How Anti-Humanism Conquered the Left

There are some notable environmentalists who recognize the fact that humans are capable of creating abundance instead of scarcity.

Today is International Workers’ Day, a holiday with socialist origins. Its name hearkens back to a time when the political Left was ostensibly devoted to the cause of human welfare. These days, however, some on the far Left care less about the wellbeing of people than they do about making sure that people are never born at all. How did these radicals come to support a massive reduction in human population, if not humanity’s demise? Whether it’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez questioning the morality of childbearing, a birth-strike movement that encourages people to forego parenthood despite the “grief that [they say they] feel as a result,” or political commentator Bill Maher blithely claiming, “I can’t think of a better gift to our planet than pumping out fewer humans to destroy it,” a misanthropic philosophy known as “anti-natalism” is going increasingly mainstream.

The logical conclusion of this anti-humanist ideology is, depressingly, the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (Vhemt). According to its founder, activist Les Knight, Vhemt (pronounced “vehement”) is gaining steam. “In the last year,” Knight told the Daily Mail, “I’ve seen more and more articles about people choosing to remain child-free or to not add more to their existing family than ever. I’ve been collecting these stories and last year was just a groundswell of articles, and, in addition, there have been articles about human extinction.”

Over 2000 new people have “liked” the movement’s Facebook page since January and, more importantly, the number of people fulfilling the movement’s goals (regardless of any affiliation with the movement itself) is growing. The U.S. birth rate is at an all-time low. According to the latest figures from the Center for Disease Control, the total U.S. fertility rate for 2017 was at an all-time low of 1.77 babies per woman (i.e., below the replacement rate of 2.1 babies per woman needed to maintain the current population).

Recent examples of writings that are warming to the idea of human extinction include the New Yorker’s “The Case for Not Being Born,” NBC News’ “Science proves kids are bad for Earth. Morality suggests we stop having them,” and the New York Times’ “Would Human Extinction Be a Tragedy?” which muses that, “It may well be, then, that the extinction of humanity would make the world better off.” Last month, the progressive magazine FastCompany released a disturbing video entitled, “Why Having Kids Is the Worst Thing You Can Do for the Planet.”

Some anti-natalists are not content with promoting the voluntary reduction of birth rates, and would prefer to hurry the process along with government intervention. Various prominent environmentalists, from Johns Hopkins University bioethicist Travis Rieder to science popularizer and entertainer Bill Nye, support the introduction of special taxes or other state-imposed penalties for having “too many” children. In 2015, Bowdoin College’s Sarah Conly published a book advocating a “one-child” policy, like the one China abandoned following disastrous consequences including female infanticide and a destabilizing gender ratio of 120 boys per 100 girls, which left around 17 percent of China’s young men unable to find a Chinese wife. Even after that barbaric policy’s collapse, she maintains it was “a good thing.”

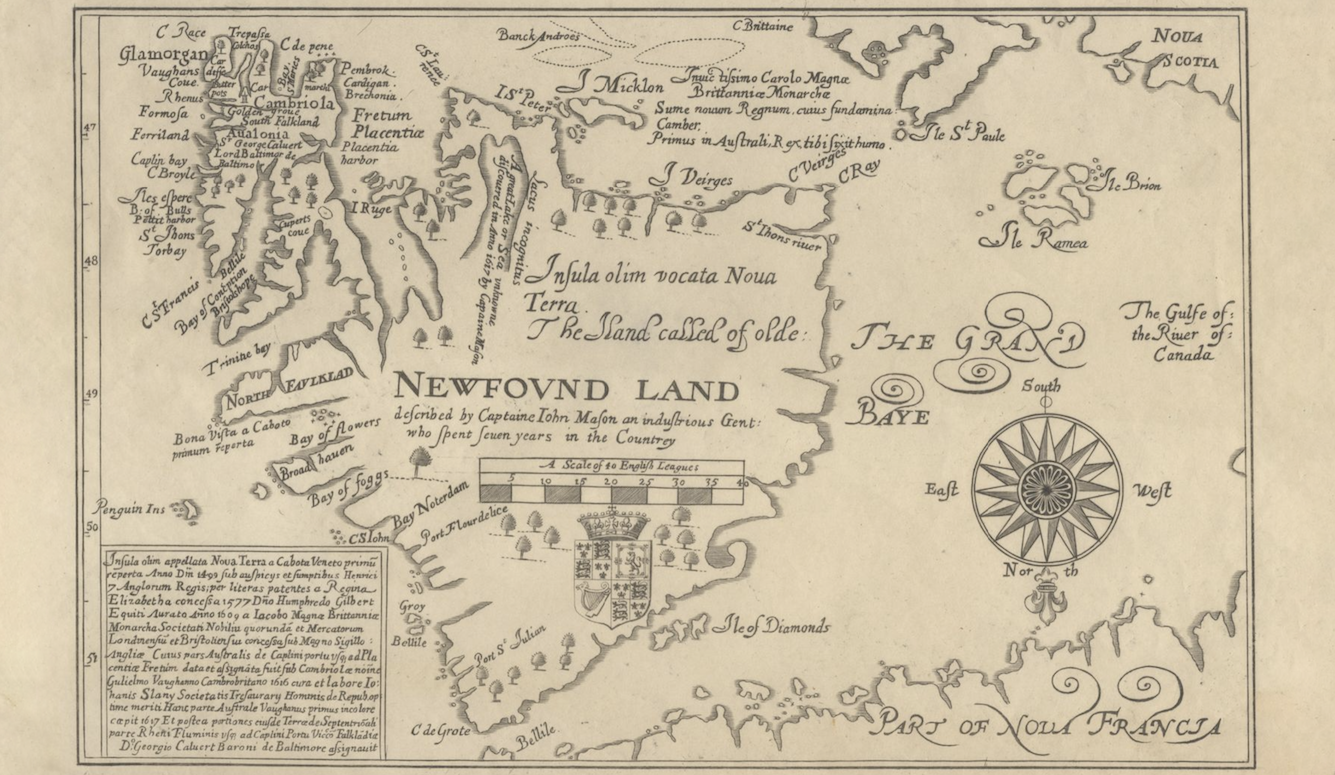

Modern-day anti-humanism emerged in the 1970s, midwifed by a doomy strain of environmental pessimism led by Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich (but with intellectual antecedents dating back to Thomas Malthus in the eighteenth century). Ehrlich published his widely read polemic The Population Bomb in 1968, which originally opened with the lines, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.”

Thanks to human ingenuity in the form of the Green Revolution, that didn’t happen. The challenge of feeding a growing population led instead to technological innovation and that produced a solution: higher agricultural productivity and falling food prices. Far from leading to starvation, more humans exchanging ideas and innovating have ensured that the supply of food rose to meet growing demand. Ehrlich quietly removed his failed prognostication from subsequent editions of his book, but his ideas caught on among some strands of the environmentalist movement.

Undeterred, Ehrlich and many likeminded doomsayers are still claiming that disaster is imminent, despite their previous predictions repeatedly failing to materialize. Just last year, Ehrlich compared human population growth to the spread of cancer, informing the Guardian, “It is a near certainty in the next few decades, and the risk is increasing continually as long as perpetual growth of the human enterprise remains the goal of economic and political systems … As I’ve said many times, ‘perpetual growth is the creed of the cancer cell.’”

Once anti-humanism had infected the environmental movement, it soon spread through the political Left. Robert Zubrin’s book Merchants of Despair gives an overview of the Left’s reversal of its traditional commitment to advancing the human condition, in favor of a project that viewed humanity as a plague upon the Earth:

Instead of The Grapes of Wrath, they carried copies of The Population Bomb … Instead of “Stop the War,” their buttons read “Stop at two” [children]; instead of “Power to the people,” their slogan was “People pollute.”

These environmentally-concerned anti-natalists believe that a world without humans, or with significantly fewer of them, would eventually revert to a pollution-free paradise with abundant natural resources. As one human extinction proponent put it just last month in a letter to his local paper, “In approximately 20,000 years after human extinction, this magnificent resistant biosphere will return to its perfection.” If humanity fails to reduce its numbers, extinction proponents fear resource shortages and environmental catastrophe. “How could anybody,” an official Vhemt member, Gwynn Mackellen, wondered aloud to the Guardian, “produce a new human when the effects of humans are very obvious, I feel, and the situation is getting worse.”

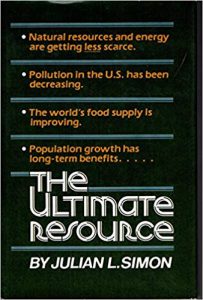

These extinction advocates, however, have misunderstood the evidence about population growth’s impact on the planet and its resources. The late University of Maryland economist Julian Simon rejected the idea of overpopulation as a problem. He believed that, on the contrary, more people in the world means more people to solve problems, and less resource scarcity. “There is no physical or economic reason,” he wrote, “why human resourcefulness and enterprise cannot forever continue to respond to impending shortages and existing problems with new expedients that, after an adjustment period, leave us better off than before the problem arose.”

In his 1981 book The Ultimate Resource, Simon argued that humans are intelligent beings, capable of innovating their way out of shortages through greater efficiency, increased supply, or development of substitutes. Humans, with their inventive potential, are themselves, in Simon’s phrase, “The Ultimate Resource.” A growing population produces more ideas. More ideas lead to more innovations and more innovations can improve productivity. That higher productivity then translates into more resources to go around and better standards of living.

In 1980, Simon made a bet with Ehrlich. Ehrlich would choose a “basket” of raw materials that he expected to become more scarce in the coming years. At the end of a specified time period, if the inflation-adjusted price of the basket was higher than at the beginning of the period, that would indicate the materials had indeed become scarcer and Ehrlich would win the wager; if the price was lower, that would mean the resources had instead become more abundant, and Simon would win. The stakes would be the ultimate price difference of the basket at the beginning and end of the time period. Simon ultimately won, and Ehrlich duly sent him a check for the price difference.

New research, inspired by the Ehrlich-Simon wager, has further confirmed that, contrary to the anti-humanists’ claims, population growth goes hand-in-hand with more abundant resources. Consider the amount of time it takes an average worker to earn enough to buy a basket of common commodities—the “time-price” of those items. The Simon Abundance Index found that between 1980 and 2017, “the time-price of our basket of 50 basic commodities declined by 0.934 percent for every one percent increase in population. That means that every additional human being born on our planet seems to be making resources proportionately more plentiful for the rest of us.”

There are some notable environmentalists who recognize the fact that humans are capable of creating abundance instead of scarcity. Environmentalists who take the rational and techno-optimistic view, sometimes called “enlightenment environmentalists” or “ecomodernists,” still believe in humanity’s ability to tackle environmental problems with innovation and ingenuity. Examples include Harvard University’s Steven Pinker and the Breakthrough Institute’s Michael Shellenberger, who both hold that technologies such as nuclear power can reduce emissions. And the research of Rockefeller University environmental science professor Jesse H. Ausubel, who was integral to setting up the world’s first climate change conference in Geneva in 1979, has shown how technological progress can allow nature to rebound, even while food and other resources have become more plentiful.

Unfortunately, ecomodernists are still a minority within the environmental movement. Too many people, mostly on the political Left, still agree with Ehrlich that humans are analogous to cancer cells and long for the reduction or even extinction of our species. One third of Americans in the millennial generation say they are deeply concerned about the environmental impact of having children. Not that long ago, well within the living memory of a millennial such as myself, a 2002 episode of Aaron Sorkin’s popular political drama The West Wing could still quip that “Death is bad” remained a left-wing position. The scriptwriter took it for granted that, on the political Left, everyone is in favor of human flourishing. If only that were still the case.