Art and Culture

Aristophanes’ Orphans: A Disabled Trans Woman Surveys the Grey Zone Between Love and Fetish

Everyone found themselves feeling empty and longing for their other half, be it the woman you were attached to or the man you were attached to.

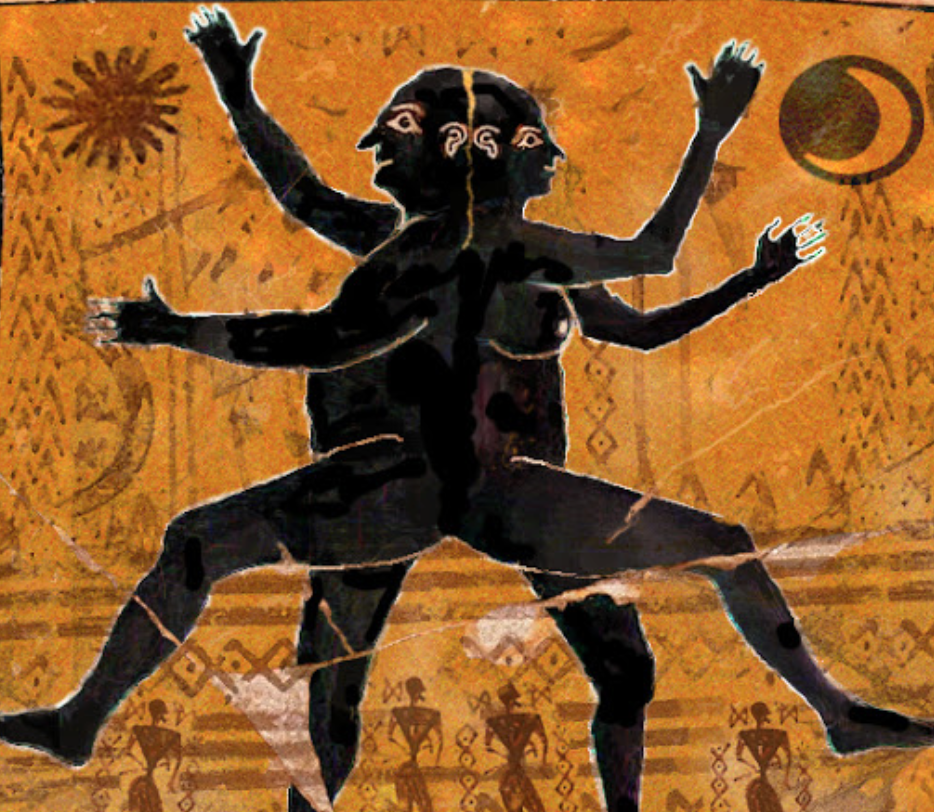

Since I first read Plato’s Symposium, I have been fond of Aristophanes’ account of the origin of love. The tale goes something like this. Human beings used to be spherical creatures with four legs, four arms, and two faces divided evenly between each side. We also used to come in three distinct varieties. Men were those composed of two male halves, women were those composed of two female halves, and the androgynous were those composed of both a male and a female half.

Everything was going swell for us, you might say, until the gods meddled, as they were wont to do. Fearing the power of humanity, Zeus sliced every human into two and had Apollo sew up the opening, with our belly buttons serving as a reminder not to test the power of the gods. Everyone found themselves feeling empty and longing for their other half, be it the woman you were attached to or the man you were attached to. Love was born out of the search to be whole.

I’m fond of this narrative for its simple beauty. But it is sadly incomplete. As progressives are quick to note, sexual attraction is more complicated than the pairings of men and women. People come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. And some categories of human are so peculiar that they can confound the very notion of healthy sexual attraction. In such cases, we sometimes use the term “fetish” to suggest that there is something odd, or even unwholesome, at play.

Perhaps a female object of desire is afflicted with obesity, a health problem now affecting hundreds of millions of people all over the world. Suppose as well that her suitor is attracted because he is, as one might say on dating sites, “all about the bass.” To put it simply, he likes big girls. We could explain this situation politely by saying that there is no such thing as objective beauty in the first place, and so everything boils down to subjective desire. But such aesthetic relativism defies our day to day experience. Moreover, if we consider everything to be beautiful and desirable in some sense, we are left with no language to explain the fact that many people truly do feel ugly and undesirable. The concept of beauty, like every other, contains its own opposite. And if we pretend to disavow any understanding of that opposite, we can never give ourselves license to extol that which we truly find beautiful.

In categories of subjective attraction—again, fetish is the reductionist term—we find the possibility of society’s judgement. In extreme cases, the applied clinical term is paraphilia—“a condition characterized by abnormal sexual desires.” Now imagine what it’s like to the object of this kind of desire. Possessing the sort of body that attracts the interest of only those harboring “abnormal sexual desires” is hardly uplifting. It is not something that we often talk about. But for people living outside of the norms of conventional sexual attraction, it is an existential problem we live with every day.

That includes me. I was born with a genetic disorder called Spinal Muscular Atrophy, a rare condition that results in progressive muscle wasting similar to what is symptomatic in various forms of Muscular Dystrophy. I was never able to walk, and required the use of a wheelchair from the age of three. Although I had good use of my arms throughout my youth, my left arm began weakening in my teenage years and my right arm began to follow in my 20s. Now, I can’t move my arms or hands (or any other part of my body) independently. My joints and hands suffer from contractures, and in some cases have contorted into aesthetically unpleasing shapes. My lower spine suffers from scoliosis, because a corrective surgery in my youth had to be stopped short of completion when doctors became concerned that I might not survive the operation. I have had trouble maintaining weight, and for most of my adult life, I have appeared at least somewhat emaciated.

I am at a slightly healthier weight now thanks to the recent installation of a G-tube, a device drilled through a hole in my abdomen that allows for the direct delivery of nutrients, but also tends to leak a gross substance because, well, because it is a hole in my abdomen. And now that I am eating by mouth far less frequently, my swallowing muscles have become relaxed, and I drool if I’m not paying special attention to the saliva in my mouth. I’ve given up on sleeping without waking up with my face in a puddle.

Now, tell me: Does this sound like a body you want to wake up next to in the morning? It certainly doesn’t sound appealing to me, and I’m the one living in it. But I’m in luck, if that’s the right word, because there’s a whole community of individuals out there specifically attracted to physical disabilities. We call them “devotees,” and for some members of this crowd, everything I listed above would be a positive turn-on.

Our friends the Victorians, still prevalent in today’s psychiatric community, are quick to label this form of attraction as a sort of mental-health condition—a paraphilia. And despite my knee-jerk impulse to reject anything that smells of prudishness, I can’t help but feel that they are mostly right. I do think there is something peculiar and abnormal about specifically desiring someone’s disability. Nothing about their attraction validates my personhood the way personhood is meant to be validated. Rather, it feels like a perversion of my personhood, a privileging of qualities I actively work to transcend in my day-to-day existence.

Still, it is absolutely soul-killing to know that my disability is the primary reason I am single. I have a reasonably pretty face. And as long as I keep the camera focused on my shoulders and head, I can take a decent selfie for purposes of dating sites. I have no problem attracting male attention—because, as many other women can attest, the average guy will message without reading the profile. Unfortunately, that attention always fades when the reality of my disability is made clear.

Truthfully, I understand their reasoning. Even looking beyond aesthetic factors, dating someone who is disabled comes with significant baggage. Still, it’s hard to feel happy with yourself when the person you thought you had a connection with tells you that they don’t want to pursue a relationship because you have a lower life expectancy. (Yes, this has actually happened to me on a number of occasions.) Ben Shapiro, someone who I largely respect despite a few disagreements, is fond of saying, “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” This is true, but what do we do when feelings can’t possibly reconcile with facts? I remain a mere half of an Aristophanian human torn apart by the will of the gods, and I can’t help but yearn to be whole.

But wait. I haven’t told you the half of it. I actively avoided seeking relationships earlier in life—a period during which my body was in better shape that it is now—because I was dealing with crippling gender dysphoria. (I finally transitioned between 2015-16. And now you know where Ben Shapiro and I part ways.) What does transsexuality add to this conversation? Quite a lot, I believe: Trans women are well acquainted with men who actively desire the female body with the custom additions of a penis and an Adam’s apple. Pejoratively, we often call them “chasers”—though they tend to prefer terms such as “admirer” or “trans-oriented,” which minimize or deny a paraphilic dimension to their attraction. In many cases, methinks the chaser doth protest too much.

The debate over the intentions or such suitors is lively and ongoing within the trans community. Are such men totally gay or only sort-of-gay? Is it actually a form of deflected heterosexuality? Progressive trans activist Riley Dennis drew a lot of criticism last year (both from conservatives and some progressives) when she posted a video arguing that it was actually transphobic to claim a categorical disinterest in trans bodies.

Where you stand on the topic largely depends on what you think a “trans woman” is. If you believe we are men who have simply altered our bodies because of mental illness (as some conservatives think), you are likely to argue that desiring the trans female body is simply a fetishistic form of homosexuality. By contrast, if you believe, as many progressives do, that trans women are female, full stop—and that any hard-and-fast distinction between us and cisgender women is tantamount to transphobia—you will be inclined to chalk this chaser/admirer behavior up as normal-ish heterosexual behavior. But whichever way you approach the issue, the takeaway is that this conversation is centered around sexual orientation. Indeed, this is the very argument that trans-oriented “chasers” or “admirers” make to distinguish themselves from paraphilic “devotees.” In the most ambitious form of this argument, they will describe themselves as embracing an emerging, transitory, sexual orientation that is neither heterosexual or homosexual.

I don’t have a clear answer on whether such a distinct orientation exists. But I can speak to the significant changes I have put my own body through, and which now serve to plainly distinguish me from a typical (cis) man. I sought out these changes not out of choice, but out of necessity—call it mental illness if you must. But however many distinctions I can draw between my “girl cock” and a “boy cock,” that doesn’t change the fact that it is a penis and not a vagina. And for those of us lucky enough to have “the snip,” I’m happy you have taken steps to create a replica that makes you feel better about yourself and address your dysphoria, but it still isn’t the real thing. So when a person is attracted to me, I do believe they are attracted to a body that is conceptually distinct from a male body, and from a female body. Which is to say: I am, at the very least, open to the possibility of an emergent sexual orientation that allows the attraction I receive as a trans woman to be conceptualized outside of paraphilia.

So why then does it still feel so consistently demeaning to have a gentleman caller (if I may lapse into my own Victorian forms of expression) express enthusiastic desire to “suck me off”? In short, I suppose I feel this way because—notwithstanding my intellectualized claims about orientation—on some emotional level, I still see my transsexuality as being conceptually similar to disability. And so the reason I disdain my suitors is because the offer of sexual gratification comes embedded within a confession of abnormality.

To be a transsexual is to be at constant odds with your body. The more you are able to successfully transition to a gendered presentation that matches your inner experience, the more comfortable you can make yourself with your dysphoria. But except for the few of us who are able to slip entirely into the now-out-of-fashion “stealth” (i.e., pseudo-cis) lifestyle, the dysphoria will always be there to some degree. And any moment you have that reaffirms the divide between sex and gender is going to cause feelings of emotional discordance.

I think I’m fortunate enough to pass very well. But I live in a smaller city and most of the people in my social circles knew me long before my transition. When I’m with a number of my good friends, I don’t feel dysphoric at all because I know they just think of me as one of the girls. With other people, however, I can tell they are largely just putting up a polite act. Perhaps it’s their religion or their politics, which are at odds with the very existence of people like me, or perhaps they are just unable to let go of their older conceptions of who I am. Whatever it is, their presence makes me dysphoric. Just as the “chasers” seem too outwardly eager to appreciate my trans identity, these unspoken skeptics seem inwardly eager to reject it.

* * *

When I wrote the original version of this article in 2017, that was as far as I could get. We with atypical bodies need partners who will love them, but that love, tragically, will always make us feel uncomfortable. The best I could come up with last year was the plea, to chasers and devotees, to “try not to be creepy about it.” But I now feel more optimistic about the possibility of non-paraphilic attraction—if only for the fact that I now have more experience being truly appreciated as a woman by friends.

One of those friends recently shared an experience with me that helped me push past my fatalistic outlook. She is a cisgender woman who happens to be overweight, and her size has caused her to grapple with many of the same issues I have herein described. She has had sexual partners who were enthusiastically turned on by her size, and she has had partners who denigrated her on the same basis. She recently got out of a long-term relationship with this latter sort of toxic specimen, and she is seeing someone new. As is always the case with new partners, my friend was very self-conscious about what her new beau would think of her body. But when they finally did the deed, she ultimately felt complete. She wasn’t with someone who hated her body or even fetishized it. She was with someone who was able to see the core of who she was and love the whole. What he ultimately “fetishizes” is not my friend’s body, but her being. Call me a romantic, but what else is this other than love? And why should anyone aspire to anything less?

So maybe Aristophanes left out a few details. Perhaps some people really will find their whole with someone who has an atypical body. It’s not something I can pronounce on with certainty unless, and until, I eventually find my other half. But whether or not I succeed, I continue to believe these are important questions for all humans, of whatever shape and orientation, to think about—because ultimately, there is nothing more distinctly human than the hunger we experience as attraction and the rhapsody we experience as love.