recent

Chile’s Been Falling Apart for Years. Can It Repair Itself and Remain a Democracy?

Chilean middle class has seen its fortunes becomes more precarious, with many families staying afloat only through borrowing.

“In Chile, a billionaire president pushes austerity while the military represses protesters,” Tweeted U.S. Senator and Democratic presidential aspirant Bernie Sanders on October 30. “Thousands have been arrested. Knowing Chile’s history, this is very dangerous. The solution here and across the world is obvious. Put power where it belongs: with working people.” The next day, Donald Trump’s White House put out a statement containing the opposite message: “The United States stands with Chile, an important ally, as it works to peacefully restore national order. President Trump denounced foreign efforts to undermine Chilean institutions, democracy, or society.”

Needless to say, both statements vastly simplify the situation in Chile, a country that still is used as a proxy battle for old-fashioned arguments for and against “neo-liberalism.” Like Sanders, some media outlets suggest that the current protests in Chile may be construed as toxic fallout from the free-market legacy of right-wing dictator Augusto Pinochet. On the other side are those such as City Journal writer Guy Sorman, who see the protests not as an indictment of free-market policies, but as a symptom of their incomplete implementation.

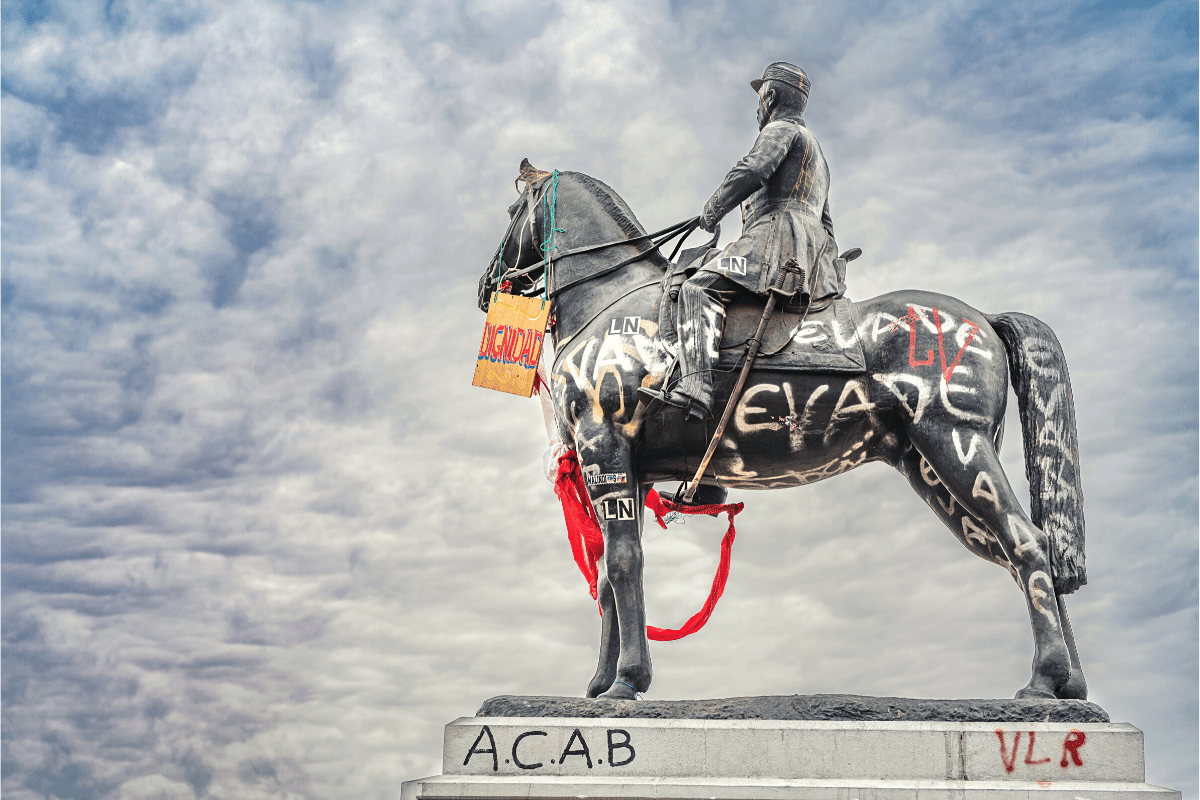

The protests began when students began a mass-transit fare-dodging campaign following the government’s announcement of fare hikes. The police have reacted with violence in some cases, and at least 20 lives have been lost. As of this writing, in the capital city of Santiago alone, the riots have caused US$1.6-billion in economic damage. Subway stations have been destroyed, and close to a third of the country’s supermarkets have been vandalized. Ironically, the effect of these protests in the name of ordinary people is that workers from Santiago’s poorer districts now have more difficulty getting to work, and family-owned businesses that depend on a steady flow of foot traffic have been hard hit. The government has been forced to cancel two high-profile international summits. The damage to Chile’s reputation and national prestige have been immense.

The fare hike was obviously only the tip of a larger economic iceberg. The level of income inequality in Chile is among the highest in the developed world. And the sense that ordinary people are shut out of the country’s leadership and wealth permeates public life. As Javier Sajuria recently wrote in the Washington Post, “most elected representatives come from a closed and small elite who are living in a far more privileged reality than the rest of the country…A United Nations Development Program report in 2017 showed inequalities in almost every aspect of public life, including access to health care and such services as pharmacies, police provisions and public transportation. Moreover, a recent study showed that studying in select Chilean private schools and being male are the strongest predictors of reaching top executive jobs in the country.”

In recent years, the Chilean middle class has seen its fortunes becomes more precarious, with many families staying afloat only through borrowing. Household debt as a percentage of GDP is now almost 45% in Chile, far higher than in other large South American nations. The causes are similar to those everywhere: rising housing prices, wage stagnation and a steady rise in the price of necessities such as water and heat. Middle-class families have been forced to cope with the costs associated with the country’s retiring “Boomer” generation and its meager pension earnings. The economic burden of caring for these elderly Chileans has fallen on their already burdened relatives.

Notorious cases of corruption and white-collar crime regularly dominate the news, which has contributed to a loss of trust in all forms of authority. An unintended effect of political reforms has been that successive Presidents have ruled without real majorities, and many people don’t feel like their vote counts for much. The current President, Sebastián Piñera, is a Harvard graduate whose net worth is almost US$3-billion. A sense of nihilism seems to animate many of the protestors, who know that something is rotten, but can’t articulate what it is—and so their anger is expressed with angry gestures that primarily inconvenience other marginalized citizens.

If the looting, arson and violence have had any upside, it is that they have made visible the existence of formerly ignored marginal groups. Adapting the Marxist term “lumpenproletariat,” opinion leaders sometimes refer to these groups as “the lumpen,” which is connected in the public imagination principally to two Chilean institutions: prisons and the Servicio Nacional de Menores (known as “Sename”), whose mission is to care for minors at risk. Both institutions have been almost totally abandoned by the state during the last 30 years. Prisons are operating at twice their original intended capacity. And a report released in 2018 found that about 1,300 children who were supposedly under the protection of the Sename died between 2005 and 2016. (Pedophile organizations have long been known to target the institutional shelters.) Public intellectuals in Chile on both right and the left have been issuing warnings for many years about how this fraying social safety net would one day lead to unrest. The phrase one often sees at the protests, Chile despertó (“Chile woke up”), speaks to a country that is opening its eyes to problems that everyone always knew were there.

“Neo-liberalism was born in Chile, and here it will die,” is a demand you see on some of the placards—words that echo age-old left-right doctrinal arguments about the role of the state in helping its citizens. But alongside these grand slogans are a multitude of radically individualized messages, tagging distinctive causes, from pensions to transport costs to college tuition. Many seem convinced that it is possible to finance all of these causes only by taxing the rich. (Even some very rich people make this argument, on the understanding that they are speaking of the super-rich—which is to say, people richer than themselves.) Yet it’s hard to see anything emerging from this movement that isn’t some reformulation of the current corporate-friendly “neo-liberal” order that protestors say they detest. The present age, Kierkegaard once wrote, momentarily bursts into enthusiasm, and then shrewdly relapses into repose. That repose might only be avoided with the renewal of committed, grass-roots forms of civil society that become centers of political gravity in Chile.

Many educated and bourgeois figures on the left are seeking a “constitutional assembly” that would replace the Pinochet-era constitution in a way that emphasizes social welfare and the rights of citizens to participate in the political process. On the other side of the spectrum, many conservatives worry that a new constitution would simply become a catalog of social rights that encourage false expectations, and thereby sow the seeds for ever more unrest. Others are looking for fixes to the procedures of Chilean democracy, including a proposal to bring back Chile’s former mandatory-voting system, and thereby solve the problem of centrist voter apathy by decree.

A common fear is that the country will simply drift toward authoritarian populism in its left- or right-wing versions, a pattern that has played out often in the history of this region. When this happens, the common ingredients tend to be public disaffection, a scapegoating style of politics, and the false hope that ordinary citizens may be delivered from the dominance of a rich and powerful elite simply by ceding all power to a charismatic strongman who himself is plucked from among the ranks of that same elite.

The other option is the fostering of a spirt of civic responsibility. That would require long-term political commitment from citizens, the creation and nourishment of new forms of civil society, and the understanding that reforms take time, and so it is necessary in the interim to prioritize the assistance of those who are worst off.

Democracy requires both leaders and voters to exist in a permanent state of anticipation and reform. When they shirk that responsibility, history has a way of waking them up. This is what is now happening in the streets of Santiago.