Must Reads

Tourist Journalism Versus the Working Class

A few days before the Fourth of July, British comic John Oliver used the pulpit of his US infotainment show, Last Week Tonight, to deliver a lengthy monologue about the depredations of Amazon.com. His specific complaint was that Amazon doesn’t treat its employees very well. According to Oliver, among the indignities that the company has heaped upon its workforce are two separate instances in which a canister of bear repellant leaked in an Amazon warehouse. Oliver and his journalistic team also found former Amazon employees willing to complain on camera about working conditions in the company’s warehouses and fulfillment centers: they can get very hot in the summer and very cold in the winter; getting to the bathrooms sometimes requires a long walk; pregnant women get no special bathroom accommodations.

Oliver’s researchers even uncovered an incident in which a worker had died on the job and her co-workers were told to carry on working in the presence of her corpse. Amazon disputes much of this, but I have no difficulty believing that incidents like these do occasionally occur. Amazon employs approximately 650,000 people worldwide. That number is higher than the populations of 50 of the world’s 233 countries. It’s entirely possible that at some point a citizen of Luxembourg (population 602,000) has been sprayed by bear repellant, or that workers somewhere in Iceland (360,000) have been required to work around a fallen co-worker. But neither of these things, if they happened, would be proof that working conditions in Luxembourg or Iceland are appalling.

As it happens, I work in an Amazon warehouse in West Sacramento, California. When I showed up at a friend’s annual Fourth of July barbecue, I found myself besieged by well-meaning, right-thinking, Trump-hating friends, all of whom were eager to tell me just what a monstrous company I work for. This was weird because most of them know that Amazon has been a lifesaver for me financially, and they have heard me say how much I enjoy the work and appreciate the money. But they are now convinced that I work in something like a sweatshop. Bemused by this outburst of hostility towards my employer, I was led inside by our host who sat me down in front of his family’s 60-inch plasma TV screen to watch Oliver’s tirade, which he had courteously DVR’d for my benefit.

I have to say I found Oliver’s takedown unpersuasive. It is possible that Oliver was aware his material was a little thin, which is why he padded the segment with scattershot complaints about Walmart and Verizon (the enemy did not seem to be Amazon in particular, but large corporations in general). Warehouse work, Oliver solemnly informed his audience, is strenuous, difficult, and doesn’t pay very well. To most Americans (and people in general, for that matter), this will not have been news. Warehouses serve as temporary holding centers for consumer goods. These goods have to be offloaded from vast pantechnicons and brought into the warehouse. Later they will be loaded onto smaller vehicles, usually delivery vans, and sent out again.

The people who do this loading and unloading spend their days lifting toasters, boxes of kitty litter, minifridges, and thousands of other items, and carrying them to their designated storage rack. It’s a physically demanding job. Warehouses, such as the one I work in, have huge cargo bays that are almost always open to receive the back ends of incoming tractor trailer rigs. When these bays are open it is virtually impossible to control the temperature inside the warehouse artificially. If it is hot outside, the warehouse is likely to be very warm. If it is cold outside, the warehouse is likely to be very cool. Just about every working person in the world is aware of these facts, but John Oliver treated it like a scandalous revelation.

The Amazon facilities Oliver criticized are large fulfillment centers. There is one of these located near the Sacramento airport. I don’t work there. I work in a facility known as a “sortation center” (a name that Oliver would no doubt mock, not without some justification). It is smaller than a fulfillment center but it is still a large warehouse and the people who work in it are required to do a lot of lifting and walking, like warehouse workers everywhere. We are also advised to dress warmly in the winter and to wear light clothing in the summer.

Just about every job in my sortation center could probably be done by a robot. In fact, it amazes me that Amazon hasn’t simply automated the entire facility. After all, robots don’t call in sick, don’t steal from their employers, don’t sue for workman’s compensation, and they never complain about long hours or the heat or the cold. But nor do robots buy consumer goods. If I had to guess, I’d say that Amazon continues to employ lots of human beings because, by putting money into the pockets of working-class people, the company creates more customers. Robots may not buy basketball shoes or hibachi grills, but people sure do.

Apart from employing a lot of staff, Amazon does a number of things progressives ought to like. For instance, it employs a very diverse group of people. On my shift, I work with African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, white people, gay people, deaf people, ex-convicts, and people whose ethnicities and even genders are a mystery to me. I was hired the same day as a young Vietnamese-American named Lenny and a young Mexican-American named Ramon. They are both in their twenties. I am in my sixties. But because we started on the same day and went through training together, we bonded and became work friends.

Although Ramon is an American citizen, his wife, Angela, is not, despite the fact that she has lived in America since she was three months old. He’s angry that President Trump has backed off from the DACA program President Obama put in place to help people like Angela find a path to citizenship. Listening to Ramon discuss his first-hand dealings with immigration authorities has brought the issue alive for me in ways that reading news reports cannot. Ramon’s mother Rita, a woman in her forties who speaks little English, also works with us at the warehouse. I speak no Spanish, but Rita and I are friends. We often work side-by-side.

According to some authorities, Sacramento is the second most racially diverse city in America after Oakland, California. I have seen this statistic cited many times in local publications and it always used to surprise me. Most Sacramentans tend to self-segregate. Even when blacks and whites and browns live in the same neighborhood, or even the same block, they tend to hang out with their own ethnic group. I’ve noticed this in my own life. Almost all of my closest friends are white like me. But Amazon doesn’t allow its employees to self-segregate. The company wants every employee trained on every job in the warehouse. It also wants every employee to be able to interact with a wide variety of other workers.

Every morning, before our shift begins, my fellow Amazonians and I gather at the front of the warehouse where all of our photos and names have been printed on rectangles that resemble refrigerator magnets. These magnetic photos are stuck to a large white board with a diagram that represents every station in the warehouse. One-by-one each person’s magnet is assigned a place on the map. Every day brings a new arrangement. One day I may be pulling packages off the conveyor belt between a young Hispanic woman and an older black male. The next day I may be helping to stow packages in an aisle alongside two Vietnamese women.

This is a good thing. Working and cooperating every day as part of a diverse workforce can help clear up misperceptions. On my second or third day on the job I was paired with a young African-American woman who had been with Amazon a few weeks longer than I had. While talking to Celine, I learned that she Ubered to and from work every day because she didn’t own a car. The cost of the short ride was about $7.50 each way. In other words, she lost an hour’s pay every day just covering her commuting costs. When I discovered that she lived in a low-income housing project less than a mile from my house, I offered to drive her to and from work every day. She accepted.

At first, I was a bit apprehensive about this, perhaps because I’ve seen too many episodes of The Wire. But through my connection to Celine, I learned that the project is in fact just another quiet and orderly place filled with ordinary members of the working poor. Most of the occupants have jobs, and children, and they pay taxes like everyone else. Celine is a single mother with two jobs. In addition to her Amazon gig, she also works at a container store in a shopping mall located ten miles from her house. She takes a bus to that job. In fact, most of the people I work with have other jobs. Ramon works at a jewelry store. A girl named Imani has two other part-time jobs. I work evenings at a local independent bookstore. But almost all of these second and third jobs pay less than Amazon’s minimum wage of $15 an hour.

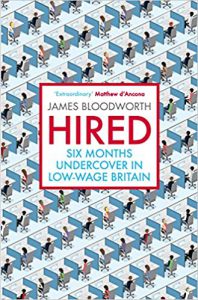

John Oliver is not the only British journalist to portray Amazon as the modern-day equivalent of an antebellum cotton plantation. In 2013, Carole Cadwalladr, a reporter for the Guardian, went undercover for a week at an Amazon fulfillment center in Swansea. Unbeknownst to her, while she was working there, Adam Littler, a reporter for the BBC’s investigative programme Panorama, was secretly filming his own exposé in the same warehouse. Then, in 2016, a British journalist named James Bloodworth went undercover in an Amazon fulfillment center in the small Staffordshire town of Rugeley. Bloodworth’s employment was part of the research for his book, Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low Wage Britain, an extract of which was subsequently reprinted in the London Times in February 2018 and subtitled “My Month Undercover in an Amazon Warehouse.” In September 2018, he wrote about the experience again for the Guardian (although here he says his stint only lasted three weeks). “This was a workplace environment,” Bloodworth warned the Guardian‘s readers, “in which decency, respect, and dignity were absent.”

And what did these intrepid reporters uncover? A whole lot of nothing, if you ask me. Both Bloodworth and Cadwalladr report that fulfillment center workers are required to do a lot of walking. Cadwalladr notes that all this walking caused one of her co-workers, a 60-something man she refers to as “Les,” to lose two stone (28 pounds) in two months. Bloodworth, on the other hand, claims he gained a stone (14 pounds) during his stint, despite walking up to 14 miles during a single shift according to a pedometer on his wrist (give me an hour or two in a rocking chair and I can put five miles on a pedometer; they are notoriously unreliable devices).

Cadwalladr reports that Amazon employees who call in sick three times in their first three months will be terminated. Bloodworth, who was employed three years after Cadwalladr, reports that six absences due to sickness will cost you your Amazon job in Rugeley. Things do seem to have been improving, then. Each offense is recorded as a “point” on an employee’s record. When I began working for them on March 23 this year, we were told that 13 points would prevent us from transitioning from seasonal employees to permanent ones. Even that figure is misleading. A lot of offenses (such as punching out in the middle of a shift without management approval) will cost an employee only half a point. Amazon recently sent me and my fellow seasonal employees an email informing us that, so long as we’ve been employed with the company for at least 30 days and accumulated no more than 12.5 points, we would be eligible for permanent positions. Theoretically, that means that an Amazon employee who joined the company 30 days ago and left work early without permission 25 times during that period, is nonetheless still eligible for a permanent position.

Some of what Cadwalladr and Bloodworth report seems rather histrionic. For instance, Bloodworth says that he had little time to eat a proper meal and quit buying bread and milk because these products always went stale/sour before he had a chance to use them. A fresh carton of milk is usually good for at least 10 days from the date of purchase. How many cartons of milk went stale during a three-week Amazon stint? And why not refrigerate or freeze your loaf to extend its life? His claim that he gained 14 pounds from junk food over a three week period during which he was walking an average of 10 miles a day doesn’t sound right, either. (It reminded me of “stunt journalist” Morgan Spurlock’s much-derided claim that eating every meal at McDonald’s for 30 days nearly wrecked his physical and emotional health.) Bloodworth even claims the Amazon job made him take up smoking again.

I don’t see why Amazon should be held responsible for its employees’ diets or personal habits, and a lot of this looks to me like buck-passing of personal responsibility. The fact that James Bloodworth was unfortunate enough to work with a racist Romanian woman doesn’t seem to me to be the fault of the company, either. With roughly 650,000 employees worldwide, it would be surprising if Amazon didn’t employ a cross-section of bigots and kooks.

Cadwalladr and Bloodworth make fun of the term “associate” which Amazon applies to its workers, and which both Cadwalladr and Bloodworth describe as “Orwellian.” While I prefer the term “worker,” I have a hard time working up much outrage over this. It certainly doesn’t strike me as particularly sinister or dystopian or totalitarian. Among the words the Merriam-Webster dictionary uses to define “associate” are: “worker,” “employee,” “business partner,” “colleague,” and “entry-level member of an organization.” All of those sound like reasonable terms to apply to a newly hired Amazon worker.

Bloodworth’s description of punishments dished out to Amazonians who break company policy as “draconian” is overwrought and his grievances are sometimes just unreasonable. He worked for Amazon for a total of three weeks but complains that his boss became upset when he took a sick day off. Maybe this is a generational thing, but my father always told me, “Never take a sick day during your first year of employment with any company, no matter what.” My wife and I have literally gone years between sick days. In the ’80s, I worked for a title insurance company that gave out a $500 bonus at the end of the year to any employee who hadn’t taken a sick day, and I earned that bonus five or six years in a row. If Bloodworth believes Amazon is inhumane for looking askance at a worker who asks for a sick day during his first three weeks on the job, then he and I live by different work ethics.

As for safety concerns, well, warehouses are hazardous environments and, somewhere today, an Amazon employee is likely to be injured. But I can attest to the fact that Amazon takes employee safety extremely seriously. Employees are briefed on safety before every single shift. We are required to wear high-visibility vests and protective gloves at all times. Traffic managers ensure that the vehicles continuously coming and going do not endanger employees. The conveyor belts are all equipped with emergency shut-off cords, which any employee can pull at any time should the need arise. Any Amazon employee who violates a safety regulation is likely to find himself without a job in a hurry. We have a fully stocked first-aid center. Our managers are obsessed with keeping us properly hydrated. Free bottled waters and electrolyte-enriched popsicles are located in ice chests all over the facility.

Bloodworth says he worked 10-and-a-half-hour days at Amazon, which sounds pretty brutal. Maybe they do things differently in the UK, but my Amazon sortation center is very flexible about the hours it offers. When I was applying for the job online, Amazon allowed me to create a schedule tailored to my needs. They asked me how many hours a week I’d like to work, and which days of the week suited me best. They asked if I preferred to work evenings, overnight, early mornings, days. After compiling this info, they gave me a shift that fits me like a glove. I work four and a half hours a day, five days a week. My shift begins at 6:30 am and ends at 11 am. But, when I need a bit more money, I can go to work at 5 am and pick up an extra 90 minutes of work pretty much whenever I want. Many of my co-workers add hours to their days whenever they are in need of a little extra cash, and we can take voluntary unpaid time off just about whenever we like.

James Bloodworth worked 35 hours a week. In America, at least, a full-time job consumes at least 40 hours a week. A 35-hour working week doesn’t sound especially harsh to me. And if he was working three 10-and-a-half-hour shifts per week at Amazon, then he worked just nine shifts during his time there (eight, if you subtract the sick day he took). I’ve worked about 70 shifts since I started at Amazon, and I still wouldn’t presume to offer myself as an expert on the conditions of the entire workforce. But I have seen enough to know that the picture painted by tourist journalists is highly misleading and unhelpful.

Amazon is not a perfect employer. I have a litany of gripes I’d be happy to share with you sometime. But I also have complaints about the small bookstore I work at in the evenings. I don’t know of anyone who doesn’t have complaints about their employer. Progressives tend to clamor about exposés that portray large multinational corporations like Walmart, Amazon, and McDonald’s as nothing more than cold-hearted exploiters of the working class. This type of thing does no one any good. If Amazon is going to be castigated publicly every time one of its 650,000 employees has a bad day, it may well decide to automate as many positions as possible and do away with most of its human workforce.

The problem with exposés like those mentioned here is that they don’t tell us how Amazon warehouses stack up against, say, warehouses operated by Home Depot (a former employer of mine), Starbucks, the New York Times, the Ford Motor Company, Microsoft, Barnes and Noble, or even Warner Media (the parent company of John Oliver’s television home HBO). We don’t know how many employee complaints a company with 650,000 workers can expect in a typical day or month or year. On July 1, the same day that Slate ran a largely uncritical story about Oliver’s anti-Amazon tirade, it published a highly critical story by Daniel Engber about the way (primarily right-wing) media outlets had reported on an alleged spike in American tourist deaths in the Dominican Republic.

When Engber actually took a look at the statistics for himself, he found that, not only is the Dominican Republic probably not experiencing a spike in American tourist deaths this year, it may actually be experiencing fewer tourist deaths in 2019 than in an average year. He recapped some of the more hysterical reports and then noted:

What a morbid waste of everybody’s time. Whether we’re talking about 12 deaths, or 25, or even 50, it’s wrong to treat the mere proliferation of these tragedies as proof that US tourists are in danger. If we want to know for sure that something is amiss—or even to make an educated guess about the same—we’ll need to have a baseline death rate for comparison. How often do Americans usually die while drinking whiskey in their rooms in Punta Cana? Or, to be less specific: How many US tourists die during a normal year of visits to the Dominican Republic?

Engber combed through governmental research as well as academic research. He asked questions, crunched numbers, and displayed an admirable skepticism for the dominant media narrative. In other words, he practiced responsible journalism.

Six years ago, I learned first-hand just how obstinate people can be when confronted with facts inconvenient to their preferred political narratives. I had just become one of the first beneficiaries of Obamacare by signing up for health coverage through Covered California. At family gatherings, my wife’s conservative family would say things like, “Not a single person has been able to sign up for health care through the state exchanges.” And: “The cost is so high that nobody who needs Obamacare can possibly afford it.” And: “Just wait until you try to access your coverage. You’ll have to pay hundreds of dollars just to see a nurse.” None of this was true, of course, but they refused to accept it. I started carrying around a copy of my monthly Covered California bill so I could prove to these people that Obamacare was working for at least some people. “That’s Covered California,” they’d say dismissively. “Nowhere on that bill does it say anything about Obamacare.” Try as I might, I couldn’t make them believe that Covered California was Obamacare and that it only cost me a dollar a month.

I faced the same stubborn refusal to acknowledge complicating information after John Oliver’s Amazon report, only this time it was my progressive acquaintances who were resistant. I assured everyone at the Fourth of July barbecue that the sortation center where I work is not a miserable sweatshop, that I am treated well, and that I am relatively well remunerated for work I enjoy. But they would not listen. They just looked at me sadly and shook their heads as if to say, “He’s drunk the corporate Kool-Aid.”

I don’t object to journalists writing about the trials and tribulations of Amazon employees. I only wish they would do so fairly. Just because a journalist has found an Amazon employee somewhere who got sprayed with bear repellant, that doesn’t mean Amazon employees spend their days in mortal fear of a chemical attack. In order for consumers to make informed purchasing choices, we need fair-minded and accurate reporting about the companies we patronize, not scaremongering polemics preaching a black-and-white gospel of tyranny and exploitation. Not all work done for a global commercial juggernaut like Amazon (or Walmart, or McDonald’s, or Starbucks) is, by definition, harsh, cruel, and damn near inhumane, fit only to be described ominously as “Orwellian” and “draconian.”

To university-educated media professionals like Carole Cadwalladr, James Bloodworth, and John Oliver, an Amazon warehouse must seem like the Black Hole of Calcutta. But I’ve done low-paying manual labor for most of my working life, and rarely have I appreciated a job as much as my role as an Amazon associate. Oliver insists that Amazon should be spared no criticism just because it raised its minimum wage to $15 an hour. That may not sound like much to him, but it’s huge for people like me. Among US states, California (along with Washington and Massachusetts) has the highest minimum wage at $11 an hour (for companies with more than 25 employees, it’s $12). The $15 an hour I earn from Amazon is nearly 40 percent higher than the $11 an hour I earn from the bookstore. In fact, thanks to Jeff Bezos’s generosity, I may soon be able to give up my second job altogether.

I am writing this on July 15—Amazon Prime Day, one of the busiest days of the year on the Amazon calendar. I put in a six-hour shift this morning at the West Sacramento warehouse. The workday wasn’t brutal. The company treated us all to a pancake breakfast in the break room during our 10-minute break. Of course, you can’t eat a pancake breakfast healthily in 10 minutes, but no one in charge complained about the fact that most of us spent at least 20 minutes eating. Yes, we were all encouraged to chant Prime Day slogans during our morning stretch. And we were all given little “Amazon Prime 2019” lapel pins and other bits of “flair” to wear on our high-visibility safety vests. So what? A bit of company spirit is downright American. I don’t mind being a small cog in the machinery of American commerce. It keeps the bills paid and my stomach from growling. But if John Oliver and his ilk keep harping away at how inhumanely Amazon treats its workers, Bezos might decide to completely automate his operation and people like me will be out of a job. And that will not only ruin my Fourth of July, it will ruin every other day of the year as well.

Quillette makes a small part of its revenue from Amazon sponsorship. Names (apart from the author’s) have all been changed.