American Enterprise Institute

Politics and the Practice of Warm-Heartedness

Brooks blames America’s bitter politics on the “outrage industrial complex”: the media, politicians and commentators who entice voters, attract television viewers, and sell books and event tickets premised on hatred of the other side.

A review of Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America From the Culture of Contempt by Arthur C. Brooks. Broadside e-books (March 2019).

“While politics is like the weather, ideas are like the climate,” Arthur Brooks explains. “However, even a climate scientist has to think about the weather when a hurricane comes ashore… Political differences are ripping our country apart, rendering my big, fancy policy ideas largely superfluous.”

Brooks, outgoing president of the American Enterprise Institute and author of a shopping list of bestselling books, is now taking on the challenging question of how to bring together a divided country. In his latest book, Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America From the Culture of Contempt, he makes the case that Americans are sick of bitter, personal fighting and want a more united nation. The challenge is to work out how to get there.

Brooks blames America’s bitter politics on the “outrage industrial complex”: the media, politicians and commentators who entice voters, attract television viewers, and sell books and event tickets premised on hatred of the other side. These individuals take advantage of “motive attribution asymmetry”: the belief that you are motivated by love and your opponent is motivated by hate. This moral righteousness makes for aggressive conflict. Shockingly, research suggests that Democrats and Republicans in America display similar levels of motive attribution asymmetry to Israelis and Palestinians. In Britain, the conflict between Remainers and Brexiters appears to be reaching similar levels of fury.

The tendency to believe in the righteousness of your own side links closely with New York University professor Jonathan Haidt’s “moral foundations theory,” which identifies how political views are motivated by divergent moral appetites. Haidt found that progressives exclusively prioritize care and fairness, and while conservatives consider these first two moral foundations important, they also value loyalty, authority and sanctity. So it’s not that conservatives don’t care about refugees, they just place greater importance on protecting the nation from perceived danger. Meanwhile, it’s not that progressives want to steal your money and spend it on useless government, it’s that they genuinely care about the poor and believe more government is the solution. In sum, both sides believe they have their views for the morally correct reasons—but those on the Right are marginally better at understanding their opponents because they attach some value to care and fairness, whereas those on the Left often struggle to see the point of loyalty, authority and sanctity altogether.

This sense of righteousness and the associated conflict grows when we only interact with, and therefore only understand, people similar to ourselves. Brooks points to the growing tendency to cocoon ourselves in like-minded social groups and the herding effects of Facebook and Twitter. The lack of exposure to different viewpoints—other than when they are presented in the most negative light—allows us to dehumanise the other side.

Brooks does not just bemoan the state of political debate in America, he explains how to reduce tensions and improve the quality of public debate. The solution, he says, is to remember that your political opponent is not evil and that you and she have quite a lot in common—we are certainly more similar than we are different. “Just because you disagree with something doesn’t mean it’s hate speech or the person saying it is deviant,” he writes. Fundamentally, what we all want is the same: a prosperous, free society, where our kids can go to school safely and have plenty of opportunities, and where our wants and needs are satisfied. You should not just tolerate the other side, you should embrace them, show affection, and be happy that they are there, engaging with you and being part of the discussion. In other words, you should love your enemy.

Easier said than done of course, but Brooks has some tips from the Dali Lama about how to achieve this. “Your Holiness, what do I do when I feel contempt?” he asked him. The Dali Lama responded: “Practice warm-heartedness.” To do so, according to Brooks, it’s important to separate a person from their views. A person’s views might be wrong, misguided or downright evil—but that doesn’t mean the person is. This is much harder online, where a mixture of anonymity and aggression can cause some of the worst human behavior.

Brooks advises us to begin with listening respectfully to other people’s perspectives, be positive and not overly critical, try not to show contempt or hatred, and seek out places where people disagree to build new friendships and understanding. Even if you’re not inclined to do this—and as a loud-mouth, excessively-opinionated over-talker myself, I feel your pain—but making a real effort to follow this style of discussion will, apparently, make you a better person.

To build yourself up, it’s important to find the people with whom you disagree but with whom you share fundamental principles. With these people, you can engage in serious discussions, not with a view to beating them but, rather, building understanding and sustaining an idea in the face of competition. Brooks writes that “if we bring people together and emphasize our common stories, we can discover the new and broader ‘we’ required to overcome mutual contempt.”

This will not only make you calmer, but it will also improve your arguments and even your health, according to Brooks. Those who play the politics of hate do not change people’s minds; they just make both sides more bitter and polarized. In practice, insulting someone makes them more likely to oppose your perspective. It’s better to listen, understand and then try to change minds. Research also suggests that contempt makes you unattractive, unhealthy and unhappy. Nobody wants to be friends with or date a mean person—despite the myth that the mean guy gets the girl.

Identity politics makes it hard to treat people, particularly those you disagree with, as individuals with whom we share common aspirations for a better world. Demographic characteristics can, of course, have a meaningful impact on people’s life experiences and worldviews, but we get little out of focusing on them excessively. Brooks writes that “the key to overcoming prejudice and discrimination is not to double down on what makes people different; rather, it is to undermine prejudice with something more powerful: the empathy and compassion we all naturally feel when interacting with actual people and connecting with them as fellow humans.” Brooks talks about establishing “brigading identity”—that is, finding our common humanity in spite of our demographic differences. This means searching for the shared “why,” not the divergent “what.”

Brooks fills out the book with plenty of cases of what can happen when people who disagree figure out that we are all still human. He discusses Black Lives Matter activist Hawk Newsome addressing a crowd at a pro-Trump rally. What could have turned into a violent mess became a unifying moment when Newsome opened by saying “I am an American” and calmly explaining that he is not anti-cop, just anti-bad cop. Newsome goes on to read from the American creed: “We don’t want handouts. We don’t want anything that’s yours. We want our God-given right to freedom, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The video of the affair has over 2.1 million viewson Twitter alone. This shows, Brooks claims, a real appetite out there for those who want to bring people together.

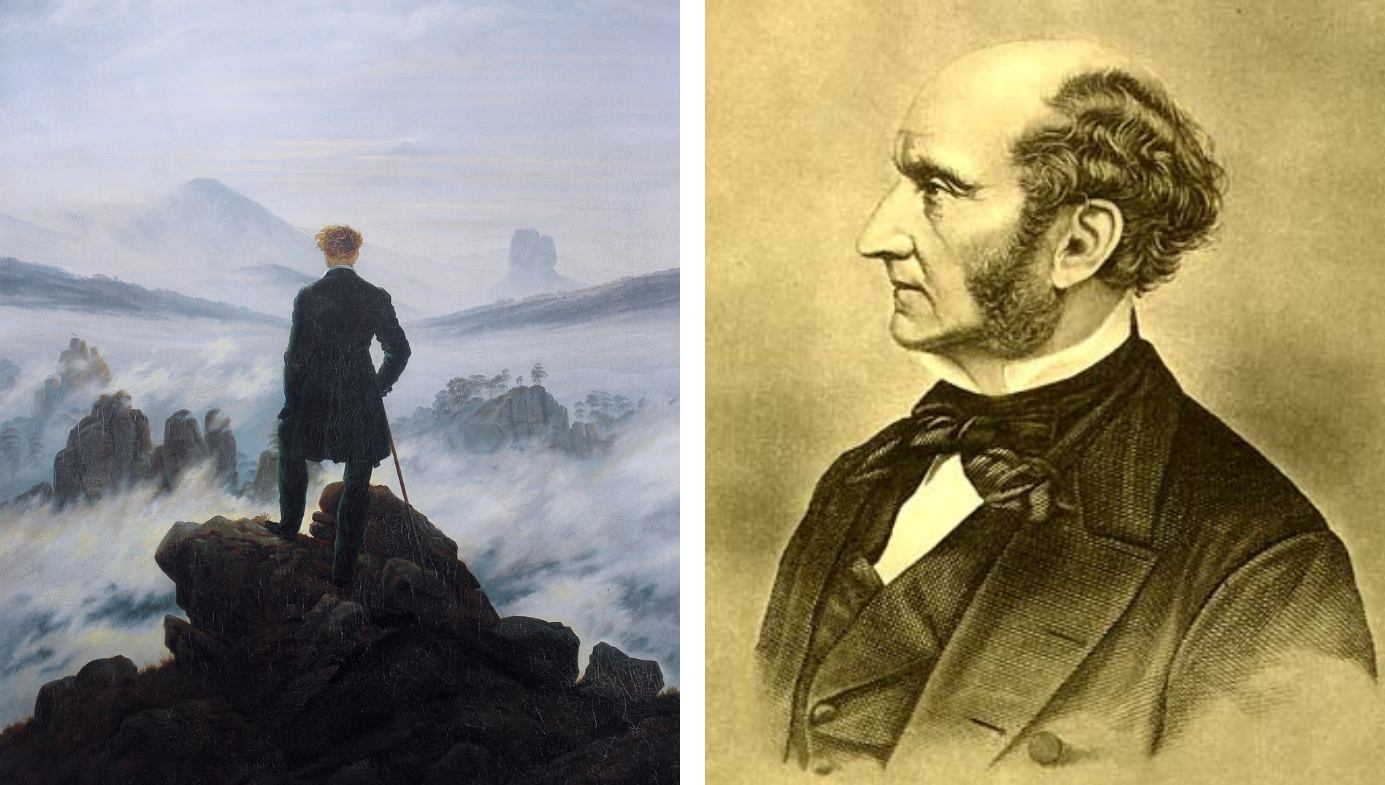

Importantly, Brooks explicitly rejects the popular “centrist” notion that compromise and moderation is the solution. There is nothing virtuous in abandoning your principles. There’s nothing useful about everyone agreeing with each other. What we need to do is work out how to argue better. Competition between different ideas and values is not the problem. In fact, competition fosters and sustains excellence. We should be arguing, in good faith, from a variety of perspectives about the best way to improve society.

Good arguments are essential to humanity’s advancement. As J.S. Mill explained, “It’s hardly possible to overstate the value, in the present state of human improvement, of placing human beings in contact with other persons dissimilar to themselves, and with modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar. Such communication has always been… one of the primary sources of progress.”

Brooks says that “disagreeing better, not less, is what we need to lessen contempt in America and bring our country back together.” We should do this while remembering our shared ends and our friendships and family bonds with those we politically disagree with.

There’s nothing simple about following this approach. It’s much easier to deride your opponent than take her seriously. It’s much easier to dismiss her as a loony rather than engage with her arguments and evidence.

In the end, however, you will be much stronger says Brooks if you can figure out how to love your enemies.