Education

Free Speech for Me, But Not for Thee

How can students advocate for speech codes and still believe that freedom of speech is secure?

Many people who genuinely believe that they support freedom of speech exhibit a double standard: One person’s “hate speech” is another person’s belief, opinion or even (as they see it) fact. And opinions about whether there’s a “free speech crisis” on university campuses tend to vary according to these subjective determinations.

While I’m not a fan of such “crisis” language, there’s definitely a real decline in support for freedom of expression among young people. In a 2016 Knight Foundation survey, 91% of high school respondents said they supported the “freedom to express unpopular opinions.” But when pressed, only 45% said that people should have the right to publicly express ideas that others find “offensive.”

The Knight Foundation’s numbers on college students’ attitudes are similar. In 2016, 78% of college respondents agreed that colleges should expose students to all types of speech and viewpoints. Yet, more than two-thirds said that colleges should be able to enact policies against language that is “intentionally offensive to certain groups,” and more than a quarter said that colleges should even be able to restrict the expression of potentially offensive political views. (More than half reported that the climate on campus “prevents some people from saying what they believe because others might find it offensive.” A year later, that number rose to 61%.)

This data is consistent with a 2017 survey conducted by my employer, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), whose mission is “to defend and sustain the individual rights of students and faculty members at America’s colleges and universities.” In that survey, more than half (58%) of college students agreed with the statement, “it is important to be part of a campus community where I am not exposed to intolerant or offensive ideas” (my emphasis). When the same question was asked a year later, the proportion rose to 64%.

Embedded in such data is evidence of the common double standard in this area: Notwithstanding the survey results cited above, 73% of college respondents in the 2016 Knight Foundation survey said they were confident that freedom of speech is secure or very secure. How can students advocate for speech codes and still believe that freedom of speech is secure? The answer, as an intern at the liberal Center for American Progress (CAP) put itin 2017, is that “most college students do not feel that the anti-hate movement puts their [own] right to free speech under attack” (my emphasis). That is linked to the mistaken idea that (to quote George Lakoff), “hate speech is not free speech.” Or as that aforementioned CAP intern put it, hate speech—however that term may be defined—is “outside the bounds of free speech.”

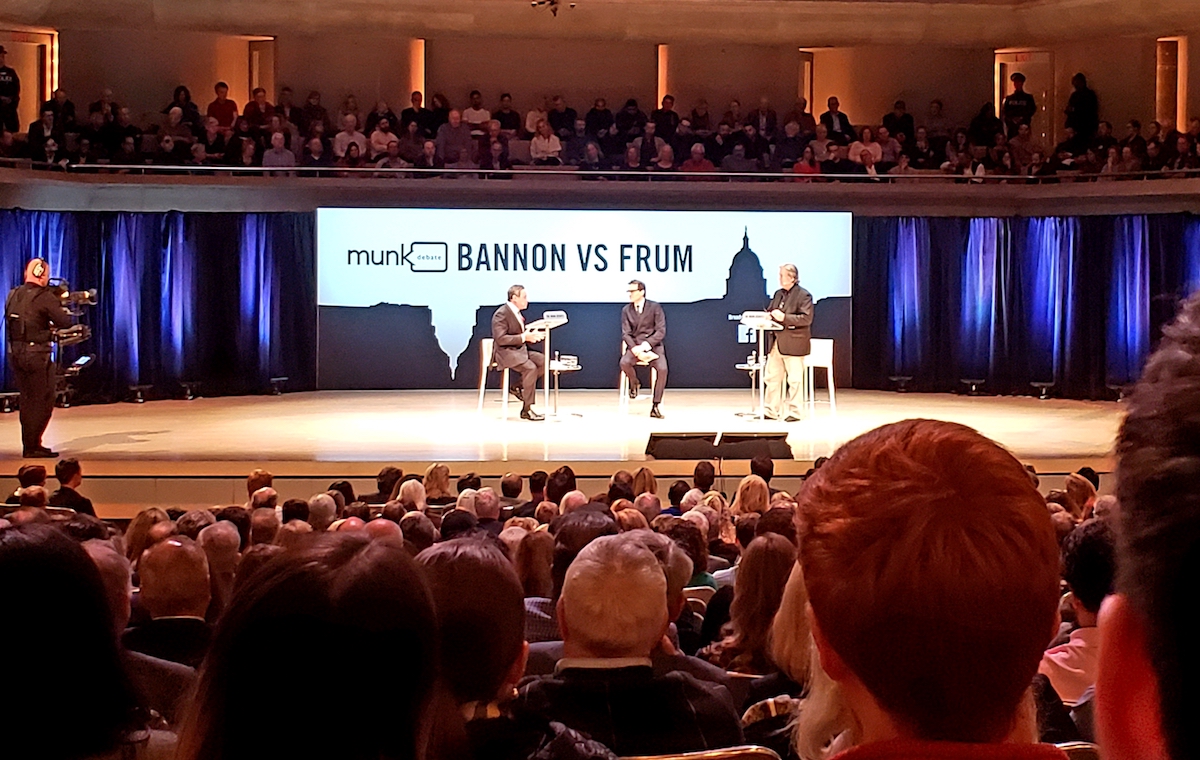

But if we stop protecting anything that people call “hate speech,” then the location of those “bounds” becomes subjective. In 2018, when former Donald Trump strategist Steve Bannon was scheduled to speak at the University of Chicago, more than 100 faculty members signed a petition demanding that he be disinvited, arguing that the campus should be an environment where “hate speech…is not tolerated.” Professor Emeritus Jerry Coyne responded by calling for “a broad endorsement of free speech and condemnation of those who would ban or de-platform speakers.” After reading Coyne’s statement, a commenter proclaimed on Facebook, “this is not about free speech; it’s about fascist speech.”

A related tendency is that some de-platforming advocates now condemn those who defend the right of controversial speakers to be heard. They contend that defending freedom of speech is a cover for promoting hate speech (as they define it)—even arguing that speech is violence. After the violent riots that forced the cancelation of a 2017 talk by right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, for example, some defended the physical violence as self-defense against the metaphorical violence of Yiannopoulos’ words. One student declared, “if you condemn the [violent] actions that shut down Yiannopoulos’ literal hate speech, you condone his presence, his actions and his ideas.”

A recent campus controversy provides a telling example. After the January, 2019 murder of police officer Natalie Corona, a student at the University of California, Davis browsed Twitter to investigate rumors about a UC Professor, Joshua Clover, having “advocated for violence against law enforcement.” The student published what he found in The California Aggie, including Clover’s statements that “I am thankful that every living cop will one day be dead, some by their own hand, some by others, too many of old age #letsnotmakemore” (Twitter, Nov. 27, 2014); “I mean, it’s easier to shoot cops when their backs are turned, no?” (Twitter, Dec. 27, 2014); and “People think that cops need to be reformed. They need to be killed” (interview; Jan. 31, 2016).

When the student journalist asked Prof. Clover to comment, he responded, “I think we can all agree that the most effective way to end any violence against officers is the complete and immediate abolition of the police,” and directed “any further questions to the family of Michael Brown,” the 18-year-old African American man whose 2014 death at the hands of police officers set off riots in Ferguson, Missouri.

The school’s chapter of College Republicans held a “Fire Josh Clover” rally that drew about 100 people. One student sought institutional condemnation and sanctions, claiming—much in the same spirit as the Berkeley students who protested Yiannopoulos—that the professor’s words were “violent.”

For its part, FIRE wrote to the Chancellor of UC Davis to remind him that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution “limits the disciplinary consequences that a public university may impose on a professor for speech expressed in his private capacity on matters of public concern—including unpopular or widely condemned comments about law enforcement.”

But California Assemblyman James Gallagher (a Republican who got his law degree at UC Davis) asserted that the professor’s comments amounted to an incitement to violence and were therefore not protected by the First Amendment. He called for Clover to be fired, presented a petition with 10,000 signatures, and even introduced a House Resolution “to remove Professor Joshua Clover from the classroom and terminate his employment at the University.” Echoing those who protested Bannon’s appearance at the University of Chicago, he insisted, “this is not about free speech or academic freedom.”

Initially, the university responded by recognizing the professor’s First Amendment rights. But after Gallagher got involved, the university’s press team indicated that an investigation was underway and that the administration was “working very hard to address this matter.”

Gallagher’s assertion that Clover’s speech was unprotected is incorrect: The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1969 decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio set an extremely strict standard for censorship in cases such as this. And so FIRE called for the university to cease its investigation. In Brandenburg, noted Sarah McLaughlin, FIRE’s Senior Program Officer, Legal and Public Advocacy, “the Court held that the state may not ‘forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.’ In other words, there is a difference between hypothetically wishing people would die, which is protected speech despite the offense it may cause, and a call to action that’s likely to result in violence, which is not protected.”

The intervening years since Clover’s tweets and interview—during which nobody acted on his views—evidence that his statements were not likely to produce the “imminent” response required to remove First Amendment protection. “Because rhetoric tinged with violent themes often overlaps with charged political expression,” explained McLaughlin, “the First Amendment requires a high standard to be met before a statement constitutes unprotected ‘incitement.’” The university responded by telling FIRE that (thankfully) there will in fact be no investigation.

* * *

In the heat of the moment, people say (or tweet) all kinds of things that others find entirely reprehensible. But abundant empirical evidence indicates that we are all prone to judge the people whose ideas we dislike more harshly than the people whose ideas we like. And so we must all remember that when we defend freedom of speech, it is not ideas or people we are defending; it is the freedom itself.

This is why real free speech advocates so often refer to Evelyn Beatrice Hall’s description of Voltaire’s perspective: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” For anyone who decries the censorious culture on campus, the treatment of Joshua Clover presents the ideal opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to freedom of speech rather than the freedom to express particular views. And for anyone who thinks that a line must be drawn at the place where speech offends or could be considered harmful, the contrast between the “harmful” speech in this case and other high-profile cases illustrates why we cannot move that line away from where the Supreme Court has already drawn it.