Top Stories

Reading ‘Lolita’ in the West

The star of Lolita is not Lolita herself, but Humbert Humbert, who hides his obsession with adolescent girls under a mask of tweedy old-world erudition.

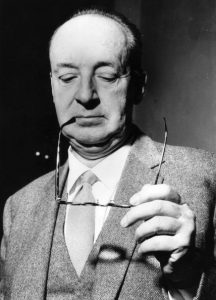

In 1955, when a flushing toilet was still considered too offensive for the eyes of the movie-going public, it’s no surprise that a blackly comic novel about sex with children would cause a stir. Enter Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, the effusively written story of a 37-year-old literature professor who marries a widow in order to gain access to Lolita, her 12-year-old daughter. The star of Lolita is not Lolita herself, but Humbert Humbert, who hides his obsession with adolescent girls under a mask of tweedy old-world erudition. Humbert uses his position as narrator to lecture the reader on the many noble aspects of adult-on-child romance, and to extol his love for his adopted daughter/concubine. To many, Nabokov remains “the guy who wrote that book about pedophilia.”

Following its publication, Lolita was ignored, and then banned. Britain led the way, confiscating all copies of the novel entering the country, and France followed suit. Only months after its release did Lolita receive its first positive review from a respectable paper, the Sunday Times.

Responding to the Sunday Times, John Gordon, editor of the Sunday Express, spoke for Lolita’s moral critics: “Without doubt it is the filthiest book I have ever read. Sheer unrestrained pornography… Anyone who published it or sold it here would certainly go to prison. I am sure the Sunday Times would approve, even though it abhors censorship as much as I do.”

The first edition of Lolita was printed by Olympia Press, a publishing house where the pornographic bumped elbows with the merely provocative. Nabokov was not the first serious writer to take refuge with the seedy publisher: William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, Samuel Beckett’s Molloy and Robert Kaufman’s exposé Inside Scientology all had their first editions at Olympia. The Olympia imprint, however, did little to improve Lolita’s credibility.

In the 2010s, as hand-wringing over the moral effects of art has grown fashionable once more, Lolita has been subjected to fresh scrutiny. In Russia, an ascendant religious Right has sought to discredit Nabokov as an un-Russian cosmopolitan and purveyor of deviance. The Nabokov Museum in St. Petersburg has suffered particular abuse, ranging from graffiti accusing Nabokov of pedophilia to having vodka bottles containing Bible verses thrown through its windows.

One email received by museum director Tatyana Ponomareva, from a group calling itself the “Orthodox Cossacks,” reads: “We believe that Nabokov’s museum cannot exist in St. Petersburg, and ask you to move it outside city limits…. Our goal is to rid our beloved country from the culture of Satan, depravity, and violence.”

These primitive antics have been reinforced by more sophisticated attempts to erode Nabokov’s reputation among educated Russians. In 2013, around the time of the Orthodox Cossacks’ vandalism of the Nabokov Museum, Literaturnaya Gazeta columnist Valery Rokotov enthusiastically set about dismantling Nabokov’s legacy as an icon of Russian culture:

Today, reading Nabokov, you catch yourself thinking that you are wasting your time. You are quickly lulled by the murmur of his text, flowing in a leisurely stream and completely without meaning. You understand fully what stood behind his coronation. His heights of style and loud disrespect of the classics were not only a tool with which to hammer Soviet chiliasm. They turned out to be an ideal stupefying machine, extremely important to the new, postmodern society. It’s no coincidence that postmodernists look on him as a god.

In the West, puritanical concern with art emerges not as much from the Orthodox Right as from the progressive Left. For readers subscribing to the axiom that all speech is an exercise of power, there is little redeeming in a novel that, however prettily written, remains a comedy about rape authored by a wealthy and powerful man. Many revisionist spin-offs of Lolita, like the novel Lo’s Diary and the stage play Dolores, have mounted explicit attacks on the inferred misogyny of the original. Author Rebecca Solnit, who has carried on a years-long feud with Nabokov’s admirers, writes, in an article titled “Men Explain Lolita to Me”:

The popular argument that novels are good because they inculcate empathy assumes that we identify with characters, and no one gets told they’re wrong for identifying with Gilgamesh or even Elizabeth Bennett. It’s just when you identify with Lolita you’re clarifying that this is a book about a white man serially raping a child over a period of years. Should you read Lolita and strenuously avoid noticing that this is the plot and these are the characters? Should the narrative have no relationship to your own experience?

For right-wing critics, Nabokov remains a pervert and an amoral postmodernist; for progressive ones, he’s just another dead white man. The fact that Nabokov snarkily decried anti-war activists and other “class-conscious philistines” has also done little to endear him to social-justice-minded readers. In an article celebrating feminist reappraisals of Nabokov, Boston Globe columnist Alex Beam wrote: “I’m a Lolita fan, but let’s face it, Solnit is right: This is a sprightly little tale about the serial rape of an unwilling or indifferent 12-year-old, embraced and promoted by the male literary establishment.”

* * *

Did Nabokov share Humbert’s inclination toward pedophilia (or, for the pedants, hebephilia)? The notion is popular among readers, and non-readers, of Lolita, and it’s easy to see why. After all, why would Nabokov craft such a charming and witty character, only to fill his mouth with eloquent defenses of ideas with which Nabokov himself disagreed? Why spend five years writing a manifesto for something you’re against?

Throughout the novel, Humbert paints attraction to children as a kind of refined aesthetic taste, himself as a victim of fate, and his own victim as a kind of provocateur:

A normal man given a group photograph of school girls or Girl Scouts and asked to point out the comeliest one will not necessarily choose the nymphet among them. You have to be an artist and a madman, a creature of infinite melancholy, with a bubble of hot poison in your loins and a super-voluptuous flame permanently aglow in your subtle spine (oh, how you have to cringe and hide!), in order to discern at once, by ineffable signs — the slightly feline outline of a cheekbone, the slenderness of a downy limb, and other indices which despair and shame and tears of tenderness forbid me to tabulate — the little deadly demon among the wholesome children; she stands unrecognized by them and unconscious herself of her fantastic power.

There are, in fact, many similarities between Nabokov and Humbert, which feed the theory of Humbert as Nabokov’s alter-ego. Both Nabokov and Humbert were European immigrants to the United States, both taught literature and published poems, both were skilled chess players, both disdained Freudianism, and both shared a talent for audacious multilingual wordplay.

A close reader, however, will find numerous cues that Nabokov did not view Humbert as a kindred spirit. While Nabokov was himself an exile from the Soviet Union, Humbert has only disdain for the novel’s handful of Russian émigré characters. Humbert sarcastically refers to a White Russian colonel-turned-cabdriver as “the Tsarist” and “Mr. Taxovich,” and misses no opportunity to draw attention to the colonel’s poor French and corny ancien régime courtesy. That Humbert is a world traveler who, nonetheless, views Nabokov’s own country exclusively through a set of crude clichés, should not be overlooked.

After writing, Nabokov’s chief pleasure was butterfly-hunting. This was no mere hobby — Nabokov spent years working as a lepidopterist at Harvard University and elsewhere, and ornamented gift copies of his books with color sketches of butterflies. On this topic that was so crucial to Nabokov, he and Humbert once more diverge: at one point, Humbert laughably mistakes a cloud of hawk moths for “gray hummingbirds.” It may also be worth noting that Humbert describes himself, twice, as a spider who wishes to catch Lolita in his web — spiders also being natural predators of butterflies. It’s doubtful that Nabokov, for whom butterfly-hunting was a doorway to life’s sublimity, would have written a self-insert as a lepidopterological ignoramus.

Indeed, much of the novel’s dark comedy emanates from Humbert’s absurd use of elevated verbiage to embellish his predatory and self-deceiving actions. In one scene, Lolita develops a fever. Rather than taking her to the doctor, Humbert decides that the time is right for seduction: “I could not resist the exquisite caloricity of unexpected delights — Venus febriculosa — though it was a very languid Lolita that moaned and coughed and shivered in my embrace.” Here, the reader is invited to laugh incredulously at Humbert’s narcissism; to read this passage as a blithe endorsement of raping children while they have the flu is to miss Lolita’s true audacity.

On the other hand, new readers who have been acquainted with Lolita’s hair-raising reputation, but not with the book itself, are often disappointed by how little sex is to be found within its pages. Nabokov’s sex scenes are as allusive, as intricate, and as playful as the rest of his work. In perhaps the novel’s most explicit moment, Humbert dandles Lolita on his lap:

The day before she had collided with the heavy chest in the hall and — “Look, look!” — I gasped — “look at what you’ve done, what you’ve done to yourself, ah, look”; for there was, I swear, a yellowish-violet bruise on her lovely nymphet thigh which my huge hairy hand massaged and slowly enveloped — and because of her very perfunctory underthings, there seemed to be nothing to prevent my muscular thumb from reaching the hot hollow of her groin — just as you might tickle and caress a giggling child — just that — and: “Oh, it’s nothing at all,” she cried with a sudden shrill note in her voice, and she wiggled, and squirmed, and threw her head back, and her teeth rested on her glistening underlip as she half-turned away, and my moaning mouth, gentlemen of the jury, almost reached her bare neck, while I crushed out against her left buttock the last throb of the longest ecstasy man or monster had ever known.

In short, anyone who buys a copy of Lolita as a companion piece to The 120 Days of Sodom is likely to be let down. (A friend once asked me, in somewhat conspiratorial tones, to lend her my copy of Lolita. She returned it two days later, commenting that it “seemed censored.”)

Alfred Appel, who studied under Nabokov at Cornell and later went on to annotate Lolita for McGraw-Hill, recalls the shock of finding his erudite former professor published by Olympia Press:

I was on the Left Bank and I wandered into a dusty, quaint old bookstore… I did a double-, maybe triple-take because there was a book called Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, my professor. And in the matching green Olympia covers, on the left side was a book called Until She Screams and on the right side of the Lolita was a book called The Sexual Life of Robinson Crusoe. So I bought the middle book, Lolita, and took it back to the barracks. Someone wanted to read my dirty book, but couldn’t get through the first sentence and threw it down, said it was “goddamn literature.”

For his part, Nabokov seemed to find Lolita’s confusion with pornography rather funny. In one interview, Nabokov is seen leafing through a bookshelf full of Lolitas, taking a moment to chuckle at a Turkish edition with generic Harlequin-style cover art: “Look at the man and the girl. I’m not sure who is older!”

Nabokov seems not to have considered seriously that readers might so strongly identify him with Humbert. “The double rumble [‘Humbert Humbert’] is, I think, very nasty, very suggestive,” Nabokov told Playboy in 1964. “It is a hateful name for a hateful person.” To the Paris Review, he commented, “Humbert Humbert is a vain and cruel wretch who manages to appear ‘touching.’ That epithet, in its true, tear-iridized sense, can only apply to my poor little girl.”

Perhaps we identify Nabokov most readily with the narrator of Lolita simply because Lolita is the only one of his books we know well. The antihero of the lesser-known novel Despair lectures us on the virtues of Marxism — how many readers suspect Nabokov of being a secret Marxist? Pale Fire’s protagonist rhapsodizes on the shapely rumps and thighs of male youths — does this suggest that Nabokov was a closet case? We all know Humbert Humbert, the prototypical pervert, but few of us are acquainted with Hermann Karlovich, Charles Kinbote or, for that matter, Vladimir Nabokov.

As Nabokov remarked, “Lolita is famous, not I.”