Barbara Seaman

The End of an Era—A Feminist Firebrand Looks Back

As global violence against women gained horrendous momentum, many Western feminists became increasingly afraid to criticize that violence lest they be condemned as colonialists and racists.

After 9/11, I felt as if the Afghanistan I’d fled so long ago had followed me right into the future and into the West. That distant and dangerous country began to dominate American and European headlines. Muslim women started wearing burqas (head, face, and body coverings) and niqabs (face masks) on the streets of New York City, London, and Paris.

As global violence against women gained horrendous momentum, many Western feminists became increasingly afraid to criticize that violence lest they be condemned as colonialists and racists. This fear often trumped their concern for women’s human rights globally.

This was not the universalist feminism I helped pioneer. We favored multicultural diversity; we were not multicultural relativists. We called out misogyny when we saw it and didn’t exempt a rapist, a wife beater, or a pedophile because he was poor (his victims were also poor) or a man of color (his victims were often also people of color). We had little sympathy for a perpetrator because he had suffered an abused childhood (so had his victims).

Fighting for abortion and gay marriage rights in America is a legitimate undertaking, but so is standing with Muslim, ex-Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh dissidents, gays, and members of religiously persecuted minorities, all of whom are fighting for their lives.

World events have made feminist ideas far more important—yet, at the same time, Western feminism has lost some of its power. It’s now a diversionary feminism that is also far more invested in blaming the West for the world’s misery than in defending Western values, which have inspired countless liberation movements, including our own feminist revolution.

Celebrity endorsements of feminism or media-inspired Celebrity Moments, are not necessarily movements. If Helen Mirren, whom I love, wears a sparkly skirt in which the word “feminist” is embroidered again and again, I may like it, but I do not think it equivalent to the Emancipation Proclamation. The Balkanization of identity that passes for feminism in the 21st Century saddens me. Such Balkanization makes it almost impossible to unite in coalition to fight for issues that may not personally affect all the protestors.

Many feminist academics and journalists now believe that speaking out against head scarves, face veils, the burqa, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, and polygamy is somehow racist. I did not foresee the extent to which feminists who, philosophically, are universalists would paradoxically become isolationists. Such timidity (presumably in the service of opposing racism) is perhaps the greatest failing of the feminist establishment. Postmodern ways of thinking have also led feminists to believe that confronting narratives on social media or signing petitions are as important and world shattering as rescuing living beings from captivity.

I recant none of the visionary ideals of Second Wave abolitionist feminism. Rather, as a feminist—not an antifeminist—I feel obliged to say that something has gone terribly wrong among our thinking classes. The multicultural canon has not led to independent, tolerant, diverse, or objective ways of thinking. On the contrary; it has led to conformity, incivility, and totalitarian herd thinking.

Do I now regret founding women’s studies?

No, I do not. Expanding the canon to include women of ideas, women’s history, and radical and original feminist views was long overdue. My generation’s feminists forever empowered me. I’m in their debt. They share in my accomplishments.

However, as of the 21st Century, I find myself surrounded by an angry, entitled, and barbaric patriarchy. I am referring to the movements to ban or restrict abortion; legalize and/or decriminalize prostitution and to legalize commercial surrogacy; the quantum rise of sex slavery and trafficking as well as Islamist terrorism, gender apartheid, and censorship; the obsession with transgender victimization; the disappearance of “women” from women’s studies which long ago morphed into gender studies and then into LGBTQIA studies; and in the massive increase and normalization of pornography.

In addition, the 50th anniversary of Stonewall and gay celebrations remember those who died from AIDS but not those who died from ovarian, uterine, or breast cancer. Domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, and incest, are not mainstay subjects in what used to be Women’s Studies. Now, the hot button issues are diatribes about Western-only colonialism, queer people of color, police brutality against young black men, “Islamophobia,” etc. In short, radical feminism is losing on every front.

That the “good-old bad-old times” didn’t last, that illusions were shattered and people were betrayed is hardly unique. Perhaps, if the world keeps spinning on its axis, another great opening in history may come round, and if our best work is preserved, and preserved accurately, future generations may be able to stand on our shoulders.

May this memoir stand against the rank and swelling tide of revisionist feminist history.

By now, at least 100 active pioneer feminists I knew or with whom I worked or whose work brightened my days have died— and with them, an entire universe is gone.

I’m here—but without so many I’ve cherished.

Most women cannot survive without their female friends; we tend to have a handful of best friends, not just one. I could not have stayed the warrior’s course without such intimates.

Here are some of the souls with whom I served. We were soldiers, brave and true; we were friends, near and dear.

Barbara Seaman (1935–2008) was the author of The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill (1969), Free and Female (1972), and Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones (1977).

Barbara and the Boston Women’s Health Collective essentially founded the feminist health movement. Barbara lost her lucrative income as a magazine writer when the drug companies—whose ads fueled women’s publications—insisted that she be blackballed. And so she was—but she saved the lives of millions of women.

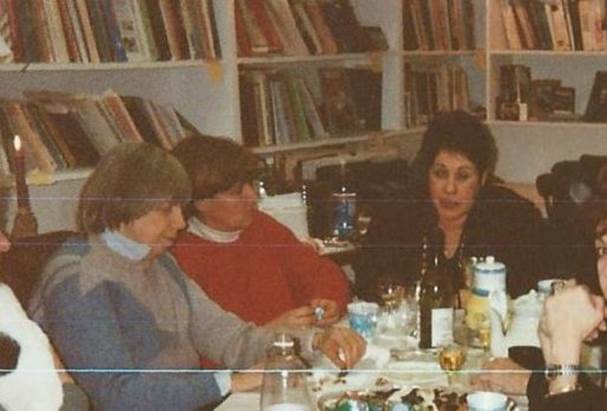

Barbara Seaman and Phyllis Chesler, 2002-2003. NYC.

Barbara cofounded the National Women’s Health Network—and the network was really her baby. It is still going strong. Barbara mentored newcomers and strategized and shaped the network’s agenda. She was generous with her time and resources. She turned no one away and would find just the right physician for any woman who asked, no matter where she lived. Always, always, when she had to change literary agents, she would insist that I move with her, so keen was she to share her contacts. I did so only once, but it was a good fit until that agent died.

Barbara was as generous to stars as she was to woebegone waifs. With a few exceptions, she thought the best of everyone.

Barbara remained connected to me even though we disagreed strongly on certain issues. When ideological or political splits of one kind or another swirled around us, we held each other close. I have no doubt that she took some heat on my account, but she never mentioned it if she did.

Barbara wore dresses and low-heeled shoes and sometimes a string of pearls. I suspect that she probably once wore hats and gloves. But she was one of us, perhaps a more gracious rebel than most.

Barbara never complained about her personal woes. She shared some heartbreaking secrets with me—but never belabored the point. She told only a few of us that she was dying of lung cancer and did so only toward the end. Although she was dying, she came to my son’s wedding. I have her happy, smiling face in a photo that I’ll forever treasure.

Jill Johnston (1929–2010) wrote many articles and a bevy of books: Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution, Gullible’s Travels, Mother Bound.

We knew each other before she became famous for her girl-on-girl kiss at Town Hall in Manhattan in 1971—a great piece of performance art, if you ask me—and an action that horrified both Norman Mailer and most of the assembled feminists.

Of course, I was there—we all were—to see Germaine Greer, Jacqueline Ceballos (then president of the New York City chapter of the National Organization for Women); Diana Trilling, the literary critic; and Johnston, the irrepressible lesbian journalist, take down the ever-pugnacious and attention-hungry Mailer, who had been spoiling for a fight with feminists.

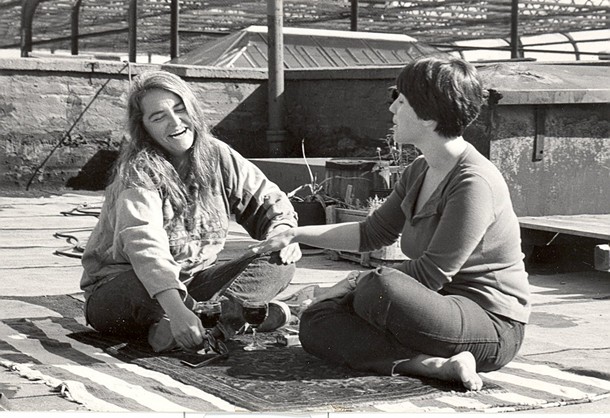

Jill Johnston, Ingrid Nyboe, Phyllis Chesler. Mid-1990s. NYC.

Mailer had written an antifeminist screed, ‘The Prisoner of Sex,’ for Harper’s Magazine, in which he had been grossly unfair to Kate Millett. Germaine wore a feather boa and flirted outrageously with him that night. Billed as a debate on the issues, it was, in turn, serious, ridiculous, upsetting, and funny. The women were in favor of women’s liberation. Mailer was just in favor of women, so long as they knew their place.

Jill was a bohemian, a butch girl, an artiste, a gadfly, an outcast, a word dancer. Her long public kiss at Town Hall was her out-of-the-box response to an otherwise serious evening. Jill did that a lot—tried to steal the show, mess things up.

Jill kept asking me why I thought she had to come out as a lesbian in her 1971 Village Voice column under the famous headline ‘Lois Lane Is a Lesbian.’ I had no answer for her.

I saw her through a long list of lady loves until she found Jane O’Wyatt and then Ingrid Nyeboe, both of whom grounded her most nobly. Jill loved being legitimately married; she and Ingrid tied the knot in Denmark, where gay marriage was legal. At the time, I thought that marriage had laid the ladies low—but because Jill was so obsessed with being legal (her parents had never married, and she never knew her British father), I understood that she was driven by psychological as well as practical motives.

Of course, we had our differences—many differences—but to her credit, our credit, we continued to wrestle with them. The subject of anti-Semitism was a live wire for us. However, Jill and I fought to remain connected to each other no matter what.

One time, in the early 1980s, we saw Gone With the Wind at a movie theater out in the country. We mourned the death of poor Gerald O’Hara, the loss of Tara, the doomed Melanie and Ashley, Bonnie Blue, and Scarlett, too. It was like an opera, really. We were two opera queens who happened to be female.

Jill reminds us of our youth, both aesthetically and politically; she is gone now and so is our youth—it is gone, gone with the wind.

She was an original. We will not see her like again.

I cannot believe she is dead—although it’s been years now—or that she—that changeling child, that Huck Finn, that quintessential Peter Pan—actually managed to turn 81-years old.

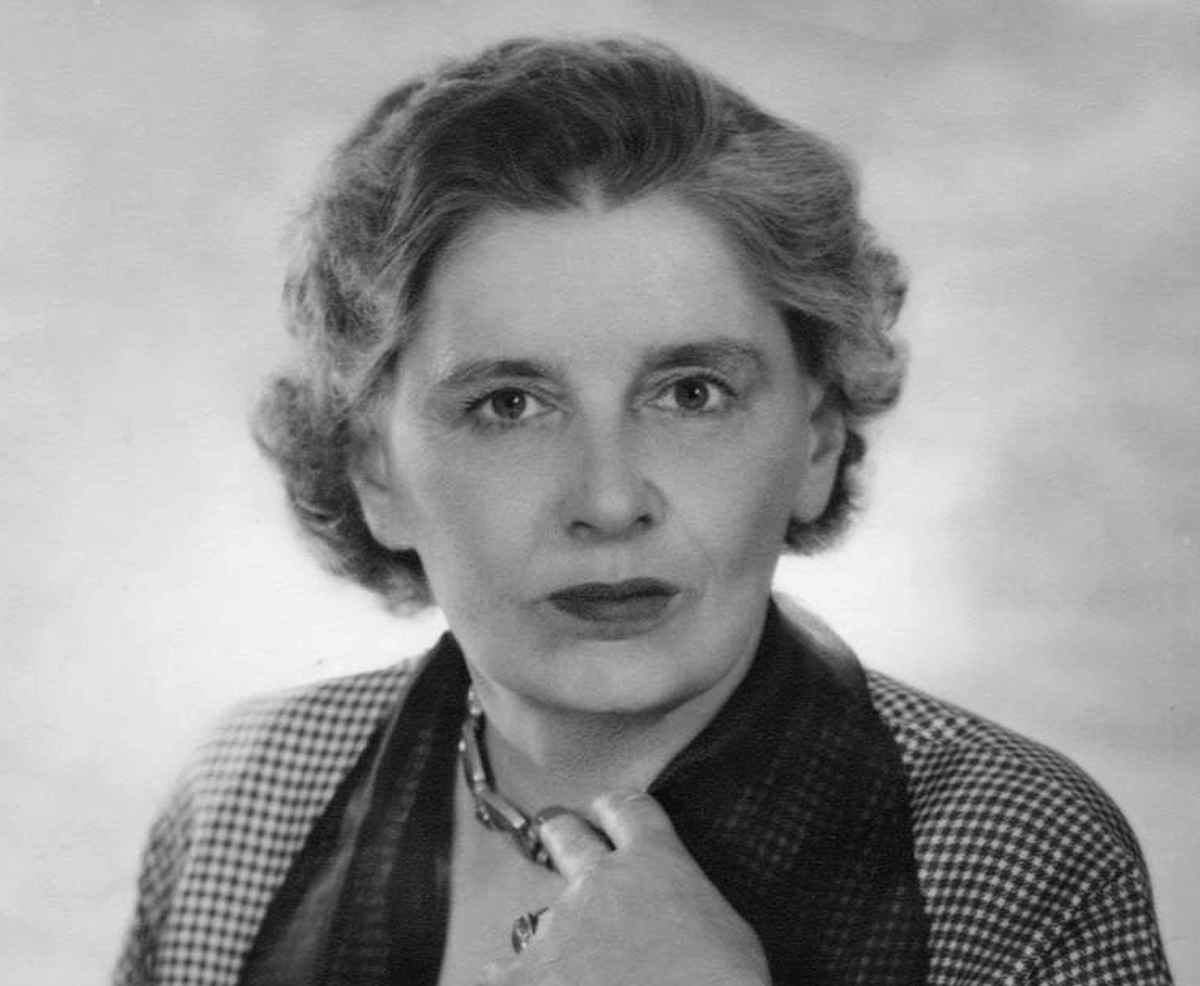

Kate Millett (1934–2017)

Kate: You took your last breath on Earth in the city you loved most: Paris, the city that once welcomed the expatriates Gertrude, Alice, Pablo, Ernest, and Sir James of Dublin, and where the early morning aroma of fresh bread was reason enough for you to rise, too.

I finally understood you in historical context when I read Andrea Weiss’s Paris Was a Woman: Portraits from the Left Bank. Then I recognized your culture, one in which sophisticated and talented lesbians took many lovers, competed with each other for sexual favors, slept with their lovers’ lovers, and everyone either became lifelong friends or abandoned each other or the group entirely.

Kate Millett and Phyllis Chesler. 1975-1976. NYC.

You were just another Irish rebel living in exile. Wherever you lived, you were in exile. When you were in Paris, you were not at home on the Bowery, and when you were in New York, you missed the farm. Just as you belonged to many cities, you also had many different selves. You were many different Kates.

You were Kate, the highly ceremonial hostess, offering your guests wine as if it were a libation to the gods; floating little candlelit paper boats out on the lake at the farm for the Japanese holiday of Obon every August. You were also Kate the raging Mad Queen; Kate the unbearably humble; Kate the increasingly all too silent.

You were also Kate the straight, a married lady, who genuinely loved your husband, Fumio. Do you remember how you wept when he finally left? You called and, between tears, said that he’d left you for another woman. I was amazed but I dared not laugh. Your grief was so raw. Finally, I asked you: “But Kate, really, how many women have you left Fumio for?” I could not reason with you, your sorrow and shame were genuine.

You were the most cosmopolitan, the most continental, the most European of our feminist intellectuals (well, Andrea Dworkin was, too). You believed that ideas matter and that intellectuals must lay their bodies down for the sake of revolution.

You were always broad-minded (in both senses of the word); you would not have disapproved of my exposing you here, given how routinely you exposed yourself and everyone else in book after book, and you did so in such a fine, stream-of-consciousness prose, one that was underestimated by critics but never by me. I admired it; no, I adored it. I was going to read you the passages about you—but then you went ahead and died. You’d been drifting for some time now, whether you were in another country, upstate at the farm, marooned in a hospital, or sitting right across the table from me; before you were really gone for good, you were no longer exactly “here.”

For years now, when we would meet at the Bowery Bar, right across the street from your loft, you were already far too quiet. Sophie (Kier), Susan (Bender), sometimes Merle (Hoffman) had to join me in keeping the patter going. But you still had your wonderful laugh and your wise and twinkling eyes which signaled that you understood everything.

From time to time, you’d call and leave the most heartbreaking messages: “Hi, this is your old friend Kate Millett, remember me?” And I’d call you right back. Sometimes we were able to have a real, if only a brief, conversation, but only as long as I carried the weight for both of us. You no longer raged—at least, not at me, not on our precious phone calls, never again in person either.

On one of your visits a few years ago you told me you were working on a book about your relationship to de Beauvoir, to the woman and her work, perhaps a book that might encompass your relationship with the entire French Literary Enterprise.

I understood that you were no longer capable of undertaking a Big New Book, but I quietly volunteered to listen to you talk about this, tape your every word, and help you edit this if you wished. You said yes—but we never spoke about it again. Eventually, I heard that you were working on introducing something that you’d written long ago, perhaps your Tokyo diary, maybe something else altogether.

Although you attended marches, protests, press conferences, and sit-ins, you mainly read, wrote books, sculpted, painted, and tried to create a utopian community for lesbian artists.

You were also the Kate who could easily pass for a homeless person, out on the Bowery trying to sell your farm-grown Christmas trees in blustery winter weather. (Oh, how chapped your hands were, how red were your cheeks.)

You were Kate the sharecropper, who, like Gerald and Scarlett O’Hara, was adamant that owning land is everything and that land must be kept in the family at all costs. You drove a tractor, cut wood, stood on dangerously high ladders to get at a failing roof.

Do you remember the time I visited one weekend when I was on a hard-and-fast deadline and you demanded that I just put my shoulder to the wheel of your sheltered workshop and help you repair the roof? (I sometimes viewed the farm as your personal alternative to a loony bin.) “C’mon, Chesler,” you growled, “just get on the goddamn ladder and help me do this.”

I was horrified. Terrified. Flabbergasted. But you would not let go of me until I at least planted a victory garden of flowers by your side.

But even as Kate the farmer, you still sometimes drank your morning coffee from a French ceramic bowl, always made little toasts at dinner, and were, at all times, surrounded by books and bookshelves. Your Sexual Politics was perhaps the most influential or at least the most famous of the Second Wave feminist books—although we all stood on the shoulders of those brilliant articles and demonstrations that preceded us. That same year Shulie published her equally amazing The Dialectic of Sex.

I loved Flying, in which you captured the energy of the early days of breakneck activism, as well as the unexpected cruelty of some feminists, but you also described fame as something of a human sacrifice. Ah, Katie: You were tireless, relentless, in trolling the dark side on behalf of women’s freedom, and you did so doggedly, even during the dark days, the dog days, the days of despair.

In The Basement: Meditations on a Human Sacrifice, you more than equaled Truman Capote and Norman Mailer in your fact-based but fictionalized account of the physical and sexual torture-murder of 16-year-old Sylvia Likens in Indianapolis at the hands of a middle-aged woman named Gertrude Baniszewski, her teenage daughter and son, and some neighborhood children. They tortured Sylvia most horribly for weeks and then carved “I’m a prostitute and proud of it” into Sylvia’s skin. The details are unbearable. How did you bear it? Did you?

I remember how shocked I was by your art installation on this subject. I did a double take when I realized that the Sylvia mannequin on the floor was dressed in your clothing and had a wig on that was styled exactly the way you styled your hair.

In Going to Iran, you truly grasped the misogynistic nature of an Islamic theocratic regime that would go on to murder its best and its brightest.

Do you remember our Christmas Eve parties and the presents we all exchanged? And the New Year’s Eve parties, too? I often had to initiate the process; each time you went along with it and were always eventually very pleased—but always, always, like Shulie, you also stood a bit apart, watching it all, too silent even among your cherished intimates.

Katie: I want to thank you for your generosity, for always trying to include me, and for suggesting that others do so, too. You introduced me to extraordinary women. As you know, some of these women became very dear to me.

It was a privilege to be your friend. I will never forget you.

Read our interview with Phyllis Chesler by Louise Perry.

Excerpted, with permission, from A Politically Incorrect Feminist: Creating a Movement with Bitches, Lunatics, Dykes, Prodigies, Warriors, and Wonder Women by Phyllis Chesler. ©2018. Published by St. Martin’s Press. All rights reserved.

Phyllis Chesler, Ph.D, is the author of 18 books, including Women and Madness, Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, and An American Bride in Kabul.