Bioethics

I Asked Thousands of Biologists When Life Begins. The Answer Wasn't Popular

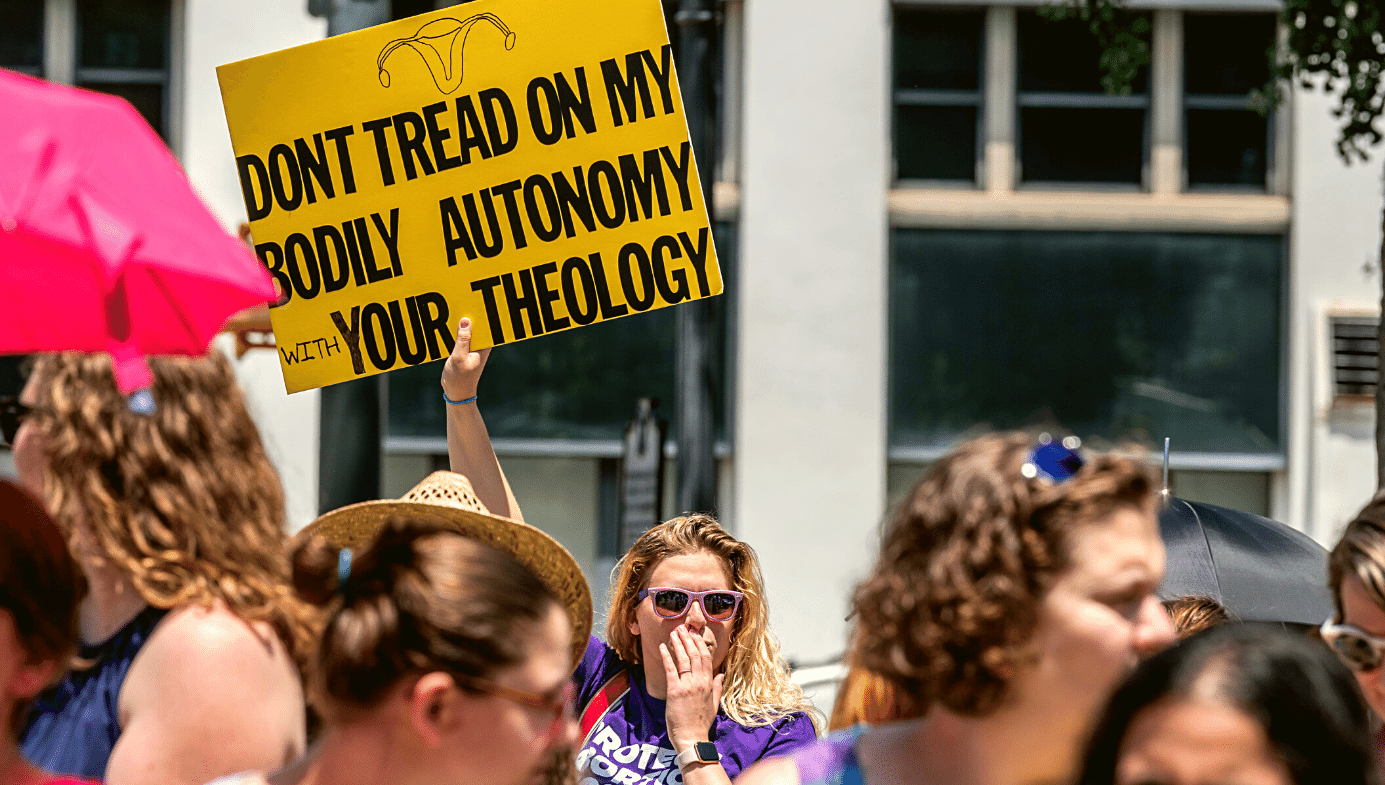

The U.S. abortion debate has raged for generations, and remains divisive to this day.

Shortly after being awarded my Ph.D. by the University of Chicago’s department of Comparative Human Development this year, I found myself in a minor media whirlwind. I was interviewed by The Daily Wire, The College Fix, and Breitbart. I appeared on national television and on a widely syndicated radio program. All of this interest had been prompted by a working paper associated with my dissertation, which was entitled Balancing Abortion Rights and Fetal Rights: A Mixed Methods Mediation of the U.S. Abortion Debate.

As discussed in more detail below, I reported that both a majority of pro-choice Americans (53%) and a majority of pro-life Americans (54%) would support a comprehensive policy compromise that provides entitlements to pregnant women, improves the adoption process for parents, permits abortion in extreme circumstances, and restricts elective abortion after the first trimester. However, members of the media were mostly interested in my finding that 96% of the 5,577 biologists who responded to me affirmed the view that a human life begins at fertilization.

It was the reporting of this view—that human zygotes, embryos, and fetuses are biological humans—that created such a strong backlash. It was not unexpected, as the finding provides fodder for conservative opponents of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court had suggested there was no consensus on “the difficult question of when life begins” and that “the judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, [was] not in a position to speculate as to the answer.”

The U.S. abortion debate has raged for generations, and remains divisive to this day. As a lawyer, mediator and researcher, I sought to assess whether there is room for compromise. I believed that such an approach could help Americans on both sides develop a shared understanding of the main issues—particularly surrounding the question of when life begins. My approach was similar to that implemented by Yale Professor Dan Kahan in his 2003 gun-control debate manifesto, in which he declared his objective as “not to take any particular position on gun control but instead to take issue with the terms in which the gun control debate is cast.” I was being idealistic, yes, but this approach was not without precedent.

“This dissertation seeks to explain why the abortion debate persists and whether it can be resolved,” I wrote in my dissertation’s introduction. “While the U.S. Supreme Court was able to end the national segregation controversy with its holding in Brown v. Board [of Education], the Court has twice failed to end the national abortion controversy [in the landmark Supreme Court cases of Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992]. The controversy has been resilient for decades, and it grows as some states pass laws to ban abortions throughout pregnancy, and other states legalize abortion throughout pregnancy. [T]his dissertation aims to understand whether the national controversy surrounding abortion is trivial or insurmountable.”

I employed a theoretical approach that was recently codified by graduates from my department: “[A] proposal to have a synthetic approach to social psychological research, in which qualitative methods are augmentative to quantitative ones, qualitative methods can be generative of new experimental hypotheses, and qualitative methods can capture experiences that evade experimental reductionism.” In practice, this meant going back and forth between qualitative and quantitative methods, leading in-person mediations with small groups, reviewing literature, and conducting surveys of Americans and the experts whose opinions they respected. My research timeline was roughly as follows, with each step being guided by what I already had learned from the previous steps:

- I led discussions between pro-choice and pro-life law students. Little progress was made because both sides were caught up with the factual question of when life begins.

- I surveyed thousands of Americans using Amazon’s MTurk service. I found that most Americans believe that the question of “when life begins” is an important aspect of the U.S. abortion debate (82%); that most believe Americans deserve to know when a human’s life begins in order to give informed consent to abortion procedures (76%); and that most Americans believe a human’s life is worthy of legal protection once it begins (93%). Respondents also were asked: “Which group is most qualified to answer the question, ‘When does a human’s life begin?’” They were presented with several options—biologists, philosophers, religious leaders, Supreme Court Justices and voters. Eighty percent selected biologists, and the majority explained that they chose biologists because they view them as objective experts in the study of life.

- I consulted with biologists, including a female University of Chicago Ph.D. genetics student; a female University of Chicago Ph.D. graduate; and a male professor—the biology expert in my department, who later served on my dissertation committee.

- I reviewed aggregated lists of biologists’ views in this area, studied the opinions of experts who testified before a 1981 Senate Committee on a Human Life Amendment, and the 2005 South Dakota Abortion Task Force. I also reviewed polls of Americans’ views on the question of when life begins.

- Since these sources suggested the most common view was that a human’s life begins at fertilization, I designed a survey to understand biologists’ assessment of that view. I emailed surveys to professors in the biology departments of over 1,000 institutions around the world.

- As the usable responses began to come in, I found that 5,337 biologists (96%) affirmed that a human’s life begins at fertilization, with 240 (4%) rejecting that view. The majority of the sample identified as liberal (89%), pro-choice (85%) and non-religious (63%). In the case of Americans who expressed party preference, the majority identified as Democrats (92%).

These data were not as surprising as some might imagine. Philosophers such as Peter Singer and Judith Jarvis Thomson have outlined abortion defenses that recognize a fetus’ humanity, while also rejecting the argument that fetuses have rights, or arguing that a pregnant person’s right to abort supersedes a fetus’ right to life. Unfortunately, that did not stop some academics from being angered by the very idea of being asked about the ontogenetic starting point of a human’s life. Some of the e-mails I received included notes such as:

- “Is this a studied fund by Trump and ku klux klan?”

- “Sure hope YOU aren’t a f^%$#ing christian!!”

- “This is some stupid right to life thing…YUCK I believe in RIGHT TO CHOICE!!!!!!!”

- “The actual purpose of this ‘survey’ became very clear. I will do my best to disseminate this info to make sure that none of my naïve colleagues fall into this trap.”

- “Sorry this looks like its more a religious survey to be used to misinterpret by radicals to advertise about the beginning of life and not a survey about what faculty know about biology. Your advisor can contact me.”

- “I did respond to and fill in the survey, but am concerned about the tenor of the questions. It seemed like a thinly-disguised effort to make biologists take a stand on issues that could be used to advocate for or against abortion.”

- “The relevant biological issues are obvious and have nothing to do with when life begins. That is a nonsense position created by the antiabortion fanatics. You have accepted the premise of a fanatic group of lunatics. The relevant issues are the health cost carrying an embryo to term can impose on a woman’s body, the cost they impose on having future children, and the cost that raising a child imposes on a woman’s financial status.”

Given those responses, one might suspect that I had asked loaded questions such as: “Since the human life cycle begins at conception, isn’t abortion tantamount to murder?” But I didn’t. I asked an open-ended question to ensure that respondents were able to fully express their views on when life begins. Moreover, I asked respondents to assess the following elements of the view that “a human’s life begins at fertilization”:

- “The end product of mammalian fertilization is a fertilized egg (‘zygote’), a new mammalian organism in the first stage of its species’ life cycle with its species’ genome.”

- “The development of a mammal begins with fertilization, a process by which the spermatozoon from the male and the oocyte from the female unite to give rise to a new organism, the zygote.”

- “A mammal’s life begins at fertilization, the process during which a male gamete unites with a female gamete to form a single cell called a zygote.”

- “In developmental biology, fertilization marks the beginning of a human’s life, since that process produces an organism with a human genome that has begun to develop in the first stage of the human life cycle.”

- “From a biological perspective, a zygote that has a human genome is a human because it is a human organism developing in the earliest stage of the human life cycle.”

After assessing the above statements and answering an essay question, the respondent biologists were then told that the survey “relates to the controversial public debate surrounding abortion.” It was at this point in the procedure that I received hostile responses, some of which are excerpted above.

In my dissertation, I proposed three possible motivations for these hostile reactions:

- Motivated Reasoning: Respondents experience cognitive dissonance when they recognize that their view of a fetus as a human complicates their political convictions in regard to abortion policy.

- Cultural Cognition: Respondents fear that public recognition of the scientific views they are expressing could lead to other people supporting abortion restrictions.

- Identity-Protective Cognition: Respondents fear that expressing their views may serve to estrange them from pro-choice liberals, on whom they might rely for social, emotional, or financial support.

I understand the subject of my research might have political ramifications. But, as neuroscientist Maureen Condic has noted, “establishing by clear scientific evidence the moment at which a human life begins is not the end of the abortion debate. On the contrary, that is the point from which the debate begins.” Yet the reception to my research suggests that many are going to ignore my findings out of fear of political repercussions.

I have concluded that one of the biggest reasons the abortion debate can’t be bridged is mistrust. I think this is primarily due to the stakes being so high for both sides. One side sees abortion rights as critical to gender equality, while the other sees abortion as an epic human rights tragedy—as over a billion humans have died in abortions since the year 2000.

Despite the one-sided stance of the majority of 2020 presidential candidates, my research indicates that Americans on both sides agree that the nation’s abortion laws should both ensure some abortion access while also providing some protections for humans in the womb. Indeed, I found that a majority of both pro-choice and pro-life Americans supported a compromise that restricted access after the first trimester of pregnancy, as described at the outset of this essay. This combination of policies is quite similar to the law of the land in many of the most socially liberal countries of Europe, which tend to balance abortion rights with fetal rights.

In my research, I was not advocating for such a compromise. However, advancing my own preferred outcome was not the point of my academic project. My goal was to use my training to establish common ground, learn whether a compromise was possible, and report on the most likely form such a compromise might take. An important takeaway is that both sides do agree on the arbiters of the question of when life begins.

While the justices in Roe could not answer the difficult question of when life begins, the U.S. Supreme Court might well revisit this question in the future. The Court can trust the uncensored viewpoints of biologists and acknowledge that scientific experts affirm the view that a human’s life begins at fertilization—even if some would prefer that this fact be hidden from view.