Free Speech

Theoterrorism versus Freedom of Speech—A Review

Not only had Carrell hurt the feelings of the Iranian people, but he had hurt the feelings of Muslims all over the world. There would be consequences.

A review of Theoterrorism versus Freedom of Speech: From Incident to Precedent by Paul Cliteur, Amsterdam University Press, 250 pages (February, 2019)

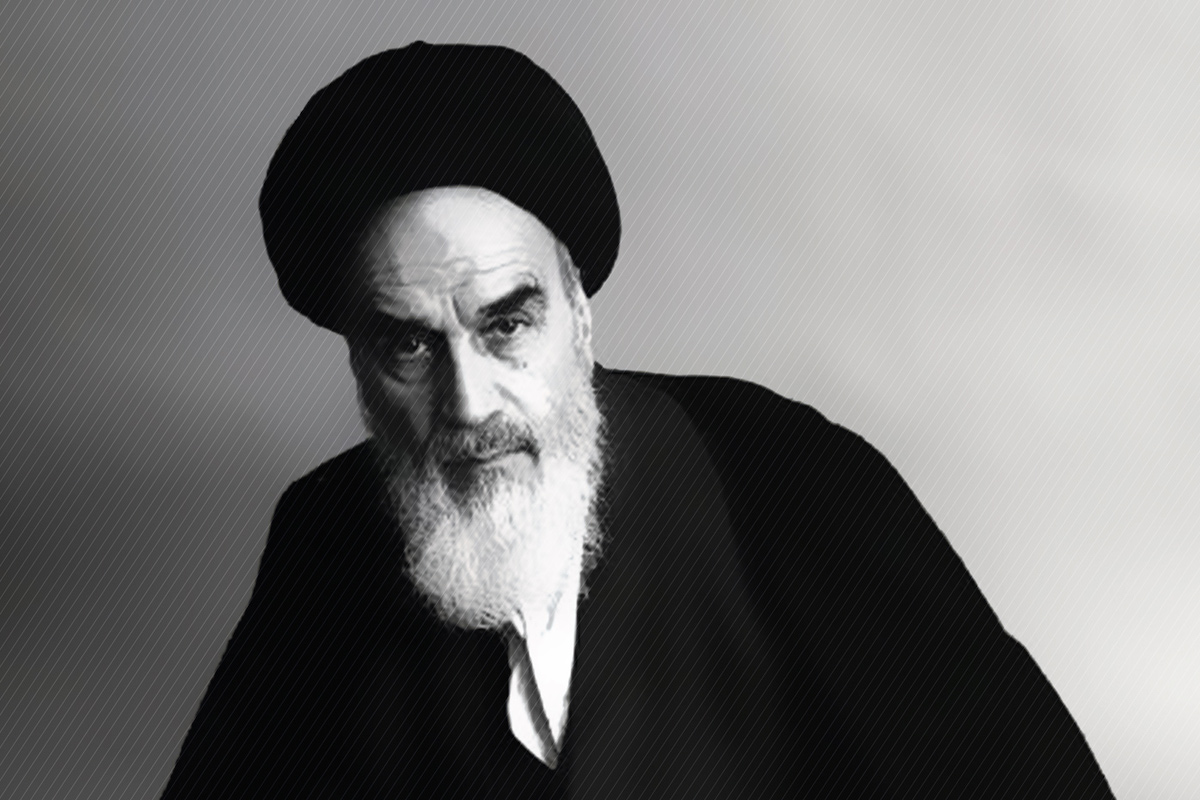

You will probably not have heard of the “Rudi Carrell Affair.” Paul Cliteur writes that this episode is largely unknown to the English-speaking world, and yet it changed history and marked the beginning of something new—the “theoterrorist suppression of free speech.” Carrell was a Dutch-born entertainer who hosted popular shows in Germany from the 1960s to the 1980s that reached 20 million people. Rudi’s Tagesshow (1981–87) lampooned famous personalities and politicians, including Willy Brandt, Nancy Reagan, Pope John Paul II, Helmut Kohl, and Margaret Thatcher. The episode transmitted on Sunday, February 15, 1987, included a short sketch in which women were shown throwing their underwear at Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini:

While lampooning international figures—including the pope—was acceptable under the umbrella of freedom of expression, Carrell was about to discover that the same rules did not apply to a major figure of Islam. As Cliteur states:

It is my claim that with this specific television fragment the strained relationship between contemporary theoterrorism and free speech becomes prominent. With that silly little fragment (only fourteen seconds long) starts a whole new era in international politics. The “Rudi Carrell Affair” is at the root of much better known controversies, most notably the Rushdie Affair, and from that moment onwards incidents will start to make a pattern.

In time, the pattern of events that followed Carrell’s show would indeed become familiar. The Iranian ambassador to Germany contacted the German civil servant responsible for the Middle East, and angrily informed him that the “highest supervisor of all Muslims” had been insulted. Not only had Carrell hurt the feelings of the Iranian people, but he had hurt the feelings of Muslims all over the world. There would be consequences, he promised.

These duly followed as Iran closed its consulates in West Berlin and Hamburg, two German diplomats were expelled, and the German ambassador to Iran was given a dressing down by the Foreign Ministry. Students protested outside the West German embassy in Tehran and demanded an official apology from Bonn over Carrell’s spoof. Carrell’s life was threatened and he received police protection. The German Foreign Ministry expressed regret that Carrell’s show had made fun of Khomeini but stressed the government’s commitment to artistic freedom. The following week, the Dutch Foreign Minister put pressure on a Dutch broadcaster not to show the segment. Carrell quickly succumbed to this onslaught and issued a profuse apology: “If my gag about Ayatollah Khomeini has created anger in Iran, I regret it very much and wish to be pardoned by the Iranian people.”

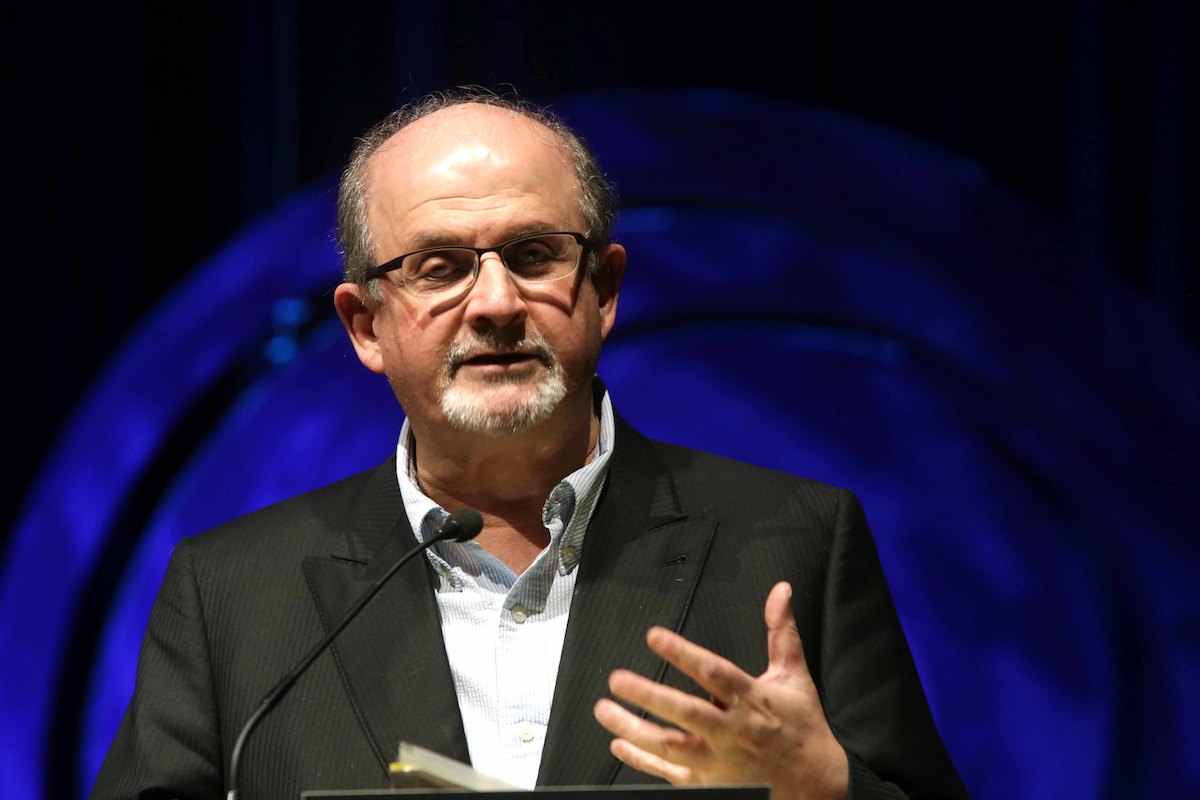

I presume that all readers of this article will have heard of the “Rushdie Affair,” which began with the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988, and exploded globally with Khomeini’s fatwa on Valentine’s Day the following year. The actions of Khomeini and the Iranian regime in both cases were acts of theoterrorism, Cliteur argues, explicitly designed to suppress freedom of expression. Cliteur provides extensive analysis of these episodes and their implications, before exploring further theoterrorist attacks on expression, including the slaying of the filmmaker Theo Van Gogh in 2004, the “Danish Cartoons Affair” of 2005, and the murderous attack on the staff of Charlie Hebdo in 2015. And he spends considerable space examining the arguments of those in the West who have defended the suppression of blasphemous speech on the grounds that great offence may be taken by religious believers.

The philosopher Charles Taylor, an important theorist and proponent of multiculturalism, attacked The Satanic Verses by arguing that:

In the West, we have developed explorations of the meaning of life, of the ultimate questions, which involve rejecting religion … the problem with this literature, as it has developed in a relatively self-satisfied Western world, is that it has lost touch altogether with the possibility religious symbols, stories, dogmas, might mean something very different to those who espouse them than they do to the rejecters.

Such reasoning dominated much of mainstream thinking back then, especially among liberals and the wider Left, and resulted in a dismal failure to show principled solidarity with Rushdie. Taylor took this to an unusual extreme with his ludicrous comparison of The Satanic Verses and the Iranian fatwa, one of which is a novel and the other a death sentence.

To my mind, the philosopher and devout Roman Catholic Michael Dummett came out of the debate about religious sensitivities and free expression looking even worse. Dummett’s position was not only illiberal, it was nasty and vindictive and unbecoming of an eminent logician. On February 11, 1990, while Rushdie was still in hiding under police protection and in fear of his life, Dummett published a tirade against him in the Independent entitled “Open Letter to Rushdie,” in which he pointed to the “untold damage” caused by the Rushdie Affair, although not to Rushdie himself. Instead, Dummett accused the beleaguered author of causing the “intensified alienation of Muslims here and in other Western countries from the society around them” who experienced “a far more severe imprisonment” than Rushdie.

Rushdie, he went on, “can never again credibly assume the stance of denouncer of white prejudice … now you are one of us. You have become an honorary white: merely an honorary white intellectual, it is true, but an honorary white all the same.” He continued: “If you really did not grasp the offence you would give to believing Muslims, you were not qualified to write upon the subject you chose.” To this, Cliteur provides the simple rebuke that the history of philosophy is full of “offensive ideas,” and notes that Dummett later supported extending the blasphemy law to cover other religions, arguing that “if there had been such a law, the Rushdie Affair would not have occurred.”

Preposterous, unprincipled arguments came from various other eminent persons. Roald Dahl dismissed Rushdie’s plight on the grounds that “he must have been totally aware of the deep and violent feelings his book would stir up among devout Muslims.” The art critic John Berger called on Rushdie to withdraw his novel, “not because of the threat to his own life, but because of the threat to the lives of those who are innocent of either writing or reading the book.” Cliteur highlights Berger’s dangerous suggestion that simply reading a book to which the theoterrorists object is enough to ensure guilt. John Le Carré pontificated that Rushdie should have withdrawn his book “until a calmer time has come”—most likely never.

Tony Benn, a leading figure on the Left of Britain’s Labour Party from the 1970s to the 1990s, also favoured the suppression of artistic freedom when confronted with theoterrorists. Benn opposed the publication of the Danish cartoons in 2005 on the grounds that “people’s faith should be respected … [the cartoons] have caused a great offence at a very sensitive time … You just do not insult people.” And a good deal of the UK press and media went along with this reasoning by refusing to republish the cartoons and criticising the Danish newspaper that had. Even Yale University Press became a party to censorship when it refused to allow the illustrations to be included in a book about the controversy by Jytte Klausen entitled The Cartoons that Shook the World. As Cliteur notes, “although the violent terrorists are most in need of criticism, it is precisely that category that benefits from multiculturalist non-judgmentalism.”

Cliteur notes that the assault on Charlie Hebdo a decade later ignited a worldwide discussion about the meaning and importance of free speech, and whether this principle is adequately protected in Europe’s diverse democracies. Some 43 heads of state (many of whom had little regard for freedom of expression) attended a four million-strong march in Paris in defence of this principle following the massacre. In the present context, the thinking of the new British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, is poignant. At the time of the assault in January 2015, Johnson was Mayor of London and described the Mayor of Rotterdam, Ahmed Aboutaleb, as his “hero” because the latter threw caution to the wind by telling the Islamists “if you don’t like freedom, for heaven’s sake, pack your bags and **** off.”

Furthermore, Johnson pointed out that hardly any paper in Britain had followed the lead of Charlie Hebdo and reprinted the offending Muhammed cartoons, correctly commenting that “you would have thought it was essential to the story.” Yet, after rejecting some of the most frequently repeated arguments for censorship, he confessed that as editor of the Spectator in 2005, he had also decided not to publish the Danish cartoons. He was remarkably truthful about this apparent hypocrisy by confessing that he had been afraid.

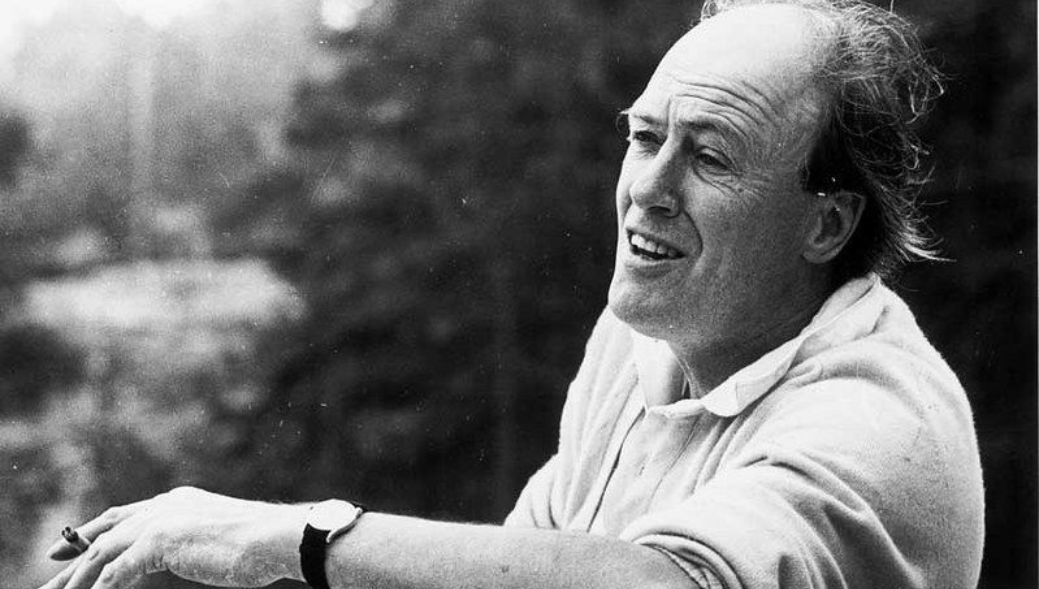

The day after the Iranian fatwa suborning the murder of Rushdie, the author Anthony Burgess took a principled, exceptional stance and showed great prescience by declaring:

The Ayatollah Khomeini is probably within his self-elected rights in calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie or anyone else for that matter, on his own holy ground. To order outraged sons of the prophet to kill him and the directors of Penguin Books on British soil is tantamount to a jihad. It is a declaration of war on citizens of a free country and as such, it is a political act. It has to be countered by an equally forthright, if less murderous, declaration of defiance.

Sadly, in the years since the Rudi Carrell Affair, it is appeasement rather than defiance that has characterised the position of most mainstream politicians, artists, and thinkers when confronted with violent threats. More than that, there has doubtless been much self-censorship when it comes to criticism or mockery of Islam, especially after the Charlie Hebdo murders in 2015—and, as Boris Johnson candidly admitted, it is surely fear that has been the decisive factor in this timidity.

Cliteur concludes his book by asserting that liberal democracies have no idea what has happened to them—under the guidance of identity politics, they have been distracted by senseless discussions of respect, dialogue, civility, turning the other cheek, inclusiveness, and avoiding hurting the religious sensibilities of so-called vulnerable minorities. A lamentable consequence is that Islamists have been allowed to sap the fibre of liberal societies.