History

Frederick Douglass, The Columbian Orator, and the 1619 Project

This vision of universal human rights based on our common humanity was the common ground shared by these two antislavery giants in American history, and it is the common ground now renounced by the 1619 Project.

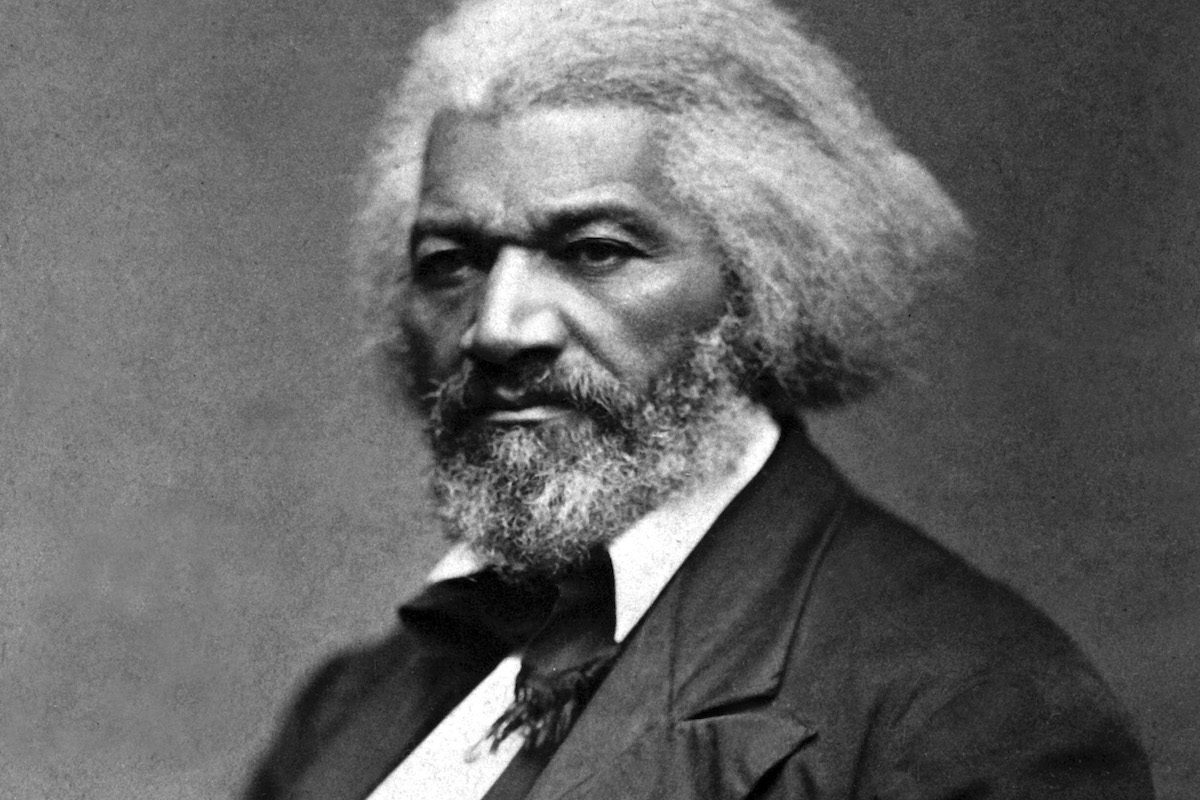

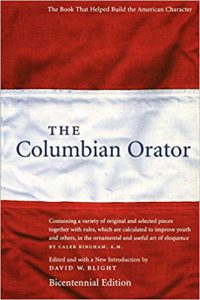

On September 3, 1838, the most famous slave in American history began his escape to freedom. Dressed as a free black sailor and equipped with forged identification papers, Frederick Douglass fled Maryland. Remarkably, this fugitive carried with him a book, which was perhaps his sole possession: The Columbian Orator.

In his three autobiographies, written over the five decades of a very public life, Douglass consistently paid tribute to The Columbian Orator. He describes the book as an intellectual turning point that liberated him from the mental shackles of slavery. Indeed, the connection between slavery of the mind and slavery of the body is a recurrent theme in Douglass’s political thought. In his autobiographical Narrative (1845), he explains:

I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceases to be a man.

Thus, reading and education were the first steps in his journey to freedom. Considered a quick learner by his Baltimore owner Lucrezia Auld, who taught him his ABCs, the lessons abruptly stopped when Thomas Auld discovered that his wife was teaching their slave, something strictly prohibited at the time. But Douglass developed creative stratagems to learn to read and write, including trading bread to “poor white boys” in exchange for lessons. His remarkable account of his early self-education in these autobiographies includes a touching report of his companions’ universal sympathy to his plight as a slave. He states that he did not “remember to have met with a boy…who defended the slave system; but I have often had boys to console me, with the hope that something would yet occur, by which I might be made free. Over and over again, they have told me, that they believed I had as good a right to be free as they had….” Contrary to our current obsession with racial consciousness, he never considered that these young boys, being white, cannot understand him, nor does he doubt their sincerity.

After hearing some “little boys,” perhaps some of the “hungry little urchins” who taught him to read, reciting pieces from The Columbian Orator, Douglass purchased a copy of the book for fifty hard-earned cents. He studied it closely. He was most moved by a fictional dialogue in the book between a master and slave who had been recaptured after three attempted escapes. The master upbraids him for ingratitude, claiming that he had generously provided all of life’s necessities. The slave is then allowed to speak freely in response, and effectively refutes all of the master’s arguments. In his second autobiography, My Bondage, My Freedom, Douglass observed that, “The master was vanquished at every turn in the argument; and seeing himself to be thus vanquished, he generously and meekly emancipates the slave, with his best wishes for his prosperity.” Recalling his first foiled escape attempt, Douglass again mentioned the inspiration of The Columbian Orator: “That…gem of a book….with its eloquent orations and spicy dialogues, denouncing oppression and slavery—telling of what had been dared, done and suffered by men, to obtain the inestimable boon of liberty—was still fresh in my memory.”

The Columbian Orator was a collection of political writings, published in 1797, and edited by Caleb Bingham, a devout Congregationalist, New England educational reformer, and valedictorian at Dartmouth. Politically, Bingham was a Jeffersonian in a Federalist region. As clearly reflected in his book, he shared his party’s enthusiasm for the French Revolution and the universal rights of man. He displayed a life-long sympathy to Native Americans and opened the first private school for women in Boston. In its time, The Columbian Orator was so popular that it went through 23 editions. Consisting of 84 short selections of inspiring political speeches, poems, and dialogues, it included such diverse authors as Socrates, Philo, John Milton, Cicero, Benjamin Franklin, and George Washington. Though supportive of the ideals of the French Revolution, it also included British statesmen who were sympathetic to the colonies and the cause of human rights, some of whom made a lasting impression on Douglass. Its pedagogical intent was to prepare the youth of the revolutionary generation for the responsibilities of republican citizenship. In so doing, it united a concern for both elocution style and moral substance. Its ethical, religious, and political teachings drew upon four great traditions that Bingham believed had shaped the American mind: Enlightenment rationalism, Greco-Roman republicanism, British constitutionalism, and protestant Christianity.

The historian David Blight, who was recently awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his outstanding biography of Frederick Douglass, sums up the legacy of The Columbian Orator as “more than a collection of stiff Christian moralisms for America’s youth. It was the creation of a school reformer of decidedly antislavery sympathies, a man determined to democratize education and instill in America’s youth the immediate heritage of the American Revolution the habits and structures of republicanism.” And historian John Stauffer notes in his book Giants—The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln that it “was one of two books that started Douglass on his journey to eloquence and freedom…. The other book was the King James Bible.” Given its antislavery message, The Columbian Orator was placed on a blacklist of abolitionist works and banned by prominent southern newspapers during the sectional crisis of the 1850s.

What The Columbian Orator reminds us, and what Douglass himself passionately argued over a lifetime of advocacy, is that the United States was a nation with a complex history, that it was based on great ideals that it had failed to live up to. This is quite the opposite of the view presented in New York Times’ 1619 Project, the stated goal of which is “to reframe American history, making explicit how slavery is the foundation on which this country is built.” According to the Times, such reframing is necessary since slavery “grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional.” The very title of the project comes from the Times’ extraordinary claim that 1619—the date that the first Africans were brought to Virginia—should replace 1776 as the symbolic birth of the American experiment. Emblazoned in bold print on the first page of the lead article is the cynical declaration that, “Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written.” This brash assertion confuses the important distinction between principle and practice made by Douglass and many of the Founders themselves. On the contrary, as confirmed by The Columbian Orator and Douglass’s own testimony, there were significant antislavery voices in America who hoped to close the gap between the ideal of equality and the reality of slavery. The struggle for equality would nonetheless continue, leading ultimately to the Civil War and the cost of over 700,000 American lives.

As Andrew Sullivan has aptly noted, the Times has exchanged news reporting for political activism. Its message is that the stated ideals of the United States were never sincere, but were just a cover for racism—and that such structural racism and insincerity continues today. To propagate its message, the Times offers resources, websites, and links for teachers to re-educate impressionable students about a Manichean racial struggle that has no foreseeable end. In this narrative, all whites were oppressors or complicit in oppression and the stated principles of the Revolution were a mask to conceal the operations of naked power.

This re-framing of American history by the 1619 Project is not entirely new. Ironically, the Times is uncritically repeating Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s opinion in the infamous case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, 1857. Surveying the American Founding, Taney similarly concluded that blacks “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” Taney’s pro-slavery narrative, repudiated by Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Republican Party at the time, often reads like contemporary critical race theory: “This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals treated as well as in politics which no one thought of disputing or supposed to be open to dispute, and men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted… without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.” But as the popularity of The Columbian Orator and as Douglass’s experience both make clear, Taney was not reporting “fixed and universal” opinions.

For Douglass, the struggle for equality and human rights transcended racial lines. Given his view of our common humanity, he extolled the speeches of British and Irish statesmen found in The Columbian Orator for helping to articulate and support the cause of liberty. In particular, he lauded the efforts for Irish emancipation, because they contained “a bold and powerful denunciation of oppression, and a most brilliant vindication of the rights of man.” These speeches, he confesses, were “choice documents to me. I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance.” Douglass has no notion like the contemporary one of “whiteness,” which reduces all thinking to racial struggle. Nor does he worry about “cultural appropriation” in his appeal to western ideals. On the contrary, he considered the British and Irish statesmen as fellow travelers in the cause of universal human rights. Appealing to our common humanity rather than particular racial consciousness, he confessed: “The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder. What I got from Sheridan was a bold denunciation of slavery and a powerful vindication of human rights.”

While prophetically rebuking America for its hypocrisy in failing to live up to its stated ideals, the mature Frederick Douglass nonetheless struggled mightily to distinguish between principle and practice in American politics. Repudiating the proslavery re-interpretation of the Constitution advanced by Taney and southern Fire-Eaters, on March 26, 1860 he stated:

[T]he constitutionality of slavery can be made out only by disregarding the plain and common sense reading of the Constitution itself; by discrediting and casting away as worthless the most beneficent rules of legal interpretation; by ruling the Negro outside of these beneficent rules; by claiming everything for slavery; by denying everything for freedom; by assuming that the Constitution does not mean what it says, and that it says what it does not mean; [and] by disregarding the written Constitution. It is in this mean, contemptible, and underhanded method that the American Constitution is pressed into the service of slavery.

Although the 1619 Project may contribute to our understanding of slavery and the African-American experience, its major premise that our founding ideals were insincere, and that slavery was the foundation and motivation for our regime, ignores antislavery voices of the Founding era in works like The Columbian Orator that Douglass affirmed so eloquently in his biographies.

As fate would have it, a young Abraham Lincoln was reading the Columbian Orator around the same time as Frederick Douglass. The two would famously meet on three different occasions during the Civil War. For both, that treasured book would express the principles they carried with them throughout their lives. Although Lincoln and Douglass differed over how best to achieve black freedom, they shared a common antislavery vision of the American idea that was clearly reflected in Bingham’s now forgotten book. This vision of universal human rights based on our common humanity was the common ground shared by these two antislavery giants in American history, and it is the common ground now renounced by the 1619 Project.