recent

The Hell of Good Intentions—A Review

Walt is always thinking of ways to blame the most vexing international problems on liberal hegemony. From proliferation to terrorism to Trump, he sees its malignant influence everywhere he looks.

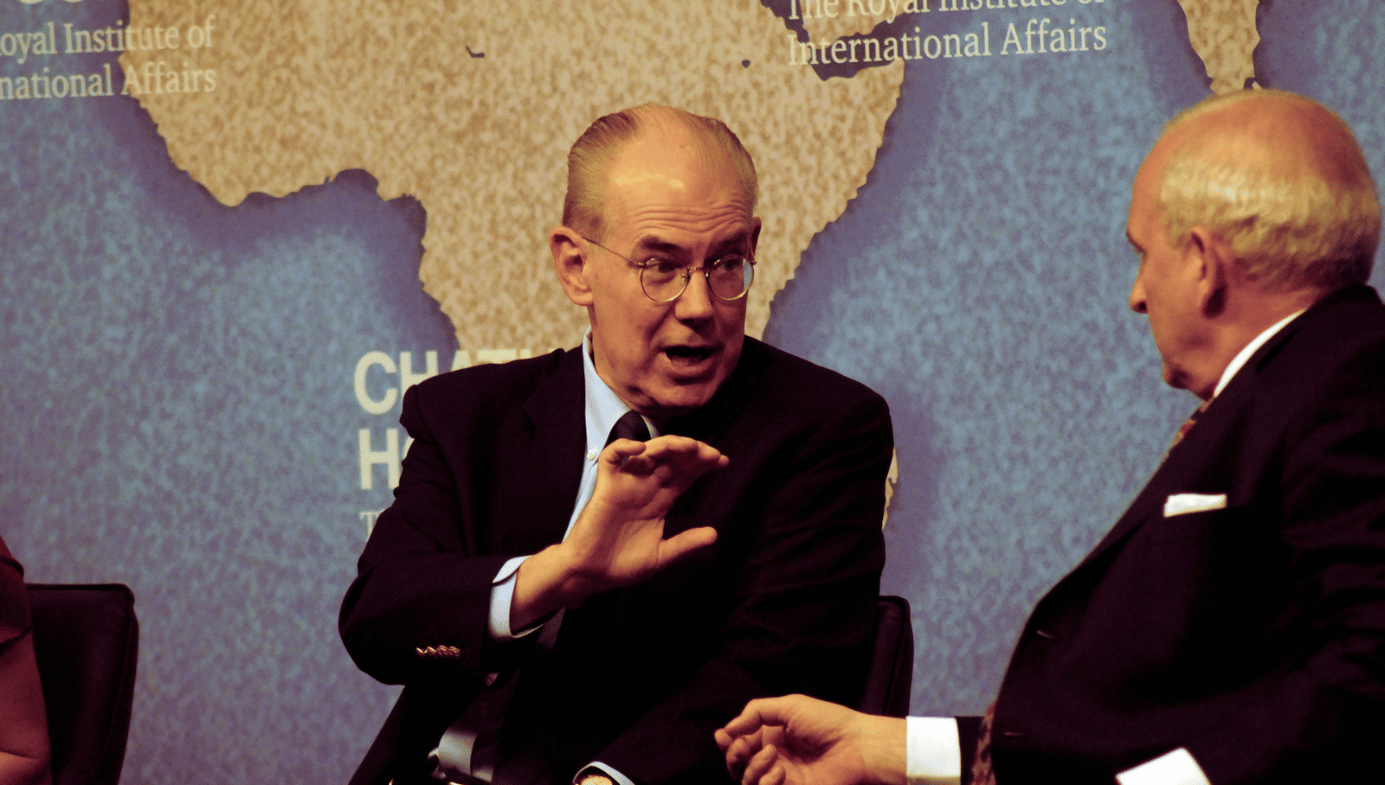

A review of The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy, by Stephen Walt. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, (October 2018) 400 pages.

Stephen Walt, a professor of international relations at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, is sick of academics, politicians, and journalists who regard the United States as the “indispensable nation,” which has to remain “engaged around the world” to ensure that the “US-led international order” is upheld.

These are the fundamental assumptions that have underpinned American foreign policy since the end of the Cold War—a foreign policy that goes by many names, depending on who you ask. Left-wing critics call it “neoliberalism” or “neoimperialism,” Hillary Clinton calls it “American leadership,” and Walt—author of The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of US Primacy—calls it “liberal hegemony.”

Walt isn’t alone in decrying liberal hegemony—John Mearsheimer (Walt’s collaborator and a fellow realist at the University of Chicago) published The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities around the same time as The Hell of Good Intentions, and The Quincy Institute was recently founded to advocate a more pragmatic and restrained approach to foreign policy in Washington. With the election of President Trump, who frequently derided American interventionism and the role of US-led international alliances and institutions during the 2016 campaign, critics of liberal hegemony saw an opportunity to challenge the “Blob”—the term President Obama’s Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes used to describe the foreign policy establishment in Washington, DC.

Walt and Mearsheimer are the best-known opponents of liberal hegemony from a “realist” perspective—a school of thought in international relations that emphasizes the role of states and the distribution of power over, say, the importance of promoting democracy and liberal values. Realists argue that, because the international system has no central authority, states are locked in a sort of Hobbesian trap of permanent competition, constantly vying for influence over one another. This is why Walt argues that the US should pursue a strategy of “offshore balancing,” which “focuses on preventing other states from projecting power in ways that might threaten the United States.” Accordingly, Walt says the US should “deploy its power abroad only when there are direct threats to vital US interests.”

On the other hand, Walt defines liberal hegemony as an ideology that “seeks to use American power to defend and spread the traditional liberal principles of individual freedom, democratic governance, and a market-based economy.” That’s the liberal part. The hegemony part is the idea that the US is “uniquely qualified to spread these political principles to other countries and to bring other states into a web of alliances and institutions designed and led by the United States.”

The Hell of Good Intentions is an attempt to explain the “dismal record” of post-Cold War US foreign policy. According to Walt, the main culprit is the foreign policy establishment in Washington, DC, which has remained stubbornly committed to liberal hegemony “even as the follies and fiascoes kept piling up.” While it’s easy to make a case against “follies and fiascoes” like the Iraq War, Walt is far more ambitious than that—he says the United States has failed in “nearly every key area of foreign policy” since the early 1990s.

Walt argues that the consequences of these failures are dire: The US is on worse terms with Russia and China than at any point since the end of the Cold War, rogue states have become even more dangerous, the US armed forces’ “reputation for competence and military superiority” and “America’s democratic brand” have been “tarnished,” liberal democracy is in decline and authoritarianism is on the rise, globalization created the conditions that led to the rise of Trump, Viktor Orbán, and other illiberal leaders, nuclear proliferation has continued, and terrorism has become more widespread.

Walt mentions “threat inflation” dozens of times in the book: “A time-honored method for selling an ambitious foreign policy,” he writes, “is to exaggerate foreign dangers.” But for Walt, threat inflation is also a means of convincing his readers that US foreign policy has been a disaster. Although he wants us to believe that a more restrained foreign policy makes sense at a time when the “dangers the United States faces are less daunting than in earlier eras,” he also has to demonstrate how dangerous the world has become as a result of liberal hegemony.

This is why Walt approvingly cites even the most hysterical threat inflators when they support his argument:

In 2014, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, judged the world to be “more dangerous than it has ever been.” In 2016, Richard Haass gloomily noted that “the question is not whether the world will continue to unravel, but how fast and how far.” Or as Henry Kissinger observed darkly, “The United States has not faced a more diverse and complex array of crises since the end of the Second World War.”

If these were quotations from a National Security Strategy or a report by the American Enterprise Institute, Walt would ridicule them as cynical excuses for the perpetuation of liberal hegemony. But as arguments against liberal hegemony, they suddenly become credible assessments of the state of the world.

Meanwhile, Walt ignores facts that are inconvenient to his thesis. For example, he explains that the “Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations all made democracy promotion a central goal of US foreign policy,” going on to observe that the United States’ “efforts to promote democracy and human rights have gone into reverse.” This analysis echoes recent reports by organizations like Freedom House, which have presented evidence of a “democratic recession” around the world. But if Walt is going to cite large-scale democratic trends, he should be honest enough to cite them for the entire period covered by his book.

Compared to the past three decades, the “democratic recession” is a statistical blip—in 1990, there were just 57 democracies in the world and 111 autocracies. In 2018, there were almost 100 democracies and only 80 autocracies. Far from being a period of “democracy demotion,” as Walt argues, the post-Cold War era has seen the largest democratic explosion in human history.

Walt is similarly selective in his appraisal of the United States’ efforts to promote economic liberalization. Before explaining why “globalization failed to deliver as promised,” Walt admits that “Lowering political barriers to global trade and investment did boost world trade” and “helped countries like China and India lift millions of people out of deep poverty.” Make that well over a billion people: In 1990, there were 1.9 billion people living in extreme poverty—36 percent of the planet. By 2015, that number had fallen to 733 million—less than 10 percent of the planet.

Of course, the United States doesn’t deserve credit for all of these developments. The world is a complicated place and it’s difficult to isolate the direct effects of US policy on the trends toward democratization and market liberalization. But it’s also difficult to determine the extent to which liberal hegemony has contributed to the problems Walt outlines, and in many cases, he just wants to blame US officials for as much as possible without demonstrating clear causal links between policies and outcomes.

A major theme of The Hell of Good Intentions is the idea that the United States squandered its “unipolar moment.” As Walt puts it: “When the Cold War ended, the United States found itself in a position of global primacy unseen since the Roman Empire.” Instead of taking advantage of this position, the US abused its power and overextended itself by expanding NATO and drastically increasing its other overseas commitments. A predictable consequence of these policies, Walt argues, is the return of great power politics: “Today, Russia and China are significantly stronger than they were, both are at odds with Washington, and Moscow and Beijing are collaborating more closely than at any time since the 1950s.”

This point reveals one of the biggest problems with Walt’s analysis: His selective use of evidence to argue that the most serious international problems the US faces can be blamed (for the most part) on liberal hegemony. For example, consider his claims about Russia: While eastward NATO expansion has undoubtedly antagonized Moscow, Walt repeatedly draws direct lines from US foreign policy to behavior it can only partially explain. While it would be idle to suggest that NATO expansion, the deployment of ballistic missile defenses in eastern Europe, and so on didn’t have an effect on Russian behavior, there are good reasons to believe Vladimir Putin’s revanchist impulses and the political conditions that already existed in Europe were more decisive causal factors.

In a discussion of US support for the pro-Western demonstrations against Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine, Walt writes, “Moscow responded by seizing Crimea and backing breakaway militias in eastern Ukraine, thereby halting Ukraine’s drift into the Western orbit.” Notice the inversion of responsibility here: The protesters took to the streets because Yanukovych refused to move forward on a political and economic agreement with the European Union. Despite the fact that Kiev had been drifting toward the EU for years and the Euromaidan movement was an organic reaction to Yanukovych’s stubborn allegiance to Moscow, Walt insists that Russia’s aggression was a response to the United States instead of the political realities in Ukraine.

In February 2014, the Ukrainian Parliament voted overwhelmingly to remove Yanukovych, and Russia invaded Crimea shortly afterward. In a March 2014 address, Putin argued: “In people’s hearts and minds, Crimea has always been an inseparable part of Russia.” Putin was losing his grip on Ukraine no matter what the US did, and his imperial attitude toward Crimea predated the crisis in 2014. While American support for the protesters certainly angered Moscow, it was far from the determinative factor that led to the seizure of Crimea.

Walt’s claims about liberal hegemony and the rise of China are even more dubious. While there are good reasons to believe Russian intransigence can be explained by a vast array of variables, one of them is certainly pressure from the United States. However, the evidence that a change in US foreign policy could have significantly impeded the reemergence of China as a great power is next to nonexistent—in fact, Walt demonstrates that liberal hegemony is one of the few significant checks on Chinese power.

It’s difficult to tell what point Walt is trying to make about China in The Hell of Good Intentions. He points out that China has become increasingly assertive, making bolder territorial claims in the South and East China Seas and increasing its economic influence in the region. But this would be happening regardless of what the United States did, and Walt gives us no reason to believe otherwise. He also makes strange connections without attempting to explain their significance, such as this one: “With the United States bogged down in the Middle East and elsewhere, in 2013 Beijing announced an ambitious ‘One Belt, One Road Initiative,’ a multibillion-dollar infrastructure project to develop transportation networks in Central Asia and the Indian Ocean.” Is he really suggesting that China would have held off on a massive, multi-regional economic initiative if the U.S. wasn’t “bogged down” in the Middle East?

If anything, Walt unintentionally makes a convincing argument that the biggest mistake the US has made with its China policy was the abandonment of liberal hegemony. It would be difficult to think of a more quintessential example of liberal hegemony than the Trans-Pacific Partnership—a major international trade agreement that encompassed 40 percent of global economic output and gave the United States a leading role in setting rules and regulations for the fastest-growing economies in East Asia. When the Trump administration withdrew from TPP, American economic influence in Asia was drastically reduced.

For someone as critical of liberal hegemony as Walt, his appraisal of Trump’s decision to pull out of TPP raises many questions:

Trump clearly saw China as a serious economic and military rival … and he understood that the United States needed to counter China’s rising power and growing ambitions. But if so, then abandoning TPP was an enormous misstep that undermined the US position with key Asian allies, gave Beijing inviting opportunities to expand its influence, and brought the United States nothing in return. It was also a mistake on purely economic grounds, as TPP’s remaining members went ahead with the agreement, depriving US exporters of more open access to a large and growing market and giving Washington no say over the health, regulatory, or labor standards embedded within the agreement.

Barack Obama couldn’t have said it better himself. Walt would doubtless argue that this was a case in which his realism happened to coincide with liberal hegemony, as checking China’s economic ambitions helps to maintain a balance of power in East Asia. But his arguments about TPP still undermine his core thesis. By Walt’s own admission, a vast US-led trade agreement was the most powerful check on China’s rising economic power. At the very least, this should lead us to conclude that liberal hegemony has its advantages.

Walt is always thinking of ways to blame the most vexing international problems on liberal hegemony. From proliferation to terrorism to Trump, he sees its malignant influence everywhere he looks. But although he makes persuasive arguments against the United States’ prosecution of the War on Terror and open-ended military engagements like Iraq and Afghanistan, he drastically overstates the negative influence of liberal hegemony and ignores its successes in other areas.

For example, after mentioning a few anti-proliferation victories since the end of the Cold War (such as the successful efforts to persuade former Soviet states to give up their nuclear weapons, the Nunn-Lugar Act, and the removal of Libya’s WMD stockpile), Walt argues that “US efforts to halt the spread of nuclear weapons achieved relatively little after 1993.” Walt doesn’t mention the major arms control treaties negotiated with Russia in the 1990s and 2000s (START I and II, SORT, and New START). Nor does he mention the fact that there were more than 55,000 nuclear warheads in the world in 1990—a number that has collapsed to around 9,200.

Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan weren’t the only countries that agreed to hand over their nuclear stockpiles at the end of the Cold War—South Africa did so as well. Meanwhile, countries such as South Korea and Japan pledged not to build nuclear weapons, largely thanks to the security guarantees provided by the United States. The American-led security umbrella in East Asia is another area where Walt is all in favor of liberal hegemony—he points out that a substantially reduced US presence in South Korea would “undermine the US role in Asia and constitute a major victory for North Korea and its Chinese patron.”

Walt’s assessment of the United States’ record on nuclear proliferation disregards the most significant anti-proliferation victories of the past 30 years. What’s more, his criticism rests on unconvincing assumptions, such as the idea that other countries developed nuclear weapons because they were upset about American hypocrisy: “Washington kept demanding that other states refrain from developing WMD, at the same time making it clear that it intended to keep a vast nuclear arsenal of its own.” He continues: “If the mighty United States believed its security depended on having a powerful nuclear deterrent, then surely a few weaker and more vulnerable states might come to a similar conclusion.” Does Walt really think vulnerable states needed the United States to demonstrate the advantages of having a nuclear deterrent?

According to Walt, the “perceived threat from the United States is the main reason why North Korea, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Iran were interested in acquiring a nuclear deterrent.” He doesn’t mention that all of these countries have major regional rivals (South Korea, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Israel, etc.) that account for their pursuit of nuclear weapons—a peculiar omission for a realist. This isn’t to say the threat of American intervention wasn’t a factor, but where’s Walt’s evidence that it was the main factor for each of the states he mentioned?

The Hell of Good Intentions presents a simplistic and selective picture of the costs and benefits of liberal hegemony. Walt’s arguments against nation building and the worst excesses of the War on Terror (the use of torture, Abu Ghraib, warrantless surveillance, etc.) are compelling, but most of his critics have already been convinced by those arguments. Meanwhile, he fails to substantiate his more controversial claims about the relationship between liberal hegemony and the “democratic recession,” great power rivalry, nuclear proliferation, and a wide range of other problems.

Walt refuses to engage with the strongest arguments against his position. In a section of his last chapter titled “Counterarguments,” he presents a few hypothetical objections to his criticism of liberal hegemony that don’t address any of the points outlined above. For example: Didn’t Muammar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, and Recep Erdogan do a much worse job than US policymakers? But Walt doesn’t point to a single academic, politician, or journalist who has made this argument or anything resembling it.

Other “counterarguments” include the claim that US foreign policy has outperformed “other public policy sectors.” Walt explains that this “misses the point” because there are “no benchmarks or performance measures available to rank different government sectors, making precise comparisons among them largely meaningless.” Well, yes. But who has actually tried to defend liberal hegemony by comparing it to domestic policy? Walt also says some of his critics may point out that “U.S. foreign policy is no worse today than it was in the past,” which sounds more like a concession than an argument.

With Trump in the Oval Office, the growth of authoritarian populism in Europe, the inevitable tension with a rising China and an increasingly aggressive Russia, the persistent threat of terrorism, chaos in Syria, Libya, and Yemen, and a wide range of other international crises and challenges, it’s easy to forget the successes of the past 30 years. So easy, in fact, that Walt finds himself looking back fondly at Cold War US foreign policy—the days of a “laserlike” focus on “containing and eliminating the Soviet rival.” The record of Cold War American policymakers may not be perfect (Walt makes passing references to Vietnam), but it’s “better than the parade of missed opportunities and self-inflicted wounds recorded by the four post-Cold War presidents.”

Is it? Vietnam was far more destructive than the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and it’s a bloody counterpoint to Walt’s claim about the “laserlike” foreign policy of the era. The Cold War was a time of obsessive military build-ups (in 1986, the US had two and a half times more nuclear warheads than the entire planet does today); violent and subversive clandestine operations everywhere from Central and South America to Southeast Asia; policies that had little to no regard for human life (such as the United States’ support for Saddam Hussein as he waged a catastrophic war with Iran, a policy Walt endorses as a prime example of offshore balancing); and nuclear brinkmanship with the Soviet Union that could have turned the entire planet into a radioactive inferno. Considering the historical context, a “parade of missed opportunities” doesn’t sound so bad after all.

Just as supporters of liberal hegemony should be realistic about its costs, critics should be honest about its benefits. Perhaps it’s true that the re-emergence of great power competition, the recent democratic setbacks in the West, and all the other problems Walt lists in his book can be blamed on liberal hegemony, but you’ll have to look elsewhere for the evidence.