Top Stories

Francis Fukuyama’s Master Concept

As far as “master concepts” go, this one is hard to beat. One worries, however, that it is a little too neat.

Dignity, recognition, esteem, respect, and the resentment that arises when they are not accorded—these are the themes of Francis Fukuyama’s new book. Like many political commentators, he was surprised by the results of two elections in 2016: the victories for Brexit and Donald Trump. To understand them, he sought a “master concept,” something that would explain not only these results, but also the many other political movements of this decade, from the rise of populism around the globe to #MeToo and campus protests in America. In Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, he proposes “identity,” a concept that grows “out of a distinction between one’s true inner self and an outer world of social rules and norms that does not adequately recognize that inner self’s worth or dignity.”

Fukuyama’s book moves adroitly between a history of how this concept emerged to an explanation of how it has caused our present crisis, before concluding with some suggestions for the future of liberal democracies. His framing of our present crisis as one of identity politics—which he understands broadly enough to encompass right-wing as well as left-wing versions, the international scene as well as domestic conflicts—is lucid and insightful.

It is difficult to discuss Fukuyama’s new book, however, without mentioning the book that established his international reputation almost three decades ago: The End of History and the Last Man (1992). Seizing on the title—and for that matter, only its first half—many commentators came to believe that Fukuyama argued history had come to an end with the fall of communism and the supremacy of liberal capitalism as a new world order. According to this misinterpretation, his argument was invalidated by challenges to this order: 9/11, the resurgence of Russia and China, the financial crisis of 2008, and so on.

But as Fukuyama clarifies in the preface to his new book, that was never his claim. Instead, he argued that the end (not the terminus but the goal: the telos in Greek) of political history was the liberal order, not because there would be no challenges to it, nor because it would never be displaced, but because only such an order could minimally satisfy the demand for recognition that was history’s engine. This half of his argument stemmed from Hegel, who saw history as a dialectic, a movement of rival ideas towards a final consummation.

As Fukuyama appropriated Hegel, only a liberal order would satisfy what the Greeks called isothymia (desire for equal respect). Whereas they saw it fulfilled in democratic city-states such as Athens, the Sophists of the classical era knew such an order to be unstable. For they were aware of some exceptional men who chafed under equal treatment, considering themselves to be superior. (Indeed, the Sophists often considered themselves to be such men.) Their ruling passion was megalothymia (the desire for esteem above others), and Nietzsche gave that desire a modern voice. Foreseeing that the liberal order would stifle greatness, turning human beings into cattle, or the Last Man, he foresaw a Superman (Übermensch) who would disrupt equality and create new values—nobler values—for the entire species.

This was the overlooked second half of Fukuyama’s famous title, which spoke to a perennial struggle between equal recognition for everyone, and the disruptive ambitions of men such as we have seen emerge one after the other in recent years: Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Viktor Orbán, Rodrigo Duterte, Jair Bolsonaro. Fukuyama now sees a dangerous resolution of this struggle, populism, whereby men who style themselves superior secure the allegiance of citizens who have felt disrespected. “I actually mentioned Donald Trump in The End of History,” Fukuyama adds in the preface to his new book, “as an example of a fantastically ambitious individual whose desire for recognition had been safely channeled into a business (and later an entertainment) career.” Little did he know, as he himself admits, that with this man, “megalothymia and isothymia thus joined hands.”

With this new book, Fukuyama tells a history of thymos (spiritedness) and its influence on politics. According to Plato, with whom he begins, this is “the part of the soul that craves recognition and dignity” (though he misunderstands Plato’s psychology—as I argue in a separate essay, which readers may find here). From this ancient theory of human nature, he moves swiftly through the modern notion it best explains: “identity.” He begins with Luther’s focus on faith rather than works, an exclusive attention to the inner attitude of the Christian rather than to his outward engagement with the corrupt Church and its extravagant rituals.

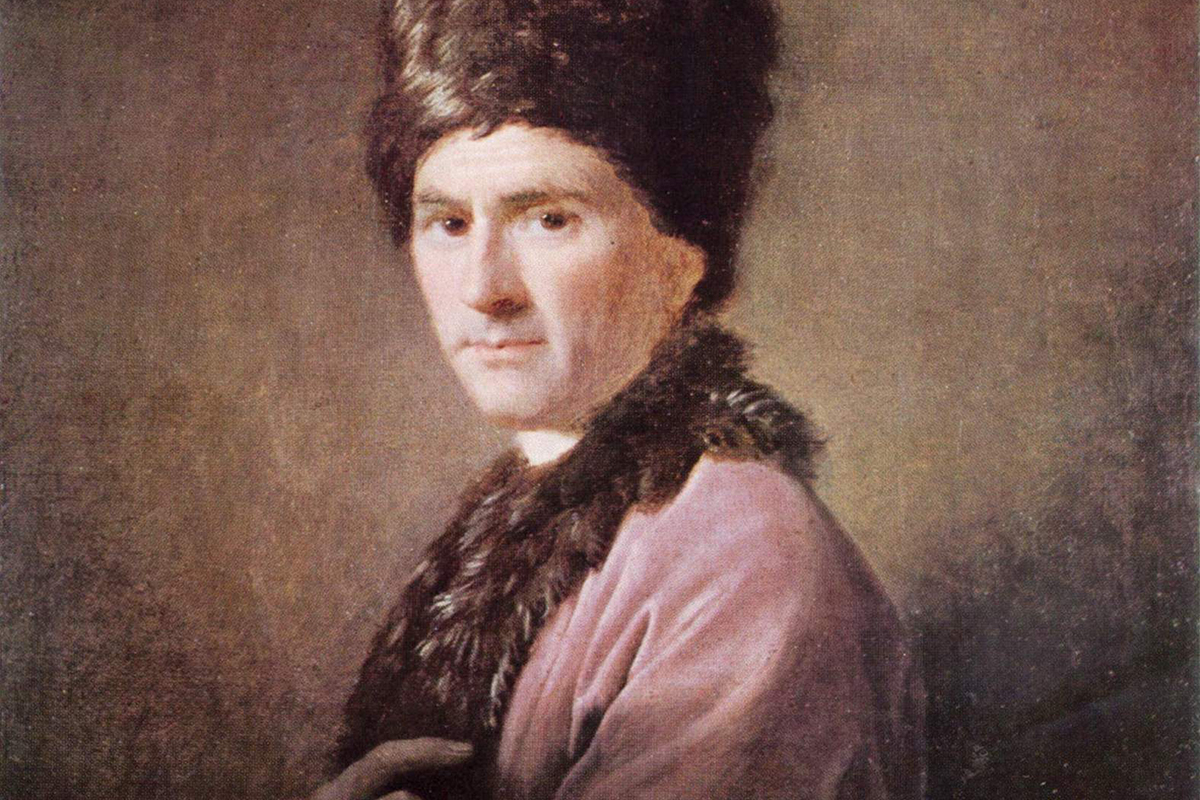

Next, as Fukuyama tells this history, Rousseau secularized Luther’s inwardness and revolt against outward conformity. In some of his writings, he explored his own plenitude of feelings; in others, he cast civilized society as a corrupting influence on the goodness of natural man. Secularizing the Christian belief that every human being has an equal dignity before God, Kant argued that this dignity stemmed from our rational freedom to choose rightly, giving each human being natural rights that every government was bound to respect. Hegel then observed that the French Revolution, carried to the corners of Europe by Napoleon, had inaugurated an era in which governments would now recognize the dignity of everyone, bringing to an end the drama of history, which by his lights was a struggle for recognition.

But not everyone’s identity had become individualized in the manner of the Enlightenment philosophers. Not everyone experienced infinite depths of idiosyncratic feeling, nor did everyone crave to rebel against the conformist group that had raised them. In fact, many felt alienated by the breakdown of longstanding communities as Europe and America industrialized. To avoid this sense of alienation, many clung to the identities of their (rural) upbringing: regional or national culture, or traditional observances of religion.

In the 19th century, then, there was a fork in the development of the concept of identity. For some, it remained individual, while for others it became collective. Governments had to respect the dignity of each citizen, granting all their natural rights as individuals, but the identities of some citizens now also demanded that their collectivities be respected. The stage was set for an era of battles over competing identities.

After World War I, and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the many linguistic and cultural groups mixed together in central Europe and the Balkans demanded rule by separate governments that recognized their unique nationalities. After the next world war, and the slow retreat of the European powers from their colonial ambitions, the many peoples of the Middle East, Africa and Asia demanded the same right. Later, as Islam returned to political potency, those whose identities were primarily religious clashed with those who sought recognition for their nation. In Turkey, the nationalists defeated the Islamists; in Iran, the Islamists defeated the nationalists; in Egypt, the two sides are still in conflict. In every case, though, the demands were for collective recognition.

Meanwhile, in the Western countries, especially the United States, demands for the recognition of individual identities intensified. Women and blacks sought equal recognition with white men as individuals. After World War I, women demanded the vote. After World War II, blacks demanded civil rights. Both were of course successful, though their victories required a fight, especially in the latter case. But after the 1960s, as demands for individual recognition widened to include the rights of homosexuals, indigenous peoples, the disabled, and others, conflicts became clear between these new demands for individual recognition and older demands for recognition of collective identity.

At this point in his story, Fukuyama uses the contemporaneous books of Phillip Rieff and Christopher Lasch to argue that American culture, and eventually American government, took a therapeutic turn. “A liberal society increasingly came to be understood not just as a political order that protected certain individual rights,” he writes, “but rather as one that actively encouraged the full actualization of the inner self.” This is when identity became the universal idiom of politics; individual forms of identity “began to reconverge with the collective and illiberal forms of identity such as nation and religion, since individuals frequently wanted not recognition of their individuality, but recognition of their sameness to other people.”

Conflicts between identities were nonetheless characterized as a contest between left and right, even as each of these two sides minimized the economic commitments that had formerly defined them. The left turned away from the issues of labor and poverty that had been its focus since the 19th century (after the evident failure of Communism, as well as the economic stagnation of the welfare states in the 1970s). It turned instead toward the politics of individual identities, what we now know as “identity-politics.” Thus, for example, the left championed gay rights while the right spoke for religious tradition—including in the debate over gay marriage in the United States, which culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 decision to recognize it as a national right.

During this era of mass immigration, the left has championed the rights of individuals who have sought refuge in the prosperous countries of the West, while the right has opposed the broadening of those rights for nationalist reasons. The left and right have switched roles economically, notice, as it is the poor who have the most to lose, the rich the most to gain, from an influx of cheap labor into Western countries. But this switch is possible because the old (economic) politics of left and right have receded. A new politics of identity finally has come into its own. Nowadays, the politics of recognition—or the politics of resentment wherever identity is not recognized and respected—are everywhere.

Readers of this site need no schooling on the identity-politics of the left, but Fukuyama also illuminates the identity-politics of the right. It diverged from that of the left when it began to champion collective identities over individual ones, but Fukuyama also sees it as to some extent provoked by the identity-politics of the left. Leftists will object: The Men’s Rights Movement has deep roots in the patriarchy, just as American white nationalism has deep roots in the racism and slavery of American history. In short, how could left-wing identity-politics have provoked right-wing versions that precede them?

Against this objection, Fukuyama would argue that those closest to the mainstream are not saying (in the manner of John C. Calhoun) that whites are superior to other races and thus deserve to enslave them. Instead, these conservatives are claiming that their white, European identity has been ignored and disrespected by the elites (in media, academia, and politics) while other identities have been recognized and celebrated by that same elite. The roots, stem, and leaves of white nationalism are in the Confederacy, Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow south, but its sickly flower has indeed been pollinated by left-wing identity-politics.

So identity politics now animates the right as well as the left in America. It also explains the international scene in the way any candidate for a “master concept” must. Putin, for instance, appeals to a widespread sense that the West has not respected Russia’s historic dignity. By associating various symbols with this aggrieved identity (e.g., the Russian Orthodox Church) and demonizing various scapegoats as threats to it (e.g., gays), Putin permits Russians who may be suffering in any number of ways (e.g., poverty) to feel that they are nonetheless owed respect as citizens of a great nation.

Substitute Erdoğan, Orbán, Duterte and Bolsonaro for Putin, make appropriate adjustments to account for the symbols evoked by these leaders to suit their national cultures, and you have plausible explanations for the populist authoritarianism of Turkey, Hungary, the Philippines and Brazil respectively. In each case, a man of cartoonish arrogance and machismo speaks to the wounded pride of people and assures them he alone can make their country great again. The appeal of Law and Order in Poland, the Freedom Party in Austria, the AdF in Germany, the National Front in France, and the other nationalist parties in the European Union can be explained in the same way.

So, too, can the appeal of political Islam across the Muslim world, or for that matter the appeal of Islamic terrorism to young Muslim men in the Western world. Citing the work of Oliver Roy, Fukuyama notes that most of the terrorists who have become radicalized were beforehand no more political than they were poor. “Neither these issues nor any kind of religiosity drove them,” concludes Fukuyama, “so much as the need for a clear identity, meaning and a sense of pride.” This need began to burn when “they realized that they had an inner, unrecognized self that the outside world was trying to suppress.” Although they quote the Koran, then, they are really expressing Luther’s Christian inward turn, Rousseau’s Romantic critique of social corruption, Kant’s rationalist argument for universal human dignity, and Hegel’s historical prophecy about the need for universal recognition.

Fukuyama’s master concept of identity also renders intelligible the surprising elections that gave Americans Trump and the British Brexit. Upon his analysis, neither result is surprising at all. Whatever advantages in economics or foreign relations might have been achieved by the widely expected results, whatever advances in the individualistic identity-politics that now defines the left would have been accomplished by a victory for the Democrats in the United States, neither Remain nor Clinton would have yielded the nationalist or religious recognition of collective identity, the promise of renewed greatness, that large portions of the population now crave.

* * *

As far as “master concepts” go, this one is hard to beat. One worries, however, that it is a little too neat. After all, couldn’t an identity-politics explanation be given for a Hillary Clinton victory had she won? (By the popular vote alone, she did, of course.) Imagine Clinton had won, Britain remained, the other populist authoritarians lost their most recent elections, and so on. Would Fukuyama’s thesis be falsified? No, but that is not the flaw it might at first blush seem to be. His thesis, after all, does not say which variety of identity-politics must win, but only that the winning strategy is one of identity-politics of one sort or another. Whether a country leans left or right economically, whether it favors more authoritarian or more libertarian government—these will be matters of circumstance. What is becoming universal, according to Fukuyama, is how these rivalries are framed: as contests over identity.

What would falsify the thesis would be a renewed, persistent, and ultimately victorious focus by the left and right on economics. If Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn were to win national elections, if the Republican party were to expel Trump and return to its agenda of free trade and Reaganomics, then Fukuyama’s thesis would be in trouble. Neither seems likely as of this writing.

But if Fukuyama is right, and it’s all about identity now, why now? Why have so many people, in so many regions of the world, clamored for recognition nearly all at once? Fukuyama considers, and to some extent accepts, the analysis of Serbian-American economist Branko Milanovic, that the entry of developing countries into the world economy has cost the middle classes of the developed nations the growth in incomes to which they had become accustomed after World War II. The financial crisis of 2008, and the Great Recession that followed, also weakened everyone’s confidence in governments as managers of modern economies.

Ultimately, though, Fukuyama’s answer is not economic: It is about pent up forces that eventually were going to assert themselves anyway. In his telling, rather like Hegel’s, this history (the history of the West only, it must be admitted, for China and India make limited appearances) has an inevitable momentum. At some time or other, identity-politics had to eclipse alternate ways of framing political discourse. As Fukuyama reconstructs it, we have the (mis)fortune of living through that time.

Fusing Hegel with Plato, he also sees identity-politics as inevitable thanks to a universal craving for recognition within human nature. He is right in this respect, and he chooses the correct theory of our nature (Plato’s) to justify his presumption. But as I mentioned briefly at the beginning, he misunderstands this theory, overlooking the powerful role Plato correctly ascribed to reason in the search for the truly common good, the sort of goal around which people of rival identities could gather. This misunderstanding is important: without allegiance to some truly common good binding citizens together, they are bound to end up in a zero-sum competition for wealth and respect.

In the United States, for example, we await the results of Robert Mueller’s investigation of Trump and his associates. Should Mueller’s indictments lead to the president’s impeachment, as I suspect they will, the resulting bedlam will show how thin is the veneer of procedural justice and how weak is Americans’ desire for a truly common good. What will become clear, if it is not already, is the inability of most citizens to rise above the assumptions of their particular identities. As a result, the United States could face a constitutional crisis more serious than any in living memory.

Despite this, Fukuyama does not think identity politics is bad per se. Universal recognition is the political project of the West and should not be abandoned, only managed in a way that mitigates the danger of polarization. How can this be done? Among other suggestions, Fukuyama recommends a compulsory civilian service, in which Americans could develop a common allegiance to national projects.

But proponents of identity politics would protest predictably. If this civilian service were used to build Trump’s wall, for instance, proponents of leftist identity politics would object conscientiously. By contrast, if it were used for projects associated with the left, proponents of rightist identity politics would be up in arms. And which projects nowadays are not associated with one side or the other in our polarized national discourse? Rather than engendering common allegiance beyond identity politics, such recommendations would only exacerbate the problem.

With a common horizon of value, however, such recommendations could bring the nation together rather than tearing it further apart. Fukuyama began his important book with Plato, but ought to have brought it back to Plato in the end. What we need now, above all, is the truly common good he proposed.