Crime

Democrats Control America’s Most Dangerous Cities. So Why Do They Keep Passing the Buck on Gun Crime?

Progressives, who have long branded themselves as forward-looking policy innovators challenging the hidebound dogmas of conservatism, would benefit from challenging their own fixation on history’s rearview mirror.

Progressives and conservatives traditionally have exhibited different attitudes to the lessons of history. While conservatives have tended to take cues from the past as they build measured hopes for the future, progressives have urged that we break free from tradition in order to create bold and ambitious blueprints for a society they consider to be more just. In the United States, however, this pattern appears to be breaking down, as it is now progressives who tend to embrace a more rigid, backward-looking approach, especially on issues tied to identity. Unlike conservatives, progressives aren’t looking to revive a better, sometimes idealized version of their country. But they have become bogged down in the politics of historical redress, at the expense of forward-looking policies that would actually improve people’s lives.

A microcosm of this larger tendency was put on display during last month’s Democratic primary debates, which touched on the issue of urban gun violence. No Democratic presidential candidate expressed a sense of responsibility for the plague of violent crime in America’s cities, even though the largest urban areas are almost all controlled by Democratic politicians.

The issue first came up during questions posed to Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana. NBC’s moderators challenged Buttigieg by bringing up a recent incident in which a white police officer killed a 54-year-old black man. While that episode nominally relates to the issue of urban gun violence, it also allows Democrats to dwell in ideologically comfortable territory, since progressives have been drawing attention to police-involved shootings for years. (Indeed, it would be far more useful—and revealing—if it were instead conservative Republicans who were being pressed on this problem). Moreover, the preferred Democrat approach—tracing the problem to the country’s original sin of racism—isn’t especially helpful.

In answer to the question, Buttigieg dutifully offered a look back to history, noting “there’s a wall of mistrust put up one racist act at a time.” A question about the other shootings in South Bend—the vast majority of which are not committed by police officers—would have been far more illuminating. South Bend is one of the 30 most dangerous cities in America, with a per-capita homicide rate (16.8 per 100,000) comparable to that of Chicago (17.5 per 100,000). And this rate has remained virtually unchanged since Buttigieg became mayor in 2012, despite the seven years he’s had to address the problem.

At one point, the mayor did acknowledge the high death toll. “The worst part of the job is dealing with violence,” Buttigieg confessed. “We lose as many as were lost at Parkland [referring to the 2018 Parkland, Florida school shooting] every two or three years in my city alone. And this is tearing communities apart.” No doubt, this is absolutely true. But there is something oddly passive about the tone of such pronouncements, as if Buttigieg and other politicians were talking about a natural disaster. In truth, this ongoing tragedy is an indictment of American political leadership, including at the local level. If you can’t adequately fight crime as a mayor, why would one imagine you are fit to run a whole country?

Another presidential hopeful, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, showed a similar lack of self-awareness. Booker declared, in a tone that almost seemed to suggest pride, “I’m the only one on this panel here that had seven people shot in their neighborhood just last week. Someone I knew…was killed with an assault rifle at the top of my block last year.” Again, this sounds like someone reporting on a kind of naturally occurring cataclysm. Yet, in addition to serving as a senator from New Jersey for five years, Booker served as mayor of Newark for the previous eight. Newark’s government, like New Jersey’s, is part of the problem.

Like both men, I’ve seen the consequences of gun violence up close. The Toronto area, where I grew up, isn’t plagued by homicide rates comparable to those of large American cities. But we still lose dozens of young lives each year to guns. The level of fear I have felt upon getting a text about a shooting in front of my mother’s home, or hearing gunshots outside my own apartment, is only a fraction of that suffered by American families I’ve met in Newark, NJ, and Columbus, OH (a few hours southeast of South Bend). One thing I’ve learned through my work is that it’s hard for people of any age to move on from losing loved ones to violence. As author and journalist Alex Kotlowitz has explained, “[a] single act of violence—it shapes who people are. It gets in their bones.”

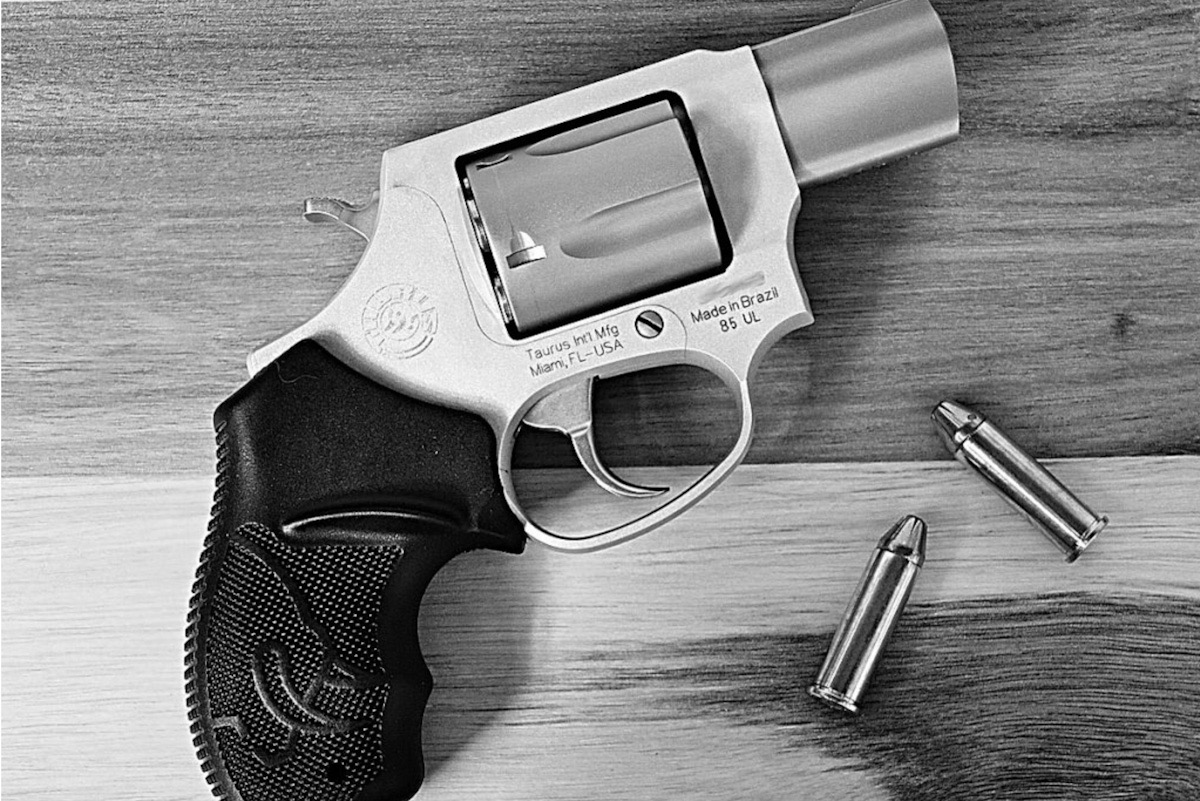

In keeping with their preference to remain on safe progressive turf, Democratic presidential candidates typically have limited their policy proposals in this area to gun-control measures—such as universal background checks (mentioned by Buttigieg during the primary debate) and a national buyback program (which is included in Booker’s platform). Yes, such top-down measures would be helpful, as most Americans agree, but they won’t fix the problem. A lot more can be done to make American cities safer, including local actions taken by Democrat-controlled city governments. And given the large number of Democratic presidential candidates, hailing from different parts of the country, this is an opportunity for a discussion of such policy ideas to take place on the national stage.

As mayor of Newark, for example, Booker himself saw double-digit reductions in shootings over the course of his first term (2006-2010). This is to his credit. And at the end of those four years, Booker credited a variety of city government initiatives for increasing community safety: more police officers, security cameras, gunshot-detection systems, services for ex-offenders, fatherhood support programs and an illegal-gun tip line. As mayor, Booker wasn’t waiting for either George W. Bush or Barack Obama to enact national gun-control measures. Booker took responsibility. Unfortunately, the positive changes didn’t last. After 2010, the Newark police budget was cut and targeted community programs started to lose funding. Newark’s homicide rate went back up to previous levels, further underscoring how local policies can make a meaningful difference. It would be nice to hear Booker talk more about this, rather than generic Democrat talking points.

The Democrats like to suggest that the problem of gun crime can’t ever be fully tackled until their party controls the White House and both houses of Congress, at which point they might pass aggressive gun-control legislation at the national level. But the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab has identified a meaningful role for city government initiatives in improving community safety. A 2014 empirical study of a summer-job program found that even part-time, minimum wage jobs can help reduce violent crime among youth in high-crime areas of Chicago by more than 40 percent. The study’s authors speculate that the program’s success is less attributable to poverty alleviation than to the social, psychological and cultural benefits of having a job. The City of Chicago has since implemented the findings by introducing summer job programs in local communities. And this might well be a factor in the decline in Chicago’s homicide rate since 2016.

More than 14,000 Americans died in firearm homicides in 2017, with most of the victims dying in cities. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, just over half of Americans consider gun violence, and violent crime more generally, to be “very big” problems. When you disaggregate the Pew survey responses by race, it’s clear that Democratic politicians have ample motivation to talk about these problems in a meaningful way. Among black respondents—a target group for any Democratic presidential candidate—82 percent identified gun violence as a “very big” problem. And twice as many black American respondents identified crime as a “major” problem in their local community, as compared to white Americans.

The small subset of killings that involve police officers is, of course, an important issue—especially since distrust of the police can make it harder for police to secure public co-operation in their investigations. Still, the Democrats’ disproportionate focus on this subset also seems influenced by political convenience. When white police are involved in the killing of a black man, it naturally invokes America’s horrific history of lynchings, Jim Crow segregation, slavery and other forms of state violence against black men and women—familiar territory for any Democrat on the hustings. Or, to use Buttigieg’s language, a significant part of progressive concern can be rooted in “what’s happened in the past.” The day-to-day violence within American cities, much of it involving young men as both victim and perpetrator, makes for a more awkward conversation—though it is a conversation that many black communities are willing to have.

The Democratic primary debates further spotlighted the party’s backward-looking disposition on race issues, through a particularly acute exchange in which Senator Kamala Harris attacked former Vice President Joe Biden’s decades-old opposition to federally-enforced school desegregation, or “busing.” But perhaps the best recent example of this larger trend within progressive circles emerged from last month’s U.S. congressional hearing on slavery reparations, which featured testimony from The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates and Quillette’s Coleman Hughes. As Hughes emphasized in a subsequent Quillette interview, there is literally “nothing” that can make up for the horror of slavery (not to mention convict leasing, vagrancy laws, debt peonage, redlining, racist GI bills and poll taxes). Those days are gone, as are its primary victims. And so it makes far more sense to work hard to address modern-day inequalities through improved public education, criminal justice reform and affordable healthcare. Unfortunately, this policy-oriented approach does not carry the same emotional (and political) resonance of a broad, dramatic call to remedy the ills of the past in one fell swoop.

Progressives, who have long branded themselves as forward-looking policy innovators challenging the hidebound dogmas of conservatism, would benefit from challenging their own fixation on history’s rearview mirror. A good start would come from engaging in an honest discussion of the daily criminal carnage playing out in the cities controlled by their own party. Preventing the deaths of today’s black youth would do a lot more good than dwelling on a racist past whose evils can never be undone.