Art and Culture

Lessons From a Recovering Identity Warrior

Its associated victimhood mentality, and the culture of (now state-sponsored) weaponized sensitivity that this mentality has incubated.

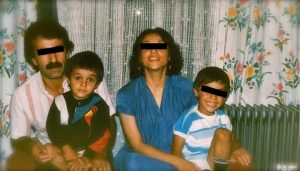

In 1988, my family fled Iran to seek political asylum in Canada. I was 5 years old. When we arrived, we did what all desperate immigrants from war-torn countries do: We found our ethnic enclave and surrounded ourselves in it as much as possible to help ease the transition.

During these years, I thought I was the default, the norm. That is to say, I thought I was white.

Almost all of my friends were Iranian. We ate the same food, pronounced each other’s names correctly, and our parents spoke the same language at home. I never had to deal with any racial tensions at all. All of the other ethnic groups at school—the Tamils, Latinos and Jamaicans—did the same. Everything fit.

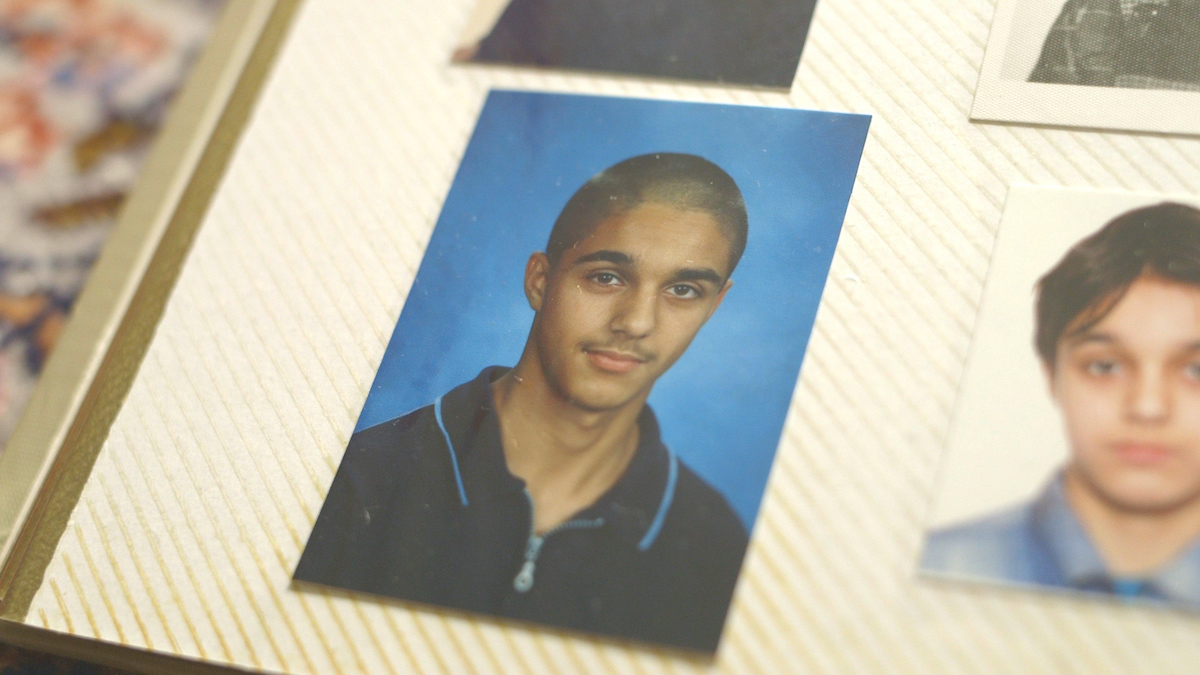

My ethnic identity wasn’t something I thought much about. That was until we moved from the multicultural milieu of Scarborough (a suburb of Toronto) to Burnaby, British Columbia, when I was 11 years old. My new school featured only one other set of Iranian siblings amidst a sea of white and Chinese kids.

I was bullied frequently. Sometimes, this was because a popular girl liked me for a week. But mostly it was rooted in sheer ignorance—for instance, because I ate “weird brown sauce” called curry that “smelled funny.” (In fact, I didn’t even know what curry was. It’s not part of Iranian cuisine.) Suddenly, I knew I was different.

While watching The Simpsons with friends, I would recoil when Homer would visit Apu at the Kwik-E-Mart, bracing myself for any lazy taunts that his appearance might prompt. My white Canadian friends didn’t really distinguish between Middle Easterners and South Asians. It was confusing because I didn’t know anything about Indian culture. I just knew it wasn’t desirable to be associated with it.

(Even within the regressive sectors of my own Iranian culture, one of the worst things to be called is a Hindu or a “Paki”—almost as bad as being mistaken for an Arab. As I grew up, I found it interesting to see how white liberals always seemed to give a free pass to people of colour who cruelly, and quite openly, exhibited racism toward one another.)

There’s a scene in the 1995 movie Casino where one of Joe Pesci’s goons buys black-market jewellery from “sand-niggers” who speak Farsi. I’d thought I was white—and yet now I was black (or, at least, “black-adjacent”). The occasional rerun of a Chuck Norris film featuring herds of shrieking, angry villains with mascara eyes and bushy eyebrows wearing rags and toting AK-47s didn’t do much for my self-esteem, either (though at least these movies tended to get their geographical references right).

I was always smaller than the other kids at school, and kept my defences up by being a sharp-tongued little prick. With the Chinese bullies, this worked fine. But when it came to racist jibes from whites, I found it difficult to offer silencing comebacks. What could I say? “Hey Brody, you look just like an older version of that Home Alone kid who’s such a popular box-office draw!”

I didn’t have the tools to deal with my emotions appropriately. No other kid looked like me, and I didn’t want to trouble my overworked parents with any of my anxieties. They were too busy trying to inch out of welfare. And anyway, I doubted whether they’d be able to understand my situation, let alone help me fix it.

As I got older, I became attracted to the more ethnocentric elements of my ancestral culture. As a shortcut to show strength—or at least avoid the appearance of weakness—I learned to play the “race card,” which at first I used in a strictly defensive capacity. In a game that centred around power, I quickly learned how to play the hand I was dealt—for I now could leverage political correctness to put myself atop another kind of racial hierarchy. Without realizing it, I was exercising my own version of racism.

Yet I was no “snowflake.” Like many boys, I was attracted to the idea of gangs, violence and crime. I even sold mushrooms and pot during high school, and ended up getting suspended at one point. My marijuana-enhanced fantasies of being strong and dangerous felt more real when we visited cousins in Los Angeles. They told me stories about local ethno-criminal gangs such as Persian Pride, and I loved the associated image of strength and unity such names were meant to convey. I also loved to hear historical stories about how the Persians once had the largest empire on the planet. I became addicted to the sugar high of pride that came from other people’s achievements.

It’s normal to want to be proud of your heritage, especially when you’re part of a minority group that you don’t see reflected back within the larger culture you inhabit. But there’s a reason why many religious traditions treat pride as a sin: It usually doesn’t end with an innocent fondness for a flag, or a symbolic salute to a dead president or king who resembles that beloved grandfather you’d never met. Pride can easily push you into one-sided distortions of history.

One example of this is the drunk-dad-level conspiracism I parroted in regard to the 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran, whose 40th anniversary passed this month. I told everyone that the revolution was entirely a Western plot to undermine Iran’s sovereignty and development, even though I knew little about geopolitics. While it doesn’t tell the whole story, my claim wasn’t completely ludicrous, given the long history of cynical and deadly U.S. intervention in the internal politics of developing nations during the Cold War—from Egypt to Brazil to Indonesia to Iran itself. But history is complicated, and I had fallen into the trap of attempting to distill world events down to a simplified morality play. My goal was psychological: to extinguish shame and promote a collective paper-tiger pride.

My campaign of resentment raged on in odd, self-contradictory ways. I began to turn down the volume on Iran’s Islamic history and amplified its Western-friendly qualities such as paisleys, pistachios and pretty eyes. I referred to myself as Persian rather than Iranian, yet I still reminded everyone within earshot that the word Iran comes from “Aryan”—a silly attempt to whiten my own culture even as I expressed resentment at white, Western imperialism.

Blaming America for the backwards nature of my home country felt right to the resentful teenager I then was. And even as I grew older, my lefty (white) friends never called me out on it—even when I wasn’t making sense—because I was railing against The Man. I was punching up. Who needs facts, when you have a nodding, guilt-ridden white ally to vent to? It was like a woke intellectual masturbation session that offered a symbiotic catharsis.

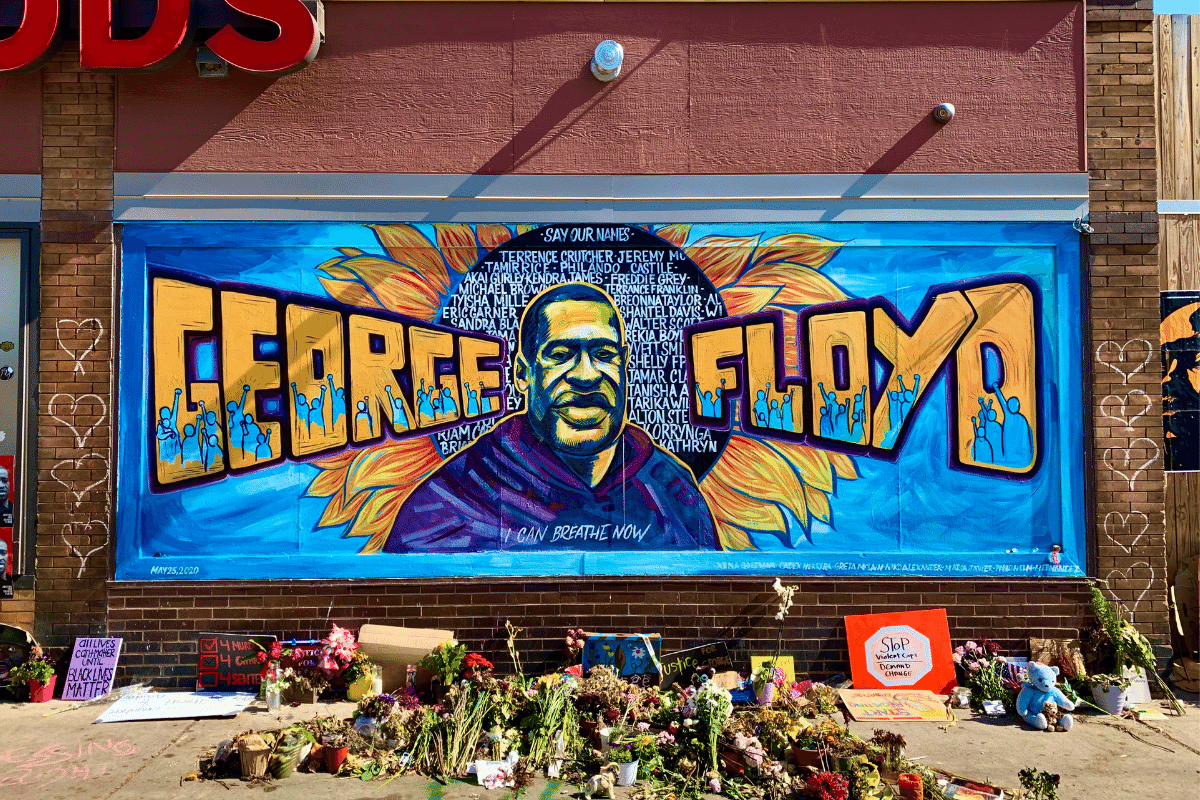

An exaggerated sense of race-based pride is birthed in the absence of a strong centre, and nourishes itself on the ego of restless young men. I began to build my own ideological world, and connected with other like-minded people who were playing the same game, feeding the same psychological appetites. Over time, it turned from a defence against the real racism of others, into a socially-accepted program of aggressive anti-white rhetoric, which continues to be encouraged, or at least willfully ignored, by the liberal mainstream and by many of my white friends.

When I got older, I moved to Montreal for university where I seized professional opportunities that served to build up my confidence and identity. After that, I taught English in Brazil for several years and picked up Portuguese and Spanish. I met people from around the world, which helped me to better situate and understand the unhyphenated aspect of my Canadian identity, and realize how much of it is near and dear to me.

Life became too interesting and complex to continue prosecuting my old ethnic grievances, an exercise that had let me vent my anger but did nothing to abate my sadness. Looking back, I realized that I had been a kid using the few tools I had available to me to conquer childhood foes who were grappling with their own insecurities. It struck me that the key to a deeper, more meaningful and sustainable truth requires that we not get trapped in playing such games at all, and that we make ourselves vulnerable by exposing our true selves to the world.

I’m relating this personal story because I know that many Quillette readers wonder why youth find solace in anti-white social-justice rhetoric, its associated victimhood mentality, and the culture of (now state-sponsored) weaponized sensitivity that this mentality has incubated. My own life shows how this mindset can emerge organically among minorities—whether one is a white Dutch girl in a Muslim neighborhood or a Syrian refugee boy wrapped in a donated oversized parka in the Canadian hinterland.

If you consider yourself a free-speech advocate and classic liberal who abhors identity politics, please think of my story before you launch into your next fusillade. The people to whom you are directing your lectures and barbs usually are in some stage of the cycle I have described regarding my own life. And the feeling of being attacked by the outside world is what made anti-white ethnic pride so attractive to them in the first place.