Canada

How Our Little Humanist Club Got Taken Over by Social Justice Dogmatists

It seems wrong that the Executive Director of a humanist association should be able to use his organization’s governing mechanisms to shut down pushback against his publicly expressed ideological agenda.

I love living in this Canada of 2019. Just as it’s okay for my 20-year-old grandson to live with his girlfriend without being married, it’s okay for me to live with mine. No big deal, you say? Of course not. But such arrangements were unthinkable when I was 20 and living in South Africa.

And in this Canada, I can hang with a gay friend and not think of him or her as “my gay friend,” but simply as my friend. And spend time with my other grandson and his girlfriend, who happens to be of South Asian ancestry, and not think of her as “a person of colour,” or “a Muslim,” but simply as the young woman who she is. And no one feels the tension and fear that such a relationship would have produced in the South Africa I inhabited as a young man—where interracial relationships of this type were prosecuted as crimes.

And even though I’m an old white man, I feel at ease and at home in a society that’s moving toward the full emancipation of women, and which recognizes that categories of sexual attraction and gender identity aren’t limited to straight and cis. I used to dream, growing up under apartheid during the 1960s, that there might someday be a time and a place where the law might forbid sexism and racism rather than mandating it. And I have to pinch myself sometimes when I realize that such a reality has come to pass in the place I live.

Freedom from dogmatism imposed by authoritarians also is something I happen to enjoy. In the South Africa of my youth, people didn’t just think that sex and love between “whites” and “non-whites” was wrong. They knew it. And even if they had their doubts, most were inclined to shut up about them: The whole society was built around this evil notion, and there was little room for dissent.

Back in those bad old days, a colleague of mine, an Afrikaner and a member of the Dutch Reformed Church, would end all arguments about apartheid by intoning that “it is the will of God.” And no, he wasn’t joking. In his mind, God was a racist. This was actually a commonly held view.

Later, after we’d both traveled from Johannesburg to Montreal to do graduate degrees at McGill University, I asked him to preface his well-worn words, “it’s the will of God,” with the phrase “in my opinion” if he wanted to preserve our friendship. What could he do? If we’d still been living in the suffocating zeitgeist of apartheid-era South Africa, he might have rejected my request with scorn. But he was lonely in Canada, and wanted to continue visiting with my wife and me, with whom he could speak Afrikaans and drink rooibos tea. So he acquiesced. Old-fashioned thinker that I am, I didn’t ostracize him merely because he held views I found repulsive, since that would have been pointless and inhumane.

Like many of the people who supported apartheid, my colleague was not a bad person—which is why I still tolerated his company. Nor were all of the brainwashed citizens who expressed support for tyrants such as Stalin and Hitler irredeemably bad to their core, either. Ordinary life confronts all of us with wracking dilemmas and painful doubts. Because they purport to offer complete answers, absolutist political systems such as communism and fascism, like rigid and militant forms of religiosity, can hold out comfort to the perplexed. Even in the new, tolerant Canada of 2019, the appetite for such totalizing systems of thought remains strong—even if such appetites are, as described below, expressed in a very different way.

* * *

Regular readers of Quillette need no introduction to the ways in which authoritarian strains of social-justice leftism conflict with traditional liberal precepts such as free speech, rational inquiry and due process. But in most cases, the stories that people read about originate with academics at elite universities such as Yale and Cambridge, or high-profile social-media mobbing campaigns involving influential artists or celebrities. But the struggle is also unfolding in obscure-seeming corners of civil society, where humble little institutions that have existed happily for decades suddenly have come under the thumb of that species of dogmatist that adheres to what I call the Cult of the Woke. This is the story of my own little corner: the Vancouver-based British Columbia Humanist Association (BCHA).

The BCHA was incorporated as a nonprofit corporation in 1984. It meets on Sunday mornings at a seniors centre, where we listen to invited speakers and discuss all manner of intellectual subjects, typically with a focus on secular values. As with many humanist groups, our membership exhibits a healthy suspicion of anything that smacks of religious dogma, and which interferes with the traditional humanist approach of pursuing rational inquiry and communication. Unfortunately, this approach flatly contradicts the social-justice approach to truth-seeking, which, in ersatz religious fashion, presents many of its precepts as a form of revealed truth; and which casts unbelievers as unworthy heretics.

Alass, this latter social-justice approach has been embraced fully by BCHA’s current Executive Director, Ian Bushfield, whose actions have pushed a wonky little group of weekly seminar attendees into full-on drama. Indeed, Ian recently expelled Joann Robertson, a past BCHA President and long-time member, when she expressed concerns about what she regarded as an ideologically motivated warping of BCHA’s long-time mandate.

The bad blood rose to the surface when the editor of a small publication called Humanist Perspectives authored a firebrand column with the admittedly provocative title Social Justice: The New Totalitarianism? Using his personal Twitter account, Bushfield dismissed the article as “garbage.” Bushfield (whose email signature informs correspondents that he is “working on unceded Coast Salish Territory—shared lands of the xwməθkwəyə̓ m (Musqueam), Skxwú7mesh(Squamish) & səlilw̓ ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples”) then went further, and wrote a column attacking the piece, which he included in a BCHA newsletter. Alongside a Grampa Simpson cartoon meme presumably meant to disparage the author’s age and the unfashionability of her views, Bushfield accused the Humanist Perspectives editor of being “transphobic and contemptible,” among other throughtcrimes.

The Humanist Perspectives editor should be free to write what she thinks—even if I, or others, don’t agree with all of it. Bushfield, likewise, should be completely free to voice his own opinion—so long as he takes pains to note that he is speaking in his personal capacity and not as a BCHA official, which, to be fair, he did in his column. Bushfield is also free to tweet things like “Fuck Jordan Peterson,” to denigrate free-speech supporters as “garbage-eating scavengers,” to denounce classical liberals as “sinister” operatives who promote Nazis and Islamophobes, and to repeatedly denigrate “old white men”—even though there are plenty of people who are old, and white, and male in the organization he leads.

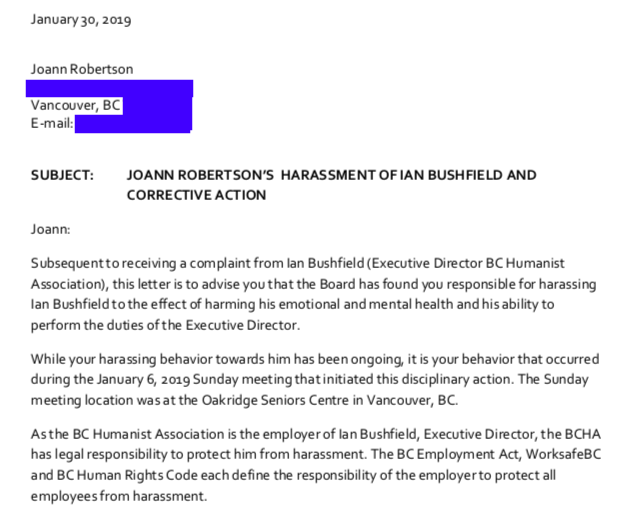

Rank-and-file BCHA members should have the right to voice their own opinions, too. But that seems to be a problem for Bushfield. At a January 6, 2019 meeting, longtime BCHA member Joann Robertson rose to take issue with Bushfield’s attack on the editor of Humanist Perspectives. Robertson’s comments were relatively mild. The only “harassing” comments from this meeting that Bushfield cited in a January 30, 2019 memo grandly titled “JOANN ROBERTSON’S HARASSMENT OF IAN BUSHFIELD AND CORRECTIVE ACTION” were that he makes “anti-humanist statements [and] this is what a lot of people in this room don’t realize because they are not online,” and “People in this room need to know your true humanist values.” But according to BCHA president Dan Hanna, who signed the letter, such comments had the effect of “harming [Bushfield’s] emotional and mental health and his ability to perform the duties of the Executive Director.” Bushfield, Hanna claimed, had been “defamed,” “harassed” and “belittled.”

As punishment, Robertson was ordered to “provide a written apology to the BCHA Board and deliver a public apology at a Sunday meeting to Ian Bushfield that acknowledges that you did harass him at the January 6, 2019 Sunday meeting…In the event that you do not provide the apology as described above, the Board of Directors has authorized your expulsion from the BC Humanist Association membership.” Obviously, no such apology was forthcoming, and Robertson was duly expelled.

The BCHA is a private organization that can pretty well do what it wants—so long as such actions are consistent with provincial legislation governing non-profit entities and its own constituent documents, and are approved by the Board of Directors (which now seems to be taking a highly co-operative approach with Bushfield). But it seems wrong (and possibly unlawful in the bargain) that the Executive Director of a humanist association should be able to use his organization’s governing mechanisms to shut down pushback against his publicly expressed ideological agenda. The entire history of the humanist movement, and of the Enlightenment that gave rise to it, is the story, after all, of the discussion of new and uncomfortable ideas. Robertson and her allies in the BCHA don’t just have the right to speak up about Bushfield’s leadership. As humanists, they have a duty to do so.

I realize that all of this must seem almost comically quaint to readers who are more used to discussions about intrigues at Ivy League universities and such. But our locally rooted organization—and the many thousands of others like it—play a huge role in the intellectual lives of ordinary people. And they generate strong feelings of loyalty. Robertson has many supporters in the BCHA. And, on February 2, three days after she received notice of her expulsion, one of them, Sigal Blay, sent out a notification that she and others were intending to requisition a special meeting under the Association’s bylaws to discuss both Robertson’s expulsion and Bushfield’s tenure as Executive Director.

If you have worked in a political party or any similar entity whose leadership is being challenged, you might guess what happened next. Two days later, the BCHA issued a newsletter announcing—surprise, surprise—a new $3-per-month membership plan, plus a 75% discount on the usual $40 lump-sum fee paid annually. On February 7, a tweet from Bushfield followed, announcing that 30 new members had been recruited in the preceding four days. All of them are eligible to vote on any new business that might emerge. How about that.

In theory, both sides can play at that game. But a few weeks later, after clicking the “Become a Member” button of the BCHA website, one of the Association’s members accidentally discovered that—as the site put it—“membership applications are temporarily closed pending a review of our membership policy by the Board of Directors.” Have you ever heard of any locally organized civil-society group of this type that wasn’t taking new members, let alone membership applications? Me neither.

It’s not known when or why that freeze on new members was put into effect—though it’s not hard for me to guess. All attempts to gain access to the membership list and minutes of previous board meetings now are being met by apparent obfuscation and delay. The special meeting requisitioned by Robertson’s friends is still on for April 15, but one has to wonder whether anything will come of it in light of these apparent machinations.

If this were one of those Netflix series about life in a small Scandinavian town, I’d binge-watch it to see how all of this plays out. But it’s real life, so I’m going to have to remain in suspense. Whatever happens, I suspect that our little skirmish will fade quickly from any wider attention we may receive. But the larger phenomenon that lies behind this conflict will not fade quickly. The fight over the future of the BCHA is part of a larger struggle for the soul of civil society waged between liberals and a new breed of authoritarian-minded dogmatists. And it isn’t for me to identify which side represents the true face of humanism—and of my own beliefs.