China

China is Gearing up for a Long Fight

If China is responsible for the attack on the Australian parliament, the intelligence that it has gathered could be very useful in eroding the appeal of democracy worldwide.

On February 18, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that a “sophisticated state-actor” had launched a cyber attack on Australia’s major political parties and parliamentary computer system. The Australian government has not yet identified which state-actor is responsible but suspicions almost instantly fell on China. The Chinese military maintains a dedicated unit (the People’s Liberation Army Unit 61398) for cyber attacks. While several other nations maintain the capabilities for this kind of attack, they do not have China’s record of interference in Australian politics. The Chinese Communist Party puts significant resources into neutralizing opposition to its interests within Australian politics and society. Its increasingly flagrant acts of interference prompted the nation to pass sweeping foreign interference laws in 2018.

If China is responsible for the cyber-attack on Australian parliament, it fits a very clear pattern of increasing antagonism by China against the West. This points towards a worrying and unstable future for Western middle-powers with high economic exposure to China. Moreover, China’s increasingly threatening posture suggests that it no longer believes that it can radically reshape the international order without waging a long-term strategic conflict with the West. Until recently, China was careful to maintain the West’s support for the nation’s rise by refraining from activities that would trigger too much anxiety. Not only is China now engaging in these activities with little pretense of restraint (including militarizing the South China Sea) but it has gone one giant leap further by directly threatening the autonomy and stability of Western societies with extensive interference operations.

Central to the Chinese government’s efforts to meddle in Western societies is the United Front Work Department, a Chinese Communist Party agency tasked with promoting Beijing’s interests abroad by co-opting key elites and organizations. A 2018 report published by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (based on an academic outreach workshop held by the agency) emphasized the magnitude of China’s efforts to interfere in democracies, with New Zealand and other small states being the most vulnerable. The report states:

New Zealand provides a vivid case study of China’s willingness to use economic ties to interfere with the political life of a partner country. An aggressive strategy has sought to influence political decision-making, pursue unfair advantages in trade and business, suppress criticism of China, facilitate espionage opportunities, and influence overseas Chinese communities. Smaller states are particularly vulnerable to Chinese influence strategies.

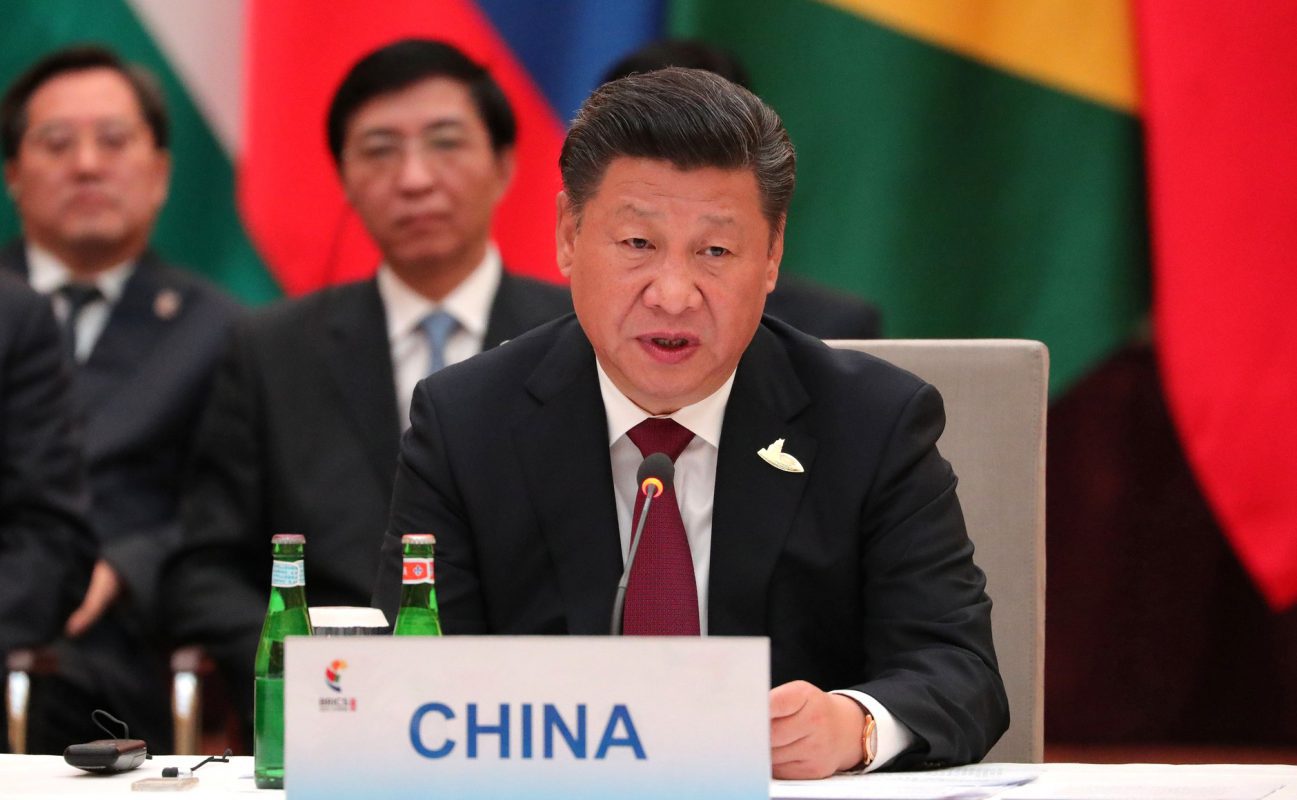

While China’s use of foreign influence operations is not new, President Xi has taken them into wholly new territory. Dr. Ann-Marie Brady, a political scientist at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, said she was the victim of a year-long intimidation campaign within New Zealand after publishing her research outlining the Chinese Communist Party’s strategy of interference in Western democracies. Brady believes the intimidation campaign was directed by the Chinese government and says that her home was raided, her car sabotaged, and her office broken into.

If the Chinese Communist Party believed that it could use this kind of coercion to suppress certain kinds of speech on New Zealand soil without significantly impacting bilateral political and economic relations, it likely means two things. First, it suggests that China’s United Front Work in New Zealand is highly successful. Second, it implies that New Zealand is so reliant on economic activity with China that it wouldn’t protest the Chinese Communist Party’s aggressive incursions into the country.

China’s attempts to manipulate Western societies are increasingly felt across the media landscape, as well. On February 19th, The New York Times reported that producers of the film “Berlin, I Love You” scrapped a segment directed by Chinese artist and political dissident Ai Weiwei. The film’s distributors, producers, and investors raised concerns about Ai Weiwei’s political sensitivity to the Chinese government. In response, Ai Weiwei said, “It shows the extent to which China has used its power to influence the West in every aspect.” China’s “censorship” capabilities in the West stem from the extent of Chinese investments in Western media as well as the pressure on companies to maintain access to the enormous Chinese market.

Lastly, China’s growing assertiveness towards the West can also be seen during diplomatic spats. China is increasingly using strong-arm tactics against middle-power security allies of the United States. Following the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Canada on December 1, 2018, China detained 13 Canadian citizens, in an attempt to pressure Canada to forsake its independent judicial process and release Meng Wanzhou.

Ultimately, Beijing’s chilling influence in the West is a consequence of extensive economic integration with China. Western countries opened the door to unwanted influence from Beijing by so widely exposing their economies to China and effectively tying their prosperity to a political relationship with the Chinese Communist Party. This may not have seemed unwise when China was growing increasingly liberal (albeit from a very illiberal starting point) and friendly towards the West.

Today, a very different China understands that it can now force these countries to choose between their own prosperity and other national interests, including (as we’ve seen from recent episodes) the security of national telecoms networks, freedom of speech, and respecting an independent judiciary. Given that politicians’ reelection prospects depend on the state of the economy, the choice will often be in the Chinese Communist Party’s favor and Beijing’s vision of “global win-win economic cooperation” will prevail. In this way, China understands how it can use nations’ democratic institutions against them. When linking their economies with China, the West understandably, but naively, failed to process the possibility that one day, given a different political landscape, the Chinese Communist Party might seek to use its economic gravity to reshape the world, just as it is now doing.

In some sense, China’s growing assertiveness towards the West at this juncture is puzzling. Despite what Chinese education and state-run media has been telling its citizenry for decades, the West has been remarkably open to China’s rise, relatively forgiving of its long history of human rights abuses, and open-minded about the country’s unique governance needs (i.e. absence of democratic institutions and weak rule of law). China’s behavior in recent years has rather forcefully confirmed the suspicions of the West’s China hawks and increased their sway. Some American officials that unsuccessfully advocated against economic integration with China in the 1990s have risen to positions of influence with a mandate to undo the economic relationship, and have already had a surprising amount of success (hence the Sino-American trade war). Why would President Xi Jinping seemingly squander the goodwill that helped nurture China’s meteoric rise?

China’s increasingly threatening posture towards the West would not be so costly for China if it were turning inward at this time. But China is charging ahead in its ambitions to reshape the global economic order and build national champions to conquer the commanding heights of the global economy. Unless one believes that China’s rise is inexorable, surely these goals, already challenging, become astronomically more so when other national powers are routing against the country, let alone seeking to contain it.

China’s decision to take a more threatening posture towards the West likely comes from a deep understanding in Beijing that it will end up in a protracted struggle with the West, one that will dominate the global security environment for decades to come. Through gathering intelligence within democracies, co-opting elites, and making disengagement from China as painful as possible by flooding nations with investment while it still can, it can begin the fight with a better hand. China has also successfully sought to delay the West’s realization of hostilities through its rhetoric of “win-win ties” and President Xi’s portrayal of himself as globalization’s knight in shining armor.

If China is responsible for the attack on the Australian parliament, the intelligence that it has gathered could be very useful in eroding the appeal of democracy worldwide. It could use such attacks to create chaos within the country and incite public doubt in Australian institutions. After all, a long-term struggle between China and the West will be, in part, a contest over which form of government works better. This will be an ongoing concern for Western democracies, even if it turns out that another state-actor was behind the cyber attack on Australian parliament.

There is, of course, an argument to be made that China has taken this new, more threatening posture not because it is preparing for a protracted strategic conflict with the West, but because it no longer needs the West’s acquiescence to reshape the global order. According to this idea, China power has already grown so great that it does not need to be concerned about the Western backlash against its ambitions. However, if this were the case, China wouldn’t find it nearly as important to conduct such extensive influence operations in the West, which require considerable financial resources.

This argument also breaks down when looking at China’s current ability to shape outcomes in global affairs. China might be pulling ahead in a number of tech races, but its comprehensive power capabilities are not yet great enough to reshape the global order using brute force alone.

Consider that China has only one treaty ally: North Korea. The U.S. has more than 60 (granted, many are dubious at this point). Of course, China’s lack of treaty alliances is partly due to national policy, and is not solely due to ineptitude at making friends. Additionally, economic clout may be a far more important indicator of global influence in the 21st century. Nevertheless, the disparity in security relations indicates a disparity in the ties and trust that the world has with China. All else being equal, China’s recent actions in the West will only increase that disparity.

Putting international relations aside, what is occurring within China today may provide an even better indication of China’s ability to reshape the global order, given a West that is increasingly hostile to China’s global ambitions. Since 2012, the world saw China comprehensively shift towards neo-totalitarianism and commit cultural genocide against its Muslim citizenry. It is difficult to imagine that China’s leaders believe that the West would find the global dominance of this China even remotely palatable. What happens within China’s borders reflects the mindset and values of the government.

If China is now acting this way within its borders and is already acting this aggressively towards the West, the world might not wish to see how China would act if its national power dwarfed all others.