History

60 Years On: Reflections on the Revolution in Cuba

It would be decades before the people fully understood the fraudulence of 1959’s heady idealism, but it was corrupt from the start.

Sixty years ago, as thousands of Cubans celebrated the fall of Fulgencio Batista’s regime, an atmosphere of hype and hatred was also overtaking Havana. Not many people foresaw what was to come, but on January 1, 1959, the Republic of Cuba was murdered. Few tears were shed for her at the time—some were too busy desperately packing their bags, while others were preoccupied with burning cars and smashing storefront windows. The institutions not destroyed by the previous dictatorship were savagely dismembered in the following months and years by the Castro regime. Cuba’s National Congress would never again return to session in the National Capitol building (or anywhere else, for that matter). Christmas, bars and cabaret clubs, independent trade unions, religious schools, private clubs, large and small businesses, any and all vestiges of what was Cuba before communism—all of these were destroyed, expropriated, or otherwise expunged from the lives and minds of the Cuban people.

The Cuban Revolution never disguised its contempt for the greatest symbol of the Republican era: Havana itself. The Havana Hilton hotel was renamed, and the city’s glorious buildings, beautiful parks, grand mansions, statues, theatres, and museums were all deemed too bourgeois and ostentatious by the revolutionaries, products as they were of the hated “capitalists and imperialists” they had just driven from power. All this too was now consigned to oblivion or simply neglected as if it had been complicit in some unimaginable evil. “Bourgeois Havana,” hitherto one of the world’s most socially and culturally rich cities, gradually collapsed. One by one, its buildings fell into ruin and disrepair, and in their place, nothing was built after 1959 that would return the city to its former splendor.

The bourgeois Republic’s glamour had masked its cruelty and inequality, but the Revolution ushered in a violent and grotesque cruelty of its own, as ugly as the Soviet brutalist architecture that now filled the Havana suburbs with hundreds of square housing complexes devoid of elegance and grace. Havana began to resemble a permanent war zone, in which a seemingly unending battle would be waged for the next 60 years and counting between the revolutionary tyrants and the ordinary people who populate the city, and who, generation after generation, give it life.

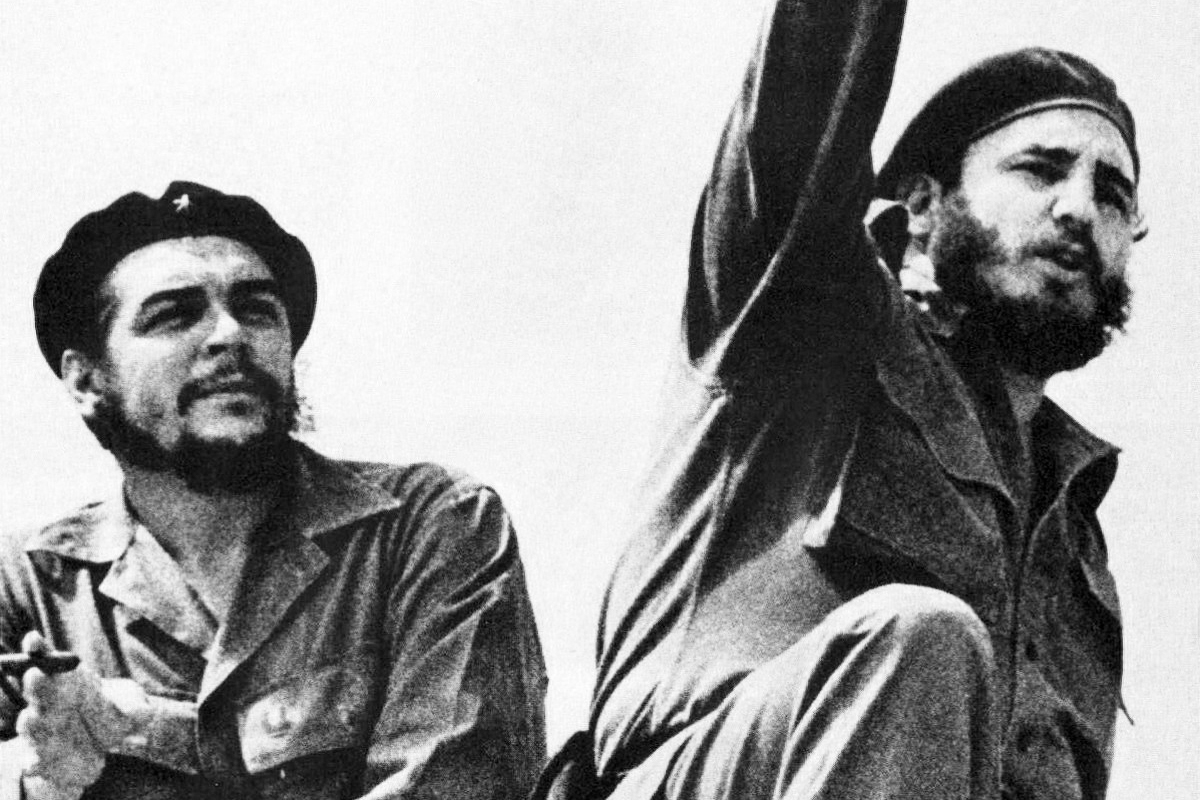

Fidel Castro knew that Cubans in the 1950s would not receive him as some kind of redemptive socialist deity (as North Koreans had done with the Kim dynasty). So, instead, he demanded allegiance to the Revolution itself, the romantic idealism of which masked the pitilessness of the political system that had replaced the Republic Castro despised. “Revolution” meant the liberation of the island and its people from Batista’s dictatorship and battles in the mountains of the Sierra Maestra. It meant “social justice” and the promise of equality for all. It meant the sugarcane harvest, the nation’s newly forged ties to the equally revolutionary Soviet Union and its Communist Party, anti-imperialism, and the cult of Che Guevara. And, in the end, of course, it meant Fidel Castro himself.

If you had a house, ate the State-rationed food, enjoyed access to free healthcare and education, then this was all thanks to the Revolution. And if you suffered or went hungry, or were persecuted and oppressed, if you denounced your “counter-revolutionary” neighbors and relatives to the secret police and pelted political dissidents and homosexuals with eggs, then this too was all for the Revolution. Every time a Cuban referred to the Revolution, instead of the Republic or the government or simply Cuba, he became more than a mere citizen—he became a soldier of revolutionary progress. Uncountable crimes were perpetrated and justified in the name of that single word.

It would be decades before the people fully understood the fraudulence of 1959’s heady idealism, but it was corrupt from the start, when hundreds were sentenced to death by Che Guevara’s revolutionary tribunals and executed in La Cabaña. On August 23, 1968, Castro gave a speech justifying the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the armies of the Warsaw Pact, and in that moment, he effectively surrendered Cuba’s sovereignty and extinguished any remaining pretense of national liberation. Should the same kind of revolt have erupted here, the Soviet Union now had permission to invade the island and restore the revolutionary order by force. From that point onwards, Cuba was no longer free. Once again, the island was condemned to be a docile servant to the new imperialists.

Today, ”Revolution” is a word empty of meaning for most Cubans. People prefer to call the regime “the system,” or “the thing.” Words die when they no longer refer to anything specific, when they are repeatedly used without precision, and when they no longer make any sense to anyone. Young Cubans, hungry for knowledge, modernity, and technology, now prefer to dream of evolution. They blame the revolutionary winds which once intoxicated so many for the devastation of millions of families—those who escaped predestined misery and left loved ones behind, those who were murdered or left to languish in Castro’s jails or forced labor camps, those who perished on rafts or drowned trying to reach the US, and those who remained to suffer the oppressive poverty of a corrupt and brutal dictatorship.

When he replaced his brother as Head of State in 2008, Raul Castro began a slow and insufficient process of reform that nevertheless significantly changed the lives of thousands of Cubans. For the first time since 1959, Cubans were permitted to stay in hotels (a privilege previously reserved for foreign tourists and the revolutionary elites), to apply for a private license to run a small business, to open a restaurant or rent a room, and to buy and sell cars and houses. But following the thaw in diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba, President Obama’s visit to Havana, Trump’s election, and the death of Fidel Castro, the moribund regime found itself more politically vulnerable than ever. Fearing that liberalization would awaken young Cubans and destroy the private kingdom the Castro family had built on the country’s ruins, the regime’s repression of dissidents, artists, and journalists exponentially increased. The arrival of the internet was delayed to prepare the conditions for online censorship and control over fledgling private initiatives was tightened. The system is once again being transformed from within in a desperate attempt to prevent the Revolution consuming itself. At the end of last year, the National Assembly approved new constitutional reforms intended to safeguard the Castro legacy for the revolutionary dynasty’s descendants.

Castro is right to worry. A new generation of Cubans, naturally immunized against ideological doctrine and yearning for the prosperity and liberty their parents were denied, is looking beyond the regime. No evil is eternal, and Cuba’s youth are more connected with the world outside than ever before. But, for the time being, there is not much “social justice” to celebrate in Cuba. An economic abyss still separates the regime’s leaders from average workers earning less than 30 dollars a month. The new rich bourgeoisie are no longer big businessmen, capitalists, and entrepreneurs, they are the relatives of important military personnel and members of the Communist Party who still control the most luxurious hotels, restaurants, and bars on the island. Almost nothing remains of the Revolution’s promises of opportunities and civil liberties for all, for which so much blood was spilled. On the contrary, a strict system of surveillance and control has been its most durable “achievement.” For Cubans, the promise of liberation remains a dream, endlessly deferred.