Activism

The Rise of ‘Drag Kids’—and the Death of Gay Culture

There was—and will always be—promiscuity, homosexuality, prostitution, fetish culture and adultery—because sex is human.

Last month, the CBC—Canada’s public television network—ran a lavishly publicized documentary about “four kid drag queens as they prepare to slay on Montreal stage.” This was marketed as child-friendly content. Indeed, the CBC promoted the documentary, titled Drag Kids, on its “CBC Kids News” channel as a fun look at children who “sashay their way into the spotlight.”

For me, as a gay man, watching the documentary was traumatic. The interviewed parents defend themselves against accusations they are abusing their children by encouraging them to dress up in drag. But to do so, the parents must purport to separate drag from sex and sexuality, which is simply ahistorical. They define drag as “a way of expression,” and assure everyone that “there’s nothing sexual to it” (a premise that the CBC clearly embedded in the marketing around the documentary). The kids themselves are very much on message. One remarks, “I was called gay-boy, but I did nothing but dress up.”

That last remark actually brought tears to my eyes—though not for the reasons you might think. I cried not because of the homophobia directed against that little boy for dressing in drag. No, I cried instead because we now inhabit a culture that denies our real gay history of gender revolt—from the British “Molly Houses” of the 18th century (where homosexual men dressed up and held mock weddings and birthings), to the drag queens who threw the first rocks at Stonewall and invented gay liberation.

I thought a lot about that. And then I decided that as a gay man and drag queen, it was time to just, well, give up. After years of propaganda to the effect that sex is meaningless and “gender expression” is all that matters, it’s now official: Gay is gone.

* * *

As with many things gay, the trend started with AIDS. The disease did not, as was gleefully predicted by some homophobes, wipe out the fags. But it destroyed gay culture. In its place, we got Grindr, gay marriage, RuPaul on TV, prepubescent drag kids whose parents haven’t got a clue, and a preachy LGBT activist elite that prioritizes pronouns over the realness and rhapsody of human sexuality.

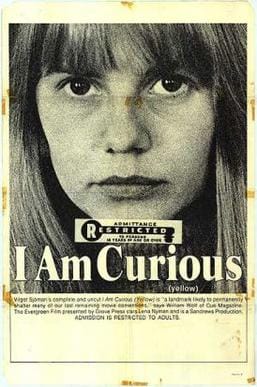

Gay liberation was born in the 60s amid the sexual revolution. Porn was going mainstream. Movies by gay filmmakers John Waters and Andy Warhol were seen in “legitimate” movie houses. In 1967, when I was still a child, Johnny Carson chatted about the Swedish art film I Am Curious Yellow, which featured hardcore sexual footage of a woman kissing a penis, on The Tonight Show. Later, I worked as an usher at Toronto adult cinemas called The Eden and The Eve. Back then, couples would go to porn movies on dates, dressed up fancy. The ladies would ask me, without irony, “Do you think I’d like this movie?” The unofficial spokespundit of the hippie movement, Herbert Marcuse, assured us that “obscenity is a moral concept in the verbal arsenal of the establishment, which abuses the term by applying it, not to expressions of its own morality but to those of another.” Wilhelm Reich told us, “the pleasure of living and the pleasure of the orgasm are identical. Extreme orgasm anxiety forms the basis of the general fear of life.” The pill came into wide use in the early 1960s, and Roe vs. Wade was decided a little more than a decade later. Sex no longer necessarily meant heterosexual procreation, and women were suddenly free agents. We, the sexual liberationists, thought nothing could stop the revolution.

Among the fundamental premises of gay liberation was that being gay meant being a sexual person. Chris Lea remembers that for the founders of The Body Politic—Canada’s first magazine devoted to gay liberation (founded in 1971)—sexual liberation was an obsession: “The Body Politic was very sexual. There was a kind of fundamental idea that sort of permeated. It was that promiscuity was the glue that kept the gay community together. They used to say that. It’s hard to believe, but they used to say that. So it made me into a kind of more sexual being for sure.”

Articles by gay men in that publication stretched the boundaries of what was considered acceptable sex. People discovered that sex outside marriage could produce joy, fun and even love through new, open, alternative relationships. Body Politic collective member Sue Golding (still a female, still a lesbian, but now known as Professor Johnny Golding) understood that “the body is political, and therefore that sexuality is political.” Golding later went on, in the 1980s—like many other sexually liberated lesbians—to defend On Our Backs, a magazine devoted to lesbian erotica. Women, people of colour, and the working class were oppressed, too, and we were all part of the same revolution.

Gender identity was also at the core of gay and lesbian liberation. But unlike now, the term was then understood as marking sub-typologies within a gay community defined by sex and sexual desire. In early gay pride parades, men proudly carried signs marked with slogans such as “pansy power,” and “dykes on bikes” (lesbians on motorcycles) led the march. There had always been “queens” and “trade” in gay culture (effeminate men and masculine ones); and lesbian culture was even more openly obsessed with the typology of “butches’ and “femmes.” Susan Sontag published Notes on Camp in 1964, linking gay humour with high art. Esther Newton published Mother Camp in 1972, a groundbreaking analysis of drag. One reviewer called it “a trenchant statement of the social force and arbitrary nature of gender roles.” Drag was beginning to be seen as a gay phenomenon that had implications for straight ideas and gender roles.

One of the most significant sexual events of the period was the 1977 opening of Studio 54 in New York City. For a while, respectable—even notable—straight people stood in line to attend what was essentially a gay bar. Men were screwing each other in the balcony while the likes of Paloma Picasso, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Betty Ford, Leonard Bernstein, Elizabeth Taylor and Salvador Dali partied down below. For a brief moment—it started with Playboy Club bunnies, and ended in a rumor-shrouded heterosexual sex club in Manhattan called Plato’s Retreat (1977-1985)—heterosexuals admitted they were sexual beings just like gay people. Not coincidentally, around the same time that straights and gays began mixing openly at Studio 54 and elsewhere, Anita Bryant initiated her anti-homosexual campaign. In 1979, Jerry Falwell founded the “Moral Majority,” opposing women’s rights, homosexuality and promiscuity more generally. AIDS delivered the tragic knockout blow that destroyed gay liberation and the sexual revolution. But much of the preparatory work already had been done.

In 1981, gay men in California started dying from what had been misidentified as treatable pneumonia. And gay men in New York City started dying from what was misidentified as cancer. In 1982, the Centers for Disease Control labelled this illness GRID, or “gay-related immune deficiency.” Later that year same year, they renamed it AIDS—“acquired immune deficiency syndrome.” In 1983, Jerry Falwell called AIDS—now being routinely referred to in some quarters simply as the “plague”—“god’s punishment against homosexuals.” In 1987, gay journalist Randy Shilts’ account of the AIDS epidemic, And the Band Played On, blamed the disease’s initial spread on a freewheeling Quebec flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas (1953-1984), thus hammering home the link between sexual promiscuity and AIDS. Watching what seemed like a medical holocaust of senseless deaths around them, gay men began to detach themselves from what had been a core belief—that gay and lesbian identity was intrinsically related to sexual liberation.

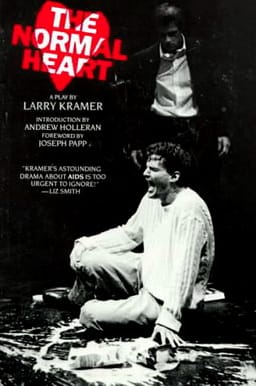

The sex itself was the first to go, at least in its public aspect. Gay men, in particular, felt the need to distance themselves from the world of gay bars and bath houses. Larry Kramer, whose 1985 play The Normal Heartdramatized the rise of AIDS, led the anti-sex faction. In his 1989 Reports from the Holocaust, he wrote: “I was against promiscuity long before The Normal Heart. I believe being gay offers much more than that.” Andrew Sullivan—a gay Catholic conservative who is still a prominent writer—wrote the book Virtually Normal (1995) in support of Kramer’s ideas. It was important for Sullivan to assert that we were “normal” and should have the right to marry, even if “marriage, of all institutions, is to liberationists a form of imprisonment.”

As part of their new quest to convince straights (and each other) that they were “normal,” gay men and women also began to distance themselves from gender issues (as gender was then discussed and expressed). There had always been some measure of discomfort about drag queens and butch dykes in the gay and lesbian communities. In the late 1980s, gay men started to dress like one of the characters in the 70s camp band The Village People—but without the humor—donning work boots and moustaches with a grim severity. A muscular physique became de rigueur—the opposite of the “pansy” epicene aesthetic I knew from when I was young. Gay men were now all about being “real men.” When I produced my play Drag Queens in Outer Space in 1986, drag-queen stars weren’t even allowed in many Toronto gay bars—until they began positioning themselves as fundraisers for AIDS victims, at which point they were grudgingly accepted. I remember sitting beside someone in a bar watching the drag icon Divine in a John Waters movie. Some gay drunk nudged me, saying “At least we’re finally through with all that.” And by “all that,” he meant (without knowing it) me.

The straight community was having its own reaction to the AIDS crisis, even if their per-capita death toll was much lower. AIDS functioned as much as metaphor as illness. For many, it symbolized the end of the sexual revolution. Kramer’s The Normal Heart, a hit among gays and straights alike when it opened 34 years ago, said it all: Gay men are normal. They’re just like everyone else. They don’t need promiscuity, but love. The AIDS doctor in the play wails, “Can’t you just stop having sex?” And the play ends with a gay marriage ceremony, inspiring viewers to go forth to the alleys, bathhouses and dark rooms with a message: “Turn back! Give up! Sexual excess will eat you alive.”

But of course, public denunciations of sex only push it underground. Though we are now living in a more conservative, uptight society, everyone is still hooking up on dating apps (or trying to, anyway). Of course AIDS is now rarely lethal; prescribed pharmaceutical drugs have made it a manageable chronic illness, and HIV-negative gay men take PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), which can guarantee 99% protection against AIDS. We also know that HIV positive men who have an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV.

Yet the 1960s and 70s still seem far away. The truth is that we don’t live in a sexual culture. We live in a prurient one, with the grubby aphrodisiac of digital porn creating a lonely underworld of sad loners who spend their days being preached to by a shrill chorus of puritanical scolds on both sides of the political spectrum. If anything, our hypocrisy is greater than it was in the 1950s, because it is now turbocharged by technology and social-media call-out culture.

There was—and will always be—promiscuity, homosexuality, prostitution, fetish culture and adultery—because sex is human. All that occurred during the 1960s and 1970s was that people began admitting openly what they were up to, with encouragement from the gay men who led by example. With AIDS came the defeat of sexuality’s gay shock troops, and a return to hypocrisy. For heterosexuals, this dipping in and out of the sexual revolution wasn’t particularly drastic, since they were simply able to return to their normal lives of respectable hypocrisy. But for gay men and women, the sexual counterrevolution was existential—because queer culture had defined itself in the brief dawn of the sexual revolution that the counterrevolution extinguished.

Indeed, gays and lesbians are, if anything, now arguably more hypocritical than straights—since many try extra-hard to appear more conjugally blissful, more church-going, more purse-lipped about what goes on in their bedrooms and brains. It has become politically correct to present modern gay men and lesbians as well-adjusted, loving, kind, asexual clean cut, family-oriented individuals (an archetype being Cameron and Mitchell on Modern Family). Supposedly, all gay men and lesbians are either happily married or aspire to be. Their sexuality is invisible and irrelevant.

So much so, in fact, that many don’t even feel the necessity to “come out” anymore—in large part thanks to the modern strain of trans ideology, which asserts that, among the civilized and enlightened, the primal physical needs associated with sexual orientation and body parts are trumped by the body-agnostic vagaries of self-declared gender identity. Indeed, how can there even be anything called gay (or lesbian) “culture” in a world that pretends to see no difference between a lesbian and a straight male-bodied man in a dress and pearl necklace?

And yet the stigma of being gay and lesbian hasn’t gone away. Homophobia is not dead in either the global or local sense. Big cities in North America are anomalous oases of tolerance. In some countries, it is still a crime to be queer. Even in North America, many parents are still shocked to discover they have a gay or lesbian child. I teach at the university level, and most of my gay students are not completely “out.” In some cases, I only find out about their identity after they graduate, which is when they tell me about the horrors of coming out to their parents. Drugs are a symptom of this: I remember my gay therapist telling me many years ago that most of his gay clients were so mired in self-hatred that they had to be drunk or stoned to have sex. The crystal-meth problem among gay men is a particularly acute problem.

It was about 2005 when my queer friends began to gossip about what we called ‘the disappearing lesbian.” It seemed that all of a sudden there were hardly any butch dykes, but a whole lot more “trans men.” My older butch lesbian friends complained about it, asking, “Doesn’t anybody want to be a butch lesbian anymore? Are they all taking hormones and cutting their breasts off?”

While young gay men tend to be addicted to sex and drugs, lesbians are more likely to get their fix on social media. Many will endure an adolescence struggling with gender issues, perhaps cutting themselves, threatening suicide, before coming around to the thoroughly fashionable notion that they’re definitely not lesbians, and so their problems have nothing to do with sexuality, and everything to do with “gender.” As Deborah Soh has pointed out, many of the adolescents who declare a trans identity will find out later that they are just gay men or lesbian women, though by that point much time will be wasted, and their truly transformative years will be gone.

This is how we arrived at the point where a documentary such as Drag Kids could be shown on—and indeed celebrated by—the CBC. As a lifelong drag queen, I know that it is silly to pretend that drag has no sexual connotation. But as someone who has been observing the slow death of gay culture for many years, I also know that this is not a new phenomenon, but rather just the end point in a cultural process that has turned the reality of gay men and women into an abstraction promoted by a gender-studies workshop.

Children should be encouraged to dress up and play as they wish, of course. But the parents who appear in the documentary want to have their cake and eat it, too: They want to allow their male children to act effeminately, but without acknowledging the connection to gayness—since gayness cannot stand in isolation from sexual orientation; which itself cannot stand in isolation from desire.

Drag is quintessentially gay and essentially sexual. It is a way for gay men to deal with the psychological effects of the homophobia that is directed against them by straight people. It always has been a way for gay men to exist in a homophobic society while proudly claiming their effeminacy, their love for other men, and, frankly, their proud status as “sex objects.” To create bubbly television fare marketed to Canadian children as wholesome (and even edifying) entertainment is at best ignorant, and at worst damaging.

The popularization of drag on RuPaul’s Drag Race has helped convince people that drag is not about sex, but about show biz. Even your grandma loves RuPaul. What you won’t see on Drag Race is the witty, chatty, virulently obscene monologues that still characterize real drag shows in the few remaining real gay bars that comprise the surviving vestiges of gay culture. And therein lies the tragedy of a world that ignores sex and fetishizes gender. A world that teaches kids it’s okay to be effeminate as long as you stay mum about being gay is a world in need of another sexual revolution.