recent

Prescriptive Racialism and Racial Exclusion

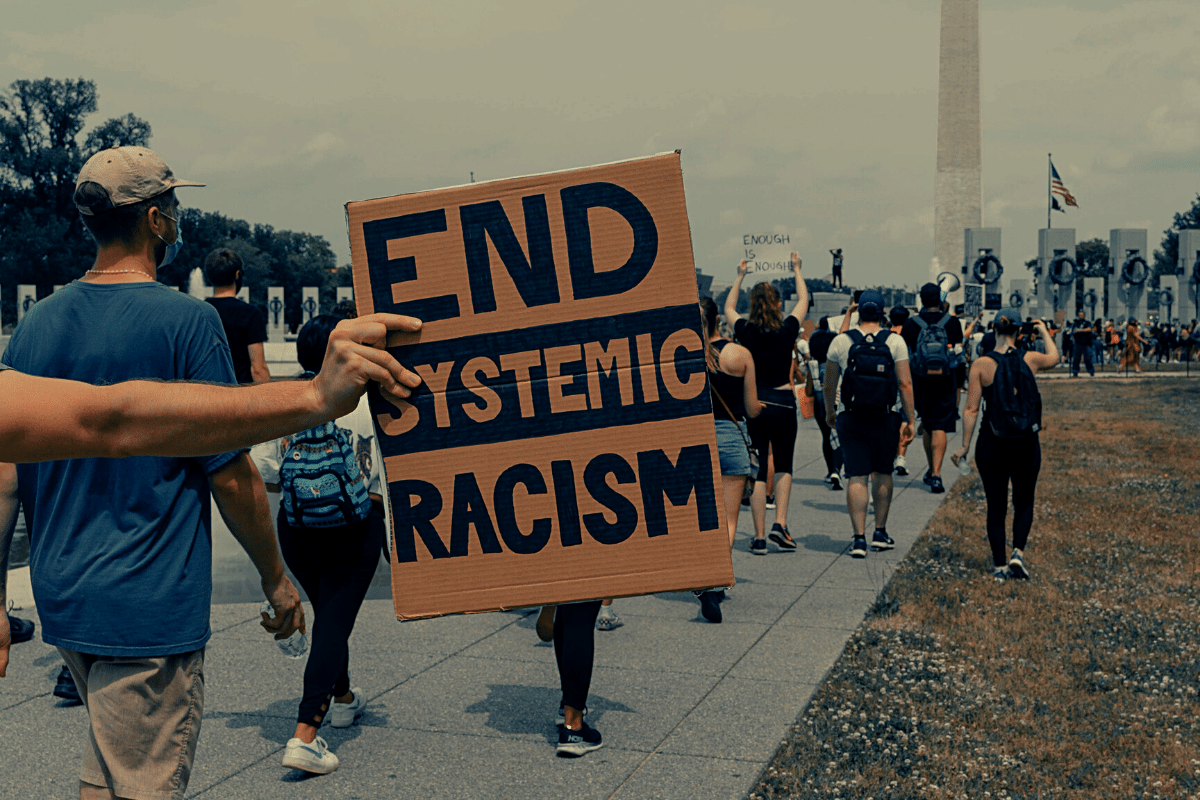

Today, it has become central to the worldview of many on the social justice Left.

The crowd outside the auditorium was growing larger and louder. Controversy had arisen over the “Panel on Religious Extremism in the Middle East” that I had organized at my University. A petition to cancel the event in the wake of the horrific New Zealand massacre had been circulated among the student body during the previous week, forcing my co-organizers and me to defend ourselves against accusations of Islamophobia. Months of work had gone into the event, and I had even managed to secure funding for the speakers, on the condition that the event went ahead. At that moment, it looked like I was going to fail. The Students for Democratic Society were protesting and they spooked the president of College Republicans who was now considering cancelling it.

Finally, one of our panellists—an Imam—managed to persuade the College Republican president to go ahead. Despite the constant heckling during the speakers’ remarks and the Q&A session that followed, the event did finally proceed more or less as planned. The panel and I addressed the New Zealand atrocity and explicitly condemned White Nationalism, but the protestors remained unmoved, and even interrupted the moment of silence for the massacre’s victims. Throughout the event, they held a banner that read, “You Do Not Represent Us.”

After the event I overheard a student protestor berate one of the panellists and complain, inter alia, that the event had not been organized by an Arab. I interjected to inform her that I was the organizer of the event and that I am indeed an Arab. “You don’t count,” she immediately retorted. “We know your politics.” I subsequently discovered that she is president of the Arab student association. I was already aware of this practice of “Uncle Tom-ing” members of minorities who challenge certain orthodoxies, but this was the first time I had experienced it firsthand. Such attitudes were evident in many of the protestors’ objections to the event. Faisal Saeed Al Mutar—an Iraqi born secular rights advocate and the only Arab on the panel—bore the brunt of these attacks. He was denounced as a puppet and a traitor for discussing the role of religion in motivating groups like ISIS in his native country.

Particularly distasteful was the insinuation that race is not simply a descriptive category, but that it is thought to require certain duties of, and impose certain prerogatives upon, the individual. To retain one’s status as an “authentic” Arab (or member of any other “marginalized” demographic), one has to believe certain things. Because I had organized this discussion, I was rendered persona non grata among those who insist we turn a blind eye towards atrocities committed in the name of Islam. Investigating this matter at all apparently constituted a betrayal of my tribe, the punishment for which is excommunication. I’ve come to call this attitude “prescriptive racialism”—the notion that racial identity should determine how people act and what they believe. To be accepted as an Arab, I must adopt the same politics as all other Arabs.

This belief dominates the paranoid psychology of white supremacists, who are similarly pre-occupied with the idea of race treachery. Today, it has become central to the worldview of many on the social justice Left. And, as I discovered, prescriptive racialism is enforced by racial exclusion. This practice is a troubling development, and another sign of civic disintegration along ethnic lines. Racial exclusion ostracizes (or “others” in social justice jargon) the heretics within a community who challenge its dogmas: “Fall in line or you are out!” This is hardly an empty threat. In our polarized and balkanized society, people are already clustering into increasingly narrow groups organized around sexual, racial, and other immutable identities, so exclusion can be politically hazardous. Racial exclusion awards permission for the harassment and degradation of its victims, and strips dissenters of a voice: “You are no longer one of us, so you do not get to criticize what we do.” This is the language of primitive chieftains from the iron age, unfit for a modern republic in which reason should be free to criticize any injustice it encounters.

In a free society, we must commit to persuasion if we want to change minds. But how is that possible if the ideas of those who do not belong to a minority group are ignored and critics within that minority group are shamed and summarily expelled? Progressive culture screams platitudes of coexistence, tolerance, and multiculturalism even as it undermines the values that make those things possible. If toleration and coexistence are mocked by critics as vacuous cliches, it is because their defenders no longer take them seriously or bother to defend them.

In a 2015 article for the Guardian, Al Jazeera journalist Mehdi Hasan lamented the “lazy calls for an Islamic reformation from non-Muslims and ex-Muslims.” But if ex-Muslims have their criticisms denigrated in this way, not because of what they say but because of who they are, what hope is there for ending the lethal punishments for apostasy across the Muslim-majority world? If being outside of a group precludes someone from criticizing its members or its doctrines, then what are we to do when those members commit injustices against outsiders?

The dangerous and sectarian practice of prescriptive racialism is an outgrowth of an insistence that we think of people not as individuals but as representatives of groups—we speak of “the Arab experience” as if it were a uniform phenomenon. In a world in which groups are considered more important than people, it was inevitable that we would forfeit the ability to think in terms of unique human beings, each of whom may fall into several categories, but who are ultimately self-made characters. We should remember that the important features of an individual are what they choose to be and not the identities they happen to have inherited.

Defeating this rising tide of tribalism requires us to be adamant about the importance of the validity of ideas and criticisms and not their source. When the protestors raised the banner which read “You Do Not Represent Us” what they really meant is “We Do Not Consider You One of Us, So What You Say Is Worthless.” The Islamic philosopher Al Ghazali did the same when he railed against the Greek pagan influence during the Islamic Golden Age, and in doing so he extinguished the brilliant flame of scientific thought of his era. The Middle East has been dark ever since. When someone like Faisal Saeed Al Mutar attempts to reignite it by translating Western works into Arabic, he is met with antagonism and exclusion—not from an intellect like Al Ghazali, but from sanctimonious second-generation Arab students living in upstate New York. These are unworthy opponents of such a magnificent project.