number of my patients had gone through gender-reassignment surgery, and often were angry at the loss of their biological sexual functioning. They also were aggrieved with psychiatric professionals, who, they believed, had failed to adequately investigate the underlying psychological difficulties associated with gender dysphoria.

As a psychotherapist, I consulted with various mental health services that managed patients exhibiting challenging behaviours. In this capacity, I observed that patients who had a history of serious and enduring mental illness or personality disorder sometimes would also develop gender dysphoria. A common theme in their presentations was the belief that physical treatments would remove or resolve aspects of themselves that caused them psychic pain. When such medical interventions failed to remove their psychological problems, the disappointment could lead to an escalation of self-harm and suicidal ideation, as resentment and hatred toward themselves was acted out in relation to their bodies.

One young man, who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, had a fear of his own aggression, as he had once threatened his mother (whom he relied upon to care for him) with a weapon. After I treated him for several months, during which time he explored his fear of his own explosive temper, he suddenly announced that he wanted to change sex. There had been no previous evidence of gender dysphoria mentioned either in his notes or in his consultations with me.

At that time, schizophrenia was a negative indication for sexual-reassignment surgery. However, the patient was quickly assessed and taken on by Charing Cross Gender Identity Clinic. In my opinion, switching gender likely was a strategy for immobilizing his frightening temper and fear of psychotic outbursts (as women are stereotypically less violent and threatening). I wrote to Charing Cross recommending that the psychotherapy should be allowed to continue, and that the gender-reassignment treatments be put on hold, so that these deeper issues could be addressed. The team treating the patient indicated their disagreement and continued with the referral.

My concerns in this field became more acute in Spring, 2018, after I retired from active work as a therapist and joined the Board of Governors of The Tavistock and Portman NHS, which hosts the National Health Service’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the aforementioned Tavistock Clinic—a public facility available to everyone in the UK. Almost as soon as I’d joined, I was made aware of the growing controversy over GIDS. A letter had come in from a group of parents complaining that their children had been fast-tracked through GIDS without any serious psychological evaluation. The author of the letter, a mother representing a group of parents, wrote to me in my role as governor, and I replied, circulating copies of that reply to other governors.

Around the same time, Dr. David Bell, a senior consultant at the Tavistock & Portman NHS Trust and a Tavistock governor, was approached by 10 GIDS staff members (amounting to about one-fifth of the London-based service) who had grave ethical concerns similar to those expressed in the parents’ letter—including inadequate clinical assessments, patients being pushed through for early medical interventions, and GIDS’ failure to stand up to pressure from trans activists. As I discovered, this was not the first time such concerns had been raised. Thirteen years previously, psychotherapist Susan Evans (who, full disclosure, is my wife) had raised her own concerns about the thoroughness of the assessment process by some staff.

As a governor of the Tavistock Trust, I personally witnessed attempts by the Trust’s management to dismiss or undermine both Dr. Bell’s report, which he submitted in late 2018, and the letter from parents. This included accusing Dr. Bell of fictionalizing the case studies he described, questioning his credentials, withholding his report from certain governors, and preventing him from attending a meeting to discuss the Medical Director’s response to his report.

I have learned, through long experience with managing clinical areas in the National Health Service, that such efforts to dismiss or discredit serious concerns about a service or clinical approach typically are driven by those seeking to evade accountability and shield their methods from criticism. Such a defensive, self-serving approach would be dangerous and objectionable in any NHS context. It was particularly worrying in the context of a service that treats vulnerable young people in the midst of life-changing, often irreversible decisions that have unknown medical consequences. And so in 2019, I resigned from the Tavistock board of governors, in protest over the Trust’s failure to address the serious concerns that Dr. Bell and parents had raised.

Many mental-health professionals share these concerns. But saying so publicly is difficult. Journalists who have researched this area report that while interviewees are willing to speak in confidence about their concerns, they shy away from being named, for fear of being accused of bigotry or taken up on human-rights claims. In an excellent 2019 book, Inventing Transgender Children and Young People, authors Heath Brunskell-Evans and Michelle Moore brought together a mix of experienced clinicians and academics to critique certain approaches to gender dysphoria. In an extraordinary step, GIDS threatened legal action against the publisher, and demanded to see the book before publication.

What’s worse, the effort to suppress unfashionable views has been joined by some leading organizations, including the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP), whose policy statement on the issue, Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents, was scathingly debunked in a recently published peer-reviewed journal article by James Cantor. “Although almost all clinics and professional associations in the world use what’s called the watchful waiting approach to helping gender-diverse (GD) children, the AAP statement instead rejected that consensus, endorsing gender affirmation as the only acceptable approach,” Cantor writes. The AAP’s approach, like that implemented by many clinicians at GIDS, appears to be driven more by political ideology than the clinical needs of presenting children.

In part, this trend is rooted in the faddish idea that everyone—including children—has an innate gender identity, akin to a religious soul, that one discovers and nurtures. But as authors William J. Malone, Colin M. Wright and Julia D. Robertson recently wrote in Quillette, the concept of gender identity is dubious:

This term commonly is defined to mean the “internal, deeply held” sense of whether one is a man or a woman (or, in the case of children, a boy or a girl), both, or neither. It also has become common to claim that this sense of identity may be reliably articulated by children as young as three years old. While these claims about gender identity did not attract systematic scrutiny at first, they now have become the subject of criticism from a growing number of scientists, philosophers and health workers. Developmental studies show that young children have only a superficial understanding of sex and gender (at best). For instance, up until age seven, many children often believe that if a boy puts on a dress, he becomes a girl. This gives us reason to doubt whether a coherent concept of gender identity exists at all in young children. To such extent as any such identity may exist, the concept relies on stereotypes that encourage the conflation of gender with sex.

It is certainly true that therapists shouldn’t seek to impose their idea of what is “normal” on a patient who believes he or she is trans. Nor should they engage in an attempt to convert the individual to their way of thinking. However, as in all contexts, the therapist must resist the temptation to suspend curiosity, uncritically accept the patient’s presentation at face value, and then act as an “affirming” cheerleader for life-changing acts of transition. Rather, the goal of exploratory therapy should be to understand the meaning behind a patient’s presentation in order to help them develop an understanding of themselves, including the desires and conflicts that drive their identity and choices.

To some extent, the extreme deference now being shown to trans-presenting children may be linked to the more general change in the way doctors and other authority figures are perceived in the internet era. While such authority figures once had broad licence to evaluate their patients according to their expertise, such “gatekeeping” is now seen as controlling and even repressive. Many patients now see a doctor’s visit through the lens of consumer culture—whereby the customer is always right.

When doctors always give patients what they want (or think they want), the fallout can be disastrous, as we have seen with the opioid crisis. And there is every possibility that the inappropriate medical treatment of children with gender dysphoria may follow a similar path. Practitioners understandably want to protect their patients from psychic pain. But quick fixes based only on self-reporting can have tragic long-term consequences. And already, a growing number of trans “desistors” (also known as detransitioners) are seeking accountability from the medical professionals who’d rubber-stamped their trans claims. And in 2019, when a formerly trans-identified British woman named Charlie Evans went public with her desistance, she was contacted by “hundreds” of other desistors, and formed a group called The Detransition Advocacy Network to give them a voice and support in a contentious environment that has been dominated by dogmatic trans ideology.

In the NHS, clinicians typically are legally required to discuss the serious negative effects of any offered treatment. As in so many other ways, however, the issue of gender dysphoria seems to lie outside the usual rules that govern medical practice. Many involved in this field have commented on the peculiar fact that, despite the extraordinary preoccupation with the abstraction of gender that suffuses this area, there is little discussion about the flesh-and-blood reality of sex and reproduction.

A clinician interviewed by the Times of London reported being discouraged from even asking patients about these issues: “I would ask who they wanted to have relationships with, but I was told by senior management that gender is completely separate to sex.” Yet part of the developmental struggle in adolescence requires us to come to terms with the reality of who we are, including our natal sexuality and the different roles demanded of us in reproduction. There are all sorts of anxieties attached to these activities and the functioning of the body—anxieties that may be so severe as to distort our sense of self. As Dr. Cantor has noted, the available studies show that most pre-adolescent children who present as trans eventually revert to an identity that accords with their biological sex. Yet many of these children (and their parents) seem to receive little information about how their lives will be affected if they proceed with transition. In the words of one young woman who went through this: “Lots of talk about gender politics and none about the physical realities involved in transitioning.”

With minors, informed consent for medical treatment generally may be expressed by parents. But these decisions usually are taken when a child has a life-threatening physical illness or requires surgery. Relying on informed consent in regard to gender-based medical interventions with life-long consequences, when no one can be certain what the child will think in 10 years’ time, is more questionable. The whole idea of treating gender dysphoria medically is to shift the focus of the problem from the mind into the body. But while beliefs may change, the effects of such medical interventions may be irreversible.

It is striking to observe how certain members of the pro-affirmation lobby seem to be about their approach, despite a lack of high-quality data. And much of the data that does exist fails to support their claims. A 2011 study, for instance, found that “persons with transsexualism, after sex reassignment, have considerably higher risks for mortality, suicidal behaviour, and psychiatric morbidity than the general population.” And while a 2018 paper studying the impact of hormone blockers concluded that “low-quality evidence suggests that hormonal treatments for transgender adolescents can achieve their intended physical effects,” the authors also found that “evidence regarding their psychosocial and cognitive impact are generally lacking.”

In 2016, the U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services reviewed the long-term outcome studies of sex-reassignment surgery. Of the 33 studies reviewed, most were found to have methodological problems that rendered their conclusions unreliable. And the studies deemed reliable failed to show substantial improvements in psychological functioning after gender-reassignment surgery—despite the fact that anecdotal evidence suggests a strong bias toward the funding and publication of studies that align with affirmation-based approaches (and a countervailing effort to bury data that fails to support such methods).

In fact, several studies have been closed down prematurely following expressed opposition from pro-trans lobby groups and their media allies. In 2017, Spa University denied the extension of research being performed by psychotherapist James Caspian into patients seeking to reverse the effects of gender-reassignment surgery. “The fundamental reason given,” he said, “was that it might cause criticism of the research on social media, and criticism of the research would be criticism of the university, and they also added it was better not to offend people.”

Kenneth Zucker, a well-known researcher and clinical lead at the Child Youth and Family Gender Identity Clinic in Toronto, was sacked outright in 2015 after being accused of conducting “conversion therapy” by trans activists. The claims proved baseless, and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, his employer, agreed to pay Dr. Zucker $586,000 as part of a legal settlement (and apologized “without reservation” for the treatment he’d received). A subsequent investigation completely exonerated Prof. Zucker, and it became clear that the activists demanding his removal were simply angry that he helped children come to terms with their biology before proceeding to transition (this is the so-called “watchful waiting” process, which most responsible clinicians use around the world).

In his report to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust Board, Dr. Bell cited the high percentage of patients suffering from gender dysphoria who also suffer other complex problems, such as trauma, autism, a history of sexual abuse and attention deficit disorder. This finding is consistent with a growing body of knowledge that connects the development of gender dysphoria with psychological factors. Since resigning my position at Tavistock, I’ve been contacted by many parents asking advice about trans-identifying children who often tend to exhibit one or more of these factors. Typically, the parents were concerned that services such as Tavistock encouraged the idea that their child’s problems could be comprehensively addressed merely by changing gender.

They also would express concern that their child was being groomed by a thicket of online video resources that instruct children on how to get past whatever nominal clinical gatekeeping they may encounter. An increasingly common characteristic of children presenting with gender dysphoria is a deep involvement within online chat groups that support their sense of dislocation, encourage them to view voices of moderation (including parents) as enemies, and which echo the cultish language of pro-anorexia and pro-suicide websites. As in actual cults, followers are encouraged to believe that their entire gamut of personal problems can be solved so long as they embrace one overarching dogma. “Feel dislocated from your sex, feel like you do not fit in?” asks the Transgender Heaven website. “Here is a group that understands your feelings of dislocation and confusion and can offer you an identity that can provide certainty and a feeling that you belong.” Or as one pro-trans vlogger said on YouTube, “trans is a solution to feeling shit.”

“My online experience, having been affected by that level of groupthink, that level of moral policing, and the constant implicit threats of social exposure and [ostracism] made me an intensely internal and anxious person,” reported one detransitioned woman about her online experience in this world. “It made me paranoid about the motives of people around me—I saw my parents as bigots because tumblr told me to; because they held out for so long to prevent me from starting hormones. Anyone that slipped up and misgendered me was, according to tumblr, an enemy. One incident—one ‘she’—had the ability to make me absolutely hate someone. Tumblr’s version of morality and justice made me—an impressionable, insecure teenager—feel like my only safe place was in my head, where I would never be misgendered.”

Influential British psychoanalyst Roger Earlie Money-Kyrle once described the difficulty we all have in coming to terms with three distinct realities traditionally associated with the facts of life: (1) our dependence on our mothers in infancy, (2) the difference between the sexes, and (3) the difference between the generations. Taken together, these realities present us with painful truths about our dependence on others, our own personal limitations, and our mortality. Even those of us who believe we are well-adjusted and happy often find ourselves unconsciously defending against the full implications of these realities.

In some cases, these defence mechanisms can cause us to radically change the way we present to the world. But maturity and psychological growth require us to face, rather than avoid or misrepresent, the reality of who we are and who we are not. Mechanisms designed to deny or distort reality can harm us by preventing emotional development. And so it makes sense to understand our relationship to sex and its expression in the context of our struggle with these realities, rather than treating gender as a completely separate issue detached from biological reality.

Infants typically rely on an attentive maternal figure in order to bring them into the world and care for them. This (hopefully) loving and caring relationship provides a bedrock for an infant’s developing mind and sense of him/herself. Influential paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott described the mother’s relationship with the infant at this stage as primary maternal preoccupation. The spell of the maternal preoccupation is broken when reality impinges in the form of weaning, and the mother goes back to work or has another baby.

Separation from the mother is an important part of the infant’s psychological development. However, the psychological and physical separation can be experienced as trauma. This in turn can lead to either a wish to possess the mother in some way, or a grievance toward the mother, as the infant finds it hard to give up the ideal relationship represented by the primary maternal preoccupation. In a recent paper entitled Time and the Garden of Eden Illusion, psychoanalyst John Steiner describes the common fantasy of returning to an imaginary, idealized relationship with one’s mother. This fantasy often is connected, more generally, with an idealized time, place or relationship in the patient’s life before that life became more complicated or upsetting.

Basic biological realities and differences between sexes can provoke intense feelings of exclusion in some members of the trans community. Every person is different, but some individuals seem to believe that they have been traumatically excluded from their rightful female gender, and so any attempt by natal women to exclude them is experienced as a psychological attack (as evidenced by their sometimes shockingly intense expressions of anger at biological women).

I believe that this sensitivity to exclusion from female spaces is sometimes related to unconscious anxieties and grievances associated with traumatic separation from the primary carer. This helps explain why some members of the trans community act as if their psychological wellbeing hinges on their right to enter any female space whatsoever, even though biological women can feel this to be intrusive and threatening.

American-Canadian sexologist Ray Blanchard coined the term autogynephilia to describe a male’s propensity to be sexually aroused by the thought of himself as a female. But even in cases where such sexualized impulses are absent, a trans woman may be impelled by a desire to establish a self-embodied replacement for a mother (or mother figure). In my clinical experience, such forceful psychological defences dominate the mind, and thereby make it difficult for the person to consider alternative views or underlying psychological structures.

In parallel with these attachment issues, children also are presented with the reality associated with their biological limitations as boys or girls. This can provoke fixations or rivalrous feelings in regard to the other sex. As part of normal development, the child experiments with different ways of expressing their sexuality and relating to the opposite sex. A boy has to come to terms with the fact that he has a penis and that he eventually will have to penetrate a woman to create a baby. A girl has to allow herself to be penetrated if she wants a child. The anxiety caused by these different sexual roles and their different requirements may cause extreme distress or anxiety, which then leads to a denial of sexuality. (When one child I know was told how babies were made, he replied that it was disgusting and that people could get hurt.) The physical difference between the sexes may be experienced as so traumatic that it leads to an attempt to deny sexual differences altogether, as men may envy women their reproductive capacities while women may envy a man’s potency and perceived power in the world. It’s a universal human phenomenon that we all have to wrestle with and resolve.

This may help explain the curious insistence by some trans women that their biologically male bodies offer them no competitive advantage in sports; or that their male bodies and sexual anatomy should not be seen as threatening to women in vulnerable spaces such as locker rooms and rape-crisis centers. Such delusions, in turn, have encouraged a sprawling academic ecosystem of self-described gender specialists who insist that the very idea of separating humanity into male and female—the basis of sexual reproduction, and therefore the survival of our species—somehow relies on an artificial construct.

To repeat: Every case is different, and people may come to their trans self-identity in all sorts of ways. The extraordinarily complex nature of their condition means that gender dysphoric young people, in particular, need access to independent clinicians who protect the long-term interests of their patients, rather than use their patients to advance an ideological agenda.

This requires clinicians to maintain an arm’s-length distance from activists, in order that they may perform truly independent assessments. Unfortunately, Dr. Bell’s report quoted several staff to the effect that management at Tavistock’s GIDS service seemed to have succumbed to activist pressure. And an article in the Times described five former Tavistock staff members who believed that “transgender charities such as Mermaids were having a ‘harmful’ effect by allegedly promoting transition as a cure-all solution for confused adolescents.” This is obviously problematic.

A proper assessment process involves two parts. Firstly, an extended psychotherapeutic approach should be used to assess and attempt to understand the meaning of the patient’s presentation. Importantly, this includes an understanding of the family and social context in which any disorder emerged. Further, it involves an appreciation of the less conscious factors that underlie gender identity. This difficult psychological work can feel threatening, as it often challenges an individual’s often strongly held conviction that only a change in sexual identity can bring relief to their problems.

Secondly, the assessment should examine the issue of informed consent, and include a full discussion about the losses and risks involved in any active intervention that could compromise biological functioning. The question of how informed the individual is regarding the implications of the medical intervention should be seen as a crucial indicator. For example, if the individual has no concern at all about the prospect and outcomes, this lack of concern should be classified of as a symptom that needs to be investigated, rather than simply a positive indication of the patient’s motivation.

We also should remember that patients presenting with symptoms of gender dysphoria often are dissociated from their natal body, which they feel contains unwanted or unacceptable parts of the self. The fantasy that the individual can sculpt the body according to his/her wishes adds (temporarily) to the sense of power and control over the body and everything contained within it. This has similarities with body dysmorphia, a condition whereby the individual becomes obsessed with a physical flaw. Such individuals often seek cosmetic surgery with the belief that their problems will be solved if the flaw is removed. But in the case of gender dysphoria, medical intervention cannot completely eradicate the reality of a patient’s natal gender. This can lead to a sense of persecution, as the body offers a reminder of the continued existence of an unwanted aspect of the self.

This sense of persecution sometimes leads to self-hatred, which can turn into suicidal ideation. At other times, the hatred is externalized, and the individual begins to feel they are surrounded by people who question the validity of their claim to be their chosen gender. It is evident that aggressive elements of the pro-trans group are embarking on a campaign designed to threaten all those who withhold such affirmation. It is as if they believe they can cure their own internal doubts about the validity of their gender claims if they can control the views of others, which helps explain the extreme feelings of trauma they experience when they believe they have been misgendered.

This battle over perception has started to influence the legal system in the UK and other countries that use self-identification as a legal basis for classification. And referring to biological sex rather than gender now can be categorised as a hate crime rather than an expression that is factually correct.

I am asked for advice by some parents whose children suddenly announce they are gender dysphoric. Some tell me that they do not trust the gender care offered by their local health provider. I tell them that any hint that clinicians are pushing the child down a narrow, one-size-fits-all diagnostic and treatment program should be seen as a red flag. But this is difficult, because affirmation-based approaches are being adopted by children’s mental health services.

“First do no harm,” should be the least we expect from those who treat our children. Yet in 2019, it was revealed that the GIDS program at Tavistock clinic had lowered the age at which it offers children puberty blockers on the basis of a study that—it later was revealed—concluded that “after a year of treatment, ‘a significant increase’ was found in patients who had been born female self-reporting to staff that they ‘deliberately try to hurt or kill myself.’” The fact that Tavistock officials ignored such evidence suggests they have bought into the idea that transition is a goal unto itself, separate from the wellbeing of individual children, who now are being used as pawns in an ideological campaign.

This is the opposite of responsible and caring therapeutic work, which is based on the need to re-establish respectful but loving bonds between mind and body. Such are the norms in every other area of therapeutic practice. And it is high time that the ideologues who have hijacked therapy’s gender subculture be held to account.